Surgical Management of the Afferent Limb Syndrome

Carol E.H. Scott-Conner

Afferent limb syndrome is a specific constellation of signs and symptoms associated with partial or complete obstruction of the afferent limb of an upper gastrointestinal reconstruction. The syndrome was first described in 1881 as a complication of partial gastrectomy with Billroth II reconstruction. The term has been used to describe obstruction of one of the limbs of other upper gastrointestinal reconstructions, such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, in which a jejunal limb reconnects to another limb of jejunum carrying the stream of succus. That situation is usually due to an internal hernia and will not be further discussed here.

This chapter describes the pathogenesis, prevention, diagnosis, and surgical management of afferent limb syndrome after Billroth II gastrectomy. Because gastric surgery is much less common than it used to be, the peculiarities of the Billroth II gastrectomy are not as well understood by many surgeons. This is a condition that can be prevented by attention to several details during the original operation. Those details will be outlined here, and the remainder of the chapter will describe the surgical management.

Pathogenesis

Billroth II reconstruction involves a side-to-end anastomosis of a loop of jejunum to the gastric remnant. Two limbs are thus created: the afferent limb, which conveys bile and pancreatic juice to the gastric remnant and hence to the stream of chime; and the efferent limb which conveys food from the stomach into the small intestine. Clearly, either limb can become obstructed. This obstruction may be partial or complete, acute or chronic. When the obstruction involves the efferent limb, the diagnosis is relatively straightforward because the patient vomits food and is unable to eat. When the obstruction involves the afferent limb, the diagnosis is more subtle because food may still pass through in the normal manner and an upper gastrointestinal contrast study may well fail to demonstrate the etiology of the problem.

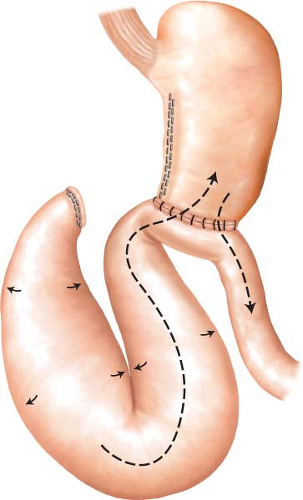

The term afferent limb syndrome is used to describe the chronic, partially obstructed situation (Fig. 26.1). Usually a problem is a kink or twist where the afferent limb attaches to the gastric remnant, but the obstruction can, in theory, be anywhere along the limb. Bile and pancreatic juice accumulate in the afferent limb until the pressure in the limb is sufficient to overcome the partial obstruction. During this phase, the patient typically experiences some degree of abdominal fullness or pain. When the obstruction is overcome, bile and pancreatic secretions flood the gastric remnant, often triggering bilious vomiting (and relief of pain). The vomitus generally contains little or no food, because the food has passed down the efferent limb without obstruction. Figure 26.1 shows some of the technical factors that contribute to the development of this syndrome: a long afferent limb, and anastomosis of the jejunum to the stomach in an isoperistalic fashion—that is, anastomosing the afferent limb to the lesser curvature and the efferent limb to the greater curvature.

When the obstruction is complete and occurs in the early postoperative period, blowout of the duodenal stump may occur. Thus, when a duodenal stump leaks, always check the afferent limb for obstruction. Complete obstruction late in the postoperative period may cause acute pancreatitis, or ischemic necrosis of the obstructed loop of jejunum.

Prevention

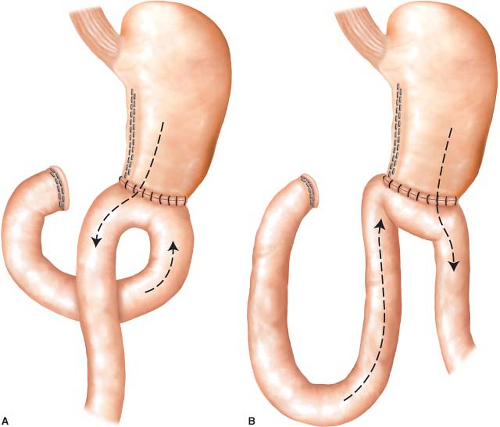

When creating a Billroth II reconstruction, the crucial factors to keep in mind to prevent afferent limb syndrome are these: Keep the afferent limb short, and anastomose the afferent limb to the greater curvature of the stomach rather than the lesser curvature in an antiperistaltic rather than an isoperistaltic fashion. The completed reconstruction should look like Figure 26.2A rather than Figure 26.2B.

In practice, this is easily accomplished by tracing the jejunum back to the ligament of Treitz. If you take the proximal jejunum in your two hands, flip the loop 180 degrees (by passing the distal part over the proximal part of the bowel), and then lay it against the gastric remnant, you will create the ideal geometry shown in Figure 26.2A

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree