The transformation of the submucosa into a working space provided a paradigm shift for endolumenal endoscopic intervention. The submucosal space can provide an undermining access to the removal of overlying mucosal disease. This space can also provide a protective mucosal barrier accommodating interventions into the deep layers of the gut wall and body cavities, such as the abdomen and mediastinum.

Key points

- •

The submucosa is a loosely attached gut wall layer between the mucosa and muscularis propria.

- •

The histologic uniqueness of the submucosa allows simple mechanical forces such as from fluid instillation or blunt balloon dissection to transform this gut wall layer into a working space.

- •

Submucosal endoscopy is a new concept based on using the submucosa as a working space.

- •

Submucosal endoscopy can be used to perform extensive mucosal excision, removal of subepithelial tumors, per-oral endoscopic myotomy, and potential new applications.

Endolumenal flexible endoscopic excision of precancerous and cancerous mucosal lesions has become an expectation. Removal of lesions up to 2 cm is possible and reliable with cap-based endoscopic mucosal resection. However, removal of larger mucosal lesions poses a challenge requiring piecemeal resection, suboptimal histologic assessment, and a likely need for multiple endoscopic sessions. In the 1990s in the Development Endoscopy Unit (DEU) of the Mayo Clinic, attempts were made to achieve complete resection of large lesions (>2 cm) with en bloc techniques. To facilitate resection of large lesions, reliable submucosal fluid cushions (SFC) were created identifying hydroxypropyl methylcellulose as a readily available, inexpensive injectate equal to hyaluronic acid. Working with the SFC led to an important observation: the mucosa could easily be separated from the underlying submucosa, referred to as “delamination” ( Fig. 1 ). Using a robust and diffuse SFC, wide endoscopic mucosal resection (WEMR) of the esophagus was successful with removal of large areas greater than 5 cm in size involving up to 50% of circumference without inducing severe stricture.

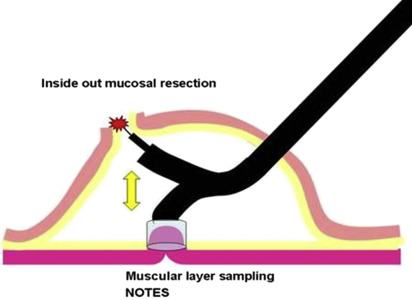

The experience with the development of WEMR directed attention to the submucosa. The submucosa can now be accessed and converted to a working space within which endoscopes and devices can be placed for diagnostic and therapeutic application. Initially, this was not included within the concept of natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). The vision for the submucosa is that within this space further intervention can be performed, “inside” toward the lumen or “outside” toward the deeper layers of gut and even beyond the gut wall ( Fig. 2 ). For removal of mucosal lesions, going inward from submucosa toward mucosa for WEMR was theorized to be safer compared with traditionally going outward from the lumen toward the serosa, with an inherent risk of perforation and bleeding, whether using snare resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). The submucosal space also allows access to the deeper layers of gut wall for diagnostic and therapeutic indications. For example, muscle biopsies from the muscular layers of the gut wall could thus be obtained, which previously required surgery. Offset entry through the mucosa and subsequent exit from the bowel wall at the far end of a submucosal space carries practical appeal for potential NOTES applications.

Technique for creation of the submucosal working space

The submucosal technique that can incorporate the above interventions is performed in a stepwise fashion with major procedural steps: isolating the submucosal layer, mucosal entry, conversion of the submucosal layer into a space, targeted interventions, and mucosal entry closure.

First, the submucosa is isolated by instilling an SFC, gaining access to submucosa. The SFC is important in order to prevent a full-thickness injury to the bowel wall. Historically, this was initially accomplished by forced gas insufflation using carbon dioxide (CO 2 ), but is currently accomplished more easily with liquid solutions, such as saline or hydroxypropyl methylcellulose. Studies have shown improved visualization and ease of performing excision procedures with more robust durable substances compared with saline. Mucosal entry into the submucosa is achieved by a needle knife incision of the mucosa overlying the SFC, sufficiently large enough to accommodate the endoscope. Once submucosal access is gained, the space is created by blunt balloon dissection ( Fig. 3 ). Alternatively, this can be accomplished using traditional needle knife dissection of the submucosa with continual placement of supplemental SFCs to facilitate safe needle knife dissection. In the author’s experience, blunt dissection with small balloons is preferred over the needle knife for several reasons: it is quicker and easier to perform; it is protective of overlying mucosa; and given its atraumatic nature, there is reduced risk of bleeding with this technique. Blunt dissection involves advancement of deflated balloon distally, and inflating the balloon to create a space or in the esophagus, a tunnel, followed by pulling the balloon back to the scope, expanding the space. The scope is then advanced further and the cycle is repeated. Biliary stone retrieval balloons are typically used. Especially designed cylindrical balloons have been used to facilitate submucosal dissection. To facilitate creating the space, a chemical substance, mesna (sodium-2-mercaptoethanesulfonate), can be used. It acts by chemically disrupting the submucosal connective tissue and has been shown to expedite mechanical dissection. After the submucosal space is created, the endoscope itself or endoscopic tools followed by endoscope can be placed into the space. After an intended intervention that does not involve removal of overlying mucosal disease is accomplished, the endoscope is withdrawn from the space and the mucosal entry point is closed. The intact overlying mucosa serves as a protective healing tissue barrier.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree