Fig. 19.1

CT 3-dimensional system to evaluate pattern of recurrence (With kind permission from Springer Science + Business Media: Höcht et al. [21], p. 110)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more effective than CT in detecting and staging local recurrence [22]. An MRI should be done to ascertain the extent of pelvic sidewall involvement, sacral involvement, and involvement of the major pelvic nerves, all very important elements to take into account during the surgical planning. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging (DW-MRI) is a promising technique for detecting small-volume tumor, and preliminary data indicates that it accurately delineates pelvic recurrence (Figs. 19.2 and 19.3) [22].

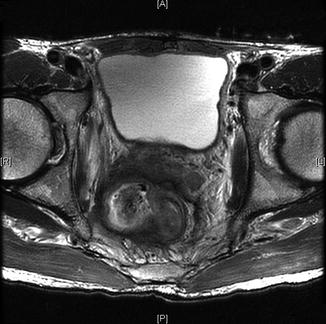

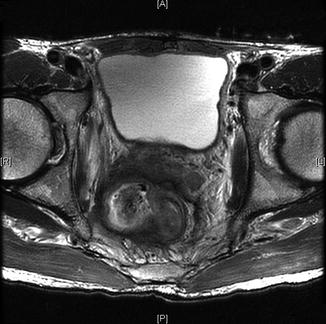

Fig. 19.2

Advanced pelvic recurrence with invasion of seminal vesicles, lateral sidewall, obturator internus muscle

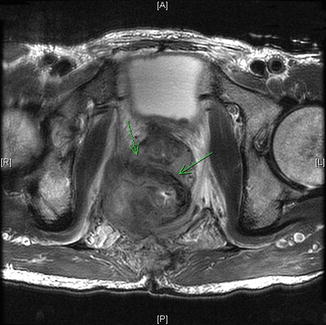

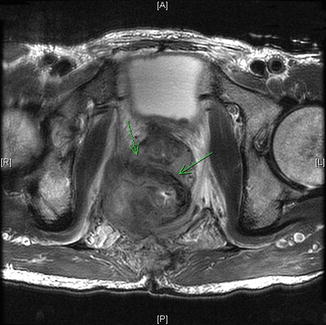

Fig. 19.3

Rectal recurrence with arrows invasion of pelvic sidewall and prostate

Endorectal ultrasound is another imaging modality that can be performed at the bedside and can be helpful in diagnosing recurrent disease in certain circumstances. It is most beneficial when the disease recurs after a local excision. However, the utility of ERUS is limited after a TME because it provides little information regarding the extent of the disease and cannot assess tumor resectability [23].

On many occasions, it is difficult to identify local recurrences using conventional imaging modalities, due to an inability to distinguish between surgical changes, tumor recurrence, or benign lesions. Under these circumstances, positron emission tomography (PET)/CT plays a key role in diagnosing rectal cancer recurrence. This imaging modality entails use of the glucose analog fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), a marker of the enhanced glucolytic activity characteristic of cancer cells, as well as the anatomical resolution of the CT scan. FDG-PET CT offers the opportunity to localize small lesions by detecting small increases in the metabolic activity in areas or organs that, on conventional imaging, appear to be negative. Such findings lead to modification of therapeutic interventions. On the other hand, if the results of conventional imaging are equivocal, PET/CT may be useful for confirming or excluding metastatic disease, and investigating an otherwise inexplicable elevation of CEA. A recent meta-analysis comparing FDG-PET, FDG-PET/CT, CT, and MRI in the detection of recurrent colorectal cancer in patients with high suspicion of recurrent disease, based on symptoms or elevated CEA, suggested that FDG-PET and FDG-PET/CT performed more accurately than CT scan alone. PET/CT also demonstrated greater accuracy than MRI in identification of lymph node recurrence in a lesion levels analysis [22]. In another meta-analysis, FDG-PET without CT scan showed an overall sensitivity of 97 % and a specificity of 76 %. These findings led to changes in the management of 29–40 % of patients initially diagnosed with tumor recurrence. This imaging modality also proved to be cost-effective [24]. However, despite the advantages of FDG-PET, its accuracy depends on tumor size and FDG uptake. Lesions measuring less than 1 cm in diameter are more difficult to detect with PET scanning, as are mucinous tumors (which have poor FDG uptake). Finally, FDG-PET cannot be used to detect or evaluate local recurrence if there is residual inflammation of the tumor bed secondary to chronic leaks.

Regardless of the imaging studies used to help diagnose a local recurrence, histologic confirmation is imperative. In the setting of an extraluminal recurrence the biopsy can be done percutaneously, under radiological (CT) guidance; in the setting of intraluminal or anastomotic recurrence, biopsy can be obtained endoscopically.

Delineating the precise location of a local recurrence is important when assessing the feasibility of surgical resection. While there is no standardized approach to categorizing recurrence by location, several groups have proposed classification systems (Table 19.1). Yamada and colleagues described three different patterns of invasion: localized (recurrence into adjacent organs or connective tissue), sacral, and lateral (sidewall invasion). In this study the 5-year survival was 38 % for localized tumors, 10 % for sacral tumors, and 0 % for laterally invasive tumors [28]. A group at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center has described a nomenclature based on anatomical location of tumor within the pelvis, defining recurrence as either axial (anastomotic, mesorectal or perirectal soft tissue, or perineum); anterior (involving the genitourinary tract); or posterior (involving the sacrum and presacral fascia, and the lateral bony pelvis) [27]. The Mayo Clinic bases its classification system on degree of fixation, while also considering factors such as sites of fixation and invasion (Fig. 19.4) [26]. Wanebo and colleagues have proposed a system utilizing the TNM model: TR1–TR5, in parallel to TNM staging [25]. All of these classification systems have advantages and drawbacks, but their heterogeneity makes it difficult to compare outcomes and methodology.

Table 19.1

Proposed classification systems for locally recurrent rectal cancer

Authors/Institution | Classification | Description |

|---|---|---|

Wanebo et al. [29] | TR1 or TR2 | Intraluminal local recurrence at the primary resection site following local excision or at the anastomosis site |

TR3 | Anastomotic recurrence with full thickness penetration beyond the bowel wall and into the perirectal fat | |

TR4 | Invasion into adjacent organs, including the vagina, uterus, prostate, bladder and seminal vesicles, or into presacral tissues with tethering but not fixation | |

TR5 | Invasion into bony ligamentous pelvis, including the sacrum, low pelvis, side walls or sacrotuberous/ischial ligaments | |

Mayo Clinic [25] | F0–F3 | Degree of fixation both in terms of site (anterior, sacral, right or left, and number of points of fixation) |

Memorial Sloan Kettering [26] | Anterior | Anastomotic, mesorectal or perirectal soft tissue, or perineum following abdominoperineal excision of rectum |

Posterior | Genitourinary tract, including the bladder, vagina, uterus, seminal vesicles and prostate. | |

Lateral | Sacrum and presacral fascia | |

Axial | Soft tissue of the pelvic sidewall and lateral bony pelvis. | |

Yamada [27] | Localized | Adjacent organs or connective tissue |

Sacral | Invades S3, S4, S5, Coccyx and periosteum | |

Lateral | Invades sciatic nerve, greater sciatic foramen, side wall and upper sacrum S1. |

Fig. 19.4

Mayo Clinic classification of pelvic recurrence 1996. f0 no fixation, f1 fixation in one area (red line), f2 fixation in two areas, f3 fixation in three areas (From Ferenschild et al. [30])

Treatment Approach

When rectal cancer recurs in the pelvis, several important issues should be discussed and reviewed before proceeding with surgery. It is best if these decisions are discussed in a multidisciplinary setting, since treatment of the patient with pelvic recurrence will often involve colorectal surgical oncologists, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, and other specialists. The questions that must be answered are as follows: (1) Is there any evidence of distant metastases? If the answer is yes, surgery for the rectal recurrence will not be curative. (2) Is the recurrence resectable? (3) Has the patient received chemotherapy and radiation prior to recurring? If the answer is yes, will the patient benefit from additional therapy before proceeding to surgery? Furthermore, if the patient has already received radiation, has he or she received the maximum allowable dose? (4) If the tumor is not resectable, will the patient benefit from palliative surgery?

Preoperative Treatment

The goal of preoperative treatment is to downsize the recurrent tumor, increasing the possibility of re-resection with negative margins. Therefore, the initial evaluation is an assessment of tumor resectability. In patients with a resectable tumor who did not receive neoadjuvant chemoradiation during treatment of their primary tumor, preoperative combined modality therapy should be delivered in order to increase the possibility of achieving negative surgical margins [29]. Patients who have had a full dose of external beam radiotherapy in the past are generally not candidates for additional radiation. If the patient has received less than 50.4 Gy, however, a modified dose is sometimes given. Some centers advocate additional radiation doses of up to 30.6 Gy, with or without sensitizing chemotherapy, in patients previously treated with 50.4 Gy [29]. Some locally recurrent colorectal cancers do respond to chemotherapy, and aggressive chemotherapy without radiation may be a treatment option for some. The literature on this topic is sparse, and currently there is no definitive consensus regarding chemotherapy for locally recurrent rectal cancer. Hu et al. found that combining FOLFOX with radiotherapy provided better survival than radiotherapy alone in patients with locally recurrent rectal cancer [31]. Following preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, re-staging should be done to exclude interim development of distant metastasis and ascertain the extent of the local recurrence. Clinical work-up should also evaluate the recurrent tumor’s degree of fixation. For patients with unresectable disease, palliative treatment aimed at alleviating symptoms and improving quality of life should be discussed.

Surgical Considerations

Radical surgery that achieves negative margins is the only potentially curative option for patients with local recurrence. Without surgical intervention, locally recurrent rectal cancer carries a dismal prognosis: median survival is typically 6–7 months [32]. Surgical planning involves determining what type of surgery will be performed, based on the anatomic feasibility of achieving an R0 resection, estimation of acceptable risk for short- and long-term complications, impact on quality of life, and mortality risk (Fig. 19.5). Rigorous preoperative assessment of the patient’s fitness for undergoing such a major operation is crucial [33]. A patient who is generally healthy (ASA I–III, no evidence of metastatic disease) may be considered for potentially curative resection. Patients with poor status (ASA IV-V) are not candidates for the extensive surgery that is normally required. Proper evaluation and risk assessment should include identification of any findings that would contraindicate re-resection. When assessing a locoregional recurrence, the first step is to exclude peritoneal disease. This is often missed during preoperative imaging and evaluation. Patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis are considered to have metastatic disease. These patients require a different treatment approach, which may include cytoreductive surgery, intraperitoneal chemotherapy, or palliative surgery, such as a colostomy, if the tumor cannot be adequately cyto-reduced.

Fig. 19.5

Circumferential margins and planes of dissection. dotted lines represent circumferential resection margins/planes of resection, S3 indicates level

The presence of metastatic disease (except in the case of isolated resectable metastases), sciatic pain, bone or nerve involvement by tumor, and hydronephrosis generally preclude resection. Lower limb edema, secondary to lymphatic or venous obstruction of the external iliacs, is an ominous sign of extensive disease and is considered an absolute contraindication to surgery. Encasement of the common or external iliac vessels, bilateral ureteral obstruction, or circumferential involvement of the pelvic wall by tumor, indicate a low probability of obtaining negative margins. Unilateral involvement of the internal iliac vessels may be compatible with an R0 resection in selected cases. Tumors involving the iliac vessels and ureters may also invade bony structures, such as the sacrum. Sacral invasion above the S1–S2 juncture almost invariably requires that the patient undergo internal fixation, secondary to sacroiliac instability. Some centers consider that sacral invasion above S2 contraindicates surgery. Prognostic factors should be taken into consideration. Patients who are deemed physically fit enough to withstand the rigors of the planned surgery must also be evaluated psychologically, and counseled regarding the potential impact of an extensive radical re-resection on their postoperative function and quality of life.

In up to 50 % of cases, recurrence is confined to the pelvis and theoretically amenable to cure [34, 35]. Unfortunately, due to the daunting complexity and morbidity associated with these procedures, many patients who may be resectable at the time of diagnosis are not offered surgery as an option. Consequently, they are often referred to a tertiary care center for surgical evaluation much later, when the recurrent tumor has progressed and is, in fact, unresectable.

At our institution we offer resection of locally recurrent rectal cancer in patients in whom resection with negative margins can be achieved. Total pelvic exenteration—with or without sacrectomy—can be performed in carefully selected patients. While this extensive procedure can afford prolonged survival in properly selected patients, it is an extensive operation entailing considerable morbidity.

During resection for a rectal recurrence, non-standard planes of dissection must be utilized; this is due to the recurrence and the previous dissection along standard anatomical surgical planes [36]. It is difficult to distinguish between scar tissue and recurrent tumor, and the planes that were opened during the initial surgery may now be affected by tumor. Therefore, the surgeon should be prepared to perform a wide resection through uninvolved planes. Pelvic structures such as ureters and blood vessels may be displaced due to previous surgery, cancer recurrence, or scar tissue. Ureters are often located more medially in patients who have had previous surgery [37]. The plane of dissection should be lateral to the endopelvic fascia, so as to ensure that all previously dissected planes are included within the specimen, and any remaining fascia propria should be included within the surgical specimen [36]. This may involve resection of neighboring anatomic structures and organs (Fig. 19.4) [13, 38]. The majority of patients require an en bloc resection of adjacent anatomy such as the abdominal wall, bladder, pancreas, and duodenum; and the uterus and ovaries in female patients [38]. Finally, the pelvic dissection should be lateral to the levators [25].

Surgery and Location of Recurrence

Centrally located pelvic recurrences are often treated with either a low anterior resection (LAR) or APR. Anterior recurrences attached to the genitalia or the urologic organs usually require a complete pelvic exenteration (Figs. 19.6 and 19.7) [39]. Posterior recurrences adjacent to the sacrum can be treated with a partial sacrectomy, preferably below the level of S3 [25]. Lateral recurrences involving the pelvic sidewall and sciatic notch are difficult to resect with negative margins. As a general rule, a recurrent tumor is rarely resectable if the fat plane medial to the obturator internus is obliterated. Invasion of the sacrum (above the level of S2) and invasion of the pelvic sidewall nearly always preclude surgery (Figs. 19.8 and 19.9).

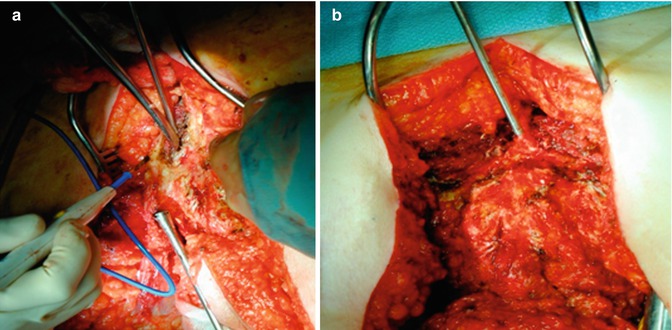

Fig. 19.7

Pelvic exenteration: perineal phase. A anterior plane of dissection; B posterior plane of dissection [56]

Fig. 19.8

Vascular nerves and muscle planes during lateral dissection (Modified from Austin and Solomon [40])

Fig. 19.9

Pelvic view and structures involved with posterior and lateral recurrence (Modified from Austin and Solomon [40])

In anterior recurrences the urinary system is often involved, requiring resection of the ureters and possibly the bladder, as well as the prostate and/or seminal vesicles in male patients [18, 41]. Some cases require extensive perineal resection and reconstruction with tissue flaps [42], usually a rectus abdominus or a gluteal advancement flap. Posterior recurrences may involve the sacrum and require sacral resection, with control of the dural sac and sacral nerves. Ideally, treatment of patients with locally recurrent rectal cancer will involve a multidisciplinary team of specialists including medical and radiation oncologists, colorectal surgical oncologists, urologic surgeons, plastic and reconstructive surgeons, orthopedic surgeons, vascular surgeons, and possibly neurologic surgeons. Operations for locally recurrent rectal cancer are generally lengthy, with extensive blood loss and large fluid shifts. A thorough and complete preoperative evaluation by the anesthesia team is paramount (Figs. 19.10, 19.11, and 19.12).

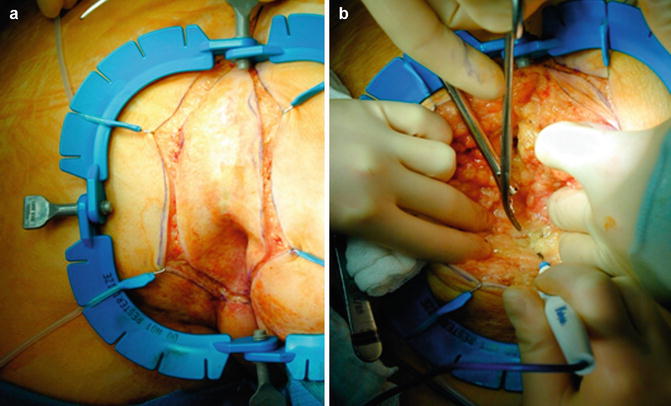

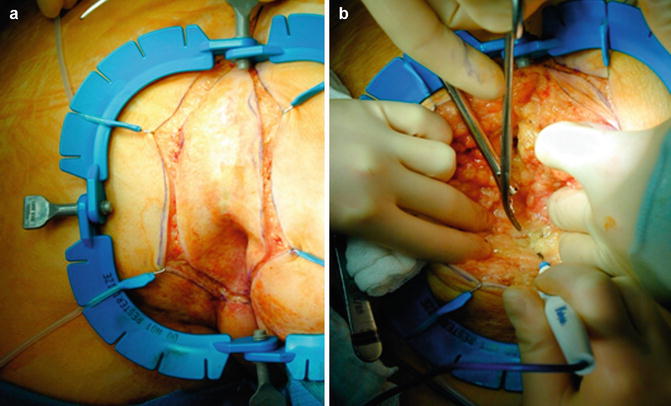

Fig. 19.10

(a) Perineal dissection – incision; (b) Dissection ischiorectal fat