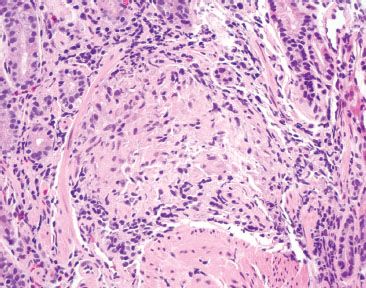

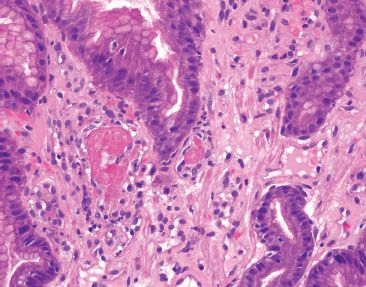

e-Figure 2.1

Which of the following is the best diagnosis for this stomach biopsy submitted as “rule-out carcinoma?”

A. Schistosomiasis

B. 90Yttrium-labeled microspheres

C. Somatostatinoma with psammoma bodies

D. Dystrophic calcifications

Answer: 90Yttrium-labeled microspheres (B).

90Yttrium-labeled microspheres are used in the selective treatment of unresectable primary and metastatic hepatic malignancies. They can cause unintended mucosal injury to nontargeted organs, such as 90Yttrium-labeled microsphere related esophagitis, gastritis, duodenititis, pancreatitis, and cholecystitis (1–4). In ideal specimens, the characteristic microspheres are adjacent to a radiation gastritis pattern of injury with lamina propria hyalinization, atypical stromal, endothelial, and epithelial cells, and prominence of ectatic, damaged vessels. Unfortunately, as in this case, some cases feature such prominent ulceration and or acute and chronic inflammation that the background radiation injury pattern is obscured. Since CMV viral cytopathic effect can also be obscured by this injury pattern, it is always a good idea to perform a CMV IHC (which was negative in this case). See also 90Yttrium-labeled microspheres, Stomach Chapter.

Anecdotally, 90Yttrium-labeled microspheres can raise concerns for Schistosomiasis (A), somatostatinoma with psammoma bodies (C), and dystrophic calcifications (D). Schistosomiasis would be neither solid in structure nor uniform in size, and would be associated with eosinophilic rich inflammation (A). Psammoma bodies are often seen in somatostatinomas, but there is no neuroendocrine neoplasm to suggest this diagnosis. In addition, psammoma bodies have a laminated appearance, or inner mineralized material arranged in concentric rings (C). Dystrophic calcifications appear more irregular and haphazard than these uniform and perfectly spherical structures (D). A von Kossa stain can be helpful in challenging cases (90yttrium-labeled microspheres are nonreactive and calcifications are positive).

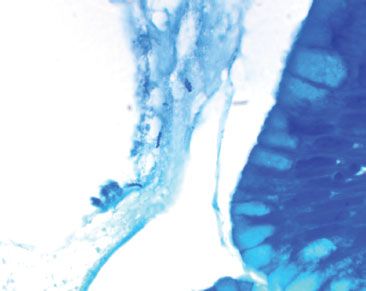

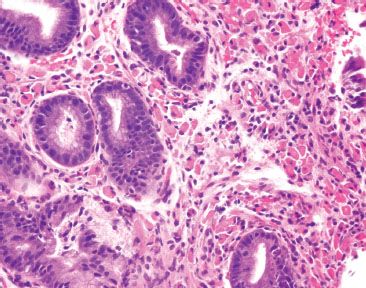

E-QUIZ QUESTION 2 (e-FIG. 2.2)

e-Figure 2.2

Which of the following is the best diagnosis for this antral biopsy originating from a 16-year-old boy with bloody diarrhea?

A. Sarcoidosis

B. Upper-tract Crohn disease

C. Granular cell tumor

D. Antral mucosa with lamina propria granuloma, see note.

Answer: Antral mucosa with lamina propria granuloma, see note (D).

This case features a single lamina propria granuloma in a background of acute and chronic gastritis. Recall, granulomata are collections of epithelioid histiocytes surrounded by a cuff of lymphocytes and plasma cells. This finding can be seen in a variety of settings, including infection (Helicobacter, mycobacterial, fungal), medication, foreign body reaction, sarcoidosis, upper-tract Crohn disease, vasculitis, common variable immunodeficiency, and near a neoplasm, among others. Therefore, the diagnosis cannot be too dogmatic unless the clinical history is very straightforward. In general, such cases are best signed out descriptively (D), and follow with a note that places the findings in the most likely clinicopathologic context. For example, this finding represents upper tract Crohn disease if the patient had a well-established history of Crohn disease and medication injury and self-limited infections had been excluded) (B). Similarly, identical findings can be seen with sarcoidosis if the patient had an established history of sarcoidosis, although the background acute and chronic inflammation is not typical of sarcoidal granulomatous gastritis (A). Ill-formed granulomata can raise concerns for a granular cell tumor at low-power because of the abundant pink cytoplasm, but at high-power the requisite granular cytoplasm characteristic of granular cell tumor is not seen (C). In challenging cases, an S100 protein stain can be helpful (granular cell tumors show strong S100 protein nuclear and cytoplasmic reactivity and granulomata are S100 protein nonreactive). Of note, a Helicobacter immunostain was negative, as were special stains for fungal elements (PAS) and mycobacterium (AFB). See also Granulomatous Gastritis, Stomach Chapter.

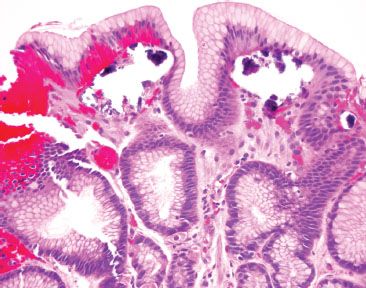

E-QUIZ QUESTION 3 (e-FIG. 2.3)

e-Figure 2.3

Which of the following is the best diagnosis for this structure (Diff–Quik, 100×)?

A. Helicobacter heilmannii

B. Helicobacter pylori

C. Food debris

D. Candida

Answer: Helicobacter heilmannii (A).

The indicated area shows Helicobacter heilmannii as evidenced by the elongated, spiraled, slender forms that are not adherent to the foveolar epithelium (A). In contrast, Helicobacter pylori organisms are shorter, chubbier, with a slightly narrowed midpoint (B). In addition, Helicobacter pylori organisms are typically more numerous, adherent to the foveolar epithelium, and seen in a more prominent background of acute and chronic inflammation (not shown). These structures are too small and regular to be food debris (C). Also, food debris would not be highlighted by this bacterial special stains. See also Helicobacter gastritis, Stomach Chapter.

On morphologic grounds alone we can exclude Candida because the indicated structure lacks the characteristic large pseudophae forms of Candida, which should be readily appreciated on 40× (the depicted image is under oil immersion, 100×) (D). See also Candida Esophagitis, Esophagus Chapter.

E-QUIZ QUESTION 4 (e-FIG. 2.4)

e-Figure 2.4

Which of the following is the best diagnosis for this stomach biopsy?

A. Unremarkable gastric mucosa

B. Iron pill gastritis

C. Kayexalate

D. Mucosal calcinosis

Answer: Mucosal calcinosis (D).

This image features mucosal calcinosis (D). These firm calcifications are roughly the consistency of bone and, consequently, are difficult to cut, resulting in “tissue holes” as the calcifications are lost during processing. These “tissue holes” can be important red flags to the diagnosis, though, and should be examined carefully. Calcinosis can be highlighted by the von Kossa special stain (calcium is black). The superficial calcifications eliminate choice A (unremarkable gastric mucosa). Iron pill gastritis is a terrific mimic and, indeed, a few of these cases turn out to be a conglomerate of calcium and iron, making routine ordering of both the von Kossa and Prussian blue special stains worthwhile (calcium is black with von Kossa and iron is blue with Prussian blue). Iron pill gastritis, Kayexalate-associated injury, and mucosal calcinosis are all common in renal failure patients. Although calcium and Kayexalate both appear purple, Kayexalate crystals are characterized by a “fish-scale” or “mosaic” appearance and commonly seen in a background of ulceration and ischemic injury due to the osmotic effects of the diluent sorbitol solution (C). See also Resins, Acute Esophagitis, Esophagus Chapter. Mucosal calcinosis is most often seen in the setting of renal failure, but can also be seen with parathyroid disorders, tumor lysis syndrome, atrophic gastritis, hypervitaminosis A, organ transplantation, gastric neoplasia, uremia with eucalcemia/euphosphatemia, and with the use of aluminum-containing antacids, citrate-containing blood products, isotretinoin, and sucralfate (5, 6). If there is no clear cause to the finding of mucosal calcinosis, it is worthwhile to contact the clinician and suggest a careful clinical workup to search for causes of calcium dysregulation and potential cardiac involvement, which can be fatal. See also Calcinosis, Stomach Chapter.

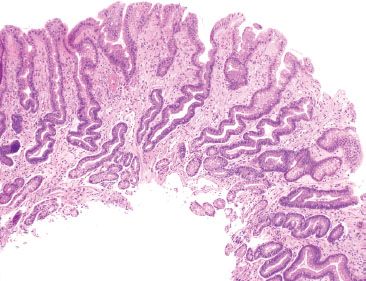

E-QUIZ QUESTION 5 (e-FIGS. 2.5 and 2.6)

e-Figure 2.5

e-Figure 2.6

Which of the following is the best diagnosis for this gastric biopsy in a patient with a history of mixed connective tissue disease and whose upper endoscopy featured a striped appearance to the gastric mucosa?

A. Reactive gastritis/gastropathy

B. Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy (PHG)

C. Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia (GAVE)

D. Amyloidosis

Answer: Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia (GAVE) (C).

At low power, the image depicts a prominent reactive gastritis/gastropathy pattern with foveolar mucin cell depletion, a corkscrew-like appearance of the foveolar epithelium, lamina propria edema, smooth muscle bundles splaying foveolar epithelium, and minimal inflammation (A) (e-FIG. 2.5). Nevertheless, reactive gastritis/gastropathy is not a good enough diagnosis because there is more to the story. Recall, the history of a striped watermelon-like appearance on endoscopic evaluation, suggestive of GAVE (C). Moreover, mucosal thrombi are identified on higher power (e-FIG. 2.6). Together, these clinicopathologic features support a diagnosis of GAVE. As in this case, GAVE is often seen in the setting of mixed connective tissue diseases or other autoimmune diseases. Choice B is incorrect because mucosal thrombi are not characteristic of portal hypertensive gastropathy and a history of portal hypertension was not provided. Choice D is incorrect because amyloid deposits were not seen (the high-power image features fibrin thrombi, which are hyperpink and confined to the luminal space, as opposed to amyloid, which appears faintly pink and diffusely infiltrates the lamina propria and vascular walls). See also GAVE, Stomach Chapter.

E-QUIZ QUESTION 6 (e-FIG. 2.7)

e-Figure 2.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree