Technique and Endoscopic Anatomy of Nasal Cavity and Hypopharynx

Introduction

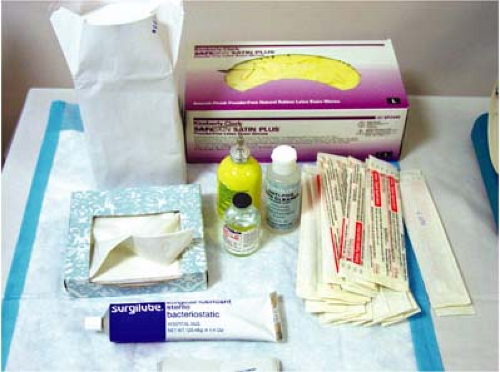

Transnasal esophagoscopy (TNE) is performed by placing a small-caliber, flexible endoscope via the nose into the hypopharynx and then into the esophagus. TNE is performed with the patient awake, sitting upright in a chair. No conscious, or intravenous, sedation is used (1,2,3,4 and 5). The key to successful performance of TNE is adequate topical anesthesia and vasoconstriction in the nasal cavity (Fig. 2.1). Before the technique of TNE is addressed in detail, a review of basic endoscopic anatomy of the nasal cavity and hypopharynx will be given. Examples of common nasal and hypopharyngeal pathology will be shown to familiarize the endoscopist with several variations of the endoscopic anatomy that may be encountered as the esophagoscope is passed from the nostril into the esophagus.

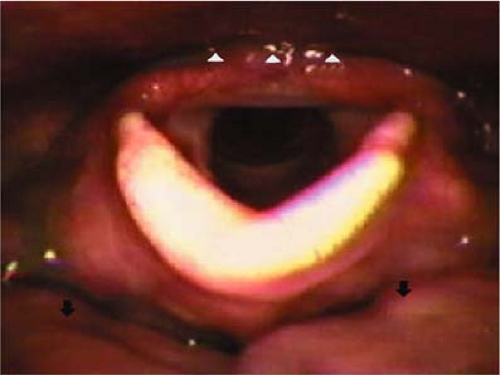

In contrast with transoral esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), the image orientation on the video monitor is such that the tongue base is at the superior portion of the monitor (i.e., at 12 o’clock), and the esophageal inlet is located inferior to the tongue base. During TNE, the tongue base and esophageal inlet are consistently in the anatomic position familiar to most otolaryngologists, with the base of tongue located at the inferior portion of the monitor (i.e., at 6 o’clock) with the esophageal inlet superior to the tongue base and “behind” the arytenoid cartilages (i.e., at 12 o’clock) (Fig. 2.2).

Nasal Anatomy

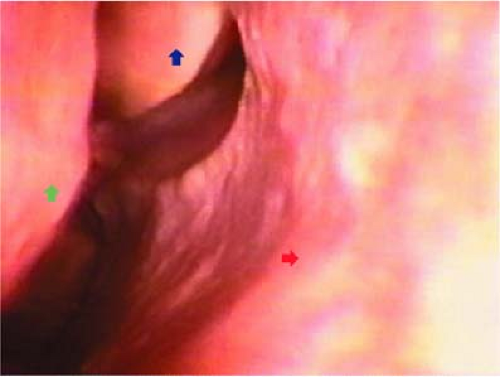

The TNE scope should be placed in the side of the nasal cavity that is most patent. Therefore, a nasal examination is performed prior to TNE to determine the less obstructed side. Three primary structures in the nose have to be visualized to ensure safe, unobstructed passage: the nasal septum and the inferior and middle turbinates (Fig. 2.3). There are two ways of passing

the scope through the nose. One is to pass the scope between the middle and inferior turbinates, and the other option is to pass the scope along the floor of the nose, usually inferior and medial to the inferior turbinate. The majority of the time, the authors prefer the latter route.

the scope through the nose. One is to pass the scope between the middle and inferior turbinates, and the other option is to pass the scope along the floor of the nose, usually inferior and medial to the inferior turbinate. The majority of the time, the authors prefer the latter route.

Figure 2.4 Endoscopic view of a right nasal cavity. Note that the deviated nasal septum (red arrows) is touching the inferior turbinate (blue arrowheads), causing near complete nasal obstruction. |

Figure 2.5 Endoscopic view of a nasal septal perforation. View is from the left nasal cavity; the right middle turbinate (blue arrowheads) is seen through the septal perforation (red arrowheads). |

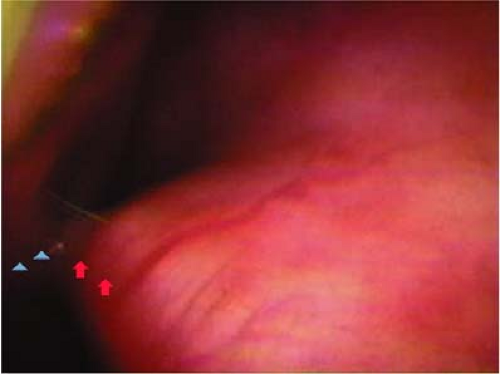

Certain variations in normal anatomy may make transnasal passage of the scope difficult. Nasal septal deviations are a very common cause of unilateral nasal obstruction (Fig. 2.4). Generally, if one side of the nose has a markedly deviated septum, the other side is more patent and will allow easier passage of the endoscope. Another relatively common variation, and one that can be confusing to the endoscopist, is a nasal septal perforation (Fig. 2.5). Care must be

taken not to inadvertently traverse or traumatize the opening in the perforated septum as such a maneuver will likely make it difficult to readily advance the scope, as well as possibly causing septal trauma and epistaxis. Another common pathological condition of the nasal cavity are nasal polyps, which can cause significant nasal obstruction (Fig. 2.6). When nasal polyps are seen, it is preferable to pass the scope on the side where the polyps are smallest. If the endoscope cannot be passed through either nostril, then a standard gastrointestinal oral endoscopy appliance can be used to pass the scope transorally (Fig. 2.7). More topical anesthesia on the tongue base is needed to perform unsedated per-oral esophagoscopy.

taken not to inadvertently traverse or traumatize the opening in the perforated septum as such a maneuver will likely make it difficult to readily advance the scope, as well as possibly causing septal trauma and epistaxis. Another common pathological condition of the nasal cavity are nasal polyps, which can cause significant nasal obstruction (Fig. 2.6). When nasal polyps are seen, it is preferable to pass the scope on the side where the polyps are smallest. If the endoscope cannot be passed through either nostril, then a standard gastrointestinal oral endoscopy appliance can be used to pass the scope transorally (Fig. 2.7). More topical anesthesia on the tongue base is needed to perform unsedated per-oral esophagoscopy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree