Grade I

Contusion or hematoma

Hematuria, subcapsular non-expanding hematoma

Grade II

Laceration

<1 cm parenchymal depth without collecting system invasion

Grade III

Laceration

>1 cm parenchymal depth without collecting system invasion

Grade IV

Laceration

Collecting system injury, segmental venous injury

Grade V

Laceration

Main vessel injury including thrombosis or avulsion

The use of proper CT scan protocol is pivotal to include the nephrogenic, vascular, excretory, and delayed images to evaluate the upper, mid-, and lower urinary tract. Low-grade injuries (grades 1–3 lacerations) from blunt abdominal trauma are not often associated with adjacent intra-abdominal organ damage resulting in conservative management. Conversely, higher-grade renal injuries may have concomitant abdominal organ injuries. Higher-grade renal injuries may require interventional radiological procedures or surgery that may range from placement of endovascular stents for renal artery injury or ureteral stenting for urinary extravasation or partial/total nephrectomy. In case of shattered kidney, one may consider conservative management when patients are hemodynamically stable.

15.1.2 Management

The absolute indications for immediate surgical exploration include but are not limited to life-threatening hemorrhage from a renal vessel laceration that may not be managed by interventional radiological procedure, expanding or pulsatile hematoma, shock, and usually patients that suffered penetrating trauma. In cases of patients that require immediate laparotomy without prior imaging, a “one-shot” IVP may be completed with injection of 1–2 mL/kg (maximum of 150 cc) of iodine contrast to evaluate presence of two renal units in case of nephrectomy is needed.

The midline laparotomy is recommended to allow complete exposure of all abdominal organs. The use of self-retaining retractors is often helpful. Renal vascular control may be performed by two distinct methods: (1) via an incision through the mesentery, just proximal to the inferior mesenteric artery identifying the renal vessels isolating with vessel loops, or (2) by incision of the line of Toldt, rapid mobilization and medial rotation of the colon, and manual control of the renal vessels with anterior and posterior bimanual control [5]. The method of choice will depend on surgeon’s experience, and it remains controversial whether one method is superior to the other to prevent total nephrectomy rates. There have been several studies evaluating selective angiography, stent placement, and embolization in patients with grade V renal lacerations who otherwise would not require a laparotomy (Fig. 15.1) [6, 7].

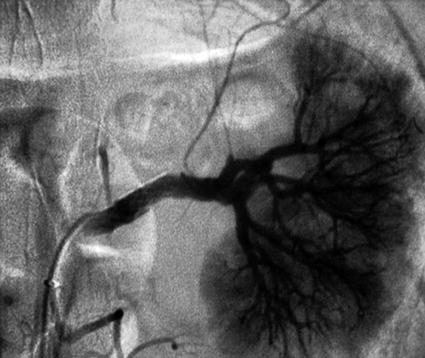

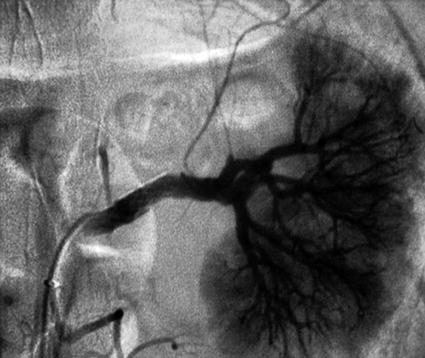

Fig. 15.1

Grade V renal injury with Palmaz stent intervention

Blast effect from missile injuries may cause severe tissue damage mandating debridement and repair of the renal parenchyma and use of omental wrap to cover the injured site. The omental wrap must be always considered to prevent delayed complications such as urinoma or abscess in areas that are devascularized.

Renal injury patients with urinary extravasation can be observed provided there are no other associated injuries. Up to 90 % of these injuries will resolve spontaneously. But if electrolyte or creatinine levels increase and signs of peritoneal irritation and ileus are evident, one may consider ipsilateral ureteral stent placement and Foley catheter drainage until extravasation resolves. Imaging may be recommended when continued extravasation is suspected with no resolution [8].

In cases of persistent or infected urinoma, percutaneous drain placement must be considered until the process is resolved.

15.1.3 Follow-Up

Although long-term effects of renal trauma have been studied, follow-up is often difficult. Renal function may decrease 15, 30, and 65 % in patients with grades 3, 4, and 5 lacerations, respectively [9]. Nuclear renal scan are not helpful to evaluate renal function post-acute injury. Also, no difference in functional outcomes was seen between surgical and nonoperative patients [10]. Hypertension can also exist following trauma and may occur within the first 6 months post-trauma. Mechanisms for postrenal trauma hypertension include stenosis of main or segmental renal artery branch (Goldblatt kidney) or prolonged subcapsular compression from a hematoma on the kidney (Page kidney). These often resolve and rarely require curative nephrectomy. One may also follow-up with urine analysis to detect proteinuria.

15.2 Ureteral Trauma

Acute traumatic ureteral injuries are rare and occur in less than 1 % of overall trauma and less than 5 % of abdominal trauma. More than 80 % of these injuries are from gunshot wounds. The rest are split between stab wounds and blunt abdominal trauma [11]. However, the majority of ureteral trauma cases are due to intraoperative injury. The injuries range from sharp transection or suture ligation to thermal damage from energy devices. A common location for intraoperative injury is the distal ureter. The most common setting for this occurrence is abdominal hysterectomy, in which up to 3–12 % of cases involve distal ureteral injury. During emergent caesarean sections when there is lateral extension of the incision, distal ureteral injury is an adverse event due to low visibility if bleeding ensues from the uterine artery that is located anterior to the distal ureter. Low anterior or abdominoperineal resections, as well as vascular procedures such as aortoiliac bypass, can also lead to ureteral injury. The number one ureteral injury or perforation is done by urologists performing ureteroscopy. The risk of ureteral avulsion during ureteroscopy has been reported at 0.3 %, while perforation is reported in up to 2–6 % of cases [12] and may have delayed diagnosis in up to 50–70 % of cases [13].

15.2.1 Diagnosis

Extravasation of contrast is seen on imaging when ureteral transection occurs [14].

The most sensitive modality to evaluate ureteral injury is with retrograde urethrogram under fluoroscopic evaluation, but a CT intravenous pyelogram (IVP) with delayed excretory phase images is comparably effective.

In cases of patients that require immediate laparotomy without prior imaging, either a “one-shot” IVP may be completed on the operating table or injection of methylene blue may be performed into the renal pelvis and visualized either in the Foley catheter if the system is intact or in the abdomen if there is presence of ureteral injury.

15.2.2 Management

Managing ureteral injuries can be challenging depending on the location and the degree of injury. One must follow the following principles when reconstructing two disrupted ends of the ureter in any location along its course: (1) appropriate debridement of ureteral ends with good spatulation and vascular supply, (2) good mucosa apposition, (3) water-tight anastomosis with absorbable suture, (4) tension-free anastomosis, and (5) use of omental wrap, if possible, and placement of ureteral stent.

Ureteropelvic junction disruption is a surgical emergency. Pyeloplasty is recommended with a ureteral stent placement following abovementioned principles of anastomosis.

Partial sharp transection can be closed primarily with absorbable suture, preferably with ureteral stent placement. Thermal injuries and contusions, including bullet wounds, require wide debridement due to blast effect and to minimize risk of anastomosis devascularization and late failure. The stent should remain in place for 6 weeks with absence of urine leakage with CT-IVP. Important factors include ureteral length and blood supply. Often the deciding factor on type of repair is determined by location (Table 15.2). Upper and mid-ureteral trauma often may be repaired primarily. In mid-ureteral trauma an omental wrap is highly recommended due to the poor vascular supply. Lastly, the distal ureter may be reimplanted into the bladder with a psoas hitch or Boari flap.

Table 15.2

Ureteral repair options based on ureteral injury location

Upper third | Ureteroureterostomy, ureterocalycostomy, transureteroureterostomy, renal autotransplantation, stent placement |

Middle third | Ureteroureterostomy, Boari flap, transureteroureterostomy, stent placement |

Lower third | Psoas hitch with ureterocystostomy, Boari flap, ureteral re-implant, stent placement |

Extensive injury | Ileal ureter, autotransplantation, nephrectomy |

Partial injury | Stent placement |

15.2.3 Follow-Up

Either a CT-IVP or CT cystogram in cases of ureteroneocystostomy will be required to ascertain no urine leakage prior removal of ureteral stent at least 4 weeks after repair.

15.3 Bladder Trauma

Over 85 % of bladder injuries are due to blunt trauma, and only approximately 10 % are isolated. Ninety percent of traumatic bladder injuries are related to pelvic fractures and most often also present with hematuria [15]. Bladder injuries are often classified as extraperitoneal (60 % of cases) or intraperitoneal. Extraperitoneal bladder rupture is usually caused by a pelvic fracture and occurs on the anterolateral portion of the bladder.

15.3.1 Diagnosis

Historically bladder injuries were diagnosed by voiding cystogram with 250–300 cc of contrast into the bladder, including lateral and oblique views and post-void films. Nowadays, during a trauma work-up a delayed imaging CT scan can indicate bladder trauma, and it is informally called indirect CT cystogram. However, the most accurate imaging modality is a CT cystogram with at least of 250 cc of contrast into the bladder [16].

The bone windows in the CT scan can also diagnose pelvic fractures, and presence of contrast extravasation outlining the bowel will indicate intraperitoneal bladder rupture, often at the dome of the bladder. The extraperitoneal bladder rupture will demonstrate contrast extravasation in the retropubic space called “sunburst” or speculated manner (Fig. 15.2).

Fig. 15.2

A fluoroscopic cystogram revealing an intraperitoneal bladder injury

Additional imaging modalities include fluoroscopic cystogram intraoperatively with or without use of cystoscopic evaluation.

Similar to ureteral injury, a common etiology for bladder injury is iatrogenic trauma. Traditionally, bladder trauma is often seen in open or laparoscopic pelvic surgery.

15.3.2 Management

Historically, extraperitoneal bladder injuries have been managed with a large French Foley catheter with appropriate urine drainage and proper evacuation of possible blood clots without the need of a suprapubic catheter [17]. Adequate drainage for at least 10 days with an indwelling catheter and a CT cystogram must be performed prior removal of urethral catheter. Recently, reports advocate repair of extraperitoneal bladder injuries in order to decrease convalescence and morbidity, especially during internal fixation of a pelvic fracture [18]. Another current modality is the laparoscopic repair of isolated intraperitoneal bladder injury [19].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree