Background

The lifetime risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer in the United States has almost doubled to 20% since the late 1980s, largely due to the widespread use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing. In fact, in 2008 alone, there will be an estimated 186,320 new cases of prostate cancer diagnosed in the US [1]. In addition, an estimated 28,660 deaths from prostate cancer will occur in 2008. Consequently, prostate cancer remains the most common solid malignancy (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancers) in American men and the second leading cause of cancer deaths among American men, representing an enormous public health challenge.

Despite the fact that prostate cancer is so prevalent, many aspects of its management remain controversial. Part of the dilemma arises from the fact that while many men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer, only a small percentage will die of it. The aim of this chapter is to present the data that guide clinicians on three important questions that arise with respect to the surgical management of clinically localized (stage T1–T2NXM0) prostate cancer.

One of the most controversial issues in the management of a patient with a newly diagnosed, clinically localized prostate cancer is whether or not any treatment should be recommended. And, if treatment is advised, which of the available treatments is best for a particular patient. Specifically, with respect to surgery, it is debated as to whether or not radical prostatectomy offers a survival advantage over expectant management, also referred to as watchful waiting.

At the root of this controversy are observational studies of the natural history of prostate cancer, which demonstrate that prostate cancer often manifests late in life and has a protracted clinical course [2]. The result is that up to 70% of men with prostate cancer and up to 90% of men with low-risk prostate cancer ultimately die of an unrelated cause. Another way of looking at it is that, on average, 1 in 5 or 6 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer, while only 1 in 35 will potentially die of it. These data often fuel the debate and are even more controversial when treatment-related side effects are factored into the decision making. Despite these sobering statistics, the fact remains that the majority of American men opt for initial treatment (67%) and surgery is the most common form of treatment chosen [3].

In this chapter, we focus on three important areas involving surgical management of localized prostate cancer. We evaluate the currently available data comparing oncological efficacy of surgery versus observation strategies such as watchful waiting and active surveillance. Next, we examine whether the experience of the surgeon or the hospital has an impact on perioperative outcomes, mortality and oncological efficacy. This is an area of emerging importance and is being recognized as an independent predictor of outcomes. It too is shrouded in controversy and has practical applications given that radical prostatectomy is technically demanding, coupled with the realization that the average urologist applying for recertification logs fewer than 10 cases per year. Finally, we address the issue of neo-adjuvant hormonal therapy prior to surgery as compared to surgery alone, an area that contains multiple randomized clinical trials available for analysis.

Clinical question 27.1

In considering management for clinically localized stage T1–T2 prostate cancer, is there a benefit to surgical intervention compared to watchful waiting?

Literature search

We performed a search of PubMed for any English-language studies published prior to July 2008 pertaining to this topic. We restricted our search to studies of open radical retropubic prostatectomy and limited the results to clinical trials. We included the following search terms in the queries: “watchful waiting” or “observation” or “surveillance” and “radical prostatectomy.”

The evidence

Randomized controlled trials

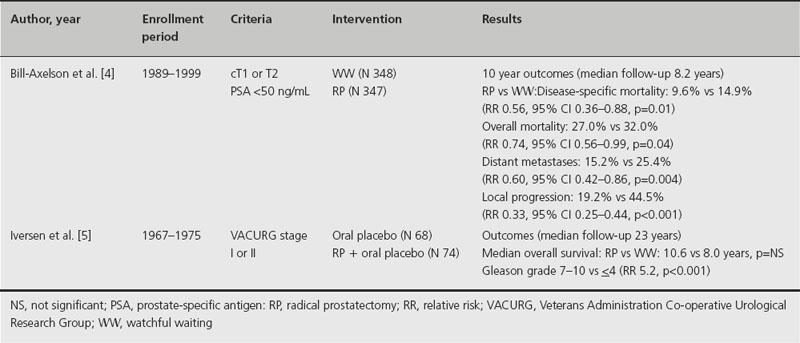

There are only two completed RCTs that compare survival outcomes in men with clinically localized prostate cancer who were randomized to surgery or watchful waiting [4,5]. These are presented in Table 27.1. In a high-quality randomized trial from the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group, Bill-Axelson et al. demonstrated advantages for radical prostatectomy over watchful waiting in a mixed population of clinically detected prostate cancer patients [4]. Whereas the earlier report with 5-year outcomes data had failed to demonstrate an overall survival advantage for surgery, the 10-year outcome data did reveal such an advantage. The absolute reduction in risk was 5% (27.0% vs 32.0%) and the corresponding relative risk of overall mortality in patients randomized to surgery was 0.74 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.56–0.99, p = 0.04). Radical prostatectomy also proved to have advantages over watchful waiting in reducing the risk of local progression (19.2% vs 44.3%), distant metastases (15.2% vs 25.4%) and disease-specific mortality (9.6% vs 14.9%). A prespecified subgroup analysis found that the advantage for radical prostatectomy in disease-specific mortality was limited to patients under the age of 65. However, as the authors point out, this analysis was exploratory and the study was not powered for such subgroup analyses.

Table 27.1 Randomized controlled trials comparing watchful waiting with surgery for management of clinically localized prostate cancer

This is an important landmark study because it is the first reliable evidence of a survival advantage for men with localized prostate cancer who undergo surgical treatment rather than watchful waiting. However, its applicability to the contemporary clinical presentation has been called into question. The population studied by the Scandinavian Group had clinically detected cancers (76% were palpable) that ranged from low-risk to high-risk disease, rather than screening-detected cancers that are more common in the US today. In fact, only 12% were detected based on a PSA elevation, which now constitutes the most common presentation among men in the US. Consequently, the population that was offered watchful waiting in this study is far more high risk than most patients diagnosed in contemporary series. In fact, the cohort series of conservative management in the US are largely populated with screening-detected, low-risk, low-volume prostate cancer, with characteristics suggestive of indolent disease [6].

Moreover, the trend in conservative management of low-risk clinically localized prostate cancer is toward surveillance and away from watchful waiting. In active surveillance, the aim is to spare the patient the morbidity of treatment until or unless signs of progression are detected in a fairly rigorous surveillance protocol. At that point, treatment with curative intent is initiated. By contrast, the aim of watchful waiting is to intervene with systemic palliative therapy if symptoms of advanced disease arise. Thus, while the Scandinavian study demonstrates a survival advantage for surgery over watchful waiting in a mixed population of men with prostate cancer, it remains unclear whether surgery offers advantages over active surveillance in a screening-detected population of low-risk prostate cancer patients.

The only other RCT comparing radical prostatectomy with watchful waiting was performed by the Veterans Administration Co-operative Urological Research Group (VACURG) and was reported by Iversen et al. [5]. This was a very small study, involving only 142 patients, 66 of whom had palpable disease. After 23 years of follow-up, there was no significant difference in overall survival between groups. Not surprisingly, age and grade were strongly predictive of overall mortality. As the authors point out, it is difficult to draw conclusions with regard to the efficacy of surgery compared to watchful waiting in light of the “lack of statistical power and methodological flaws.”

Population-based observational studies

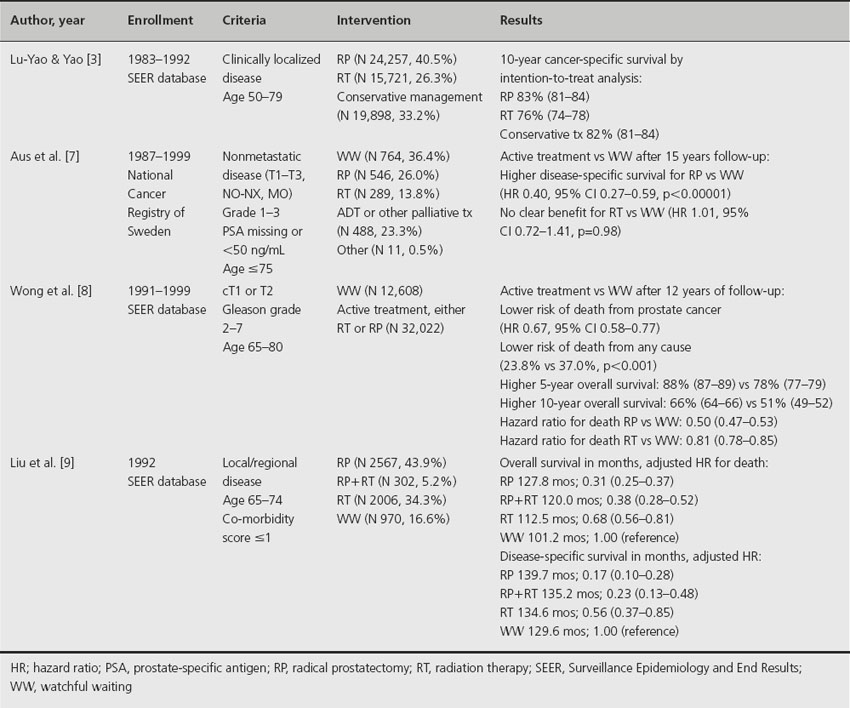

There are a number of population-based observational studies that demonstrate a survival advantage for surgery over conservative management of prostate cancer (Table 27.2) [3,7–9]. One of these studies failed to demonstrate an advantage for active treatments over conservative management [3]. The authors hypothesize that their appropriate use of an intention-to-treat analysis (whereby patients who had aborted prostatectomies after the discovery of positive lymph nodes were grouped with patients who had completed prostatectomies) evened the playing field for comparisons with other treatments in which lymph nodes are evaluated only by clinical means. This point is valid, as using a treatment-received approach would tend to enrich the prostatectomy group with lower risk men and those with advanced disease would end up in the observation group. However, other studies, such as that by Wong et al. [8], demonstrate a survival advantage for surgery in a low-risk population, a group with a very low likelihood of aborted prostatectomy due to positive nodes.

Table 27.2 Population-based observational studies comparing watchful waiting with surgery for management of clinically localized prostate cancer

Taken in their entirety, this group of population-based observational studies is highly suggestive of a disease-specific survival advantage for patients undergoing surgery for treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer compared to men managed conservatively. Two of the studies actually demonstrate an overall survival advantage for patients managed surgically [8,9].

Other studies

Several groups have undertaken meta-analyses of this topic. One from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality was published recently and drew heavily on an earlier effort by the American Urological Association [10,11]. These meta-analyses point out the paucity of high-quality evidence on which to base treatment decisions among the various management options.

There are numerous case series that describe single-institution or multi-institution experiences and pooled analyses looking at either surgery or observation [6,12–20]. While each option can be shown to have excellent long-term disease-specific survival in appropriately selected patients, these studies are not particularly useful in comparing the two management strategies. For the most part, these studies are considered low-grade evidence.

There are two nonrandomized, retrospective case–control series comparing immediate surgery to delayed surgery [21,22]. In one, a group of 38 men who were enrolled in an active surveillance protocol at Johns Hopkins went on to have delayed surgery at a median of 26.5 months after diagnosis [21]. Their pathological outcomes were compared with 150 patients with matched baseline clinical characteristics. Each group had a similar likelihood of adverse pathological findings. The other study of this type looked at 865 men with low-risk prostate cancer and examined the impact of the time between biopsy and surgery on the risk of biochemical progression [22]. The authors found no difference in the likelihood of biochemical progression between patients who delayed surgery for between 90 and 180 days compared to those who had surgery in less than 90 days (multivariable adjusted relative risk (RR) 1.10, 95% CI 0.70–1.71). However, they did find a significant trend when they included patients who delayed surgery for more than 180 days (multivariable adjusted RR 2.73, 95% CI 1.51–4.94, p = 0.002).

Comment

There is a striking paucity of high-quality evidence to help patients and clinicians determine the optimal management strategy for an individual patient with clinically localized prostate cancer. The best available evidence comes from one high-quality RCT, one underpowered RCT and a number of large population-based observational studies. Thus, by GRADE criteria, the evidence is moderate grade [23]. In comparing radical prostatectomy with watchful waiting for the treatment of clinically localized disease, the data show that patients treated with surgery have a small but measurable advantage in terms of local control, prevention of distant metastases, disease-specific survival and overall survival. This advantage may come at the cost of surgical morbidity, which must be factored into treatment decisions. The difference in survival advantage also appears to be most pronounced among younger patients in whom follow-up of a decade or more may be required before differences become apparent. In a quality of life study that accompanied the Scandinavian randomized trial, patients undergoing surgery experienced increased rates of erectile dysfunction and incontinence, but overall sense of well-being and subjective quality of life were comparable to patients on watchful waiting at a median of 4 years [24].

Implications for practice

Although radical prostatectomy appears to confer a survival advantage over watchful waiting according to one RCT and several population-based observational studies, the data are inconclusive and cannot be uniformly applied. Many factors, including patient age, risk category, patient preferences and expected morbidity of treatment, play into the decision of how to manage clinically localized prostate cancer. In the absence of a uniform consensus, the updated 2007 American Urological Association (AUA) guideline considers discussion of surgery, radiation, brachytherapy and watchful waiting as a standard [11]. The Panel also set a standard of informing the patient of the superiority of surgery compared to watchful waiting, based on the outcome of the Scandinavian randomized trial. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines are similar, except that they do not recommend observation for intermediate-risk patients with a longer than 10-year life expectancy and high-risk patients with a longer than 5-year life expectancy [25]. European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines call for watchful waiting and surgery as reasonable treatments for most asymptomatic men with nonmetastatic disease [26].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree