Figure 2.1 Anatomic compartments of the stomach. Although the stomach can be compartmentalized based on anatomic landmarks, the histologic compartmentalization of the stomach is based on physiologic function. The gastric fundus and corpus (body) are composed of oxyntic mucosa, whereas the pyloric antrum and pylorus contain pyloric glands.

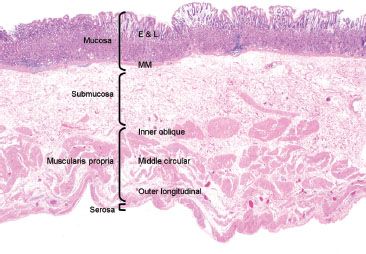

Figure 2.2 Layers of the stomach. This resection specimen illustrates the four main layers of the stomach: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa. The mucosa consists of epithelium (E), lamina propria (L), and muscularis mucosae (MM). The submucosa sits between the muscularis mucosae and the muscularis propria (MP). The MP consists of three muscle layers: the inner oblique, middle circular and outer longitudinal, which function in gastric contraction and peristalsis. The outermost layer is the serosa.

HISTOLOGY AND FUNCTION

Body/Corpus and Fundus (“Oxyntic Mucosa”)

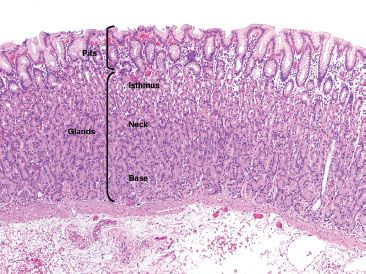

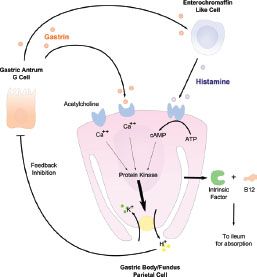

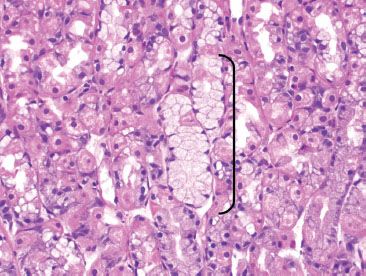

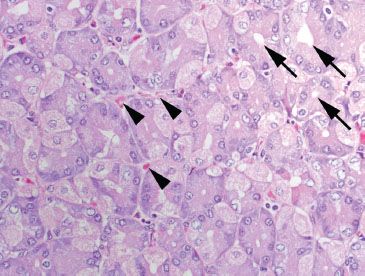

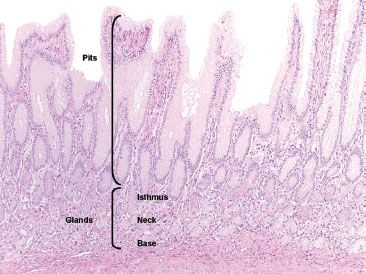

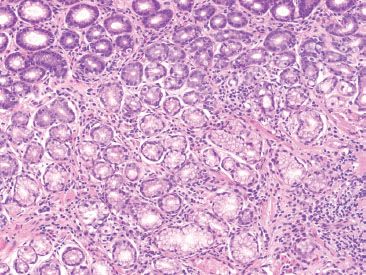

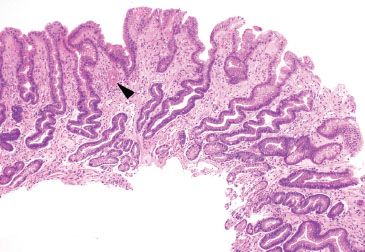

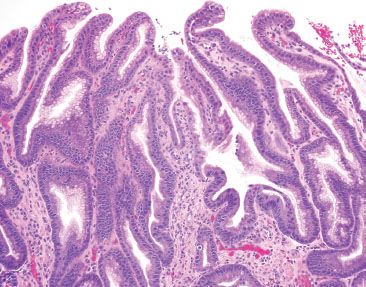

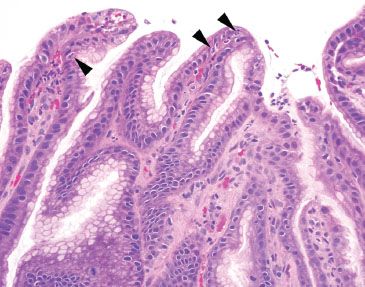

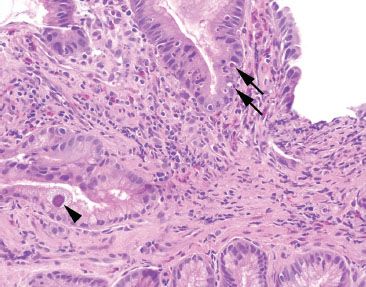

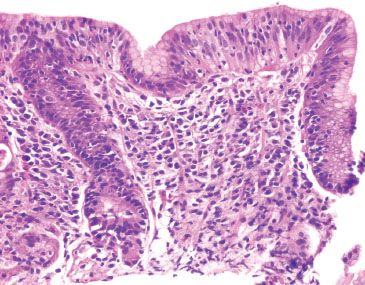

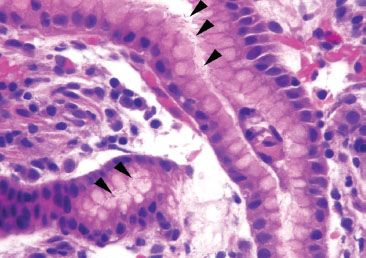

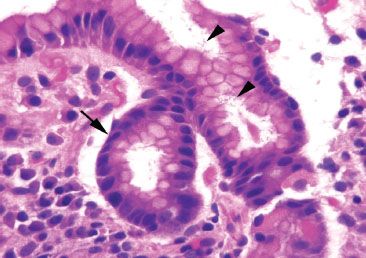

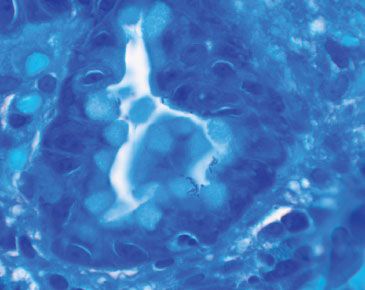

The largest histologic compartment is the gastric body and fundus, comprising 90% of the gastric mucosa (Fig. 2.1). They share similar histology and function as both contain oxyntic (or fundic) glands and have shallow pits that extend less than 25% of the distance to the base (Fig. 2.3). The superficial isthmus contains intensely pink acid-secreting parietal cells that also produce intrinsic factor, important for absorption of vitamin B12 (Fig. 2.4). By comparison, the base of the glands contains bluish-purple pepsinogen-secreting chief cells and scattered enterochromaffin-like (ECL) endocrine cells. The intervening neck area contains a mixture of chief, parietal, and mucus neck cells, the latter of which are important in mucosal regeneration (Figs. 2.5 and 2.6) and should not be mistaken for signet ring cells.

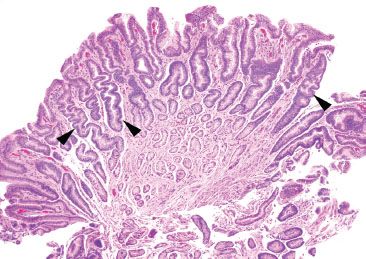

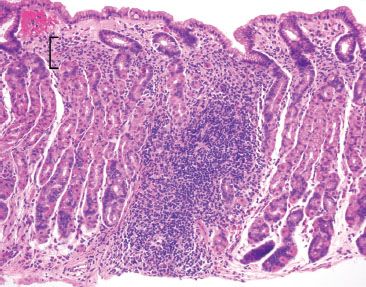

Figure 2.3 Pits and glands in oxyntic mucosa. The gastric pits are lined by foveolar epithelium, a finding that is common throughout the gastric mucosa, independent of site. The deeper glands of the oxyntic mucosa can be divided into (1) the superficial isthmus, composed primarily of the bright pink parietal cells, (2) the transitional neck area, containing a mixture of parietal cells, mucus neck cells, and chief cells, and (3) the base, composed almost entirely of the more basophilic chief cells.

Figure 2.4 Physiology of the parietal cell. The parietal cell has a number of important functions, including production of intrinsic factor (IF) which binds vitamin B12 (cobalamin), thus, allowing the complex to be transported across the small bowel wall. In addition, parietal cells are stimulated to produce acid (H+) by gastrin (produced in the antrum by the “G” cell) and histamine (secreted predominantly in the oxyntic mucosa by ECL cells). Whereas high acid levels inhibit gastrin secretion, conversely, hypoacidic states, such as those with parietal cell atrophy or loss, result in uninhibited secretion of gastrin.

Figure 2.5 Neck of oxyntic glands. There are three cells types within the neck area of the oxyntic glands. The pink parietal cells and the blue chief cells are easily discernible on routine H&E. Harder to appreciate are the mucous neck cells (arc), which are the proliferative stem cell of the gastric glands.

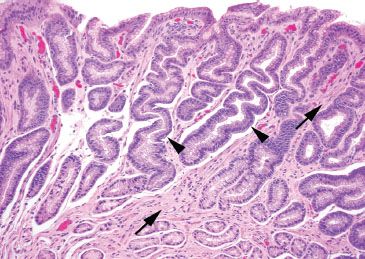

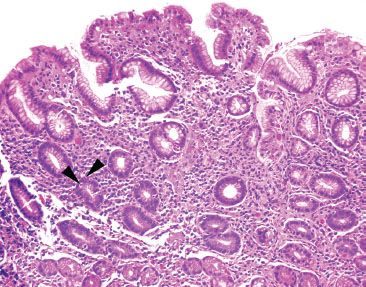

Figure 2.6 Normal oxyntic mucosa cut in cross section. In tissue sections that are oriented tangentially, the oxyntic glands have a mixture of pink parietal and blue chief cells arranged around a central lumen (arrows). Note the abundant capillaries (arrowheads) at the basal aspect of each gland, and the scant lamina propria.

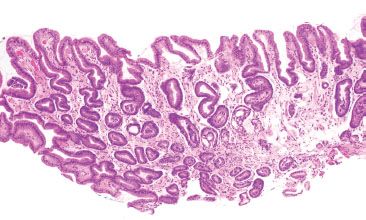

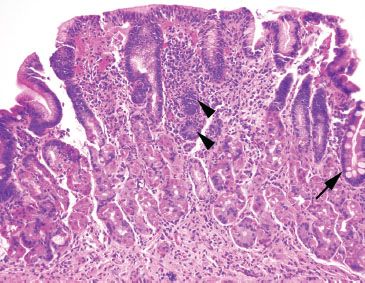

Figure 2.7 Normal antral mucosa. The pits of the antrum are much deeper as compared to the oxyntic mucosa, comprising sometimes greater than 50% of the mucosal thickness. The deeper pyloric glands are composed of mucus secreting cells.

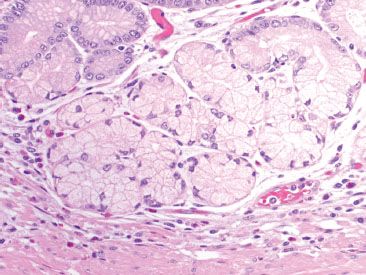

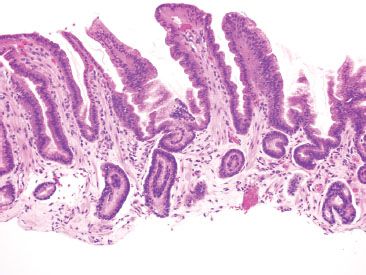

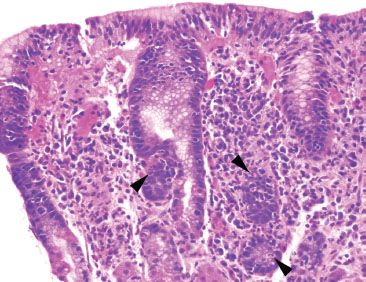

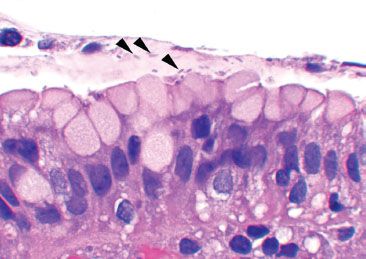

Figure 2.8 Pyloric glands. The pyloric glands are composed of mucus secreting cells with abundant clear foamy cytoplasm and basally located nuclei, which are sometimes flattened, similar to those seen in Brunner glands and the gastric cardia.

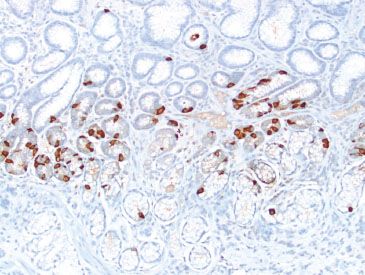

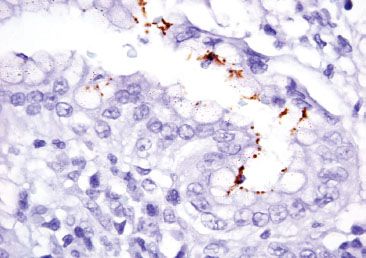

Figure 2.9 G cells (gastrin immunostain). A gastrin immunohistochemical stain highlights a band of G cells, which are exclusively found in the gastric antrum. Their presence can be exploited to identify site of tissue origin.

Antrum and Pylorus (“Antral Mucosa”)

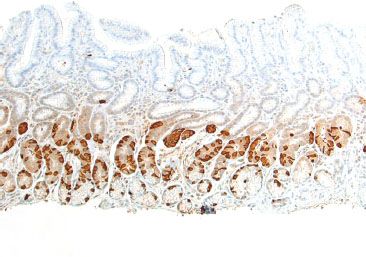

The antrum and pylorus comprise the second largest histologic compartment, and most practitioners regard them as interchangeable, as they are histologically similar (Fig. 2.1). The pits of the gastric antrum comprise approximately 50% of the distance to the base of the glands (Fig. 2.7). Abundant lamina propria separates the purely mucus-secreting tortuous glands of the antral mucosa. These cells have abundant frothy cytoplasm with nuclei that appear flattened against the basal aspect (Fig. 2.8), similar to those seen in Brunner glands and gastric cardiac glands. Importantly, gastrin-producing G cells are exclusively found in the gastric antral glands, and they can be highlighted with a gastrin immunohistochemical stain (Fig. 2.9).

FAQ: Why does my “antrum” biopsy frequently look like oxyntic mucosa?

Answer: More than 90% of the gastric mucosa is oxyntic type, leaving only the distal-most portion of the stomach as true antral-type mucosa. It is not unusual for endoscopists to capture transition zone, or even distal corpus when targeting the gastric antrum.

PEARLS & PITFALLS

By comparison, it would be highly unusual for the endoscopist to miss a targeted biopsy of the body or fundus. If a specimen labeled as “body” or “fundus” shows antral-type histology, consider one of the following scenarios:

• Atrophy of the gastric corpus, such as in autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis

• Mixed specimen or carryover

An immunohistochemical stain for gastrin can be helpful in this scenario by highlighting the antral restricted “G” cells; biopsies from the antrum would have a prominent band of G cells, and those from the body/fundus are nonreactive for gastrin (Figs. 2.10–2.13). See also Chronic Gastritis subsection, this chapter.

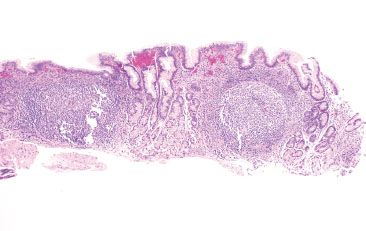

Figure 2.10 Gastric antrum mislabeled as gastric body. This tissue was received in a jar labeled “stomach, body.” There is a complete lack of oxyntic glands, suggesting this tissue likely originated from the gastric antrum.

Figure 2.11 Gastric antrum mislabeled as gastric body (gastrin immunostain). A gastrin stain of the previous figure highlights a band of G cells, confirming the antral origin of this tissue (oxyntic mucosa lacks G cells).

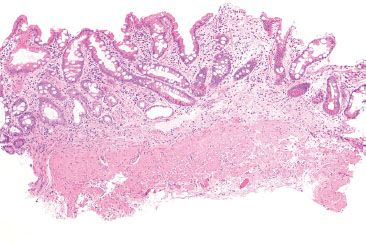

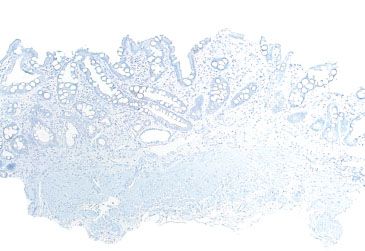

Figure 2.12 Gastric body with total oxyntic gland atrophy. This tissue fragment was received in a jar labeled “stomach, body.” Similar to the previous case (Fig. 2.10), there is a total lack of oxyntic glands. Note the extensive background intestinal metaplasia.

Figure 2.13 Gastric body with total oxyntic gland atrophy (gastrin immunostain). A gastrin stain of the previous figure fails to highlight any G cells, confirming that this biopsy fragment originated from the gastric body or fundus. The total atrophy of oxyntic glands and presence of intestinal metaplasia raises the suspicion for autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis (AMAG). See also Chronic Gastritis, this chapter.

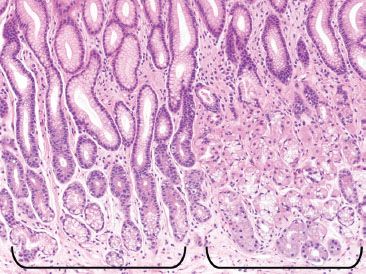

Figure 2.14 Transitional mucosa. The junction of the body and antrum contains a transition zone that includes a mixture of both the clear pyloric glands of the antrum (left bracket), and the mixed pink and blue oxyntic glands of the body (right bracket).

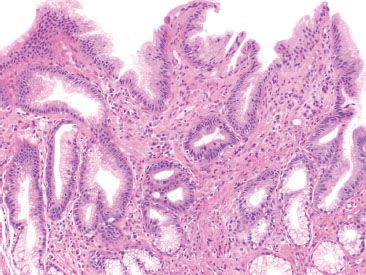

Figure 2.15 Gastric cardia. The gastric cardia is lined by surface foveolar epithelium and the glands are composed of mucous-secreting cells which are histologically identical to those found in the gastric antrum. It is not unusual to see some inflammatory cells in the lamina propria of the gastric cardia.

Transition Zone (“Transitional Mucosa”)

Histologically, the transition between the oxyntic and antral mucosa is gradual, spanning 1 to 2 centimeters. The histology shows mixed glands in varying proportions (Fig. 2.14).

Cardia

The smallest gastric compartment, the gastric cardia, is composed of mucus-secreting cells and is devoid of acid-secreting chief cells and parietal cells. Histologically, the surface epithelium is lined by foveolar cells and the pits and glands are composed of pyloric-type glandular epithelium. In the absence of a biopsy location provided by the endoscopist, the histology is nearly indistinguishable from that of the gastric antrum (Fig. 2.15).

FAQ: Why do my gastric cardia biopsies frequently contain oxyntic mucosa?

Answer: The length of cardiac mucosa is variable. The cardia typically spans only 1 to 4 mm in most adults. It was originally believed that the gastric cardia developed as people aged; however, autopsy studies have disproven this idea, as some infants have cardiac glands and some elderly persons have none, transitioning directly from squamous mucosa to acid-secreting mucosa (Fig. 2.16). Although controversial, the presence of gastric cardiac-type mucosa has also been regarded by some as a purely metaplastic condition secondary to gastroesophageal reflux, Helicobacter infection, and autoimmune gastritis.

PEARLS & PITFALLS

Chronic inflammation is so ubiquitous a finding in the gastric cardia that many practitioners do not mention this finding in their reports; however, the gastric cardiac mucosa may harbor Helicobacter organisms (Fig. 2.17). It is prudent to examine closely or perform staining for Helicobacter organisms in the following scenarios:

• If the pattern of the infiltrate is characteristic of Helicobacter infection; specifically active chronic inflammation, superficial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, and or prominent lymphoid aggregates with well-formed germinal centers, or

• If the inflammation is exuberant and no additional gastric biopsies were obtained from the gastric antrum and body. In this scenario, careful examination of the cardia might be the only opportunity to diagnose an underlying Helicobacter infection.

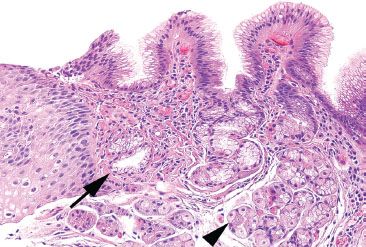

Figure 2.16 Minimal gastric cardia. Seen here is the gastroesophageal junction, with squamous epithelium on the far left, gastric cardiac mucosa composed of a few clear pyloric-like glands (arrow) and an immediate transition into the mixed pink and blue oxyntic glands (arrowhead) of the fundus. The cardia differs from the antrum in lacking G cells.

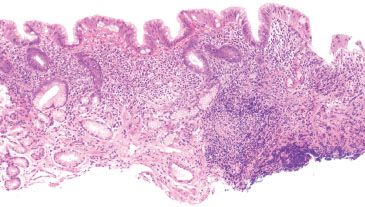

Figure 2.17 Helicobacter pylori carditis. This biopsy of the gastric cardia was performed in evaluation of Barrett esophagus. Although the gastric cardia may have some mild chronic inflammation, the presence of a lymphoid aggregate, expanded lamina propria, and superficial infiltrate should prompt a careful search for Helicobacter organisms. Indeed, Helicobacter organisms were identified on H&E (not shown).

REACTIVE GASTRITIS/GASTROPATHY PATTERN

Figure 2.18 Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern. Reactive gastritis/gastropathy is another example of an entity that is best appreciated at scanning magnification. At low power, the surface epithelium appears dark because of the mucin loss, and it is easy to appreciate the corkscrew-like appearance of the gastric pits (arrowheads). As true for most cases of reactive gastritis/gastropathy, the background inflammation is minimal.

Figure 2.19 Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern. On higher power, the mucin loss is apparent: the surface foveolar epithelium has tiny apical caps of mucin, instead of the normal tall mucin-rich cytoplasm seen in normal apical epithelium. At this power, it is also easy to appreciate the smooth muscle bundles (arrows) between the corkscrew-like gastric pits (arrowheads) which extend toward the surface.

CHECKLIST: Etiologic Considerations for the Reactive Gastritis/Gastropathy Pattern

Bile Reflux

Bile Reflux

Medications

Medications

Alcohol

Alcohol

Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy

Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy

Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia

Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia

Autoimmune Metaplastic Atrophic Gastritis

Autoimmune Metaplastic Atrophic Gastritis

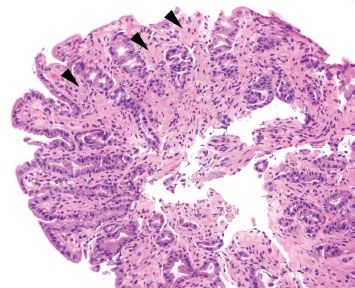

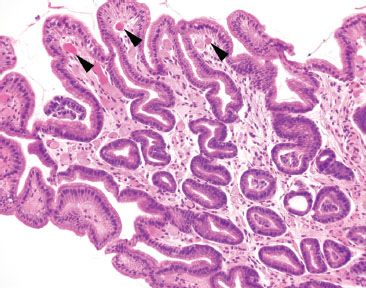

Reactive gastritis/gastropathy constitutes the most common gastric injury pattern (Figs. 2.18 and 2.19). In a recent study of over 500,000 gastric specimens, reactive gastritis/gastropathy was reported in up to 15.6% of cases.15 There is no geographic predilection, and its incidence increases with patient age, seen in only 2% of patients under 10 years and in greater than 20% of patients over 80 years.15 Histologically, this injury pattern refers to foveolar mucin cell depletion, a corkscrew-like appearance of the gastric pits, lamina propria edema, smooth muscle fibers extending between the pits and toward the surface, and little to no inflammation (Figs. 2.20–2.23).

Reactive gastritis/gastropathy is another example of a nonspecific injury pattern. In the majority of cases, no precise etiology can be established.16 Of those with identifiable causes, bile reflux, medications (e.g., NSAIDs), alcohol, portal hypertensive gastropathy, gastric antral vascular ectasia, and autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis have been implicated.15,17–22 Although the etiologic possibilities are broad, the previously mentioned etiologies are thought to induce a chemical-type damage, which result in this characteristic gastric injury pattern. Reactive gastritis is most commonly seen in the gastric antrum, supporting the theory that bile reflux is an important contributing factor. In severe cases, this injury pattern can extend into the oxyntic mucosa, sometimes even involving the cardiac mucosa. These cases must be diligently inspected for dysplasia, intestinal metaplasia, and neoplasia because chronic mucosal injury of any sort can increase a patient’s risk of neoplasia. Specimens should be carefully inspected for congested mucosal vessels (which can be seen with portal hypertensive gastropathy) and thrombosed mucosal vessels, which would suggest a diagnosis of gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE), in the appropriate clinical setting. See also Vascular and Hemorrhagic Injury pattern in this chapter.

Figure 2.20 Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern. Again, the key features of reactive gastritis/gastropathy “jump off the slide” at scanning magnification: gastric surface foveolar mucin cell depletion, a corkscrew-like appearance of the gastric pits, lamina propria edema, smooth muscle bundles splaying foveolar epithelium, and little to no inflammation. If you have to go to 40× to appreciate the key features of reactive gastritis/gastropathy, it is not reactive gastritis/gastropathy! These features should be apparent at scanning magnification.

Figure 2.21 Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern. This case manifests all the key features of reactive gastritis/gastropathy: surface foveolar mucin cell depletion, a corkscrew-like appearance of the gastric pits, lamina propria edema, smooth muscle bundles extending to toward the surface, and little to no inflammation.

Figure 2.22 Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern. This case is a bit more subtle than the previous cases (Figs. 2.18–2.21) since the gastric foveolar epithelium is not quite as dark or corkscrew-like and lamina propria edema is not seen. Instead, this case features prominent smooth muscle hypertrophy (arrowheads) as it splays and envelopes the involved gastric pits. Gastric foveolar mucin cell depletion and a smattering of chronic inflammation are seen.

Figure 2.23 Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern with occasional congested vessels. This case illustrates that congested vessels are occasionally seen in the reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern (arrowheads). In this case, a quick chart review was helpful to assess for a history of portal hypertension (as would be expected if these congested vessels were a part of portal hypertensive gastropathy) or if a striped watermelon endoscopic appearance was seen (to suggest a diagnosis of gastric antral vascular ectasia). A chart review was noncontributory in this case.

Despite its relatively high prevalence, the terminology surrounding reactive gastritis/gastropathy is a bit contentious. Equivalent terms include “chemical gastritis,” and “chemical gastropathy.” In 1996, a diverse group of gastrointestinal pathology experts convened to discuss key issues related to the classification and grading of gastritis, culminating in the updated Sydney system recommendations.16 Some preferred “chemical” since it more explicitly states the mechanism of injury; some advocated for “gastropathy” instead of “gastritis” since most cases lack clinically significant inflammation to warrant a “gastritis” designation. This nomenclature controversy is trivial and only important in so far as the reader knows that these terms all refer to the same injury pattern.

