Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCA) can be classified into three main categories: localized (confined to the gland), locally advanced (extending beyond the prostate capsule with or without nodal involvement) or metastatic. External beam radiation (EBRT), brachytherapy, cryosurgical ablation of the prostate and radical prostatectomy (RP) provide good long-term disease control in patients with pathologically localized disease [1]. The same cannot be said for locally advanced PCA. The definition of locally advanced prostate varies among experts in the field. Some restrict the definition to patients with T3 (extracapsular extension and/or seminal vesicle invasion) or T4 (invasion of surrounding organs/tissue), while others include node-positive disease [2]. Some reports include patients with high-risk features such as serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) > 20 mg/mL or high Gleason score 8–10; still others consider patients who are status post prostatectomy with high-risk features such as positive margins, extracapsular extension, positive lymph nodes or seminal vesicle invasion [3]. In this chapter, locally advanced PCA will be defined to include pT3–4 N0–1 M0 (with or without positive margins) tumors.

Even patients with apparently clinically localized disease may be at significant risk for treatment failure. In 1998, d’Amico et al. reported on a staging system to stratify patients into groups with a low, intermediate or high risk of biochemical recurrence after definitive therapy [4]. Men at high risk for treatment failure were characterized as having ≥ clinical T2c disease or serum PSA > 20 ng/mL or Gleason score ≥ 8, and/or > 50% positive cores on biopsy [5,6]. When using single-modality treatment, these high-risk men have 5-year disease-free survival rates of 30–50%, and the optimal treatment choice remains controversial [4]. Thus, the optimal choice of treatment for locally advanced PCA remains controversial, as neither primary EBRT alone nor RP alone appears to lessen treatment failure rates in these high-risk patients.

Though the advent of PSA screening has allowed for earlier detection of PCA, 25% of patients are found to have pathological T3–4 disease [7], and the risk of biochemical recurrence is as high as 67% at 5 years in these patients [8]. Despite the advances that have been made in the treatment of PCA, there is currently no consensus on the treatment of patients who present with palpable disease outside the prostate. With this in mind, the focus of this chapter is to present the highest levels of evidence available to guide urologists with respect to the management of locally advanced PCA.

Clinical question 28.1

In men with locally advanced prostate cancer, does neo-adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy prior to RP improve clinical outcomes?

Background

Systemic hormone therapy was first combined with RP by Vallet in 1944 [9]. However, Vallet’s approach, which involved depriving the prostate of androgen by means of surgical castration, received little attention until safer, reversible forms of androgen deprivation therapy became available in the 1980s [10].

Literature search

Evidence was obtained by performing a systematic literature search using PubMed. The search was performed with the terms “neo-adjuvant,” “androgen deprivation,” and “prostate cancer” combined with the clinical query filter function to limit the search to the English language. A search limit was also utilized to search for those articles categorized as a clinical trial, meta-analysis or randomized controlled trial.

The evidence

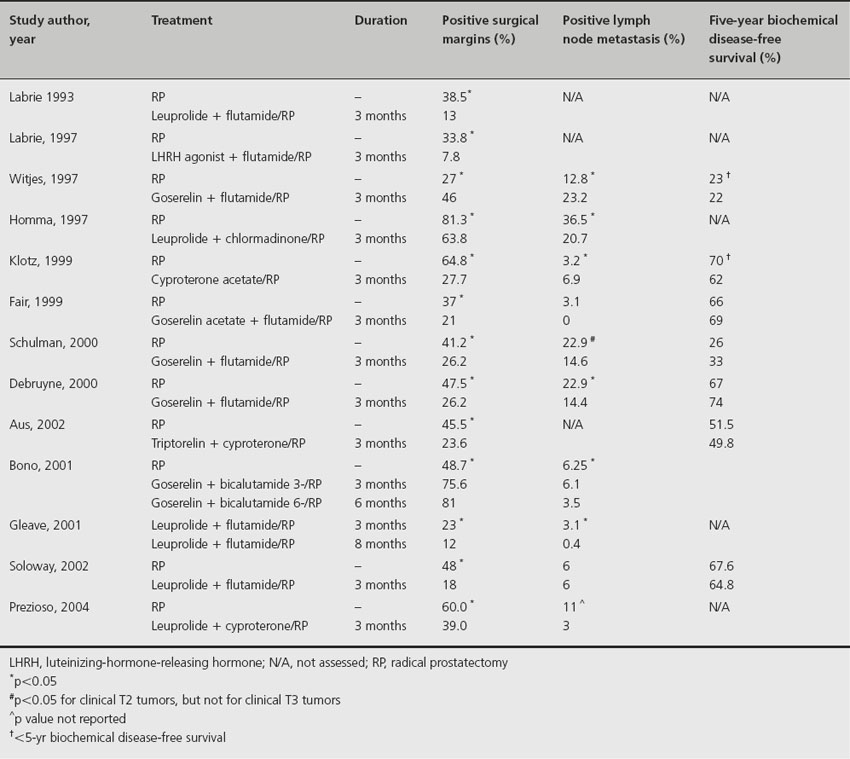

Since the 1980s several prospective randomized trials have demonstrated the efficacy of neo-adjuvant hormonal therapy (Table 28.1). Such therapy has been associated with a decreased incidence of both positive surgical margins and positive lymph node metastasis, and an increased incidence of pathological pT0 tumors [11]. The latter finding, though promising, must be viewed with caution, however, since meticulous pathological studies suggest that at least 65% of specimens classified as pT0 after hormonal therapy still contain persistent tumor [12]. Unfortunately, no neo-adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy to date has succeeded in producing either a complete pathological response or a significant improvement in long-term biochemical disease-free survival (i.e. as determined on the basis of serum PSA level). Though an important prognostic factor in various cancers including tumors of the breast and lung [13,14], complete pathological response is difficult to achieve in prostate tumors because of their well-known refractoriness to therapy.

Table 28.1 Randomized clinical trials of neoadjuvant hormonal therapy

Comment

While neo-adjuvant hormonal therapy was generally considered safe and may result in reductions in tumor size, serum PSA levels, and the incidence of positive surgical margins and positive nodal metastasis, recent studies have emphasized the potential harm associated with hormonal therapy, even when administered short term. Most importantly, though, there is no evidence that it improves biochemical disease-free or overall survival.

Recommendation

Based on high-quality and consistent evidence, we make a strong recommendation against neo-adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy prior to RP (Grade 1A).

Clinical question 28.2

In men with locally advanced prostate cancer, does neo-adjuvant chemotherapy prior to RP improve clinical outcomes?

Background

Chemotherapy is used today mainly in patients with metastatic, hormone-refractory prostate cancer. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved mitoxantrone for use in this population after it was shown that approximately one-third of symptomatic patients had an improvement in pain, even though no survival advantage was seen [15,16]. Subsequently, the FDA approved the use of docetaxel after the results of two trials demonstrated its efficacy in this population. The first was TAX 327, which randomized 1006 men to docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone. The median survival of all patients treated with docetaxel was 18.2 months compared with 16.4 months for those treated with mitoxantrone [17]. The second study, SWOG 9916, randomized 770 men to docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone. The median survival for patients treated with docetaxel was 18.9 months compared with 16 months for mitoxantrone. Subjects in this study treated with docetaxel reported less pain and improved quality of life compared to the mitoxantrone groups [18].

To improve survival in patients with locally advanced PCA, a multimodal approach combining local and systemic therapies is likely needed. Neo-adjuvant therapies have the benefit over adjuvant therapy of potentially being able to treat micrometastatic disease that may lead to failure of local therapy, cytoreduce (downstage) locally advanced tumors, making them more amenable to a successful surgical resection with negative margins, and confirm treatment efficacy by assessing postoperative tissue specimens. Investigators in the field of breast cancer have seen improved survival rates in large, locally advanced breast cancers with the use of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy [19,20], and prostate cancer researchers have followed by studying the use of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy prior to RP.

Literature search

Evidence was obtained by performing a systematic literature search using PubMed. The search was performed with the terms “neo-adjuvant,” “chemotherapy,” and “prostate cancer” combined with the clinical query filter function to limit the search to the English language. A search limit was also utilized to search for those articles categorized as a clinical trial, meta-analysis or randomized controlled trial.

The evidence

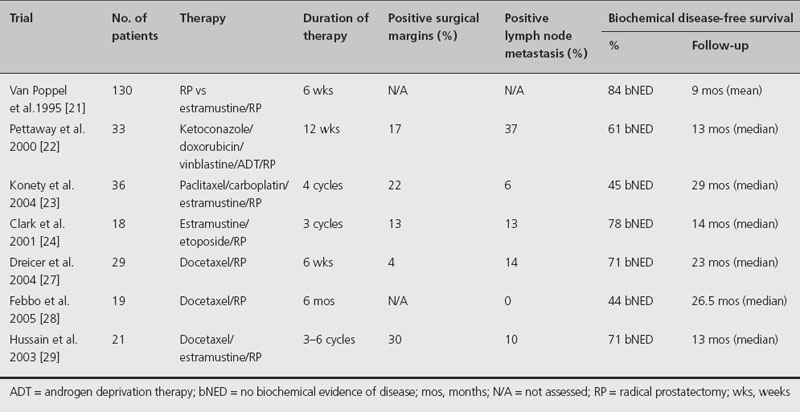

There are no adequately powered randomized studies that have been completed evaluating the use of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy prior to RP. However, there have been several promising clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of these neo-adjuvant regimens (Table 28.2). In one of the larger trials, van Poppel et al. randomized 130 patients with clinical T2b and T3 disease to either 560 mg of estramustine daily for 6 weeks prior to RP, or RP alone [21]. Although the positive surgical margins rates decreased in the neo-adjuvant group, this benefit did not extend to patients with clinical T3 tumors [21].

Table 28.2 Clinical trials using neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Pettaway et al. performed a phase II study in which 33 patients with high-risk disease characterized as being clinical stage T1–2, Gleason score ≥ 8, or T2b–T2c, Gleason score of 7 and serum PSA level greater than 10 ng/mL or clinical stage T3 received 12 weeks of ketoconazole and doxorubicin alternating with vinblastine, estramustine, and androgen ablation followed by prostatectomy [22]. Due to the estrogenic effects of estramustine, a small percentage of patients (6%) developed thromboembolic events. On pathological evaluation, 33% of the patients had organ-confined disease, 63% had negative lymph nodes, and 17% had positive surgical margins. Serum PSA was undetectable postoperatively in all patients. At a median follow-up of 13 months, 61% showed no biochemical evidence of disease. However, the primary goal of achieving a 20% rate for pT0 status was not achieved in this study [22].

Konety et al. performed a phase II study of 36 patients with locally advanced (stage T3 or greater) and/or high-risk tumors (Gleason score 8–10 and/or serum PSA greater than 20 ng/mL) who received four cycles of paclitaxel, carboplatin and estramustine followed by RP [23]. Deep vein thrombosis (22%) was the most frequent complication of chemotherapy, again attributable to the estrogenic effects of estramustine. The positive surgical margin rate was 22%. The clinical stage was reduced in 39% of patients. At a median follow-up of 29 months, 45% remained free from biochemical recurrence. The clinical stage was reduced in 39% of patients [23].

Clark et al. reported on a phase II trial of 18 patients with high-risk disease (clinical stage T2b/c or T3, PSA level ≥ 15 ng/mL, and/or Gleason score ≥ 8) who received neo-adjuvant estramustine and etoposide before RP [24]. Only 16 of the patients actually underwent RP. Five patients (28%) experienced grade 3 toxicity (two with deep venous thrombosis, two with neutropenia, and one with diarrhea) and one (6%) experienced grade 4 toxicity (pulmonary embolus) before surgery. Organ-confined disease was observed in 31% and disease was confined to the prostatectomy specimen in 56%. Half of the patients achieved an undetectable PSA after neo-adjuvant therapy and prior to RP. All patients had an undetectable PSA postoperatively, and at a median follow-up of 14 months after RP, 78% had no biochemical evidence of disease [24].

Since the approval of the use of docetaxel in hormone-refractory PCA, trials have been performed demonstrating its safety in a neo-adjuvant setting [25,26]. Dreicer et al. performed a phase II trial consisting of 29 men with high-risk disease (clinical stage T2b–T3, PSA > 15 ng/mL, and/or Gleason score ≥ 8) who received six doses of docetaxel 40 mg/m2 intravenously administered weekly for 6 weeks followed by RP. On pathological review, only 11% had organ-confined disease, 89% had extracapsular extension, 14% had lymph node metastasis, and there were no pathological complete responders to docetaxal. While 79% of patients experienced some reduction in PSA level post chemotherapy, 24% of patients had more than a 50% reduction in PSA level in response to docetaxel alone. Postoperatively, 71% of the subjects are free from biochemical recurrence at 23 months follow-up. No unexpected toxicities or intraoperative complications occurred [27].

Febbo et al. performed a trial utilizing docetaxel in a neo-adjuvant fashion prior to RP in 19 patients with high-risk PCA (clinical stage T3, PSA ≥ 20 ng/mL, and/or Gleason score 4 + 3 = 7 or greater) [28]. The patients received weekly docetaxel (36 mg/m2) for 6 months, followed by RP. A reduction of at least 25% and 50% of tumor volume was seen in 68% and 21% as measured by endorectal MRI, respectively. Sixteen of the 19 patients completed the chemotherapy regimen and underwent RP. On pathological evaluation, 38% had organ-confined disease, 62% had extracapsular extension, and none had lymph node metastasis. As with all the other neo-adjuvant chemotherapy trials, there were no pathological complete responders. Toxicity consisted of mostly grade 1 and 2 fatigue and mild gastrointestinal effects such as taste disturbance, nausea, and diarrhea. At a median follow-up of 26.5 months, 7 out of 16 (44%) patients remained free of biochemical recurrence [28].

Hussain et al. combined the use of estramustine, which alters androgen metabolism, with docetaxel in 21 patients with high-risk PCA (clinical stage T2b or greater, PSA ≥ 15 ng/mL, and/or Gleason score ≥ 8) [29]. The chemotherapy regimen consisted of docetaxel (70 mg/m2) and estramustine (280 mg three times daily) for 3–6 courses. Ten patients underwent RP, with negative surgical margins in seven patients (70%). There was one episode of grade 4 neutropenia, with the remainder of toxicities being mainly grade 3 neutropenia and deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Despite the use of aspirin, three of the first seven patients developed DVTs due to the use of estramustine. Low-dose warfarin was subsequently given to the remaining patients and no further DVTs occurred. At a median follow-up of 13 months, 71% of patients remained free of biochemical recurrence [29].

The success of docetaxel in hormone-refractory prostate cancer, along with the results of the aforementioned phase II neo-adjuvant chemotherapy studies, led to the development of a phase III trial by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 90203), randomizing patients with clinical T1–T3a NX M0 PCA to either RP alone or a chemohormonal therapy regimen consisting of leuprolide acetate or goserelin for 18–24 weeks as well as six cycles of docetaxel followed by RP [30]. The entry criteria also stipulated that the patients have high-risk disease with either a Gleason score of 8–10 or a probability of biochemical progression-free survival at 5 years after surgery less than 60% by Kattan nomogram prediction [31]. The goal of the trial is to enroll 750 patients, with the primary outcome being the 3-year biochemical progression-free survival rate. The trial was opened in July 2007 and as of 30 June 2008, it had accrued only 35 patients [32].

Comment

The use of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy prior to RP is tolerated reasonably well and is associated with a decrease in both serum PSA levels and positive surgical margins. However, none of the agents studied to date has resulted in a pathologic complete response. The median follow-up in these neo-adjuvant trials was at most 29 months. As researchers have learned from the neo-adjuvant hormonal trials, a decrease in positive surgical margins does not necessarily translate into an improvement in biochemical disease-free survival [33,34]. Further randomized control trials are necessary to evaluate the efficacy of these neo-adjuvant agents. It is critical that urologists work in conjunction with oncologists to enroll patients into these neo-adjuvant chemotherapy protocols to substantiate these trials and prevent them from closure due to lack of accrual. Therefore, longer-term follow-up data are necessary to determine if these patients are free of disease in the long term and if there is an impact on overall survival.

Recommendation

The studies reviewed were either of very low quality or were early phase trials that were not designed to compare neo-adjuvant chemotherapy to the standard of care. Therefore, the authors can make no recommendation for the use of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy prior to RP.

Clinical question 28.3

In men with pathological T3 disease or pathological T2 with positive margins after RP, does adjuvant radiation therapy improve clinical outcomes?

Background

As previously noted, patients with adverse pathological features, such as extracapsular extension, seminal vesicle invasion or positive margins, after RP have up to a 67% chance of biochemical recurrence at 5 years [35]. Failure is thought to be due to occult local or systemic disease not eradicated by surgery. The purpose of adjuvant radiation is to sterilize any residual tumor cells in the prostate bed following RP, with the ultimate goal of decreasing local and biochemical recurrence and improving overall survival.

Literature search

Evidence was obtained by performing a systematic literature search using PubMed. The search was performed with the terms “adjuvant,” “radiation therapy,” and “prostate cancer” combined with the clinical query filter function to limit the search to the English language. A search limit was also utilized to search for those articles categorized as a clinical trial, meta-analysis or randomized control trial.

The evidence

Several RCTs have been performed [36–39] comparing RP followed by immediate adjuvant radiation therapy to RP alone in men with pathological T3 disease or pathological T2 with positive margins (Table 28.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree