Postoperative Assessment

Responsibility for the immediate postoperative care in the recovery room should be specifically designated to a member of either the surgical or medical team. This person must be familiar with the patient’s preoperative medical history and evaluation as well as details of the source of the donor kidney. Because urine output is an important measure of early graft recovery, it is

necessary to know whether the patient had any preoperative urine output. The assessment should include ensuring hemodynamic and respiratory stability and assessment of volume status. The operative record and early laboratory results should be reviewed, paying particular attention to confirming that immunosuppression was given as ordered. The surgeon should discuss any unusual aspects of the operation with those taking over the patient’s care. Most transplantation programs have a set of standard postoperative orders, and these should be completed. A sample set of orders is shown in

Table 9.1. Institutions vary as to whether they transfer patients from the recovery room to an intensive care unit, a “step-down” unit, or a general ward. Most patients may be safely transferred directly to a general ward, but no matter where the patient goes, it is important that the staff there is experienced in the postoperative care of transplant recipients and familiar with the importance of measuring urine output, establishing volume replacement, and maintaining homodynamic stability. Strict control of blood glucose concentrations in all patients, not only diabetic patients, is important to facilitate recovery of the allograft and to promote healing.

Fluid Replacement

There are probably almost as many protocols for intravenous fluid replacement as there are transplantation programs. The most important aspect is to ensure sufficient fluid replacement to maintain homodynamic stability and urine output, while avoiding making it necessary to dialyze patients who have received more fluid than the new allograft can adequately excrete. Patients are usually admitted for surgery somewhat above their “dry weight” and should be slightly hypervolemic at the end of surgery. If they are dialyzed preoperatively, it is best not to bring them to their dry weight, but to leave them about 1 kg over this. If all the urine passed is replaced, this overhydrated state will persist, and the protocol should allow for this by progressively reducing the volume replaced, provided urine output and blood pressure are adequate. It is useful to separate fluid replacement into “maintenance fluid” and “replacement fluid.” Maintenance is used to replace insensible loss, about 30 mL per hour. This is usually provided as 5% dextrose and water. Urine output and any nasogastric fluid losses are replaced by replacement fluid using half-normal saline because the urine sodium concentration in the early postoperative period is usually 60 to 80 mEq/L. One protocol is to replace all of the initial 200 mL, and then to replace 50% of any volume greater than 200 mL. If the patient is hypovolemic, a greater volume of the urine is replaced, and occasionally if the urine output is low, an additional 500 to 1000 mL of isotonic saline is given as a bolus. Where necessary, potassium, bicarbonate, or calcium replacement should be given in a separate infusion. Potassium replacement should be gradual in oliguric patients, and even some patients with good urine output may not excrete significant amounts of potassium. Serum electrolytes should be ordered at least every 6 hours and more frequently if there are clinical indications to do so such as a very high urine output, or if potassium is being replaced.

Hemodynamic Evaluation

Frequent hemodynamic evaluation is important because an adequate blood pressure and volume status is necessary to establish good graft function. The adequacy of urine output has to be assessed in the context of these two parameters. This may require the use of central venous pressure or a pulmonary pressure or pulmonary wedge pressure measurement. However, for most stable patients, this is not necessary, and a simple regular clinical assessment should be sufficient. Many patients are hypertensive after surgery. This may resolve spontaneously or with adequate pain control, and over-aggressive intervention may lead to the pressure falling too low, increasing the risk for acute tubular necrosis (ATN) and delayed graft function (DGF). In the acute setting, a mildly elevated blood pressure (systolic pressure < 180 mm Hg) is acceptable because blood flow to the newly transplanted organ is dependant on an adequate mean systemic blood pressure. Intravenous hypotensive agents such as labetalol or hydralazine can be used, or if the patient is able to take oral medications, one can use drugs such as clonidine and nifedipine. Unless these are used deliberately to affect calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) concentrations, both diltiazem and verapamil should be avoided because of their potential interactions that increase CNI concentrations.

Assessment and Management of Urine Output

It is a good idea to warn patients before surgery that their urine output after the operation may vary widely. Knowledge of the patient’s pretransplantation urine output is important because those receiving preemptive transplants, and even some dialysis patients, may have daily urine volumes of 1500 to 2000 mL, and this urine from the native kidneys must be accounted for in assessing post-transplantation urine output. In most patients who receive living donor

transplants, urine output is quite high, partly because of their relatively hypervolemic state, and also because of the diuretic effects of an elevated urea nitrogen and of mannitol if this is used intraoperatively. In patients who receive a deceased donor organ, and who had minimal or no urine output before surgery, urine volumes may range from complete anuria, through various degrees of oliguria, to polyuria with very high hourly urine volumes. The use of furosemide, dopamine, or fenoldopam infusions postoperatively is routine practice in some programs, although their benefit has been hard to prove.

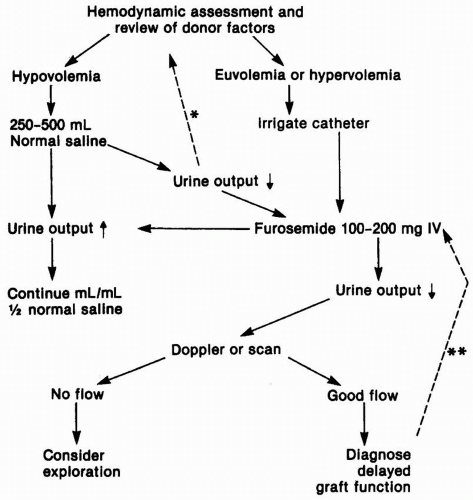

In anuric patients or those with a low urine output, a Doppler ultrasound may be ordered in the in the recovery room to assess the blood supply to the newly transplanted kidney (

Fig. 9.1). The urgency with which the ultrasound is performed depends somewhat on whether oliguria is anticipated. Recipients of a living donor transplant are

always anticipated to have a brisk urine output, and oliguria must be managed in an emergent fashion. If DGF is anticipated, it is reasonable to delay imaging studies. Imaging studies also serve to establish that there is no evidence of ureteric obstruction or a urine leak, although this is usually made obvious by the presence of urine flowing out through the perinephric drain, confirmed by an elevated creatinine concentration in that fluid. The routine use of a double-J stent from the urinary pelvis to the bladder makes ureteric obstruction uncommon. We also recommend an ultrasound for any patient who had a significant preoperative urine output. It is possible that even with the most carefully placed allografts, blood supply may be compromised as the various layers of the incision are closed, and one should not be dissuaded by an overconfident surgical opinion that the blood supply “is fine.” This should be

done concurrently with assessment of volume status and patency of the bladder catheter. If the blood supply is compromised, this is a surgical emergency, and the patient should be returned immediately to the operating room. If the Doppler study is inconclusive, an isotopic study using diethylene pentaacetic acid (DTPA) or a MAG3 renal scan can be used to further define any abnormalities of flow, obstruction, or a urinary leak (see

Chapter 13).

When the urine volume is low, less than 50 mL per hour, or in the presence of anuria, additional initial evaluation includes careful assessment of the patient’s volume status and fluid balance, and confirmation that the bladder catheter is not obstructed, by irrigating it gently to avoid excessive pressure on the newly fashioned ureteric anastomosis. If there are blood clots affecting the patency of the catheter, gentle irrigation may be continued to flush them from the bladder. If this fails, the catheter should be replaced. If the patient appears hypovolemic, a bolus of isotonic saline should be ordered, and when the patient’s volume status is acceptable, or when initial assessment confirmed adequate hydration, a 100- to 200-mg dose of furosemide is given intravenously. If there is no response at this stage, there is little value obtained from repeated doses of diuretic, and the patient should remain on the standard fluid replacement orders. In the rare instance of overzealous fluid replacement, it will be necessary to use dialysis to remove sufficient fluid to correct edema, hypoxia, or congestive heart failure. Here, too, care should be taken to maintain an adequate mean systemic blood pressure at all times, to avoid adding to the degree of ATN.

Postoperative Bleeding

Any combination of the triad of hypotension, a decreasing hematocrit, and pain should raise the suspicion of significant postoperative bleeding. The perinephric drain may fill with blood, or there may be a visible or palpable hematoma. If the hematoma is contained, the buildup of pressure will usually be sufficient to stop further bleeding. If this hematoma appears to be placing pressure on the ureter or vascular bundle, it may be prudent to evacuate it to lessen the risk for ureteric or vascular necrosis. If bleeding continues, and especially if it is not possible to maintain the blood pressure with intravenous fluids or blood replacement, exploration may be required to try to find the source of persistent bleeding. Occasionally, the bleeding is retroperitoneal, and this may be associated with significant pain. In patients with coronary artery disease and in diabetic and older recipients, it is important to maintain a hemoglobin above 10 g/dL.

Postoperative Dialysis

It is usually possible to dialyze patients preoperatively to reduce the requirement for postoperative dialysis. Postoperatively, if the serum potassium concentration is elevated or if the patient is compromised by overhydration, dialysis should be performed to correct this. Except in emergencies, it is possible to use both hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis if the peritoneal dialysis catheter is still in place. Some centers now routinely remove peritoneal dialysis catheters in all living donor transplant recipients and in those deceased donor recipients in whom it is thought that DGF is unlikely to occur. If hemodialysis is used, the blood pressure must be maintained at adequate levels, and no heparin should be used. In the case of peritoneal dialysis, the volumes used for each cycle should be reduced to about 500 mL because larger volumes may be associated with significant pain.