KEY FEATURES of the Reactive Gastritis/Gastropathy Pattern:

• Reactive gastritis/gastropathy is the most common gastric injury pattern.

• Morphologic features include gastric surface foveolar mucin cell depletion, a corkscrew-like appearance of the gastric pits, lamina propria edema, smooth muscle bundles extending toward the surface, and little to no inflammation.

• Implicated etiologies include bile reflux, medications (NSAIDs, e.g.,), alcohol, portal hypertensive gastropathy, gastric antral vascular ectasia, and autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis.

PITFALLS & PEARLS

Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern can “jump off the slides” and be so eye-catching that it is easy to overlook other important diagnoses. Remember to look at every biopsy for the following sneaky entities, which can be easily obscured by a marked reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern.

CHECKLIST: Select Diagnoses Not To Miss

Erosion (Figs. 2.24 and 2.25)

Erosion (Figs. 2.24 and 2.25)

Ulceration (Fig. 2.26)

Ulceration (Fig. 2.26)

Iron Pill Gastritis (Figs. 2.27 and 2.28)

Iron Pill Gastritis (Figs. 2.27 and 2.28)

Intestinal Metaplasia

Intestinal Metaplasia

Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy (Fig. 2.29)

Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy (Fig. 2.29)

Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia (Fig. 2.30)

Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia (Fig. 2.30)

Dysplasia

Dysplasia

Sneaky Malignant Neoplasms (including Signet Ring and Neuroendocrine Tumors)

Sneaky Malignant Neoplasms (including Signet Ring and Neuroendocrine Tumors)

Autoimmune Metaplastic Atrophic Gastritis

Autoimmune Metaplastic Atrophic Gastritis

Granulomata

Granulomata

Amyloid

Amyloid

Lymphocytic Gastritis Pattern

Lymphocytic Gastritis Pattern

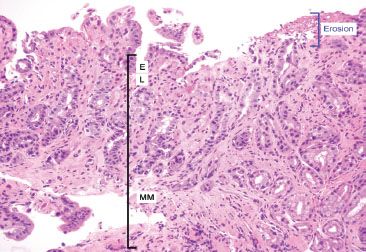

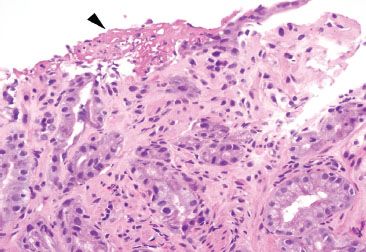

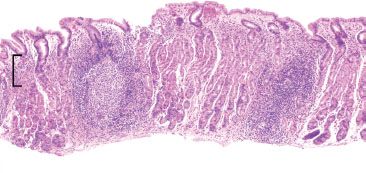

Figure 2.24 Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern and erosion. Erosions (blue bracket) are denudations limited to the mucosa and are often accompanied by fibrino-inflammatory debris. The fibrin deposition is “biologic proof” that true tissue damage has occurred prior to the biopsy, that is this is not a histologic artifact of tissue mishandling. The mucosa consists of the E, epithelium; L, lamina propria; MM, muscularis mucosae.

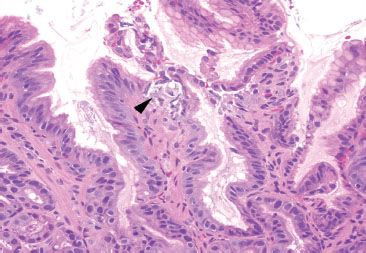

Figure 2.25 Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern with erosion. This example of reactive gastritis/gastropathy features an erosion with focal fibrin deposition (arrowhead).

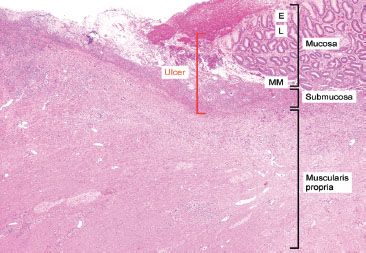

Figure 2.26 Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern and ulceration. In contrast to erosions which are confined to the mucosa, ulcerations extend through and beyond the muscularis mucosae and involve at least the submucosa (red bracket). The mucosa consists of the E, epithelium; L, lamina propria; MM, muscularis mucosae and the submucosa is between the muscularis mucosae and the muscularis propria.

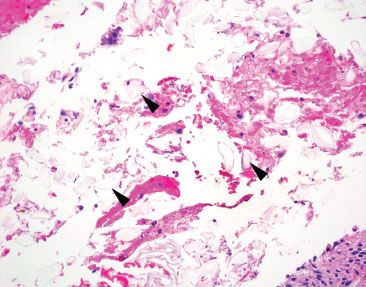

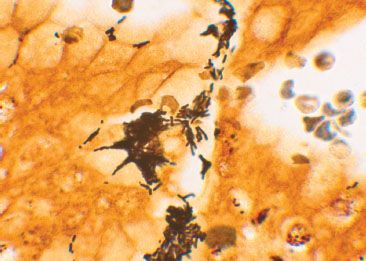

Figure 2.27 Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern, iron deposition. Reactive gastritis/gastropathy is a nonspecific injury pattern, that can be caused by a variety of unrelated entities. Careful scrutiny of the background can occasionally uncover clues to the etiologic injury, such as iron deposition in this case.

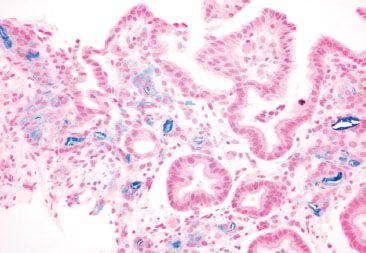

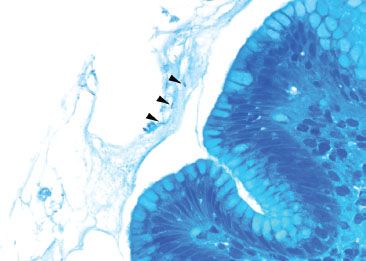

Figure 2.28 Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern, iron deposition (Prussian blue). A Prussian blue iron stain highlights the iron deposition.

Figure 2.29 Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern, portal hypertensive gastropathy. This case shows the usual features of reactive gastritis/gastropathy in addition to a prominence of congested mucosal vessels. A careful chart review uncovered the red flags of cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and endoscopic abnormalities suggestive of portal hypertensive gastropathy. These features support the clinicopathologic diagnosis of portal hypertensive gastropathy.

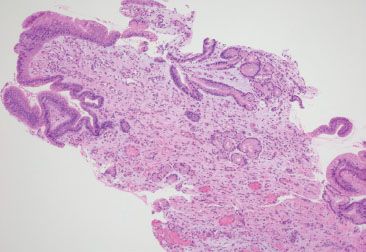

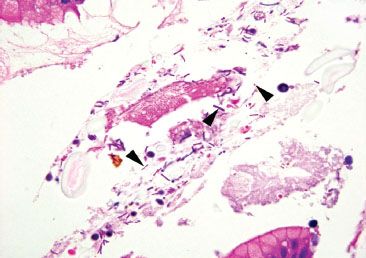

Figure 2.30 Reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern, gastric antral vascular ectasia. Reactive gastritis/gastropathy can be an important clue to the diagnosis of gastric antral vascular ectasia. Other diagnostic features include mucosa thrombi (arrowhead) and an endoscopic image showing a striped-watermelon-like pattern.

FAQ: What is the preferred terminology for cases of reactive gastritis/gastropathy with prominent acute and chronic inflammation (Figs. 2.31 and 2.32)?

Answer: Historically, only minimal chronic inflammation was typical of reactive gastritis/gastropathy; however, an occasional case will feature slightly more acute and chronic inflammation. If the predominant pattern is reactive gastritis/gastropathy, the preferred terminology is “active chronic reactive gastritis/gastropathy.” The alternative wording, “reactive gastritis/gastropathy with acute and chronic inflammation” is often translated by clinicians as “Helicobacter infection.” Certainly, a Helicobacter special stain can be easily performed, although it is almost always negative owing to the microenvironment shifts common to this injury pattern.

Figure 2.31 Active chronic reactive gastritis/gastropathy. In exceptionally striking examples of reactive gastritis/gastropathy, sometimes a prominence of acute and chronic inflammation is seen, as in this case.

Figure 2.32 Active chronic reactive gastritis/gastropathy. The acute inflammation is best appreciated on higher power (arrowheads). The prominent pattern is reactive gastritis/gastropathy with a minimal amount of acute and chronic inflammation.

ACUTE GASTRITIS PATTERN

Figure 2.33 Acute gastritis example. An acute gastritis pattern refers to neutrophils in the gastric epithelium of the stomach (arrows). Acute gastritis pattern is an etiologically nonspecific pattern. This case features a single epithelial cell with nuclear and cytomegaly and smudged chromatin (arrowhead). A confirmatory CMV immunostain was reactive (not shown).

An acute gastritis pattern refers to neutrophils in the epithelium of the stomach (Fig. 2.33). This pattern can be accompanied by erosions, ulcerations, and marked reactive epithelial change. Although this injury pattern is etiologically nonspecific, it is most commonly seen in the setting of medication injury, infections (Helicobacter and CMV), and inflammatory bowel disease. This injury pattern can also be seen with iatrogenic injury (gastrotomy tube, postsurgical setting, chemoradiation), alcohol, and in association with polyps and infiltrating processes such as amyloidosis and neoplasms. This section will discuss the most common etiologies of the acute gastritis pattern and will present practical tips to sort out the individual etiologies.

CHECKLIST: Etiologic Considerations for the Acute Gastritis Pattern

Medications

Medications

Helicobacter

Helicobacter

Cytomegalovirus

Cytomegalovirus

Focally Enhanced Gastritis

Focally Enhanced Gastritis

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

MEDICATIONS

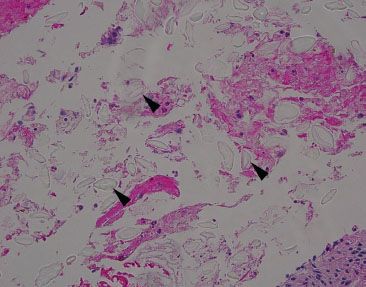

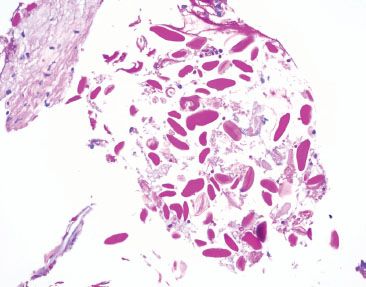

Medication related gastritis is increasingly common as the population ages and our pharmaceutical repertoire expands. The resultant injury pattern is entirely nonspecific and can include a range of pathology, including the reactive gastritis/gastropathy, prominent apoptotic bodies, chronic gastritis with or without acute inflammation, mildly prominent eosinophils, intraepithelial lymphocytosis, granulomata, erosions, ulceration, and vascular degeneration with microthrombi and ischemic damage.23–27 In only a small percentage of cases will the medication be identified. The far more typical scenario is identification of a nonspecific injury pattern, although occasionally refractile or polarizable pill fragments of unclear significance can be seen (Figs. 2.34–2.36). The mechanism of injury may be related to the mechanical damage of the pill as it is “stuck” in the mucosa and causes local physical trauma, or through the resultant downstream chemical effects of the pill itself. Certainly, the most notorious medication culprits include the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) by way of their nonselective inhibition of the cyclooxygenase isoenzymes, resulting in decreased production of mucosal protectant products, such as prostaglandins, mucin, bicarbonate, and dampened microcirculation.28 More recently gastric (and esophageal) mucosal injuries secondary to doxycycline have been described.25–27 Characteristic presentations include severe chest pain shortly after tablet ingestion that is postulated to be related to underlying nerve or vascular ischemia. Endoscopic abnormalities include erosions, ulcerations, friability, and circumferential white “coated”, “hard-to-peel-off” lesions.27 Typical histologic findings include erosions, ulcerations, necrosis, reactive gastritis/gastropathy, and vasculitis with microthrombi. Some advocate referring to these constellation of findings as “toxic-ischemic pattern” (TIP)26 and others advocate the term perivascular “halos” or perivascular zones of edema, reactive myofibroblasts, and lymphoblasts.25 Other medications associated with acute gastritis include potassium chloride in heart failure patients, bisphosphonates in patients with pathologic bone reabsorption, iron, resins, and a variety of chemoradiation therapeutic agents. See also Pigments and Extras subsection, this chapter.

Figure 2.34 Nonspecific pill fragments. Pill fragments not otherwise specified can be easy to miss on H&E because of their transparent appearance (arrowheads).

Figure 2.35 Nonspecific pill fragments. When the substage condenser is flipped, the outline of the pill fragments is often better appreciated (arrowheads) due to increased light refraction. Occasionally, pill fragments are refractile.

Figure 2.36 Nonspecific pill fragments (PAS). Often, these pill fragments are bright pink on PAS staining, which sometimes raises concern for swallowed parasitic ova; however, parasitic ova are exceptionally uncommon, if not reportable. Moreover, parasitic ova are expected to be more uniform is size and shape, associated with a tissue reaction, and seen in the clinical setting of pertinent clinical symptoms.

