Management of the neurogenic bladder with an incontinent stoma is necessary in situations in which intermittent catheterization via the urethra or a continent stoma is not feasible. Cutaneous ureterostomy, vesicostomy, ileal conduit, and ileovesicostomy have all been used for this purpose. Vesicostomy is most commonly used as a temporizing measure in the pediatric neurogenic population. Both ileal conduit, with or without cystectomy, and ileovesicostomy have contemporary roles in the management of the neurogenic bladder.

The development of an algorithm for the safe management of the neurogenic bladder has been pivotal in the prevention of urinary tract complications, which previously resulted in high morbidity and mortality in the population with this condition. The introduction of intermittent catheterization by Lapides and colleagues in 1971 furnished the cornerstone of the long-term treatment in patients with neurogenic bladder. Next, the discovery by McGuire and colleagues that storage and leak point pressures greater than 40 cm H 2 O were deleterious to the upper tract established a guideline for evaluating the results from urodynamic monitoring and supplied a trigger for management changes in the individual patient. Also, the addition of anticholinergic medical therapy to the treatment armamentarium was an indispensable adjunct to controlling uninhibited detrusor contractions, maintaining storage volumes, and preventing the development of poor compliance. The pathophysiology of the neurogenic bladder and the associated urodynamic findings are detailed in the article by McGuire elsewhere in this issue.

Uncontrolled leakage secondary to severe intrinsic sphincter deficiency, detrusor hyperreflexia, or progressively poor compliance can result in a hygiene problem that is difficult to manage in the incapacitated adult patient with neurogenic bladder. A wet perineum can adversely affect attempts to maintain skin integrity and interfere with the ability to treat and heal decubiti. In an effort to achieve a dry perineum, catheter drainage using urethral or suprapubic catheters has been used. However, long-term experience with catheter drainage has demonstrated a wide range of lower and upper tract complications, including urethral erosion, urethrocutaneous fistula, urinary tract infection, development of poor compliance, bladder and upper tract calculi, hydronephrosis, and increased risk of malignancy.

Catheter drainage: urethral, suprapubic, and condom

In the male patient, the option of external condom drainage exists, assuming that mechanical or functional obstruction is not present at any point from the bladder neck to the urethral meatus. If urethral stricture is present, it must be corrected via urethrotomy or urethroplasty, if necessary. The presence of detrusor sphincter dyssynergia (DSD) has been most commonly treated with either sphincterotomy or urethral stents. Although initially effective, sphincterotomy has been associated with hemorrhage, erectile dysfunction, and the need for retreatment to maintain a low-pressure outlet. Urethral stents have compared favorably with sphincterotomy when evaluated in a randomized fashion, with respect to maintenance of low detrusor leak point pressures and residual volumes. Despite the functional success, patients may suffer from pain and dysreflexia. In addition, technical issues may lead to the need for immediate removal, secondary to misplacement or migration, the necessity for placement of an overlapping stent, or stent encrustation over time. Alternatively, transurethral or transperineal injection of botulinum toxin A has been demonstrated to be effective in reducing bladder storage pressures, residuals, and external sphincter tone. Similar to mechanical methods for counteracting the sphincter, injection also requires serial evaluations and repetitions.

In the female patient, the option of decreasing outlet resistance for low-pressure drainage is not viable because of the lack of an effective collection device. Therefore, in these situations, the use of a urethral catheter often results in a progressively dilated outlet, which eventually is not sufficiently competent to hold a balloon. At that juncture, change to a suprapubic catheter is ineffective because of continued leakage via the irreversibly damaged bladder neck.

Although clean intermittent catheterization is the mainstay of neurogenic bladder management, in patients with poor manual dexterity, mental deficits, or quadriplegia, reliable ancillary support from family or caretakers is required. Often, this support is not available creating the need for options that offer tubeless, low-pressure drainage without the need for intermittent catheterization; the primary contemporary alternatives are vesicostomy, ileal conduit, or ileovesicostomy. In this context, cutaneous ureterostomy is discussed briefly for historical interest.

Cutaneous ureterostomy

Cutaneous ureterostomy was described by Johnston for use in cases of pediatric congenital ureteral or detrusor dysfunction. The ureters were tunneled in an extraperitoneal fashion to the bilateral abdominal or flank stomas or a single stoma, requiring translocation of 1 ureter or ureteroureterostomy. The primary drawbacks of the procedure have been stomal stenosis requiring intubation and pyelonephritis. Contemporary techniques have been introduced to reduce stomal stenosis. Kim and collegues reported on the Toyoda technique, wide spatulation of the ureter combined with skin excision, combined with 4-quadrant fixation of the anterior and posterior rectus sheaths encircling the stoma. With the combined procedure, the resultant catheter-free rate in patients was 90%. However, these patients still experienced high rates of pyelonephritis of 19.4% and 17.4% in the early and late postoperative periods, respectively. Utilization of this technique has been supplanted primarily by the advent of intermittent catheterization and vesicostomy in the pediatric population and endoscopic and percutaneous tube placement in the critically ill or end-stage obstructed patients. However, cutaneous ureterostomy may play a more active role in neurogenic bladder management in developing countries where catheters are less readily available.

Cutaneous ureterostomy

Cutaneous ureterostomy was described by Johnston for use in cases of pediatric congenital ureteral or detrusor dysfunction. The ureters were tunneled in an extraperitoneal fashion to the bilateral abdominal or flank stomas or a single stoma, requiring translocation of 1 ureter or ureteroureterostomy. The primary drawbacks of the procedure have been stomal stenosis requiring intubation and pyelonephritis. Contemporary techniques have been introduced to reduce stomal stenosis. Kim and collegues reported on the Toyoda technique, wide spatulation of the ureter combined with skin excision, combined with 4-quadrant fixation of the anterior and posterior rectus sheaths encircling the stoma. With the combined procedure, the resultant catheter-free rate in patients was 90%. However, these patients still experienced high rates of pyelonephritis of 19.4% and 17.4% in the early and late postoperative periods, respectively. Utilization of this technique has been supplanted primarily by the advent of intermittent catheterization and vesicostomy in the pediatric population and endoscopic and percutaneous tube placement in the critically ill or end-stage obstructed patients. However, cutaneous ureterostomy may play a more active role in neurogenic bladder management in developing countries where catheters are less readily available.

Vesicostomy

Blocksom is credited with the initial description of the formation of a surgical vesicocutaneous fistula in an adult patient as a tubeless alternative to the suprapubic catheter. The technique was further modified by Lapides and colleagues in 1960 with the use of skin and bladder flaps.Vesicostomy has been most effectively used as a form of incontinent diversion in the pediatric neurogenic population. Low-pressure bladder drainage to a diaper is continued until circumstances permit the initiation of intermittent catheterization (urethral or catheterizable channel), with or without augmentation cystoplasty. However, vesicostomy has also been demonstrated to be an effective form of long-term decompression in a subset of patients who do not have the individual ability or social support to comply with the care associated with continence.

Technique

The technique has varied minimally since its initial description. However, the Duckett modification of the Blocksom technique is designed to decrease the occurrence of stomal-related complications, stenosis and prolapse.

A 2-cm midline transverse incision is made midway between the symphysis and lower edge of the umbilicus. A transverse rectus fascia incision exposes the midline of the rectus muscle. A triangular piece of rectus fascia is excised to accommodate a 24F catheter. The bladder is distended to assist in the identification of the detrusor. The perivesical fascia is incised to expose the detrusor. Traction sutures are placed on either side of the planned cystotomy. The dissection is performed extraperitoneally, with the anterior surface of the bladder exposed using traction sutures. Blunt dissection is used to mobilize the bladder further into the incision. The umbilical vessels and urachal remnant are identified and ligated. The urachus and a small portion of the bladder dome are excised. The detrusor is sutured to the fascia circumferentially 1 cm from the lower edge of the cystostomy. The bladder mucosa is everted and sutured to the skin using interrupted sutures.

Duckett emphasizes the proper placement of the stoma to avoid the development of complications. Insufficient mobilization of the bladder surrounding the dome or placement of the stoma too close to the symphysis can lead to prolapse or obstruction, respectively.

Complications

In the absence of an acute obstruction of the stoma caused by an insufficient aperture in the fascia, the remaining complications are long term. Prolapse or stenosis may require surgical revision. In the short term, stenosis can be managed by intermittent catheterization. Bladder calculi must be removed, and stasis corrected if present.

Ileal conduit

History

The ileal conduit was initially described by Seifert in 1935 and popularized by Bricker in 1950. This technique has been the gold standard for urinary diversion in patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer, against which neobladders and catheterizable diversions are compared. Soon after the introduction of the ileal conduit, the procedure was applied to the population with neurogenic bladder as a mechanism for treating incontinence and counteracting the effects of the poorly compliant bladder on the upper tract. In the decades that followed, the larger reported series focused on the use of the conduit in the pediatric population, primarily with spina bifida. This form of management was abandoned because of complications, including progressive renal deterioration (16%–61%), pyocystitis (1%–14%), ureteroileal anastomotic stricture (3%–20%), upper tract calculi (1%–11%), and stomal stenosis (6%–48%). As reported by Elder and colleagues, alteration of the technique to a colonic conduit with an antirefluxing ureteral anastomosis did not change the high level of renal deterioration. Therefore, in the late seventies, management of neurogenic bladder in the pediatric population using the ileal conduit was abandoned in favor of intermittent catheterization and ureteral reimplantation for renal units with reflux. In adult patients, although renal deterioration is a documented long-term complication from ileal conduit diversion, it is less concerning than in the developing pediatric kidney.

Technique

The ileal loop procedure has been essentially unchanged since its introduction, with the exception of a minor modification for the purpose of eliminating complications related to loop redundancy or the stoma. The following is a modified version of the technique from a prior edition of this review series.

A vertical midline incision is performed from the symphysis pubis to the umbilicus. After entering the abdomen, a self-retaining retractor is positioned. The ureters are identified and ligated as distally as possible. Temporarily obstructing the ureter with a tie or clip allows for dilation until it is time for the ureteroileal anastomosis. The ureters are dissected superiorly to the pelvic brim while preserving the adventitia. Starting approximately 15 cm from the ileocecal valve, the distal margin of the proposed ileal segment begins. The length required should be sufficient to span the distance from the stoma site to the sacral promontory. Before deciding on the final limits of the segment, the associated vascular arcades are inspected to ensure that at least 2 vascular arcades are present. Mesenteric windows are formed by dividing the peritoneum, fat, and intervening blood vessels. This division can be performed using mosquito hemostats and ties, a stapler, or the monopolar cautery combined with the LigaSure device (Covidien, Boulder, CO, USA). After manually milking any bowel contents out of the planned segment, the bowel is transected with a 55 mm linear cutter. Bowel continuity is performed using a combination of a 75 mm linear cutter and 60 mm linear stapler or a hand-sewn 2-layer closure. The mesenteric defect is approximated with interrupted 4-0 silk sutures.

The left ureter is passed under the sigmoid colon, superior to the inferior mesenteric artery. Alternatively, the left ureter is brought through the sigmoid colon mesentery. With the proximal end of the loop positioned at the level of the sacral promontory, the ureteroileal anastomosis is performed in a standard end-to-side fashion after ureteral spatulation. Absorbable 4-0 or 5-0 sutures should be used, and suturing may be in an interrupted or running fashion. The remaining step is the formation of the stoma. The plunger of a 10-mL syringe may be used as a guide for the stoma site. The skin followed by subcutaneous tissue and fat is cored out using the monopolar cautery. The fascia is scored in a cruciate manner. Four-quadrant 2-0 absorbable sutures are placed at the points of the fascial incision. The underlying muscle is spread manually, and the peritoneum is punctured through bluntly or scored with the cautery, if necessary. The resulting defect should be sufficient to easily accommodate 2 fingers. A Dennis bowel clamp is passed through the stoma site into the abdomen, and the distal end of the conduit is secured and guided through the abdominal wall. The mesentery should be facing medially. The preplaced fascial sutures are placed through the bowel serosa and tied. The mucosa is everted by suturing from the skin edge, to the serosa at the level of the skin edge, and then to the mucosa and tying with the mucosa folding over the skin border.

Complications: Early and Late

In large series of cystectomy and ileal diversion, the most common short-term complications are ileus, acute pyelonephritis, bowel obstruction, urine leak, and ureteral obstruction. With respect to long-term complications, stomal stenosis, pyelonephritis, metabolic acidosis, and ureteral obstruction are seen most commonly. The primary long-term complications of ileal conduit diversion are centered on stomal/peristomal problems (stomal/peristomal lesions, stomal stenosis, stomal retraction), parastomal hernia, conduit stenosis, and renal deterioration. Overall, complications occur in roughly 60% of patients, and the number of complications increases with the duration of follow-up, making continued surveillance of these patients mandatory.

Complications in the Adult Population with Neurogenic Bladder

Chartier-Kastler and colleagues reported on 33 patients with neurogenic bladder secondary to spinal cord injury or debilitating conditions who underwent ileal conduit with or without cystectomy at a mean follow-up of 48 months. Overall, 12 patients (36%) experienced 18 complications. The early complications were characterized by one incident each of sepsis, acute pyelonephritis, ureteroileal anastomotic leak, pelvic hematoma, and lower extremity thrombophlebitis. In comparison, the most common late complications were pyocystis and pyelonephritis. Of the 19 patients with native bladder, 4 (3 men, 1 woman) experienced pyocystis, resulting in 3 secondary cystectomies. There were no stomal complications reported. In contrast, a series by Singh and colleagues evaluating 93 patients with benign disease (76% neurogenic), at least 2 years after ileal conduit, demonstrated a stomal complication rate of 31%, although most were managed with conservative measures.

Simultaneous Cystectomy

One of the primary decisions to be made when using the ileal conduit for the population with neurogenic bladder is whether cystectomy must be performed at the time of the diversion. The addition of cystectomy adds considerable time and morbidity to the procedure. However, the development of pyocystitis, if not effectively managed conservatively, results in the need for a secondary cystectomy. Chartier-Kastler and colleagues reported that pyocystitis occurred in 21% of patients who did not undergo cystectomy at the time of ileal diversion. Similarly, Singh and colleagues reported that in their series of supravesical diversions, 48 of 93 patients (52%) suffered from pyocystitis and recurrent vesical infections, resulting in the need for 5 delayed cystectomies. Patients who were able to forego cystectomy were managed by scheduled bladder irrigation with solutions containing antimicrobials. In addition, in female patients, creation of an artificial vesicovaginal fistula to allow for drainage of the bladder secretions is an option. Even in consideration of the additional morbidity, for patients who are unable to catheterize or are without social support, serious consideration should be given to concomitant cystectomy.

Ileovesicostomy

The ileovesicostomy combines the bowel harvest and gastrointestinal tract reconstitution techniques of the ileal conduit without requiring cystectomy or dissection of the ureters. The ileal segment functions as a conduit between the native bladder and the skin. The advantages of the general ease of stoma care are gained while maintaining the native ureterovesical junction, therefore eliminating the complications related to the ureteroileal anastomotic stricture. In addition, the ileovesicostomy can be reversed under the appropriate circumstances for patients who regain the ability to perform urethral catheterization.

History

The basis for the current ileovesicostomy technique originates from the canine experiments of Smith and Hinman in 1955. The investigators described anastomosing the ileum to the native bladder. Therefore, the native bladder would serve as a continent reservoir with preferential low-pressure drainage through the ileal conduit instead of the urethra. This technique was based on the hypothesis that the intact bladder neck would remain functional with voiding initiated by the detrusor contraction. However, in humans with neurogenic bladder, the pressure source would be furnished by uninhibited bladder contractions or the intra-abdominal pressure. A similar technique was translated to children with spina bifida by Cordonnier in 1957. The investigator described a case series of 3 patients in whom he connected a peristaltic ileal segment to the bladder, with the distal end attached to the skin.

Patient Selection

The ideal patient for ileovesicostomy is characterized by the following: (1) an inability or unwillingness to perform intermittent catheterization, (2) a hyperreflexic detrusor, and (3) a small-capacity bladder. Patients with hypocontractile or atonic bladders with or without high capacity are at an increased risk for elevated storage volumes, which may predispose them to recurrent urinary tract infections and/or formation of calculi. Although, these patients may be offered the procedure, long-term management must be tailored to prevent related complications.

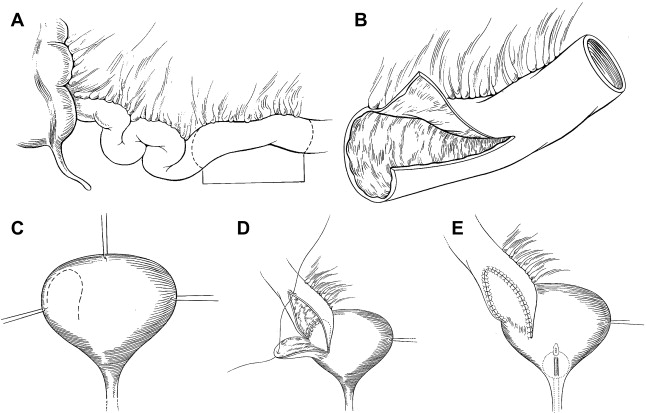

Technique: Open

The contemporary ileovesicostomy technique stems from the description by Schwartz and colleagues in 1994. In subsequent patient series’ by other investigators, there were minor deviations related to the type of bladder incision, such as wide transverse cystostomy in lieu of the U-shaped flap. Regardless of these differences, the surgical principles are based on achieving dependent drainage via a wide ileovesical anastomosis, a judicious selection of conduit length to prevent redundancy, a sufficient aperture in the rectus fascia to prevent future obstruction, and the creation of a stoma conducive to easy appliance fit. The surgical technique as reported by Schwartz and colleagues is depicted in Fig. 1 .

All patients underwent routine mechanical bowel preparation. The proposed stoma site is marked preoperatively with the aid of an enterostomal therapist. With the patient in the supine or extended lithotomy position the peritoneal cavity is entered through a midline or Gibson incision. The bladder and terminal ileum were exposed, and a posteriorly based wide u-shaped flap was created. A suitable segment of ileum measuring 10 to 15 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve is selected taking care that the isolated segment incorporates 1 or 2 distinct vascular arcades. The segment should be just long enough to reach from the bladder to the pre-marked skin site without redundancy; usually 10 to 15 cm are adequate. The ileum is spatulated by making a 4 to 6 cm incision along the antimesenteric border of the proximal portion. The distal segment is brought through the abdominal wall to the predetermined skin site and a nipple is creased. The proximal ileal segment is anastomosed to the bladder starting posteriorly with a single layer of absorbable suture. A 22F multi-hole catheter is placed through the ileal segment into the bladder before the closure of the anastomosis. Standard urethral closure, if required is accomplished via a transvesical or transvaginal approach in female patients, in whom it is done at the internal meatus. In male patients the urethra is closed, when required at the pelvic diaphragm via a perineal approach.