Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains the second leading cause of cancer mortality among men, and the third leading cause among women. Worldwide, CRC is the fourth most common cancer with approximately 1 million new cases annually. Unfortunately, advanced disease at diagnosis is still all too common. Locally advanced rectal cancer, node-positive colon cancer, and metastatic disease still compose a significant proportion of colon and rectal cancer. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment, providing definitive management and potential cure in early cases, and effective palliation in advanced cases. Chemotherapy and, sometimes, radiotherapy are essential components of effective treatment. This article briefly reviews the general principles of surgical management and describes recent developments.

Colon and rectal adenocarcinoma was projected to afflict 153,800 Americans in 2007 and was estimated to cause more than 52,000 deaths . Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains the second leading cause of cancer mortality among men, and the third leading cause among women. Worldwide, CRC is the fourth most common cancer with approximately 1 million new cases annually. North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand are high-risk regions . Unfortunately, advanced disease at diagnosis is still all too common. Locally advanced rectal cancer, node-positive colon cancer, and metastatic disease still compose a significant proportion of colon and rectal cancer . Surgery is the mainstay of treatment, providing definitive management and potential cure in early cases, and effective palliation in advanced cases. Chemotherapy and, sometimes, radiotherapy are essential components of effective treatment. This article briefly reviews the general principles of surgical management and describes recent developments.

General Principles of Surgical Treatment

CRC is generally diagnosed by colonoscopy or contrast radiography. An increasing percentage of cases are first detected by abdominal CT. Surgical planning is influenced by the cancer location, the clinical stage, and other factors, such as comorbid conditions, patient frailty, and prior surgery. Preoperative colonoscopy provides a secure histologic diagnosis and determines whether the remainder of the colon is clean of polyps or synchronous cancers. A preoperative CT scan provides additional staging information and assesses whether adjacent vital structures, such as the ureters (for low pelvic lesions) or the duodenum (for right transverse colon lesions), are involved. The local extent of rectal carcinoma is best assessed by endorectal ultrasound, as described in an accompanying article by Bhutani, elsewhere in this issue. Neither histologic grade nor molecular markers currently influence the contemplated surgery, but these factors may become important in subsequent therapy. Similarly, serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels do not influence preoperative decision making, but may assist in postsurgical monitoring.

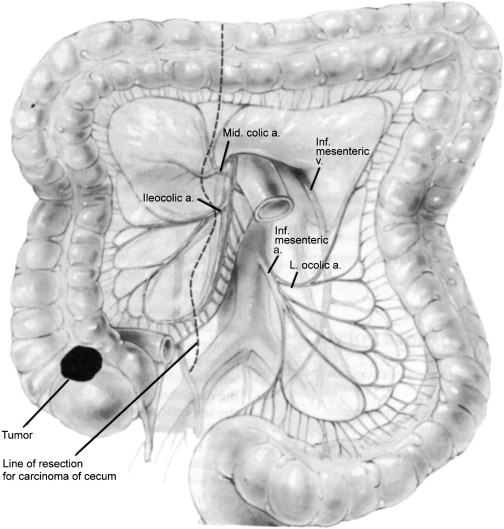

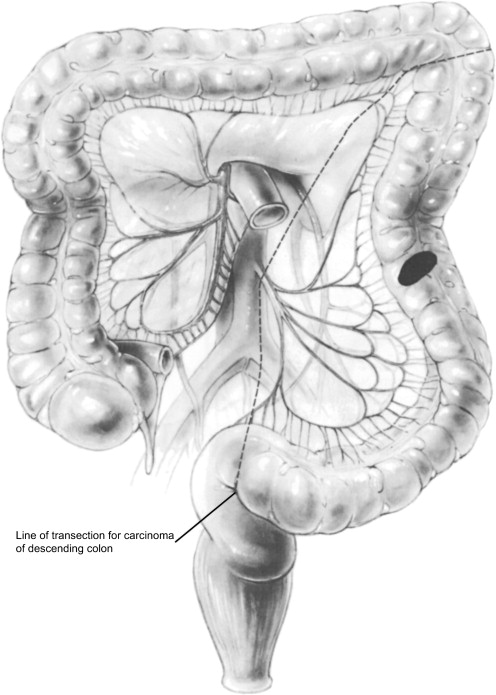

Resection is based on standard anatomic regions according to the regional lymphatic drainage and blood supply ( Figs. 1 and 2 ). An adequate lymphadenectomy should remove all draining lymphatics at risk for metastatic involvement. Numerous large clinical trials have demonstrated that surgery alone results in a 5- or 10-year survival of 50% to 60% for stage III cancer . The Cancer Staging Handbook of the American Joint Committee on Cancer recommends that at least 12 lymph nodes draining the primary cancer should be excised and examined to ensure proper staging and provide adequate surgical clearance . For cancers above the peritoneal reflection, the length of colon resected is generally determined by the mesenteric vascular segmental anatomy and the surgical margins are usually ample. Frozen sections are rarely required.

Below the peritoneal reflection, the desire for wide surgical margins must be balanced against sphincter preservation. The most difficult margin to control may, in fact, not be the longitudinal margin (ie, distance from the cancer to the sphincters) but the radial margin using the total mesorectal excision (TME) technique. This technique has been thoroughly analyzed, and is now considered standard for rectal cancer. The role of staging and neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer is discussed later.

Approximately 5% of patients who undergo colon cancer surgery have synchronous lesions. The management depends on the relative location of the synchronous lesions, family history, patient age, and other factors. Most surgeons prefer an extended resection encompassing both lesions with a single anastomosis, rather than two discontinuous segmental resections with two anastomoses. Subtotal colectomy may be required to accomplish this goal.

High-risk situations, such as chronic ulcerative colitis with severe dysplasia or familial adenomatous polyposis, are best managed by prophylactic surgery (restorative proctocolectomy) before carcinoma develops. When frank carcinoma is encountered in these situations, treatment of the existing malignancy takes precedence over prevention of a subsequent cancer, and a slightly more conservative resection, such as a subtotal colectomy, rather than restorative proctocolectomy or even proctocolectomy with ileostomy, may be elected to minimize complications.

In preparation for elective colon resection, the patient undergoes careful assessment of risk, including cardiac, pulmonary, and hematologic evaluation. Mechanical bowel cleansing is obtained by a combination of cathartics and enemas, or by antegrade lavage. If a CRC is nearly obstructing, the bowel preparation may require modification. Mechanical bowel preparation is supplemented by preoperative administration of antibiotics. Surgery is usually performed under general anesthesia. Epidural catheters are placed for postoperative pain control.

Right and Left Hemicolectomy

As an example of open colon resection, consider elective right hemicolectomy, performed for cancer of the cecum or ascending colon. The lateral peritoneal attachment is incised, and the colon is mobilized medially, to expose the right kidney, ureter, and duodenum. The peritoneum is incised over the base of the mesenteric vessels—in this case, the ileocolic artery and vein. Typically the colon is divided just proximal to the main trunk of the middle colic artery, to preserve a robust blood supply to the transverse colon, and the entire cecum and a few centimeters of terminal ileum are included in the resection. These points of division are identified and windows are made in the mesenteric surface of the bowel ( Fig. 3 ). The bowel is divided with a stapling device. The mesentery is divided between clamps and the resected specimen is removed. Gastrointestinal continuity is established by a stapled ( Fig. 4 ) or hand-sewn ( Fig. 5 ) anastomosis. The abdomen is closed without external drains.

When the lesion is in the left colon, particularly when below the peritoneal reflection, technical modifications allow restoration of intestinal continuity in the deep and narrow confines of the pelvis. The most common method is transanal insertion of a circular stapling device ( Fig. 6 ).

Unexpected findings at surgery can require surgical modifications. Despite preoperative workup, peritoneal implants or small hepatic metastases may be identified by careful palpation at surgery. Generally the surgeon proceeds with resection of the primary cancer as planned, and performs a biopsy to document the extent of metastatic disease. When a single isolated metastasis is identified, it may be excised. Controversy surrounds the issue of whether to resect a single hepatic metastasis. Surgeons often individualize this decision based on the size and ease of removal of the lesion. Often, a staged curative surgery is performed for isolated hepatic metastasis. Proper documentation of the presence or absence of peritoneal disease strongly impacts on the surgical decision. Standard therapeutic lymphadenectomy should be performed if future surgical management of metastatic disease is to be entertained. Aggressive debulking is generally not performed during the primary procedure. It may be elected later as part of comprehensive multimodality therapy.

Emergency surgery may be required for three cancer complications: colonic obstruction, bleeding, or perforation. The surgeon should endeavor to remove the cancer whenever possible, but the complication rate is higher and the quality of the resection is worse when this surgery is performed in an emergency situation. Restoration of gastrointestinal continuity is generally not feasible and the patient receives a colostomy. Preoperative marking of possible colostomy sites ensures proper placement of the stoma. With improvements in systemic therapy, many patients will survive for a significant time, and a functional stoma can positively impact on their quality of life.

Obstruction is the most common indication for emergency surgery. Surgery may be limited to a decompressive colostomy or may include resection of the cancer with creation of an end colostomy and distal blind pouch (Hartmann procedure). Primary anastomosis is ill advised because the proximal bowel is dilated and filled with feces. Temporizing endoscopic maneuvers (dilatation and stent placement) may permit colonic decompression without surgery that provides a period of time during which the medical condition can be optimized and the diagnosis confirmed. Elective resection may be performed thereafter under controlled conditions. Perforation of CRC is uncommon. It generally requires resection of the perforated colonic segment with creation of a proximal colostomy (Hartmann procedure). Bleeding that is sufficiently brisk to require surgery is rare.

The surgical treatment of an asymptomatic primary in the setting of advanced incurable cancer is uncertain. Fear of subsequent complications from the primary cancer needs to be balanced against delays in chemotherapy resulting from the surgery. Retrospective reviews demonstrate an acceptable complication rate, when the primary is left intact and untreated, of obstruction in 10% to 20%, bleeding in 4%, fistula formation in 4%, and perforation . Bleeding, perforation and obstruction, though uncommon, can occur in up to 20% and 30% of patients who survive more than 2 years after such surgery with an “intact primary.”

Right and Left Hemicolectomy

As an example of open colon resection, consider elective right hemicolectomy, performed for cancer of the cecum or ascending colon. The lateral peritoneal attachment is incised, and the colon is mobilized medially, to expose the right kidney, ureter, and duodenum. The peritoneum is incised over the base of the mesenteric vessels—in this case, the ileocolic artery and vein. Typically the colon is divided just proximal to the main trunk of the middle colic artery, to preserve a robust blood supply to the transverse colon, and the entire cecum and a few centimeters of terminal ileum are included in the resection. These points of division are identified and windows are made in the mesenteric surface of the bowel ( Fig. 3 ). The bowel is divided with a stapling device. The mesentery is divided between clamps and the resected specimen is removed. Gastrointestinal continuity is established by a stapled ( Fig. 4 ) or hand-sewn ( Fig. 5 ) anastomosis. The abdomen is closed without external drains.