CHECKLIST: Select Medications Commonly Associated with the Acute Gastritis Pattern:

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Doxycycline

Doxycycline

Potassium Chloride

Potassium Chloride

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates

Iron

Iron

Resins

Resins

Various Chemoradiation Therapeutic Agents

Various Chemoradiation Therapeutic Agents

HELICOBACTER PYLORI

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative helical or curved bacillus known to colonize more than half of the human population,29 and is found in up to 20% of gastric biopsies in North America.30 Fecal–oral contamination is the major mode of transmission, although the organisms have also been cultivated from vomitus and saliva.29,31–34 Dyspepsia is the most common presenting symptom and endoscopic abnormalities can include gastric and or peptic ulcerations. Recognition of the organism is important for symptom resolution and to prevent infection related neoplasia, such as gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, glandular dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma.35–37 In addition, Helicobacter pylori infections have been associated with iron deficiency anemia, idiopathic thrombocytic purpura, and have an inverse relationship with asthma, allergy, atopic disease, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.32

In classic examples of Helicobacter pylori gastritis, the diagnosis can almost be made at scanning magnification owing to its characteristic histologic findings: a superficial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation that often appears band-like and snug beneath the surface foveolar epithelium, brisk acute inflammation, and prominent lymphoid aggregates (Figs. 2.37–2.39). Occasionally, a lymphocytic gastritis pattern can also be seen (Figs. 2.40–2.42).38,39 See Lymphocytic Gastritis Pattern in this chapter. The Helicobacter pylori organisms can be easily spotted on H&E without the use of ancillary stains.30 Efficient “bug hunts” target mucin-rich foci near the surface, particularly those that are acutely inflamed (Figs. 2.43–2.45). Characteristically, the organisms appear as curved rods (Figs. 2.46 and 2.47). Occasionally, normal oral and gastrointestinal flora can raise concerns for Helicobacter. Important points of distinction from oral and gastrointestinal flora include the following:

Figure 2.37 Acute gastritis pattern, Helicobacter pylori. This prototypic example of Helicobacter pylori gastritis shows prominent lymphoid aggregates with a germinal center and a superficial lymphoplasmacytosis that appears band-like and snug beneath the surface foveolar epithelium (bracket). These characteristic features are highly suggestive of Helicobacter gastritis at scanning magnification. Helicobacter pylori was identified on higher-power (not shown).

Figure 2.38 Acute gastritis pattern, Helicobacter pylori. This example shows features highly suggestive of Helicobacter gastritis at scanning magnification: prominent lymphoid aggregates and a band-like superficial lymphoplasmacytosis (bracket) are seen.

Figure 2.39 Acute gastritis pattern, Helicobacter pylori. On high power, a superficial lymphoplasmacytosis is seen along with scattered pockets of acutely inflamed pits (arrowheads). This histologic appearance is highly suggestive of Helicobacter, requiring a thorough “bug hunt” for the organism. Helicobacter pylori were identified on higher-power (not shown).

Figure 2.40 Lymphocytic gastritis pattern, Helicobacter pylori. A lymphocytic gastritis pattern can be an important red flag to the diagnosis of Helicobacter gastritis, as seen in this case. This case also features the usual characteristics of Helicobacter, namely a band-like superficial lymphoplasmacytosis and scattered pockets of acute inflammation (arrowheads). Intestinal metaplasia is seen at the far right (arrow).

Figure 2.41 Lymphocytic gastritis pattern, Helicobacter pylori. On higher power, the intraepithelial lymphocytosis is easily appreciated. Also seen are the superficial lymphoplasmacytosis and pockets of acute inflammation (arrowheads) characteristic of Helicobacter. Helicobacter pylori was identified on higher-power (not shown).

Figure 2.42 Lymphocytic gastritis pattern, Helicobacter pylori. This case originated from a patient with Celiac disease. A Helicobacter immunostain was negative.

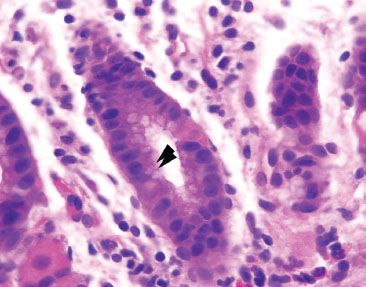

1. Location: Helicobacter pylori prefer close association with the surface epithelium, unlike the normal oral and gastrointestinal flora, which are found farther from the surface epithelium and often admixed with luminal debris (Fig. 2.44 vs. Fig. 2.48). It is worthwhile to note that occasionally the Helicobacter organisms can be found in gastric pits and glands, a finding not typical of oral and gastrointestinal flora (Figs. 2.49 and 2.50).40

Figure 2.43 Acute gastritis pattern, Helicobacter pylori. Unfortunately, most of the time the diagnosis of Helicobacter requires usage of the dreaded 40× objective. Thankfully, only one organism is needed for the diagnosis, and efficient “bug hunts” can speed the diagnostic process by targeting acutely inflamed tissue fragments, particularly those cases that feature superficial, mucin-rich foci, as seen here (arrowheads). Characteristically, the bacilli are helical, slightly curved, or cinched in the midpoint.

Figure 2.44 Acute gastritis pattern, Helicobacter pylori. Note the close association of the Helicobacter pylori organisms to the foveolar epithelium (arrowheads) and their position within the gastric pit (arrow); these are important points of distinction from the normal gastrointestinal tract and oral flora to be discussed below.

Figure 2.45 Acute gastritis pattern, Helicobacter pylori (arrowheads).

Figure 2.46 Acute gastritis pattern, Helicobacter pylori (Warthin-Starry). The organisms appear a bit plumper on a Warthin-Starry since this process coats the organism with the silver compound.

Figure 2.47 Acute gastritis pattern, Helicobacter pylori (Diff–Quik). A Diff–Quik special stain can highlight the organisms (arrowheads).

Figure 2.48 Gastrointestinal tract and oral bacteria. Unlike H. pylori, the gastrointestinal tract and oral bacteria are not found in intimate association with the surface epithelium, and, instead, are more commonly found amidst luminal debris and mixed bacterial flora with rods and cocci, as seen here (arrowheads). Compare with Figure 2.44.

Figure 2.49 Acute gastritis pattern, Helicobacter pylori. Unlike the gastrointestinal tract and oral bacteria, Helicobacter pylori can be found within the gastric pits (arrowheads).

Figure 2.50 Acute gastritis pattern, Helicobacter pylori (Diff–Quik).

2. Associated bacteria: Helicobacter pylori clusters have nearly identical similarly shaped organisms, whereas the normal oral and gastrointestinal flora are found as mixed flora composed of a mixed population of rods and cocci (Figs. 2.43–2.45 vs. Fig. 2.48).

3. Background: Lastly, Helicobacter pylori is almost always found suspended within a background of active chronic inflammation, as outlined earlier. In contrast, the normal oral and gastrointestinal flora show no consistent relationship with mucosal injury since they are swallowed, endogenous flora. In challenging cases, the Helicobacter pylori immunostain can be helpful.

In general, Helicobacter organisms and their related pathology are most easily seen in the antrum; however, in cases of intestinal metaplasia or marked reactive gastritis/gastropathy involving the antrum, the resultant microenvironment changes are thought to cause the organisms to shift to the oxyntic mucosa or even cardia, underscoring the importance of looking at every stomach biopsy carefully for Helicobacter. Unfortunately, sometimes the Helicobacter organisms can be difficult to find, especially in treated cases that usually show small, rounded, and rare organisms (Figs. 2.51 and 2.52). In such cases, the Helicobacter immunostain is recommended.30

Figure 2.51 Acute gastritis pattern, partially treated Helicobacter pylori (Helicobacter pylori immunostain). In partially treated cases, the organisms can be exceedingly difficult to find because of their altered morphology. In this case, the organisms appear small and rounded, requiring the aid of the Helicobacter pylori immunohistochemical stain for confirmation.

Figure 2.52 Acute gastritis pattern, partially treated Helicobacter pylori (Helicobacter pylori immunostain). Note the coccoid morphology, which results from partial treatment effect. These organisms are usually rare and almost impossible to detect on H&E alone.

PEARLS & PITFALLS

Highlights from the 2013 Rodger C. Haggitt Gastrointestinal Pathology Society Recommendations for the Appropriate Use of Special Stains for Helicobacter Detection:30

• The Helicobacter immunostain is the recommended stain of choice based on its superior sensitivity in comparison to histologic stains, and its enhanced ability to detect Helicobacter with treatment effect (coccoid forms) and rare organisms present deep in the glands or intracellular locations

• Indications for the Helicobacter immunostain include the following, assuming no Helicobacter organisms are seen on H&E:

• Inflamed gastric biopsies, including cardiac mucosa and cases of reactive gastritis/gastropathy, although the yield is low (less than 10%) in the absence of moderate-marked acute and chronic inflammation

• Lymphocytic gastritis pattern

• Chronic inactive gastritis with concomitant positive Helicobacter serologies, gastroduodenal ulcers, gastric MALT-type lymphoma or adenocarcinoma, duodenal lymphocytosis, prior Helicobacter infection, and or high-risk demographics

• Inflamed or ulcerated duodenal biopsies with gastric foveolar metaplasia

• Contraindications to Helicobacter immunostains include the following:

• Cases with Helicobacter organisms present on H&E

• Background normal mucosa

• Reactive gastritis/gastropathy lacking inflammation

• Uninflamed gastric polyps

• A clinical request to “rule-out” Helicobacter; thorough histologic examination of the H&E slide is up to 95% sensitive for Helicobacter detection, particularly if greater than five high-power fields (HPFs) are examined

• The society argues against “up-front” Helicobacter immunostains on all esophageal, gastric, and small bowel biopsies, citing insufficient evidence for reduced turnaround time

• No current recommendations were provided for granulomatous gastritis and eosinophilic gastritis

PEARLS & PITFALLS

A lymphocytic gastritis pattern refers to an intraepithelial lymphocytosis that is most easily seen in the superficial foveolar epithelium (Figs. 2.40–2.42). Helicobacter infections and celiac disease are the most common association with this injury pattern.38,39 If Helicobacter is not identified on H&E, a Helicobacter immunostain is recommended.30 Biopsy material negative for Helicobacter should be accompanied by recommendations to exclude Helicobacter with pertinent clinical studies, such as serology, urease breath test, or stool antigen studies. Similarly, celiac disease should be considered when examining any tandem small bowel specimens. If a small bowel specimen is not provided, it is worthwhile to recommend exclusion of celiac disease with pertinent clinical serologies. See also Lymphocytic Gastritis Pattern in this chapter.

PEARLS & PITFALLS

One of the most challenging aspects of pathology is recognizing that a single biopsy can have more than one important diagnosis; for example, Helicobacter gastritis can have such striking histologic findings that other key diagnoses can be easily overlooked. Routine consideration of these select diagnoses will avoid such missteps.

CHECKLIST: Select Diagnoses Not To Miss on Busy Helicobacter Gastritis Cases:

Granulomata

Granulomata

Amyloid

Amyloid

Lymphocytic Gastritis Pattern

Lymphocytic Gastritis Pattern

Intestinal Metaplasia

Intestinal Metaplasia

Glandular Dysplasia

Glandular Dysplasia

Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma

Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma

Infiltrating Adenocarcinoma and Sneaky Signet-Ring Cells

Infiltrating Adenocarcinoma and Sneaky Signet-Ring Cells

FAQ: What is the best way to approach cases with morphologic features strongly suggestive of Helicobacter infection but in which no organisms are found?

Answer: In challenging cases, a recommendation to clinically exclude Helicobacter with pertinent clinical studies may be prudent (serology, urease breath test, or stool antigen studies). Helicobacter cases can be among the most satisfying because they provide an etiology for the histologic findings and clinical symptoms, and effective treatment can result in symptomatic relief and decreased incidence of gastric MALT lymphoma, glandular dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma. What could be better?! On the other hand, cases with morphology provocative for Helicobacter and no obvious organisms are among the most frustrating because an unrecognized infection can lead to persistent symptoms and increased risk for gastric MALT lymphoma, glandular dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma. What could be worse?! These cases are unavoidably time-consuming and require diligent inspection of multiple HPFs as well as usage of the Helicobacter pylori immunostain. When the classic features of Helicobacter are seen but the organisms are not apparent with the Helicobacter immunostain, a standard note to encourage additional clinical studies is of use. Note, this approach should not be applied to every “juicy” case of chronic gastritis, else it would be overused and its value would be lost. This note is recommended for cases with a minimum of brisk acute and chronic gastritis and superficial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, with or without prominent lymphoid aggregates and lymphocytic gastritis pattern.

Sample Note: Active Chronic Gastritis Suspicious for Helicobacter

Stomach, Biopsy:

• Antral mucosa with marked active chronic gastritis and superficial lymphoplasmacytosis.

Note: The biopsy shows marked active chronic gastritis with superficial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation. These features are very suspicious for a Helicobacter infection. Although no organisms were identified on the Helicobacter immunostain, clinical exclusion of a Helicobacter infection is recommended with pertinent clinical studies (serology, urease breath test, or stool antigen studies).

HELICOBACTER HEILMANNII

Not every Helicobacter gastritis case is caused by Helicobacter pylori. To date, phylogenetic studies have identified more than 50 species within the Helicobacter genus. The most familiar of these is Helicobacter heilmannii which itself refers to at least five different species, leading some experts to advocate for the more precise nomenclature of “Helicobacter heilmannii-like organisms”. Unfortunately, much less is known about Helicobacter heilmannii-like infections owing to their rarity. The available literature has shown important similarities with Helicobacter pylori, including shared symptomatology (abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting), antral predominant active chronic inflammation with prominent lymphoid aggregates (Figs. 2.53–2.56), gastric and duodenal ulcerations, and suggest an increased risk for gastric MALT lymphoma and adenocarcinoma, underscoring their biologic importance.41–44 Limited anecdotal evidence has shown Helicobacter heilmannii–like infections respond to the same treatment regime as Helicobacter pylori infections. Important points of distinction of Helicobacter heilmannii–like infections from Helicobacter pylori include the following:

Figure 2.53 Acute gastritis pattern, Helicobacter heilmannii. At low power, Helicobacter heilmannii and Helicobacter pylori gastritis look similar with antral predominant active chronic inflammation and prominent lymphoid aggregates. Helicobacter heilmannii was identified on higher power (not shown). Compare with Figure 2.37.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree