Fig. 11.1

CT of a blunt pancreatic injury

Fig. 11.2

CT of a gunshot wound of the liver and pancreas

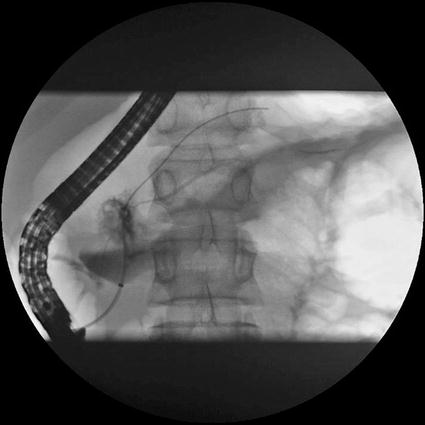

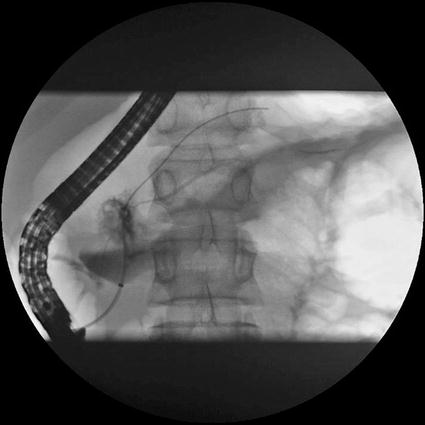

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is very useful in identifying injuries to the main pancreatic duct (Fig. 11.3), but it is seldom available in the acute setting. Magnetic resonance imaging pancreatography (MRP) can detect pancreatic injuries and sometimes exclude a pancreatic duct injury (Figs. 11.4 and 11.5), but its reliability has not yet been established.

Fig. 11.3

ERCP of a grade IV injury to the pancreas

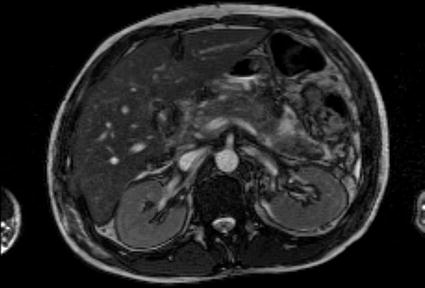

Fig. 11.5

MRP reveals the intact main pancreatic duct confirming a grade II injury

11.3 Grading of Pancreatic Injury

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma has published the most commonly used scales for grading individual organ injuries. The injuries are graded from I to V with increasing severity. In pancreatic injuries (Table 11.1), the scale is very useful in determining the management strategy, both pre- and intraoperatively [4].

Grade | Injury | Description |

|---|---|---|

I | Hematoma | Minor contusion without duct injury |

Laceration | Superficial laceration without duct injury | |

II | Hematoma | Major contusion without duct injury or tissue loss |

Laceration | Major laceration without duct injury or tissue loss | |

III | Laceration | Distal transection or parenchymal injury with duct injury |

IV | Laceration | Proximal transection or parenchymal injury involving ampulla |

V | Laceration | Massive disruption of pancreatic head |

11.4 Nonoperative Management

In the absence of associated injuries requiring surgical repair, pancreatic contusions and minor lacerations (grades I and II) can be treated nonoperatively. In a series of 35 low-grade blunt pancreatic injuries, five patients failed nonoperative management due to missed bowel injuries or pancreatic abscess or fistula [5]. Occasionally, a minor leak or a side fistula of the pancreatic duct can be managed with an endoscopically placed stent.

11.5 Operative Management

The key maneuvers in the surgical management of pancreatic trauma are exposing the whole pancreas and assessing the state of the main pancreatic duct. Visualization of the entire pancreas can be started by transecting the gastrocolic ligament to allow inspection of the anterior surface and inferior border of the gland. The Kocher maneuver mobilizing the second part of the duodenum and the pancreatic head allows the examination of the head and uncinate process of the pancreas. Additional exposure of the superior border of the head and body of the pancreas can be achieved by transection of the gastrohepatic ligament. To complete the exposure, lateral mobilization of the spleen (Fig. 11.6), splenic flexure of the colon, and the dissection of the retroperitoneal attachments of the inferior border of the pancreas allow the visualization and bimanual palpation of the posterior surface of the tail and body of the gland [6].

Fig. 11.6

Mobilizing the tail of the pancreas with the spleen

The next step in assessing the severity of the pancreatic injury is the determination whether the main pancreatic duct is intact. Complete transection that sometimes can be sealed with a hematoma under the pancreatic capsule, central perforation (Fig. 11.7), large vertical laceration, and severe contusion especially in the distal part of the gland are indicative of disruption of the main pancreatic duct. Attempts at verifying the ductal injury with radiological means (intraoperative cannulation of the papilla through duodenotomy, intraoperative ERCP) or injecting dye are often cumbersome and unreliable.

Fig. 11.7

Central perforation in the neck of the pancreas (grade IV)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree