2 Queen’s University Belfast, UK

3 Manchester Business School, The University of Manchester, UK

Introduction

It is estimated that 9% of the English adult population have chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages 3–5. Within this group there is a disproportionate number of older patients, many of whom have other chronic conditions, and there is a 4% risk of reaching stage 5 CKD. Most patients with CKD die from other conditions, usually vascular, but a proportion will die from progressive kidney disease, and a significant number of dialysis-dependent patients will die following a decision to withdraw from dialysis. A growing cohort of palliative patients are those who have advanced CKD, both progressive and stable, who are clinically unsuitable for dialysis, or who have chosen not to have it. The key to providing effective supportive and palliative care to people with CKD is in pre-emptively identifying those likely to need it and ensuring that appropriate systems are in place to meet individual needs as required. Part of this challenge is the heterogeneity of health states in patients with CKD and the uncertainty in patterns of chronic illness progression. The purpose of this chapter is to assist in the identification and management of patients with chronic kidney disease approaching the terminal phase of their lives. It includes references to evidence-based guidelines and pathways of care aimed at the practical organisation and coordination of care as well as symptom management.

Background

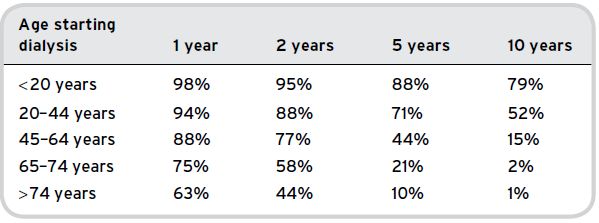

Around 45 000 people receive renal replacement therapy (RRT) in the UK, of whom just under half have a kidney transplant and the rest are on dialysis. Most are older adults and have at least one other chronic condition. Consequently mortality in this population is high, and patients receiving dialysis have a much shorter life expectancy than a comparable age group in the general population. As Table 10.1 shows, the chance of surviving 1–10 years on dialysis is age-dependent.

Chronic kidney disease is a life-limiting illness, but nonetheless most patients die from other causes. Table 10.2 illustrates the commonest causes of death in patients with kidney disease.

Approximately 15% of older patients opt for a non-dialytic care pathway. These people tend to be those with multiple chronic conditions who may already be frail and require a high degree of health and social support. The evidence to date suggests that for patients starting dialysis in similar health states, dialysis confers no additional benefit in terms of longevity and can often incur a significant burden affecting the patient’s quality of life. The aim of management is to ensure that patients receive the appropriate care and support irrespective of where that is delivered. This requires a regular assessment of need, ongoing discussions with patients and their families, supported decision making and coordination across care providers.

Table 10.1 Percentage chance of surviving 1, 2, 5 and 10 years following commencement of dialysis, depending on the age the patient at start of dialysis (Modified from Stein & Wild 2002).

Table 10.2 Common causes of death in patients with CKD (Modified from Stein & Wild 2002).

| Dialysis patients | Transplant patients | |

| Heart disease | 42% | 30% |

| Infections | 15% | 12% |

| Strokes | 12% | 12% |

| Treatment withdrawn | 18% | 3% |

| Cancer | 6% | 34% |

| Other | 6% | 9% |

Identifying patients with CKD approaching the end of life

As with other chronic conditions, identifying when a patient with advanced kidney disease is approaching the end of life can be difficult to predict, as the trajectory is often non-linear and can be complicated by inter-current illness or the extent of other chronic conditions. The Gold Standards Framework (Thomas 2003) is a useful aid for identifying people who are likely to require palliative care. It includes two general triggers for palliative care and some condition-specific indicators for CKD. The surprise question – ‘Would I be surprised if this patient were to die within the next 6–12 months?’ – is an intuitive one which draws on the experience of the practitioner and their knowledge of the patient and their circumstances. If the answer to the question is no, it provides an impetus to initiate a number of activities depending on the likely prognosis and the anticipated time frame. The second trigger occurs when a patient expresses a wish to stop ‘curative’ treatment. The third trigger refers to kidney-specific indicators of advanced disease and includes patients with stage 4 or 5 CKD whose condition is deteriorating with at least two of the following indicators:

- blood results indicating that the patient would normally require dialysis, or blood results on dialysis that are consistently suboptimal

- weight loss of more than 10% in 6 months

- hypoalbuminaemia (< 24 g/L)

- complex symptoms that are difficult to control

- requires assistance with mobilising, e.g. walking frame, and in bed for ≥ 50% of the time

- two or more non-elective admissions in previous three months

- patient has expressed a desire to stop treatment

In addition, certain stages in the patient’s care pathway can trigger professionals to review a patient’s palliative care needs:

- at time of decision for conservative kidney management

- around decision to withdraw from dialysis

- deteriorating despite dialysis

- time of crisis, e.g. stroke, malignancy

- other life threatening condition, e.g. malignancy

- changing renal replacement modalities due to access failure or ineffective clearance, including a failing transplant

Managing care

For the purposes of organising health care, patients approaching the end of their lives with kidney disease can be broadly divided into three categories – those who:

Decision support

Even in patients with advanced kidney disease, it is important to remember that acute decline may not be due to their kidney injury and may potentially be reversible, depending on the cause. Possible interventions must be considered in light of the patient’s general condition prior to any acute illness, as well as their capacity to benefit. This is not always obvious in chronic illness and sometimes requires a ‘leap of faith’ with circumscribed parameters (specialists are more experienced in this approach). About a quarter of patients receiving RRT will choose to withdraw from dialysis, and most will die within 2–4 weeks of dialysis being stopped. These patients should be given the opportunity to talk through their situation and their reasons for wishing to stop dialysis. This is best done with their specialist team, who are likely to know them well. Ideally, discussions should occur over a period of time during which options can be discussed and re-discussed, giving the patient the time to share their thoughts and any decisions with their immediate family. Professionals may need to facilitate these discussions with the family, and will also need time to establish the patient’s needs and wishes, which the patient may not always be able to articulate. Patients with cognitive impairment are sometimes not in a position to decide for themselves whether to withdraw from dialysis; however, multidisciplinary specialist teams are often ideally placed to recognise the clinical or global deterioration and a reduction in quality of life of these people. They will often initiate discussions with the patient’s family and advise about prognosis. The point at which the benefits of dialysis are likely outweighed by the physical, psychological and social burden of the treatment is particular to each individual, and should be discussed appropriately with the patient and his or her family.

The focus of care at this stage will move towards symptom control and keeping the patient comfortable. Psychological, social and spiritual needs should be reviewed at regular intervals, and specialist services often include this as part of their multidisciplinary working. In situations where it is obvious that the patient’s condition is terminal or the clinician considers it to be, it is important to ensure that the prognosis is shared with the patient and the family. Often this requires the clinician to be explicit in ensuring that the patient and the family understand the gravity of the situation. In patients with CKD the illness trajectory is often characterised by episodes of acute illness and/or deterioration and periods where the patient may be relatively well and stable. It is often difficult during the times of acute illness to know whether the patient will recover from it, particularly if they have recovered from similar episodes before. In situations of uncertainty, it is often necessary to reiterate the possibility that the patient may not recover, and that if they do, they may not be as well as they were before the acute episode. These conversations can help the patient and their family to plan for different eventualities, and can encourage them to articulate their anxieties and needs for which support can be provided.

Terminology

End-of-life care

This is a broad term that identifies more than the phase immediately prior to death. It may be difficult to identify when a patient is at the beginning of this phase, and patient, carer and professional perspectives are likely to differ. This phase is variable and may last for weeks or months. The presence of other acute or chronic conditions can impact on the rate at which kidney function declines. Recognising that a person is entering this phase enables the supportive and palliative care needs of both the patient and the family to be assessed and organised through to the last phase of life and into bereavement. Care should be taken to ensure that the patient and family are aware of, and understand, the likely prognosis. In situations where uncertainties exist around the illness trajectory and time lines, this should be conveyed to the patient and family as appropriate. A common complaint amongst bereaved relatives is that they were unaware of the possibility that the patient could die. Whilst it is sometimes difficult to be accurate over timings, in patients who continue to deteriorate despite appropriate interventions it is important to check with the patient and the family their understanding of the situation and possible outcomes. Most dying patients appreciate the opportunity to make arrangements and put their affairs in order.

Supportive care

Supportive care can be described as care that ‘helps the patient and their family to cope with their condition and treatment of it – from pre-diagnosis, through the process of diagnosis and treatment, to cure, continuing illness or death and into bereavement. It helps the patient to maximise the benefits of treatment and to live as well as possible with the effects of the disease. It is given equal priority alongside diagnosis and treatment’ (National Council for Palliative Care 2012).

Palliative care

Palliative care is the active holistic care of patients with an advanced and progressive illness. The key aim of palliative care is to deliver the best quality of care to patients by managing any symptoms and providing psychological, social and spiritual support. Palliative care also incorporates the principles of supportive care, and the terms are often used synonymously.

