Between 1976 and 1979 the author, the radiologist Rolf Günther and the urologist Gerd Hutschenreiter contributed to the further development of the PNL technique. Initially the radiologist did the puncture, but when ultrasound became available, the whole procedure became urologic. Our first report of a case treated by percutaneous ultrasound lithotripsy [21] was followed by presentations with increasing patient numbers and refinement of the technique at the 1979 annual meeting of the European Intrarenal Surgery Society in Bern and the meeting of the German Urological Society in the same year [22]. Our 1980 presentation at the 75th American Urological Association (AUA) annual meeting in San Francisco was the basis for the manuscript on PNL that was submitted to the Journal of Urology at that AUA meeting. It was accepted with minor modifications. Dr. Scott, who was at that time the editor of the Journal, disliked some concluding remarks in the last three paragraphs of the discussion: “With a set of instruments currently being developed, we expect to reduce the time for the whole procedure to two ambulant sessions for dilation and a one-week hospital stay for stone removal… Percutaneous stone manipulation as a deliberate alternative to open surgery has to compete with the techniques for operative stone removal established over the past 100 years. Its specific place among the various techniques of stone therapy will be defined on the basis of further experience.” We respected his comment “The Journal of Urology is not a medicine man’s paper” by slightly changing these statements, but without changing our ideas [23].

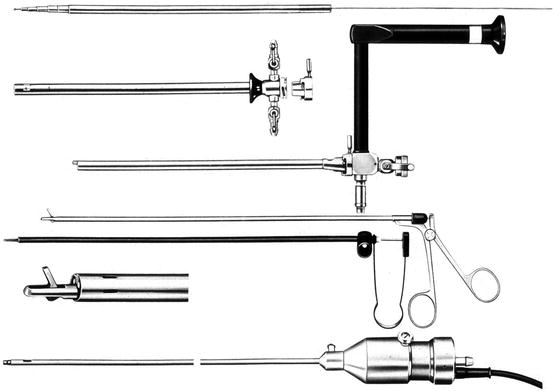

At the time of the presentation at the AUA meeting in May 1980, the telescope dilators designed by the author and produced by Karl Storz were already in use [24]. These dilators were the first instruments purposely built for percutaneous stone removal. They were developed as a consequence of the problems met with serial plastic or metallic dilators initially used and developed as part of a set of instruments (Fig. 2.2) to establish a large, straight nephrostomy tract with minimal bleeding in one session and to allow a complete one session procedure. Percutaneous stone removal in one session is of course desirable for the patient, but it was not easy to achieve. Clayman et al. in their report on 100 cases in 1984 succeeded in only 31 % of their patients [25]. In the authors’ initial series published in 1983, the one-session stone-free rate was also only 60 % [26].

Fig. 2.2

The PNL instruments

Fragmentation of large stones was obtained with an electrohydraulic system [25] or preferably with an ultrasound lithotrite, as the latter caused no harm to tissue [27].

2.1.3 Prone or Supine?

The prone position was the classic position described for percutaneous nephrostomy. For many years the author did not use cystoscopy with retrograde ureteral catheterization before the nephrostomy puncture [24]. Thus it was not necessary to turn the patient from the supine-cystoscopy-position to the prone-nephrostomy-position. Bolsters underneath the abdomen were not used because we felt that they pushed the kidney cephalad instead of exposing it. Thus breathing of the patient was unimpeded, and the anesthetists had no problems with control of the patient as they used epidural anesthesia and could communicate with the patient during the whole procedure.

Experience with a supine percutaneous access was gained with patients that required emergency drainage of a kidney that got obstructed after open surgery. It was easy to do but did not change our PNL procedure.

2.2 The Progress

Many others have contributed to the development of percutaneous nephrolithotomy: Clayman and coworkers were the first to describe the use of angioplasty balloon dilatation catheters for tract dilatation as another alternative to the sequential dilatation with plastic dilators in 1983 [28]. This group published an experience with 100 cases in 1984 [25].

The term endourology was coined by Smith et al. in 1979 [29] when they described the possible future application of percutaneous nephrostomy. Nowadays stone therapy is only a minor aspect of this continuously developing field.

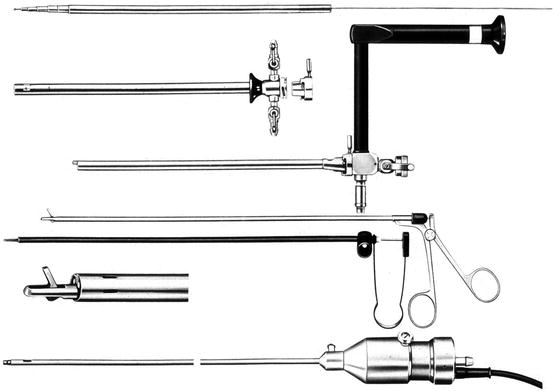

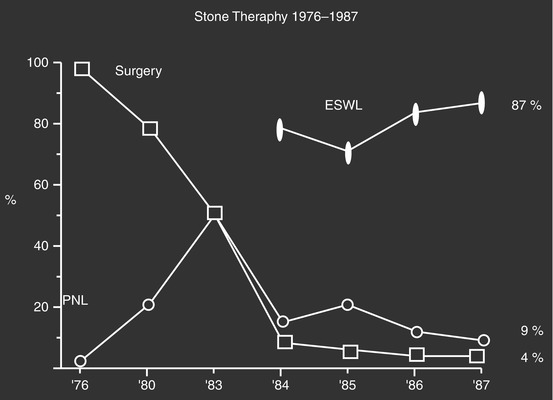

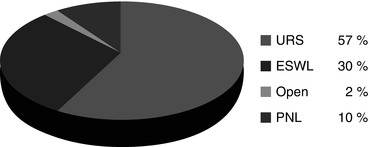

The use of PNL quickly expanded. After personal experience with PNL since 1980, Marberger and collaborators designed a purposely built nephroscope and ultrasound lithotrite for percutaneous use together with the Richard Wolf GmbH, Knittlingen, Germany [30], and Korth with Olympus Winter und Ibe, Hamburg, Germany [31]. Clayman and Castaneda-Zuniga were the first to publish a book on almost every aspect of percutaneous renal surgery [32]. Wickham, who had learned about the technique of PNL during his visits to the Department of Urology at the University of Mainz and the author’s presentation at the meeting of the European Intrarenal Surgery Society in Bern in 1979, was probably the first person to reintroduce a pelvic stone into the kidney to demonstrate the ease of the procedure to the patient and the first to try not to insert a nephrostomy after a percutaneous procedure, as no bleeding from the tract was observed (Wickham, personal communication). But he was also the one who realized the potential of PNL and organized the first world meeting on this topic [33]. One-session PNL was initiated by the design of telescopic dilators [24] which are still very popular after 30 years [34]. Also the Amplatz dilators and sheath became widespread access instruments [35]. Segura and coworkers were the first to publish a series of 1,000 procedures [36]. Many other urologists have contributed to this technique and they, like Clayman and collaborators in 1984 [25], reported in the early 1980s that PNL had replaced 90 % or more of their surgical procedures for renal stone removal. But at that time, minimally invasive PNL was being continuously replaced by a noninvasive technique, namely, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) [37, 38]. The worldwide fourth extracorporeal lithotripter was installed in 1983 at the Department of Urology at Mainz University Clinic in Germany, where the author worked until 1987. ESWL immediately reduced the frequency of PNL to approximately 10 % (Fig. 2.3), because all the small stones that could have been removed by percutaneous extraction were now shocked. Today PNL ranges in this 10 % level in most of the affluent countries, as data from the authors department in Mannheim show (Fig. 2.4). The situation is different in countries where there are still a lot of big stones as in India, as shown by the statistics from Muljibhai Patel Urological Hospital, India (Fig. 2.5). With the enormously high PNL working load in his country and several thousands of cases having been treated in his department, Dr. Desai has somehow reinvented PNL [39, 40] and has of course already a positive experience with the supine position [41].

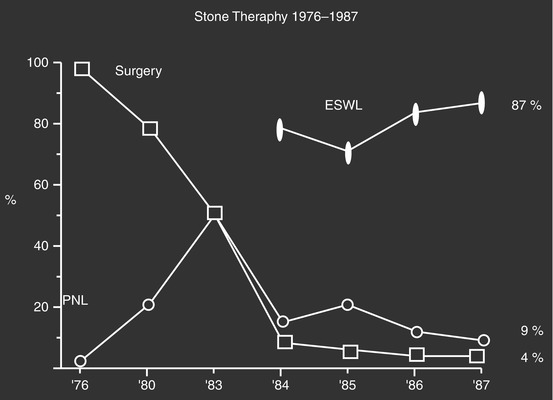

Fig. 2.3

Frequency of stone therapy from 1976 to 1987 in the Department of Urology, University Clinic, Mainz, Germany

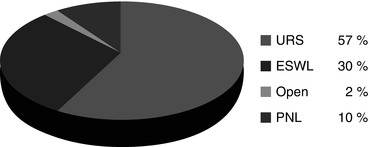

Fig. 2.4

Frequency of stone therapy from 2007 to 2008 in the Department of Urology, University Clinic, Mannheim, Germany

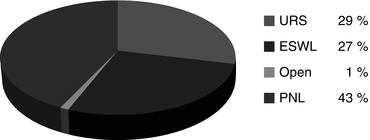

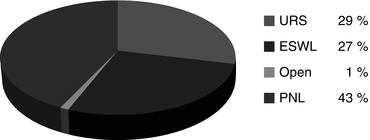

Fig. 2.5

Frequency of stone therapy from 2007 to 2008 in the Muljibhai Patel Urological Hospital, Nadiad Gujarat, India (courtesy of Dr. Mahesh Desai)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree