Fig. 18.1

(a) Contrast from antegrade approach only; (b) contrast added from combined antegrade and retrograde approaches helps to map the length and severity of a ureteral stenosis

Moreover, a reconstruction of a CT scan in arterial and excretory phases will reveal the presence of a vessel causing a stenosis (Fig. 18.2) or the presence of vessels located posterolaterally to a ureteral pelvic stricture, which is important to know before laser incision.

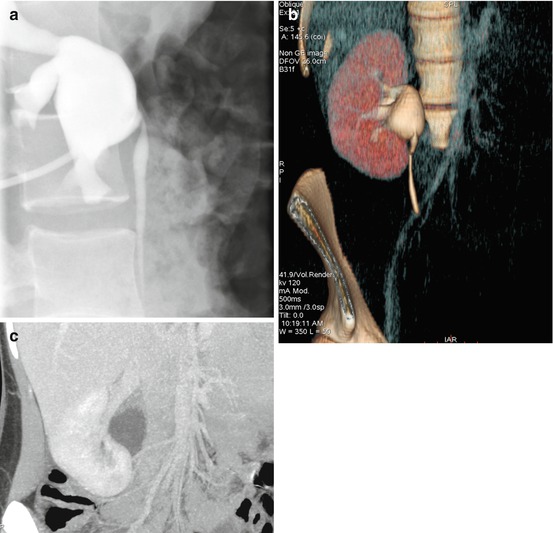

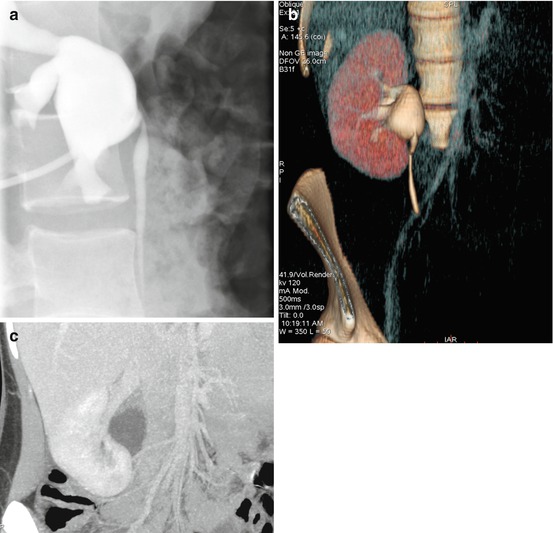

Fig. 18.2

(a) Antegrade pyelography showing a stenosis of the UPJ. However, the underlying cause is not clear. (b) 3D-CT scan, excretory phase, again illustrating UPJ obstruction. (c) CT artery phase visualizes a polar artery. By putting figure (b) and (c) together, it is clear that the stenosis is caused by a polar artery

18.1.2 Transitional Cell Cancer (TCC) in the Upper Urinary Tract (UUT)

The preoperative planning of the percutaneous access route is of utmost importance. The chosen calyx should give access to the calyces needed or to the ureter. Moreover, in case of TCC of the renal pelvis, it is crucial not to puncture through the tumour. The access should always be placed through a calyx containing no tumour.

A computerized tomography with three-dimensional reconstruction (3D-CT) is a good tool for a thorough preoperative planning. Even though some tumours will not be revealed by CT (see also Chap. 5), this is probably the best radiographic method to map out the UUT-TCC. By rotating 3D images in different directions, one can get a good idea on accessibility through a punctured calyx to other calyces and to the ureter.

18.2 Preparation and Positioning of the Patient

Ureterorenoscopy (retrograde, antegrade and combined approach) can be performed under general or spinal anaesthesia. General anaesthesia has the advantage of the patient being spared of the discomfort that may occur from manipulation and irrigation of the renal pelvis and the possibility to obtain breathing control if needed.

For the possibility of a combined antegrade and retrograde approach, the patient is placed in a supine position. One or two wedge cushions are placed under the flank so that a desired calyx can be punctured or the nephrostomy tube becomes accessible (Fig. 18.3). Placing a nephrostomy tube a few days prior to the percutaneous procedure could be an advantage because bleeding caused by the puncture will not disturb the endoscopic evaluation of renal pelvis and ureter. On the other hand, if the patient has a tumour, an indwelling nephrostomy tube may increase the risk of tumour cell seeding. Irrespective of the timing of the renal puncture (performed at the time of percutaneous surgery or beforehand for the placement of a nephrostomy tube), the choice of the calyx for renal access has to be planned thoroughly.

Fig. 18.3

Positioning on operating table, with wedge cushions under the flank to expose the nephrostomy tube

18.3 Accessing and Investigating the Renal Pelvis and Ureter

When the patient is punctured on the operating table during the percutaneous procedure, a ureteral catheter is placed whenever possible. This will allow to inject contrast and distend the renal pelvis. By using a combination of ultrasound and fluoroscopy guidance, the desired calyx can then be punctured. In case the patient has a suitable nephrostomy tube placed at the tip of a desired calyx, that access can be used.

If access to the renal pelvis is needed for the treatment of a calyceal diverticulum, a large renal pelvic tumour or a UPJ stenosis, it is advisable to dilate the access tract and to place an Amplatz sheath. If the ureter is the target, it is usually not needed to dilate up to 26–30. In those situations, it is handy to use a ureteral access sheath (UAS) or a peel-away sheath. A peel-away sheath has the advantage of being adjustable in length, decreasing the risk of slipping out of the body (Figs. 18.4, and 18.5) as compared to a UAS. A flexible ureteroscope can then be introduced, beside the safety guidewire, through the peel-away sheath (Fig. 18.6).

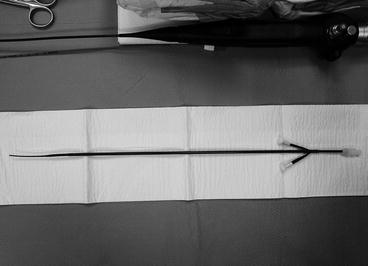

Fig. 18.4

Peel-away sheath

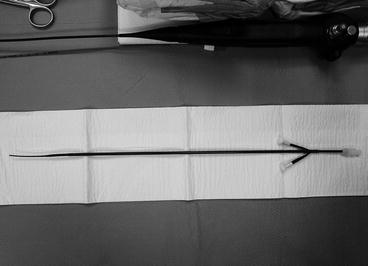

Fig. 18.5

Peel-away sheath with guidewire

Fig. 18.6

Flexible ureteroscope introduced through a peel-away sheath

In case of a ureteral stricture or of a patient with a urinary diversion, a guidewire is placed all the way from the renal pelvis through the urethra or urine reservoir stoma, so that traction can be added through the wire (Figs. 18.7, and 18.8). An additional guidewire is placed using a dual-lumen catheter in order to have both a safety and a working guidewire (Figs. 18.9, and 18.10). A flexible ureteroscope can then be introduced antegradely or retrogradely (Fig. 18.11).