Conservative management

Conservative management (CM) refers to the treatment of advanced kidney disease without dialysis. This includes interventions to slow down or arrest any deterioration of kidney function and to minimise associated complications. Approximately 15–20% of patients with stage 5 CKD will opt for non-dialytic treatment and will be managed on a CM pathway (Murtagh & Sheerin 2010). CM may be the most suitable option for frail patients who already experience a high disease burden and functional decline. For this cohort of patients, the rigours of dialysis and the associated restrictions on daily life can often outweigh any perceived benefits of dialysis. As yet, there is no convincing evidence to suggest that, in older, frail patients, who may have other chronic conditions and general functional impairment, dialysis confers any additional benefit above CM in terms of longevity and quality of care. CM can also be an appropriate option for patients with a kidney transplant whose function is deteriorating and who are clinically unsuitable for, or unwilling to undertake, dialysis or a further transplant. There will also be a group of patients with functioning transplants who are dying from other conditions in which their kidney condition is not considered an issue.

A large proportion of people with CKD experience other, linked, conditions, and this proportion increases with age. The complications of CKD include:

- cardiovascular disease

- mineral and bone disorders (e.g. calcium and phosphate disorders)

- anaemia

- malnutrition

- depression

- increased risk of other non-cardiovascular disease, e.g. infection and cancer

- increased risk of fracture

The relationship between cardiovascular disease and CKD is strong and increases with age. Kidney function in many elderly patients with CKD remains stable, and most will die from cardiovascular events rather than progressing to advanced kidney disease. The impact of additional chronic conditions and general wellbeing may play an important role in patients deciding on their future treatment and whether they are likely to be offered dialysis.

Patient population

People dying with or from kidney disease can be broadly divided into three main groups. The purpose of defining these groups is to anticipate the general trajectory of decline and to ensure services are in place to meet their needs. The three groups will generally be under the care of specialist services, although there are always exceptions, and irrespective of where the patient is treated, renal services encourage enquiries from those managing patients with CKD in other services:

Deciding whether to dialyse or not – a supported decision

Patients with CKD require timely information regarding their prognosis and treatment options in order to make a decision on their preferred treatment pathway. Discussions around treatment modalities should be initiated around a year before the patient requires dialysis. Patients reviewed in the CKD service have usually been attending the clinic for many years. This allows a therapeutic relationship to develop between the patient and the CKD multidisciplinary team and assists the team in anticipating when RRT will be required and when it is appropriate to commence discussions around treatment options.

Determining when a patient will require RRT relies heavily on the clinical knowledge and skills of the specialist team in predicting the rate at which the patient’s renal function is declining. The rate of decline is influenced by many factors, including the primary cause of kidney impairment and any infections or related illnesses. The patient’s estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is an arbitrary marker of when to start dialysis, and whilst historically a level of 15 or less was generally used as an indicator, the growing body of evidence from CM clinics suggests that many patients, particularly older ones, can tolerate much lower levels and remain relatively symptom-free.

Decision making around CM is both challenging and difficult and is likely to become more so, as increasing numbers of people survive into old age with the associated increase in the prevalence of chronic conditions. Palliative and supportive components of care are becoming increasingly important in the overall care of the older patient with CKD, who often has limited life expectancy and a high symptom burden. Discussions and any decisions should be carefully documented in the patient record and shared with appropriate stakeholders such as the general practitioner (GP). With the patient’s consent, the patient’s next of kin should be involved in these discussions. They are often an invaluable support to the patient, and it is important that they understand how the decision was reached, i.e. in the best interests of the patient rather than as a resource issue. In frail patients with complex health needs, their kidney function may be less of an issue than, for example, their heart failure. In these situations, dialysis can often hasten death rather than prolong life. In patients who are clinically unsuitable for dialysis and unlikely to benefit it should not be presented as an option. The reasons for this should be explained at an early stage in the process.

Patients who have decided on a CM pathway can sometimes worry that they have made the wrong decision. It is therefore important to provide ongoing support and reassurance to the patient and the family. Although RRT has transformed the prognosis of renal disease, quality of life remains impaired by the disease and there is a significant treatment burden associated with dialysis. Dialysis is a demanding treatment, even for younger and fitter patients. Some will feel that without any corresponding benefit the burden is too much to tolerate.

Patients may choose not to have dialysis for a number of reasons:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree