The evolution of health care in America had its beginnings even before the founding of the nation. This article divides the evolution of American health care into six historical periods: (1) the charitable era, (2) the origins of medical education era, (3) the insurance era, (4) the government era, (5) the managed care era, and (6) the consumerism era.

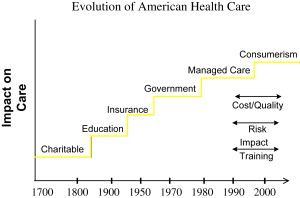

The evolution of health care in America had its beginnings even before the founding of the nation. For the purposes of this article, the evolution of American health care is divided into six historical periods: (1) the charitable era, (2) the origins of medical education era, (3) the insurance era, (4) the government era, (5) the managed care era, and (6) the consumerism era. A summary of the timeframes of these eras appears in Fig. 1 .

The charitable era

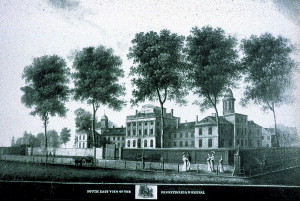

In the precolonial and colonial era there was no organized health care in North America. Hospitals were formed out of public alms houses and care was delivered as a charitable endeavor. After public facilities were begun, religious orders formed hospitals for indigent care. The wealthy could afford to be seen at home. The first hospital founded in this era was the Pennsylvania Hospital, in Philadelphia, in 1752 ( Fig. 2 ). This was followed by New York Hospital in 1791, the Boston Dispensary in 1796, and the Massachusetts General Hospital in 1811. During this period, medical schools began by associating with existing hospitals. Most of the schools were proprietary and to a large extent diploma mills.

The educational era: the origins of American medical education

Medical school education as it is known today was slow to evolve. The medical school of the University of Pennsylvania was founded in 1765, soon followed by King’s College, later to become the College of Physicians and Surgeons, in 1768. Harvard Medical School was started in 1782. For much of the nineteenth century medical school education was poorly regulated and there was no standardized, agreed on curriculum for either undergraduate or postgraduate medical education.

In 1889, the Johns Hopkins Hospital was founded and the influence of Halsted, Osler, and the other Hopkins faculty provided the underpinnings for the modern residency training model. Residency education was based on a full-time faculty staff model with increasing responsibility throughout training and a final year of independence.

As great an influence as Hopkins was on the evolution of postgraduate medical education, the Flexner report of 1910 initiated an even greater change on undergraduate medical school education. In 1904, the American Medical Association created the Council on Medical Education, whose objective was to restructure American medical education. At this time, there was no universal agreement on the requirements for entrance into medical school, nor was there a standardized medical school curriculum. Many medical schools were “proprietary,” owned by one or more doctors, unaffiliated with a university, and run to make a profit. The Council on Medical Education adopted two standards: minimal education requirements for medical school admission, and medical school education should be composed of 2 years of training in human anatomy and physiology followed by 2 years of clinical work in a teaching hospital.

In 1910, Abraham Flexner, a professional educator, was commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation to assess medical school education. Flexner visited all 155 schools in North America and found a wide divergence in their curricula and requirements for admission and graduation. After his extensive study, Flexner made the following recommendations in his report:

- 1.

Medical school admission should require, at a minimum, a high school diploma and at least 2 years of college or university study. Before the Flexner Report, only 16 of the 155 medical schools in the United States and Canada required at least 2 years of university study for admission.

- 2.

The length of medical school education should be 4 years and its content should follow the Council on Medical Education guidelines of 1905.

- 3.

Proprietary medical schools should either close or be incorporated into existing universities.

The impact of the Flexner Report on medical school education and training cannot be overestimated. In 1904, there were 160 medical degree granting institutions with more than 28,0000 students in the United States and Canada. By 1920, there were only 85 institutions with only 13,800 students, and by 1935 there were only 66 medical schools in the United States. Of these 66 surviving medical schools, 57 were part of a university.

It was this revolution in medical school and postgraduate medical education that occurred in the later nineteenth and early twentieth century that laid the foundation for the changes in health care organization and delivery that followed later in the twentieth century.

The educational era: the origins of American medical education

Medical school education as it is known today was slow to evolve. The medical school of the University of Pennsylvania was founded in 1765, soon followed by King’s College, later to become the College of Physicians and Surgeons, in 1768. Harvard Medical School was started in 1782. For much of the nineteenth century medical school education was poorly regulated and there was no standardized, agreed on curriculum for either undergraduate or postgraduate medical education.

In 1889, the Johns Hopkins Hospital was founded and the influence of Halsted, Osler, and the other Hopkins faculty provided the underpinnings for the modern residency training model. Residency education was based on a full-time faculty staff model with increasing responsibility throughout training and a final year of independence.

As great an influence as Hopkins was on the evolution of postgraduate medical education, the Flexner report of 1910 initiated an even greater change on undergraduate medical school education. In 1904, the American Medical Association created the Council on Medical Education, whose objective was to restructure American medical education. At this time, there was no universal agreement on the requirements for entrance into medical school, nor was there a standardized medical school curriculum. Many medical schools were “proprietary,” owned by one or more doctors, unaffiliated with a university, and run to make a profit. The Council on Medical Education adopted two standards: minimal education requirements for medical school admission, and medical school education should be composed of 2 years of training in human anatomy and physiology followed by 2 years of clinical work in a teaching hospital.

In 1910, Abraham Flexner, a professional educator, was commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation to assess medical school education. Flexner visited all 155 schools in North America and found a wide divergence in their curricula and requirements for admission and graduation. After his extensive study, Flexner made the following recommendations in his report:

- 1.

Medical school admission should require, at a minimum, a high school diploma and at least 2 years of college or university study. Before the Flexner Report, only 16 of the 155 medical schools in the United States and Canada required at least 2 years of university study for admission.

- 2.

The length of medical school education should be 4 years and its content should follow the Council on Medical Education guidelines of 1905.

- 3.

Proprietary medical schools should either close or be incorporated into existing universities.

The impact of the Flexner Report on medical school education and training cannot be overestimated. In 1904, there were 160 medical degree granting institutions with more than 28,0000 students in the United States and Canada. By 1920, there were only 85 institutions with only 13,800 students, and by 1935 there were only 66 medical schools in the United States. Of these 66 surviving medical schools, 57 were part of a university.

It was this revolution in medical school and postgraduate medical education that occurred in the later nineteenth and early twentieth century that laid the foundation for the changes in health care organization and delivery that followed later in the twentieth century.

The insurance era

Although insurance has been around for centuries, it was not applied to medical care until the first half of the twentieth century. In 1929, a group of teachers in Dallas, Texas, contracted with Baylor Hospital for medical services in exchange for a monthly fee.

It was Sidney R. Garfield, however, a young surgeon, who really laid the foundation for prepaid health insurance in 1933. Garfield saw thousands of men involved in building the Los Angeles Aqueduct and saw an opportunity to provide health care to those workers. He borrowed money to build Contractors General Hospital near a small town called Desert Center in the middle of the Mohave Desert. Garfield had trouble getting insurance companies to pay the medical expenses of the workers, however, and soon both the hospital and Garfield were running into financial trouble. At that point, Harold Hatch, an insurance agent, approached Garfield with the idea that insurance companies pay a fixed amount per day, per covered worker, up front. For 5 cents per day, workers received this new form of health coverage.

In 1938, the industrialist Henry J. Kaiser and his son, Edgar, were building the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington state and the labor unions were dissatisfied with the fee-for-service care being provided to the 10,000 workers and their families because it was relatively expensive and beyond what many workers could afford. Edgar Kaiser invited Dr. Garfield to form a medical group to provide health care to the workers at a cost of 7 cents per day to be prepaid by the company. This coverage was soon expanded to include the workers’ wives and children. Four years later, during World War II, Henry Kaiser expanded the Garfield model to his wartime shipyards and then to the Kaiser steel mills in Fontana, in Southern California. Kaiser then bought his own hospital in Oakland and the name Permanente was adopted, picked by Henry Kaiser’s first wife, Bess, because of her love of the Permanente Creek that flows year round on the San Francisco peninsula.

Parallel to the genesis of the Kaiser-Permanente system was the development of the early Blue Cross insurance plans. In 1932, the American Hospital Association introduced the first Blue Cross plan that was a prepayment model to hospitals to provide care to enrolled patients. The early Blue Cross plans were nonprofits that received a tax break enabling them to keep premiums low. Blue Shield plans, which were contracted to cover physicians’ services, soon followed.

During World War II, there were strict wage and price controls. Strong unions bargained for better benefit packages, including tax-free, employer-sponsored health insurance. Because employers could not, under law, increase wages, they attracted workers by providing better benefit packages, including health care. This laid the foundation for the rapid expansion of employer-subsidized health care in the post–World War II era.

The government era

The origins of the rationale for government involvement in health care delivery can be traced to the 1940s. In 1943, the Wagner-Murray-Dingell Bill was proposed, which provided for comprehensive health care delivery under the Social Security system; however, the legislation was never approved by Congress. On November 19, 1945, just 7 months after taking office, Truman gave a speech before Congress during which he called for the creation of a national health insurance fund to be administered by the federal government. The fund would be open to all Americans, but would remain optional and participants would pay monthly fees for enrolment.

In part because of Truman’s endorsement of the role of the federal government in medical care, the Hill-Burton Act was passed in 1946. This bill was designed to provide federal grants to improve the infrastructure of the nation’s hospital system. It provided for the construction and improvement of hospital facilities to achieve a goal of 4.5 beds per 1000 people.

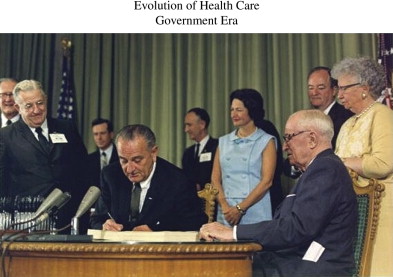

In 1960, Congress passed the Kerr-Mills Act or Medical Assistance for the Aged. This was a means-tested program that contributed federal funds to state-run medical assistance programs for the elderly who could not afford adequate medical care. One major flaw of the program was that five states received 90% of the funds. The Kerr-Mills Act, however, provided the underpinning for the passage of the Medicare and Medicaid laws, which were passed in 1965. President Johnson signed the bill as part of his “Great Society” program and former president Truman was the first enrollee ( Fig. 3 ). Since the inception of Medicare, the number of enrollees has increased from 19 million to 40 million and the expenditures for Medicare have increased faster than any other federal program. It is estimated that by 2030 Medicare will serve 68 million people or one in five Americans and will account for 4.4% of the gross domestic product.

In the 1980s Medicare changed from a cost-based system of payment to hospitals and physicians to a system where payments are predetermined with hospitals receiving a flat rate based on diagnosis. Hospital payments were capitated using diagnostic-related group payments. Hsiao and coworkers with the support of the Health Care Financing Administration introduced the resource-based relative value scale, which determined input by time spent, intensity of work, practice costs, and the costs for advanced training.

Medicaid was also passed in 1965 under Title XIX of the Social Security Act and provided for federal financial assistance to states that operated approved medical assistance plans. Medicaid is a state administered program and each state sets its own guidelines regarding eligibility and services. In 2005, there were 53 million people enrolled in Medicaid and the program cost over $300 billion in federal and state spending. Rosenbaum identified the fundamental reason that Medicaid spending is difficult, if not impossible, to harness when he stated “Federal financing of state Medicaid plans is open-ended. Each participating state is entitled to payments up to a federally approved percentage of state expenditures, and there is no limit on total payments to any state…..With federal contributions limited only by the size of state programs, Medicaid encourages its own growth and expansion.”

In 1993, Clinton became president and a major component of his legislature agenda was the implementation of a national health care program. He appointed his wife, Hillary Rodman Clinton, as the major advocate of its presentation to Congress. It is noteworthy that there was little if any consultation with physicians as to the formulation and planning of what became known as the Clinton Plan.

Despite its introduction with a great deal of publicity, the Clinton Plan never achieved Congressional approval. This was caused by several factors. First, it was not managed well politically and it came to be viewed as a highly partisan rather than a bipartisan initiative. Second, the public appetite for an all-inclusive national health care program was lacking. Although the remainder of the 1990s would witness further modifications in the Medicare and Medicaid programs, there was no emergence of a federally based all inconclusive national health care system. Notable, however, was the 1996 legislation sponsored by Senators Kassebaum and Kennedy, which included a provision for the creation of up to 665,000 medical savings accounts to be available to the self-employed and firms with less than 50 employees.

Concurrent with increased care delivery were the soaring costs of prescription drugs. In 1999, the cost of prescription drugs in the United Stats reached $100 billion, an increase of 16.9%. Total national spending on prescription drugs doubled from 1995 to 2000 and tripled from 1990 to 2000. Americans have demonstrated an increased reliance on drugs, caused in part by the aging of the population and new drug discovery. The average number of retail prescriptions per American per year increased from 8.3 in 1995 to 10.5 in 2000. The increase in the elderly was even more pronounced with the number of prescriptions increasing from 19.6 per individual per year in 1992, to 28.5 in 2000, to 34.4 in 2005, and projected to rise to 38.5 in 2010.

As a political response to this specific component of rising health care costs, Congress passed the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act, also known at the Medicare Modernization Act or Medicare Part D, late in 2003. The passage of this bill was a major legislative initiative of President Bush and the original estimate of the cost was approximately $400 billion over 10 years. Within months of passage, however, the cost estimate was adjusted upward to $534 billion by Medicare chief McClellan. Subsequent analyses have suggested that the true cost of this drug benefit may reach $1.2 trillion.

The past six decades have witnessed legislation that has markedly increased federal participation and government control of health care delivery. The major legislation passed during this period is summarized in Table 1 .