Fig. 3.1

Fusion of prerecorded MRI data with real-time U/S (Urostation®, Keolis): the blue net is an MRI 3-D reconstruction of U/S information collected before the procedure, delineating the whole prostatic gland. The small yellow sphere indicates the suspected lesion to be targeted during biopsy

Technically a prostatic MRI should be multiparametric providing morphological (T1- and T2-weighted) and functional information. Morphological sequences are consistent with axial1 T1-weighted images and three-plane T2-weighted images including axial, coronal and sagittal. Functional information comprises of three phases (Fig. 3.2a–d):

Fig. 3.2

(a–d) MRI prostate showing a cancer (x) developing from the anterior part of the prostate base (Courtesy of S. Novellas, Radiology, Arnault-Tzanck Institute, Saint-Laurent-du-Var and CHU Nice, Nice, France). (a) Is T2-weighted, (b) is a diffusion picture at b1000, (c) is a perfusion phase and (d) shows a type 3 enhancement according to PI-RADS classification. Contrary to adenoma, cancer has an early enhancement and a rapid washout

Perfusion phase: T1-weighted dynamic phase with gadolinium injection

Diffusion phase

Spectroscopy phase (spectro-MRI)

3.4 Primary Diagnosis

This is confirmed by the histopathological examination of the prostate core specimens provided by a TRUS-guided biopsy:

1.

Prior to the prostatic biopsy, a urine culture should always be performed to exclude urinary infection. The recommended pre-procedural antibiotic prophylaxis continues to be second-generation fluoroquinolones, such as Ciprofloxacin (500 mg) which is more effective than ofloxacin (400 mg) [18]. The tablets are best taken 1–2 h before the procedure. Ceftriaxone is an alternative in cases of allergy to fluoroquinolones. There are reports of ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli in the faecal flora [19, 20] which may justify the combination with other antibiotics in some cases, e.g. ertapenem and amikacin [21–23].

Here again the patient’s positioning varies according to teaching institutions, from the lithotomy position (doctor sitting between the legs like for a cystoscopy) to the left lateral position with flexed hips and knees (doctor sitting behind the patient). The former is the preferred position for high-risk patients undergoing the procedure under sedation and close monitoring in operating theatres.

TRUS-guided prostatic biopsy performed under local anaesthesia through a periprostatic infiltration has been proven superior to instillation of intrarectal anaesthetic creams such as 1 % lidocaine solution (Xylocaine® or lignocaine) [24]. Low-dose aspirin is no longer considered an absolute contraindication for prostatic biopsy [8, 25]. Large studies have also suggested that discontinuation of warfarin is not necessary [26, 27] as long as the international normalized ratio (INR) is within the therapeutic range. However, if a history of coagulopathy is discovered, the patient should have his coagulation profile normalized prior to the prostatic biopsy. The recommended points of technique on performing the first biopsy are [28]:

12-core biopsy if there are no clinical or imaging anomalies (i.e. a biopsy indicated only by an abnormal PSA level).

Additional biopsy at the suspected area if there is an abnormality on clinical examination (nodule on DRE) or prostatic images.

One-core biopsy in each lobe may be sufficient when there is clinical suspicion of locally advanced disease (≥T3b, see TNM classification later).

Complications: A retrospective review of nearly 6,000 TRUS-guided biopsies of the prostate performed over 10 years has revealed the following complications [29]:

Minor: haematospermia (36.3 %), haematuria (14.5 %) and rectal bleeding persisting up to 2 days (2.3 %)

Major: bacteraemia with fever requiring admission (0.8 %), persistent rectal bleeding for more than 2 days (0.6 %) and urinary retention (0.2 %)

Interestingly this study did not show increased morbidity when comparing three different protocols with 6, 10 and 15 core biopsies. Vasovagal reaction is also known to occur.

In a recent study the mortality rate within 120 days after prostate biopsy (0.1%) was not found to be higher than in a control group (0.18%), and the deaths were mainly associated with risk factors such as ischemic heart and respiratory diseases [30].

The transperineal prostate biopsy is an alternative to the transrectal route when the anal orifice is closed after previous rectal surgery. It is also a valuable approach for patients with initially negative TRUS-guided biopsies and persistently high PSA or MRI images showing suspicious anteriorly located lesions [31].

2.

The primary histopathological diagnosis of PC should ideally be confirmed by two pathologists. After staining the prostate cores with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E stain), the pathologists will first study the architectural patterns (presence of small glands with haphazard distribution, cribriform, fused and poorly formed glands or solid sheets, cords or isolated cells), the nuclear atypia (increase nucleocytoplasmic ratio with prominent nucleoli) and the prognostic factors like invasive growth and presence of perineural infiltration [32] (Fig. 3.3a–c). Additional immunohistochemical studies are sometimes needed for small tumour foci to identify invasive adenocarcinoma which is characterized by a loss of basal cells and, consequently, negative basal cell markers (34βE12 and p63). Conversely there will be a positive study for alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase (AMACR, also called 504 s) which is upregulated in prostate carcinoma [32] (Fig. 3.4). Nonetheless immunohistochemistry should be reserved only for equivocal cases where conventional pathology is inconclusive [33]. PC histopathological grading was first reported by Gleason [34] and was modified later by the International Society of Urological Pathologists (ISUP) [35] (Table 3.1). The histopathological report must also include the localization and the number of positive cores out of the total number (generally 12), as well as the length of the malignant tissue in millimetres in every positive core. This is reported as a percentage of the total length of the positive cores. Several studies have demonstrated that the total tumour length in biopsy cores is an important prognostic factor. This was even suggested to have a stronger correlation with overall survival than the patient’s age, serum PSA or Gleason score [36]. This factor is taken into account especially when considering a patient for active surveillance (see later).

Fig. 3.3

(a–c) A prostatic core procured through TRUS-guided biopsy (H&E). This was a 3+3 (6) Gleason score, the most common pathological pattern (Courtesy of A. Durlach, Pol Bouin Laboratory, University Hospital of Reims, France)

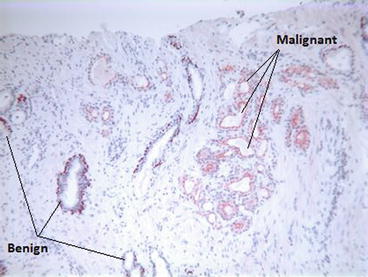

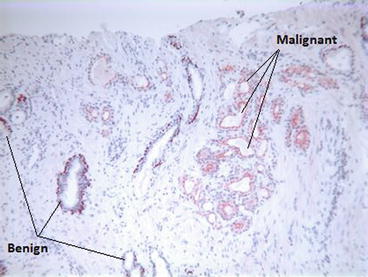

Fig. 3.4

Immunohistochemistry using P63 and racemase: P63 stains the glands in brown and racemase in red. Being P63 negative and racemase positive, carcinomatous glands are stained in red (right of the picture), while the P63-positive and racemase-negative benign glands are stained in brown (left of the picture) (Courtesy of A. Durlach, Pol Bouin Laboratory, University Hospital of Reims, France)

Table 3.1

2005 ISUP modified Gleason system

Pattern 1 | Circumscribed nodule of closely packed but separate, uniform, rounded to oval, medium-sized acini (larger glands than pattern 3) |

Pattern 2 | Like pattern 1, fairly circumscribed, yet at the edge of the tumour nodule, there may be minimal infiltration |

Glands are more loosely arranged and not quite as uniform as Gleason pattern 1 | |

Pattern 3 | Discrete glandular units |

Typically smaller glands than seen in Gleason pattern 1 or 2 | |

Infiltrates in and amongst nonneoplastic prostate acini | |

Marked variation in size and shape | |

Smoothly circumscribed small cribriform nodules of tumour | |

Pattern 4 | Fused microacinar glands |

Ill-defined glands with poorly formed glandular lumina | |

Large cribriform glands | |

Cribriform glands with an irregular border | |

Hypernephromatoid | |

Pattern 5 | Essentially no glandular differentiation, composed of solid sheets, cords or single cells |

Comedocarcinoma with central necrosis surrounded by papillary, cribriform or solid masses |

3.

A repeat biopsy is indicated within 3–6 months in the presence of atypical small acinar proliferation (ASAP) as this is associated with a subsequent PC diagnosis in 40 % of patients [37]. It is also performed when extensive prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) is seen on multiple sites (≥2 cores) carrying a 20–30 % risk of cancer [38, 39], as well as when the PSA is rising with the appearance of a prostate nodule during regular follow-up. However non-extensive (unifocal) high-grade PIN as an isolated finding is no longer considered an indication for repeat biopsy [40] unless there are new changes suggesting disease progression, i.e. PSA increase or appearance of a nodule on DRE during subsequent follow-up. Here it is recommended to perform MRI in order to define the suspected zone. If MRI is not available, 4–6 biopsies should be taken at the apex and the transitional zone in addition to the standard 12 biopsies [41]. A saturation biopsy exceeding 20 cores can also be recommended in highly suspicious cases with a previous negative biopsy. The incidence of PC detected in such circumstances is reported to be between 30 and 43 % [42].

3.5 Disease Extension Investigations

Once a positive diagnosis of PC is confirmed by histopathology, an image-based study is sometimes indicated to define whether the disease is localized, locally advanced or metastatic. After this study, the disease’s clinical tumours-nodes-metastases (cTNM) staging can be documented as per the 2010 AJCC cancer staging which is identical to the UICC classification [43] (Table 3.2). The pathological (pTNM) staging can only be established after radical prostatectomy, when the pathologist will be provided with the complete prostate specimen including the seminal vesicles and sometimes the pelvic LN.

Primary tumour (T) | |

TX | Primary tumour cannot be assessed |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumour |

T1 | Clinically inapparent tumour neither palpable nor visible by imaging |

T1a | Tumour incidental histological finding in 5% or less of tissue resected |

T1b | Tumour incidental histological finding in more than 5% of tissue resected |

T1c | Tumour identified by needle biopsy (e.g. because of elevated PSA) |

T2 | Tumour confined within the prostate (tumour found in one or both lobes by needle biopsy, but not palpable or reliably visible by imaging, is classified as T1c) |

T2a | Tumour involves one-half of one lobe or less |

T2b | Tumour involves more than one-half of one lobe but not both lobes |

T2c | Tumour involves both lobes |

T3 | Tumour extends through the prostate capsule (invasion into the prostatic apex or into, but not beyond, the prostatic capsule is classified not as T3 but as T2) |

T3a | Extracapsular extension (unilateral or bilateral) |

T3b | Tumour invades seminal vesicle(s) |

T4 < div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |