CHAPTER 3

Stomach

INTRODUCTION

The stomach functions to store food and begin the process of digestion. It can be divided physiologically, anatomically, and endoscopically. Upon entering the stomach, one looks directly toward the greater curvature and encounters the gastric rugae. On close inspection, the mucosa has a subtle mosaic pattern, representing the areae gastricae. Any process causing mucosal edema will accentuate this pattern. Gastric folds should flatten with full insufflation. The incisura angularis (gastric notch), located on the distal lesser curvature, is an important landmark that helps to differentiate the gastric body from the antrum and is a common location for benign gastric ulceration. Not unexpectedly, given the histologic differences, the antral mucosa appears endoscopically different from the gastric body.

Inflammatory disorders are the most common gastric disorders encountered by endoscopists. As with any endoscopic abnormality, gastric ulcers should be thoroughly characterized, noting location, size, and appearance, because these characteristics yield important information about the likelihood of neoplasm. Similarly, improved resolution with newer endoscope systems has increased the sensitivity for the endoscopic detection of histologic gastritis. Helicobacter pylori gastritis may be suspected at the time of endoscopy, although definitive diagnosis requires confirmation, given that “endoscopic abnormalities” may represent normal findings, and conversely, a normal endoscopic appearance may not represent normal histology.

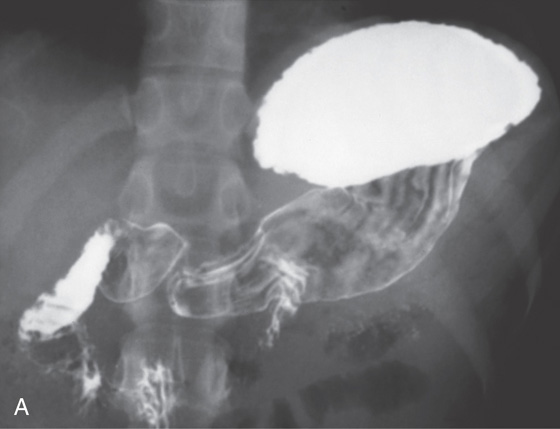

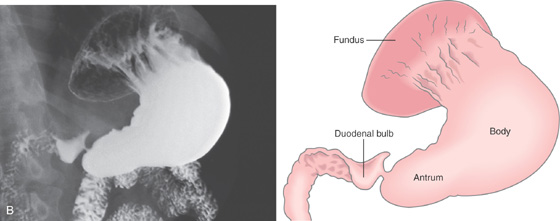

A, The gastric fundus is well filled with barium, providing an air contrast view of the body, antrum, and duodenal bulb. Normal-appearing gastric rugae are seen in the proximal body. The antral and duodenal mucosae are smooth. Barium is entering the second portion of the duodenum.

B, Barium is filling the gastric body and antrum, showing normal contour. An air contrast view of the gastric fundus is shown. The distal duodenum and proximal jejunum are inferior to the gastric body.

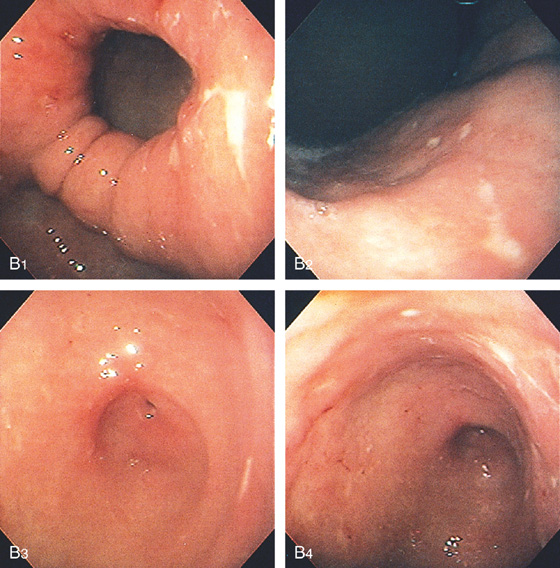

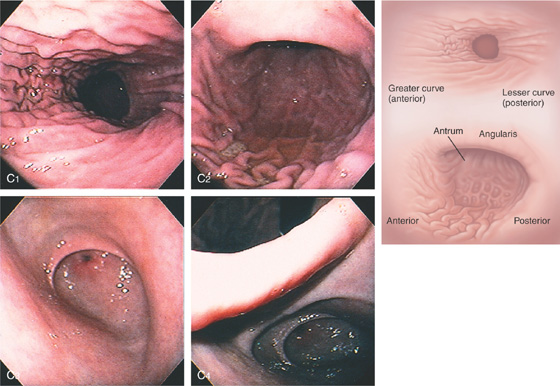

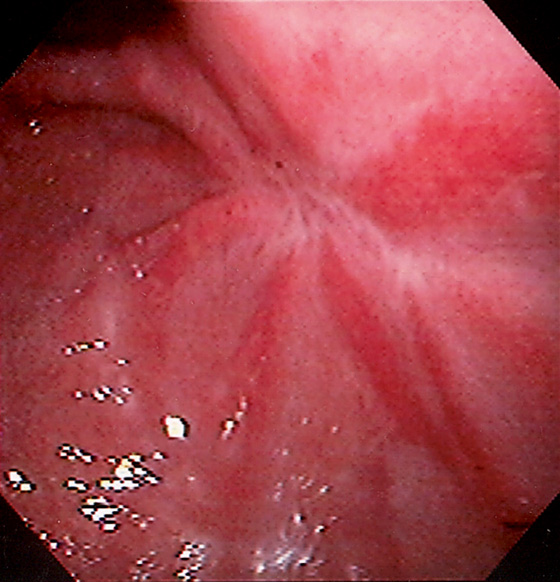

C, As the endoscopic tube enters the stomach, the greater curvature is on the left and the lesser curvature on the right, with the angularis (i.e., incisura angularis) in the distance. Gastric rugae are more prominent on the greater than the lesser curvature (C1). Normal-appearing rugae are seen in the distal body, extending to the level of the angularis (C2). The antral mucosa is smooth, and the pylorus is in the distance (C3). The endoscope tip is elevated, and the scope is rotated slightly to the left, identifying the pylorus and angularis, with the endoscope seen above (C4).

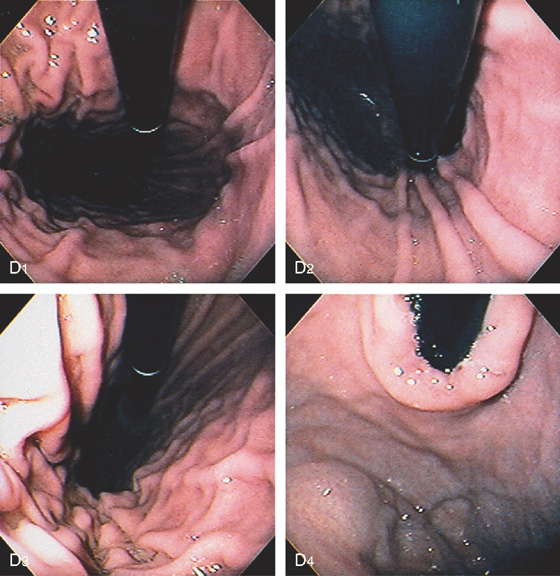

Figure 3.1 NORMAL ANATOMY

D, The endoscope is withdrawn to the level of the angularis. The lesser curvature forms the right wall and the greater curvature the left wall. The gastric rugae are more prominent on the left wall (D1). With further withdrawal of the endoscope, small rugae are seen on the lesser curvature (D2). More prominent rugae are on the opposite wall (greater curvature) with the endoscope rotated to the left (D3). With still further withdrawal of the endoscope, the gastric fundus and cardia are shown. The fundus has no rugae, and blood vessels are present. A small rim of gastric mucosa (gastric cardia) can be seen encircling the endoscope (D4).

Figure 3.2 ANTERIOR–POSTERIOR RELATIONSHIP

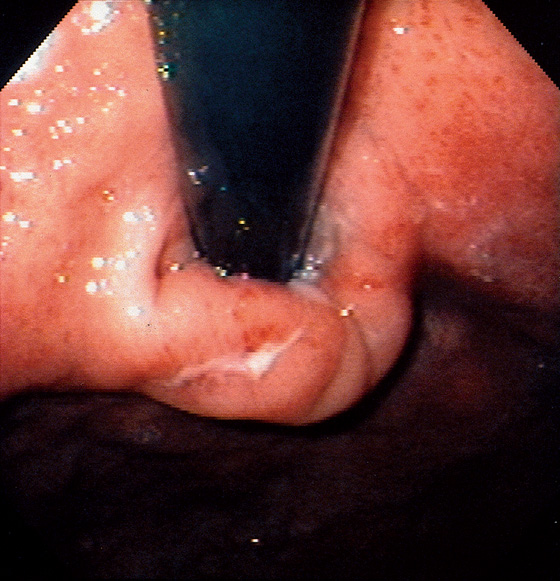

With the patient supine, indentation of the anterior wall documents the anterior–posterior relationship of the angularis.

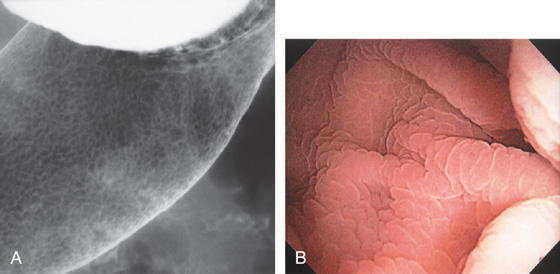

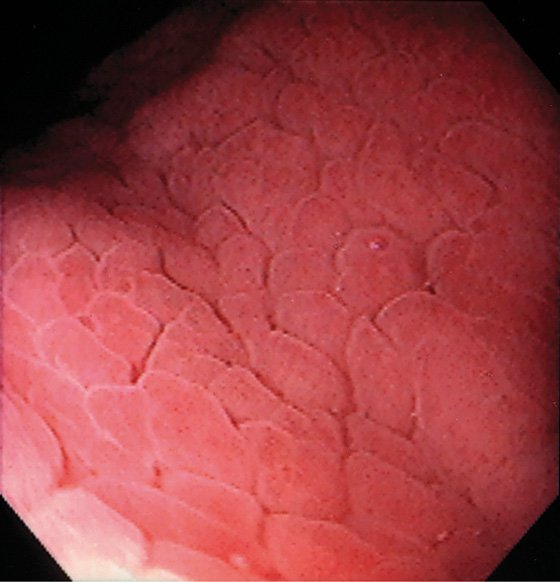

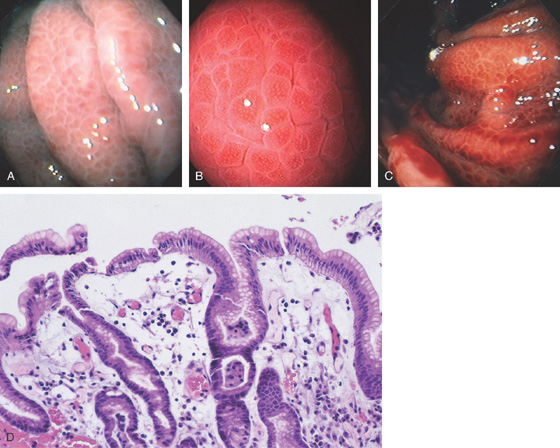

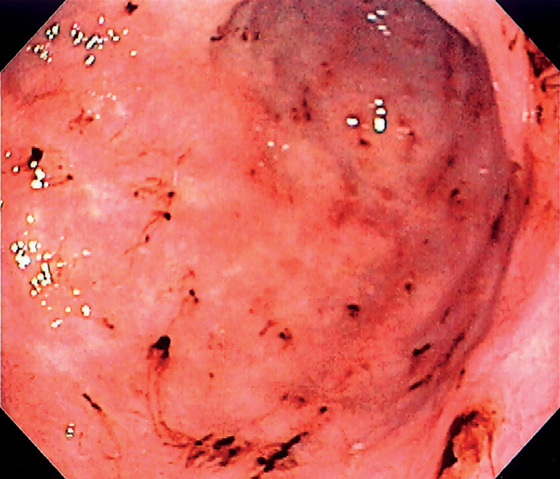

Figure 3.3 AREAE GASTRICAE

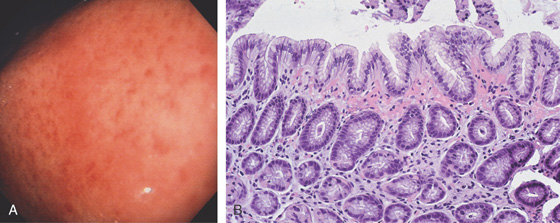

A, This pattern may be seen in healthy individuals or can be associated with gastritis. Endoscopically, the pattern may not be as well appreciated as with a barium study. B, The normal areae gastricae as seen underwater. Clarity is enhanced when structures are viewed underwater.

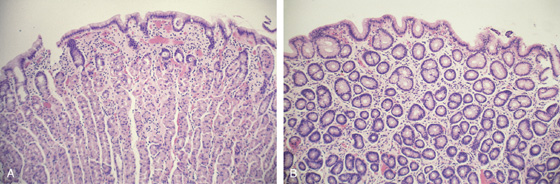

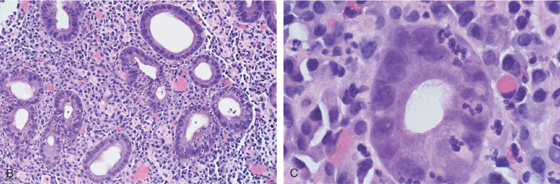

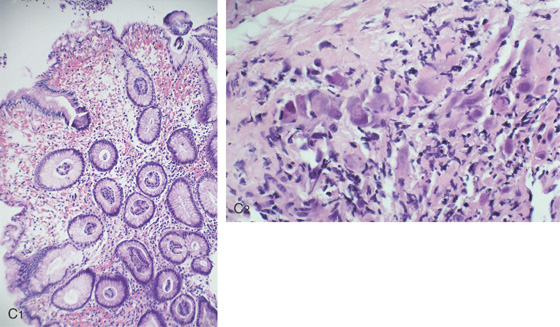

Figure 3.4 GASTRIC HISTOLOGY

A, The normal histology of the gastric body is demonstrated. The foveolar surface epithelium is shown. The deeper structures represent the fundic glands. The vertical orientation of the glands is evident. B, The normal antral mucosa is composed of deep pits lined by foveolar epithelium. Mucin-producing glands are present.

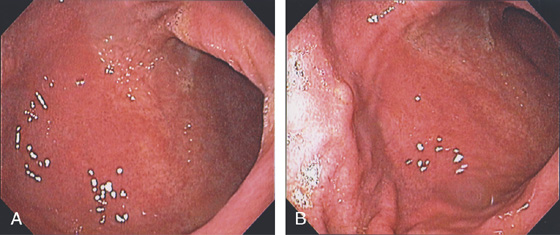

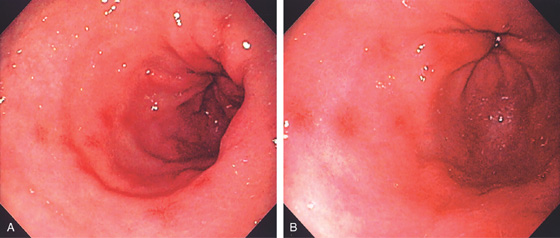

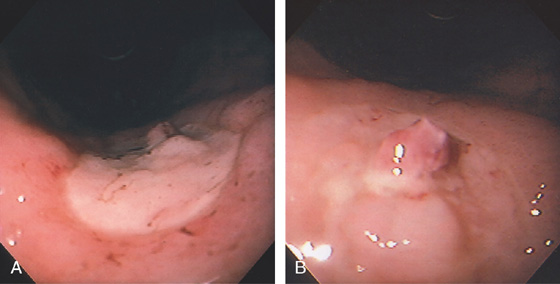

Figure 3.5 GASTRIC BODY–ANTRUM DEMARCATION

A, B, The gastric mucosa often changes in appearance near the angularis, in association with the histopathologic change. This change may be more striking in patients with associated gastritis.

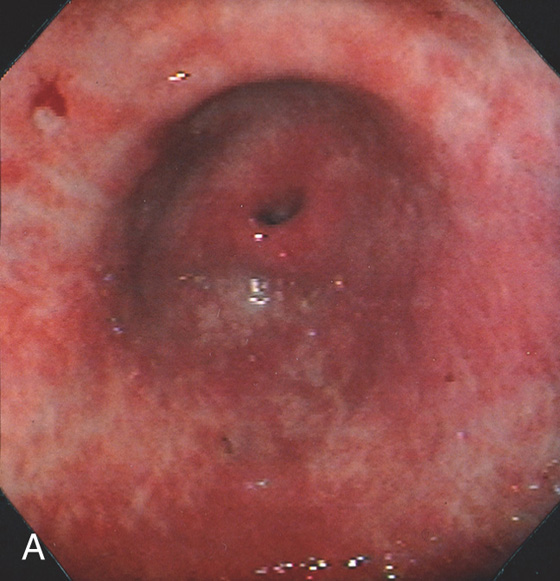

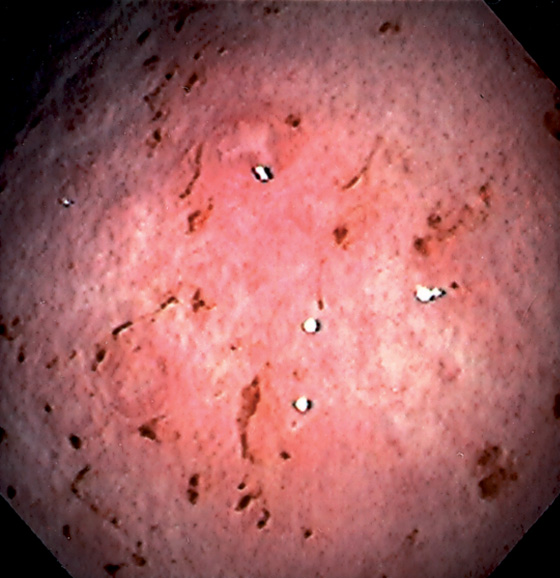

Figure 3.6 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

Mild superficial gastritis results in erythema and prominence of the areae gastricae (as seen underwater).

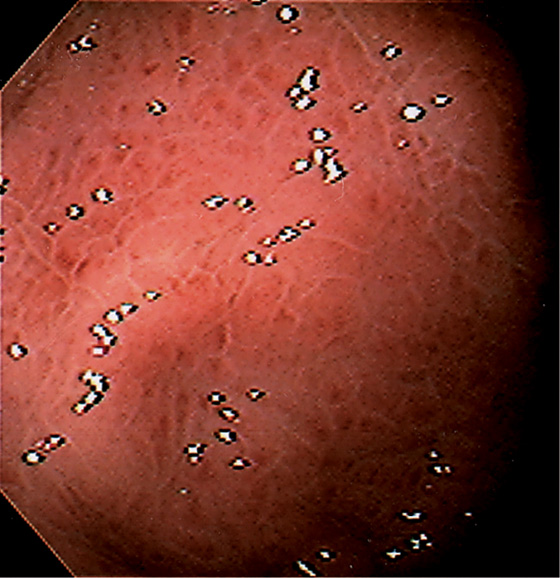

Figure 3.7 FOCAL HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

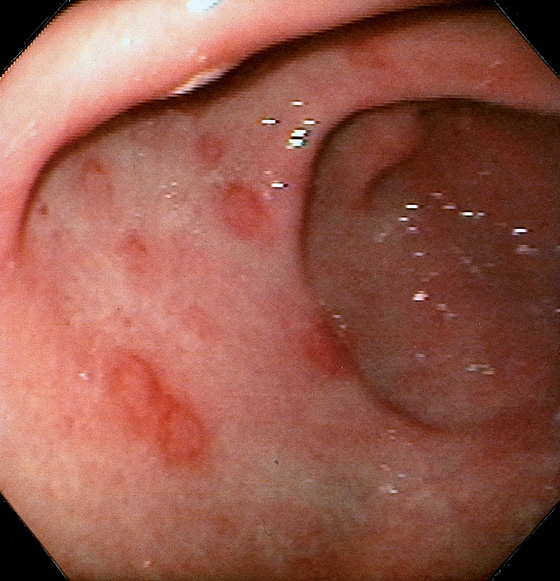

Patchy areas of inflammation in the proximal gastric body are well demarcated by the surrounding atrophic mucosa.

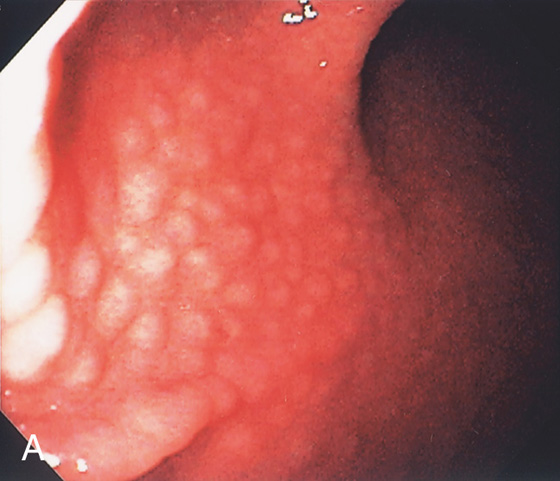

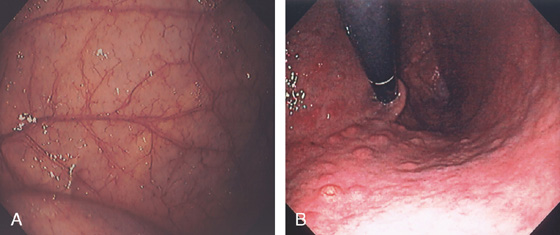

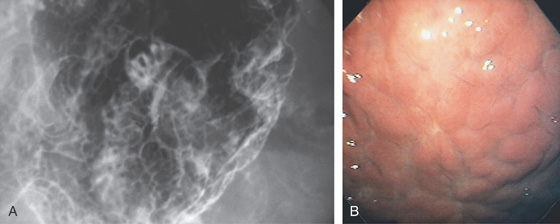

Figure 3.8 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

A, Multiple nodular filling defects and prominence of the areae gastricae in the gastric body. This pattern may represent inflammation or an infiltrating neoplasm. B, Diffuse nodularity, with overlying normal mucosa.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Helicobacter pylori Gastritis (Figure 3.8)

Lymphocytic gastritis

Sarcoidosis

Lymphoma

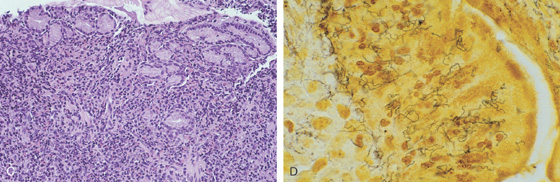

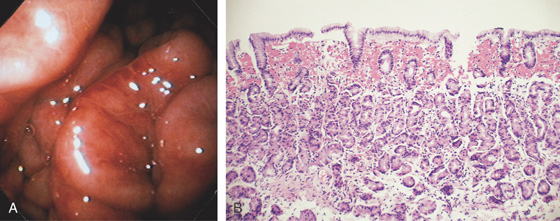

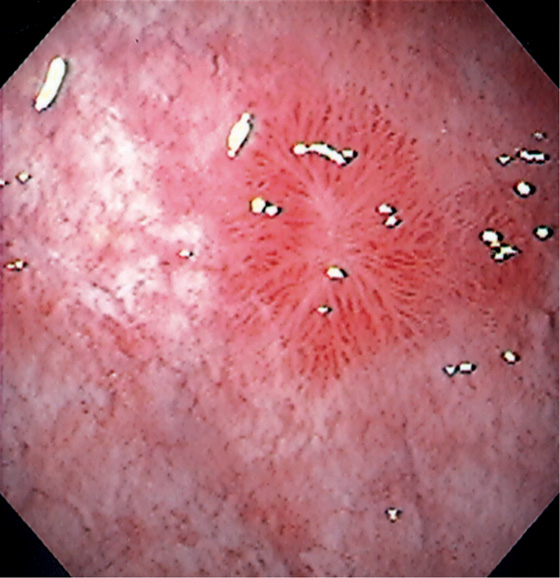

Figure 3.9 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

A, There is marked nodularity of the anterior wall of the gastric body when viewed from this angle. This has been termed a “chicken skin” appearance.

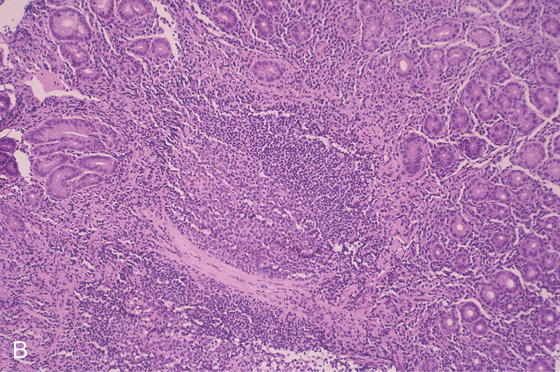

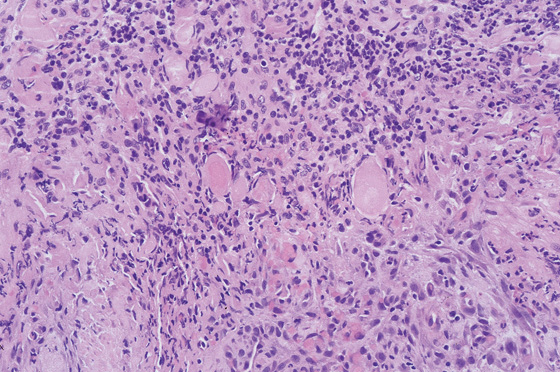

B, Follicular lymphoid hyperplasia associated with prominent chronic gastritis. An enlarged lymphoid follicle with germinal center is present.

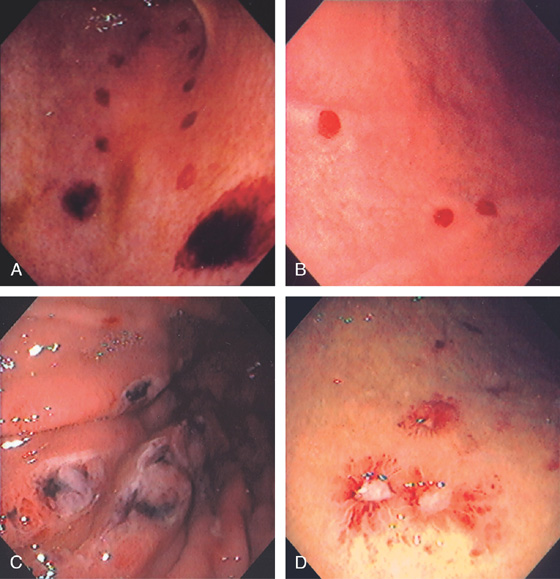

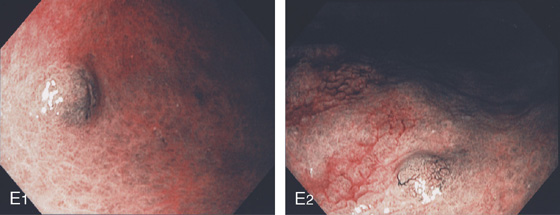

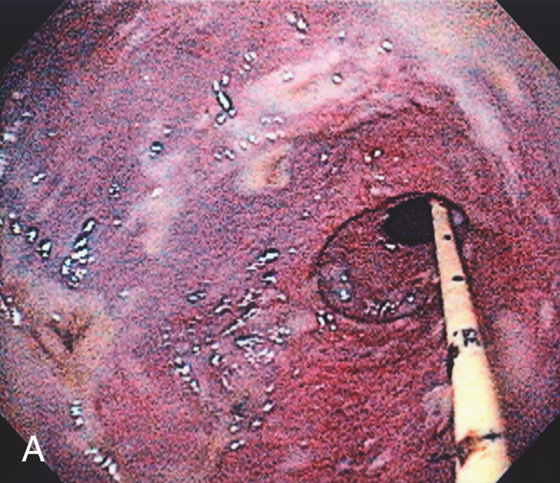

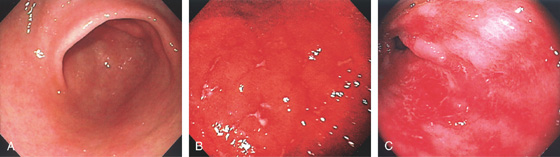

Figure 3.10 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

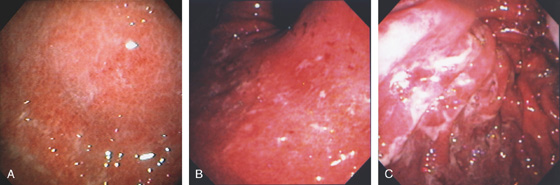

A, Severe gastritis in the gastric body, with edema, erythema, scattered subepithelial hemorrhage, and overlying exudate. B, C, Severe gastritis manifested by erythema and exudate.

Figure 3.10 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

D, Gastric body mucosa with severe acute and chronic inflammation and crypt abscess formation.

E-F, Gastric body mucosa with severe acute and chronic inflammation and crypt abscess formation.

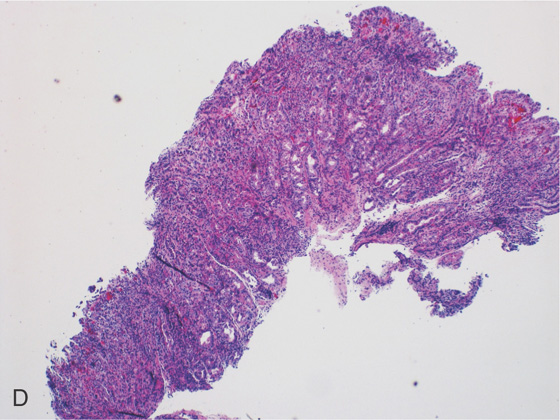

Figure 3.11 HELICOBACTER PYLORI ANTRAL GASTRITIS

A, A mottled appearance of the gastric antrum. The area of bleeding represents extreme friability.

B, Prominent chronic active gastritis. The pyloric glands are infiltrated by neutrophils, and increased numbers of chronic inflammatory cells are in the lamina propria. C, Close-up view of a gastric gland reveals infiltration with neutrophils. Organisms compatible with Helicobacter pylori are seen on the luminal surface of the epithelial cells.

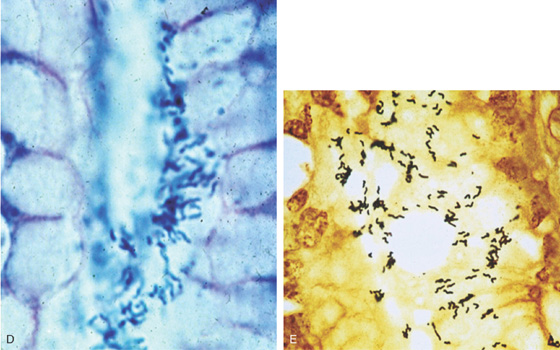

Figure 3.11 HELICOBACTER PYLORI ANTRAL GASTRITIS

Special stains with Giemsa (D) and silver stain (E) better highlight the organism.

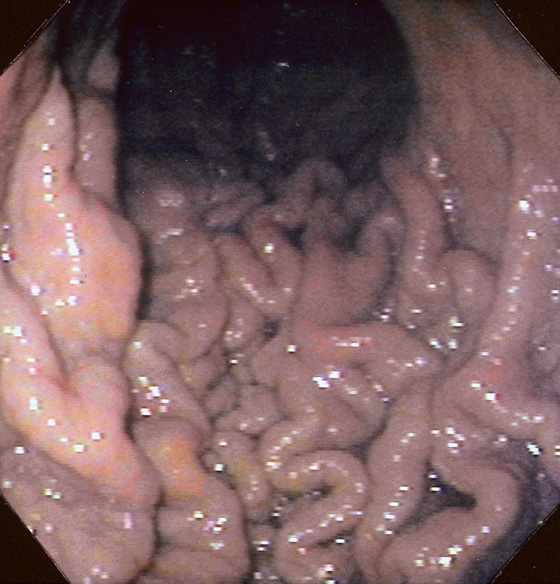

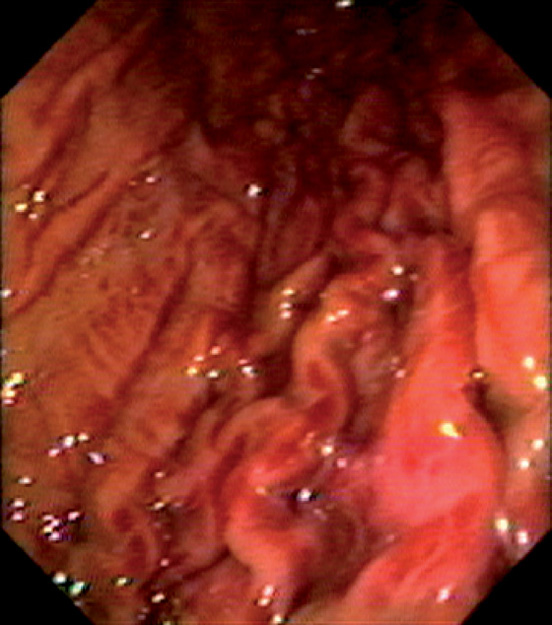

Figure 3.12 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

Marked prominence of the gastric rugae.

Helicobacter pylori Gastritis (Figure 3.12)

Ménétrier’s disease

Infiltrating neoplasms

Lymphoma

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

Mastocytosis

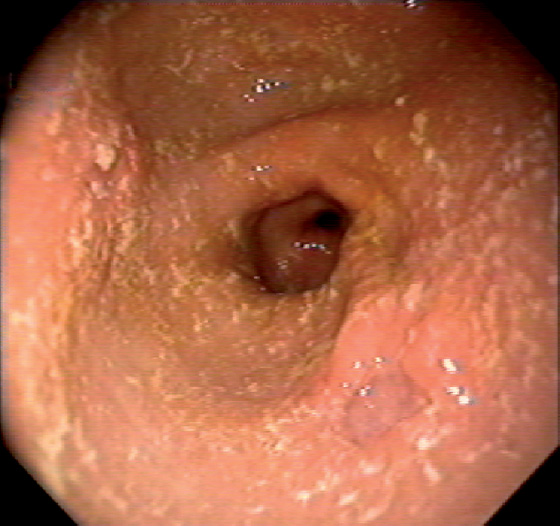

Figure 3.13 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

The areae gastricae are prominent and there is associated subepithelial hemorrhage.

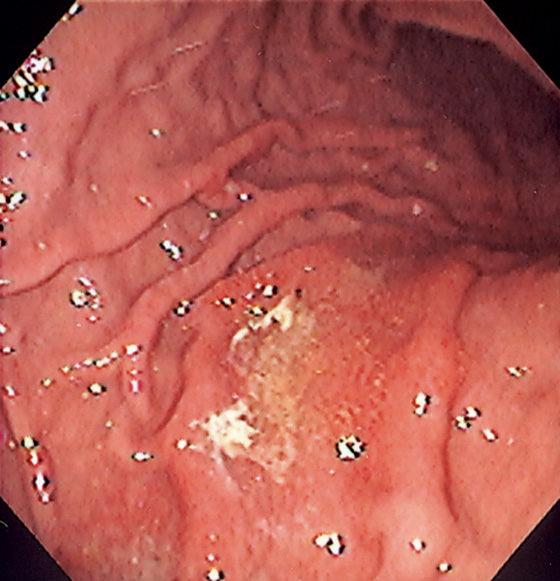

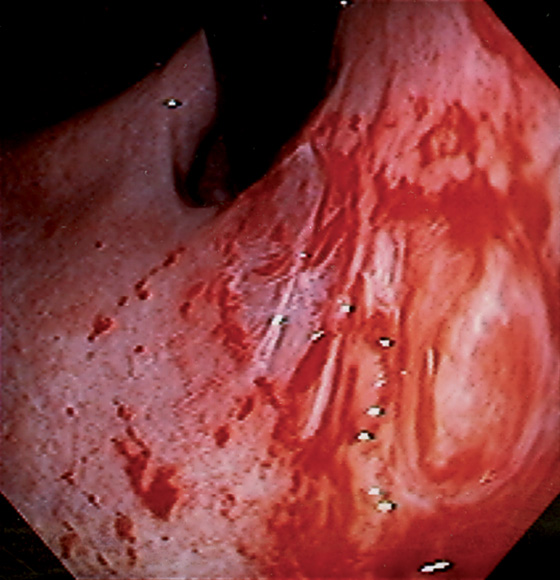

Figure 3.14 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS WITH SCARRING

End-stage H. pylori gastritis with atrophy and evidence of prior scarring, with “ghosts” of prior mucosal injury seen as linear areas of scarring with surrounding subepithelial hemorrhage and edema.

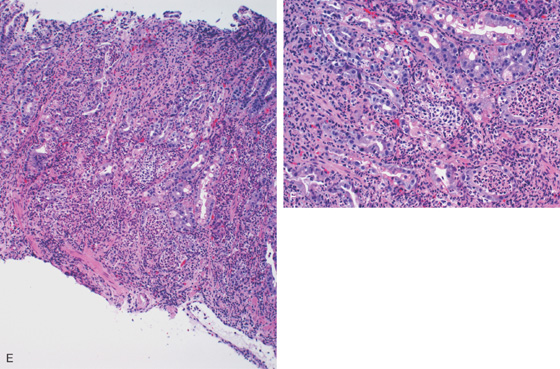

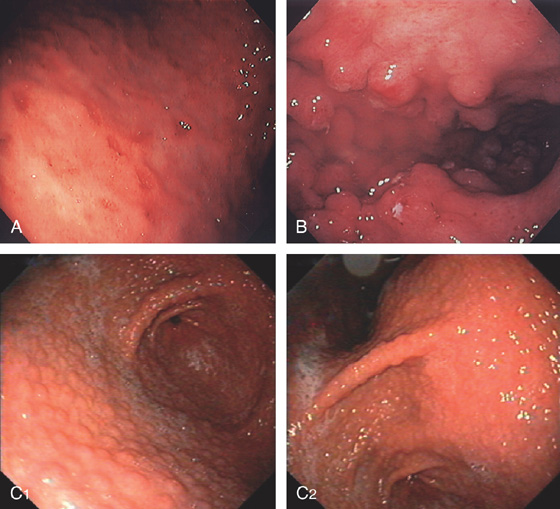

Figure 3.15 LYMPHOCYTIC GASTRITIS

A, Multiple erosions of the gastric body. B, Multiple small polypoid lesions principally involving the gastric body. C, Diffuse nodularity of the distal (C1) and proximal (C2) stomach.

D1, Preserved architecture with an appearance of chronic gastritis. D2, Close-up shows a diffuse infiltration of lymphocytes in the mucosa.

Figure 3.16 CHEMICAL GASTRITIS

Focal area of edema with exudate in the gastric body. Biopsies showed mild inflammation with foveolar hyperplasia. Iron was also present in the specimen. These findings suggest gastropathy induced by pills, in this case, iron.

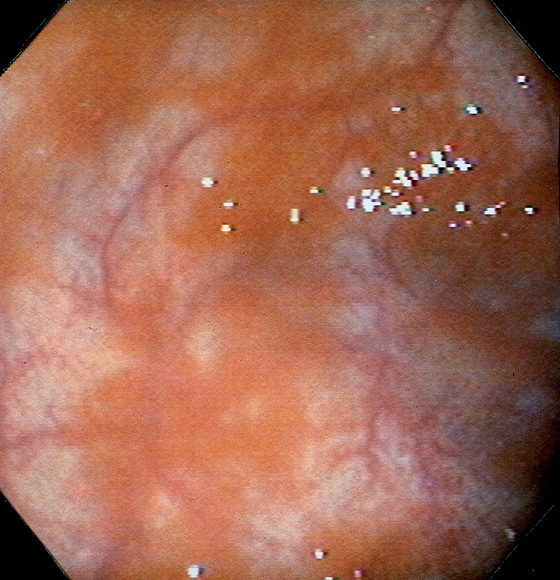

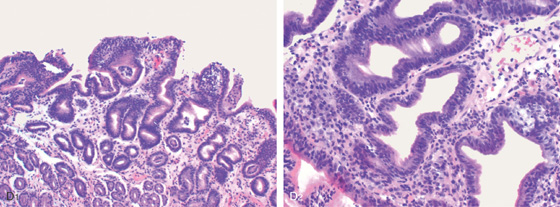

Figure 3.17 GASTRIC ATROPHY

A, The end result of long-standing Helicobacter pylori gastritis is atrophy. The gastric rugae are completely absent, with blood vessels easily seen throughout the gastric body and antrum. B, Narrow band imaging highlights the underlying vasculature.

C, Gastric atrophy and chronic gastritis.

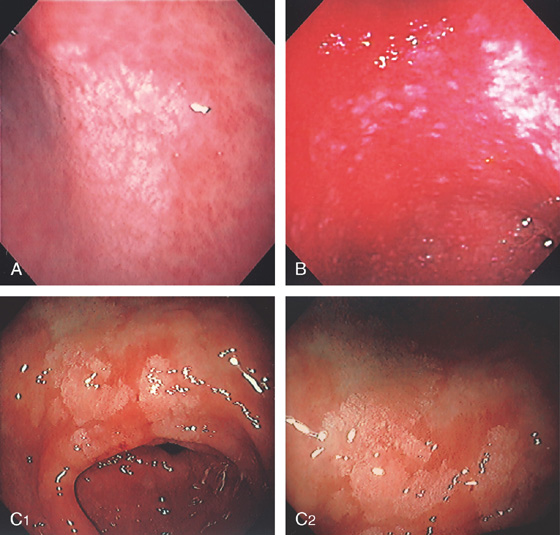

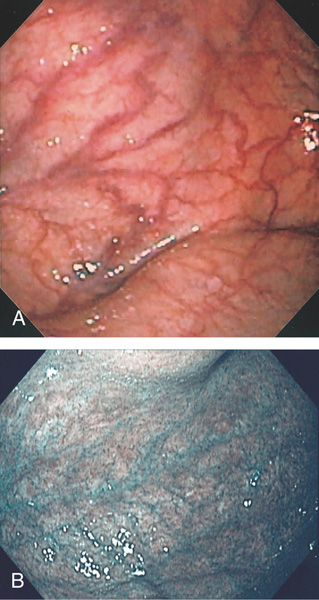

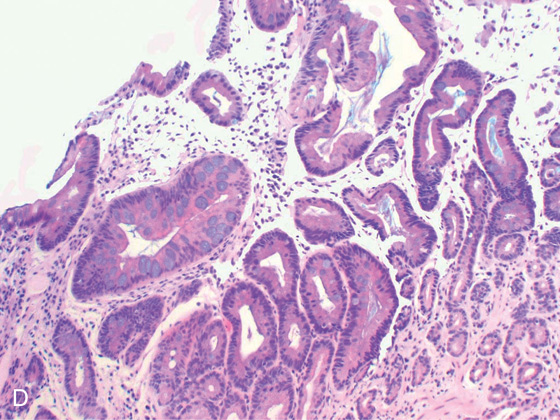

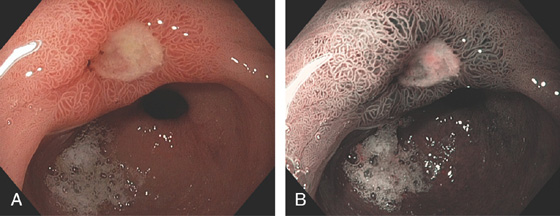

Figure 3.18 INTESTINAL METAPLASIA

A, Focal white plaquelike lesion of the antrum. B, Multiple white plaquelike lesions of the antrum. C1, C2, Multiple white plaquelike lesions with a verrucous appearance in the gastric antrum. Note that the surrounding gastric mucosa is relatively atrophic.

D, Numerous goblet cells are present, confirming the diagnosis.

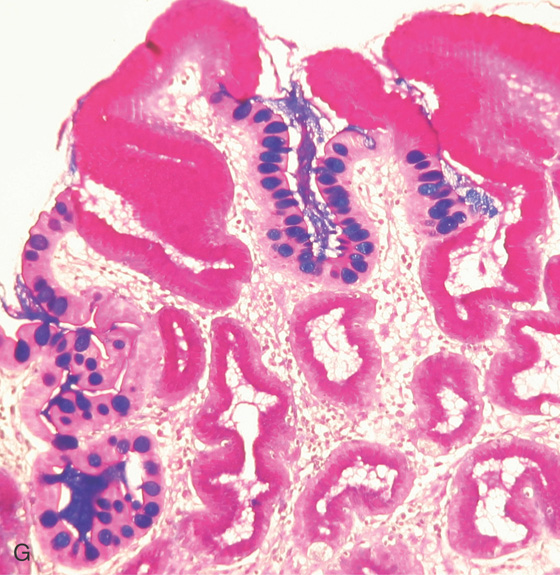

Figure 3.18 INTESTINAL METAPLASIA INTESTINAL METAPLASIA PATHOLOGY

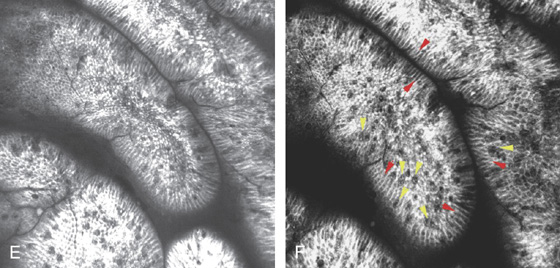

E, Intestinal metaplasia as seen by optical coherence tomography. F, The goblet cells stain and brush border are visible (red arrows indicate brush border; yellow arrows indicate goblet cells).

G, Periodic acid-Schiff stain highlights the goblet cells. (F courtesy Cristian Gheorge, MD.)

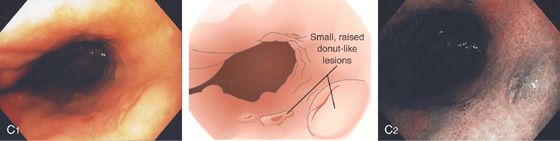

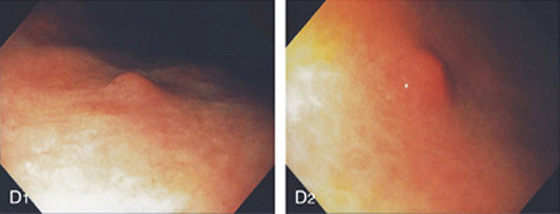

Figure 3.19 PERNICIOUS ANEMIA

A, Marked gastric atrophy with absent rugal folds and prominent vascular pattern. B, Multiple small polyps in the proximal body and fundus, which on biopsy were carcinoid tumors.

C1, Small, raised, donutlike lesions in the gastric body. C2, Appearance on narrow band imaging.

D1, D2, Small polyp on a background of gastric atrophy.

E1, E2, Appearance on narrow band imaging. These lesions were small carcinoid tumors.

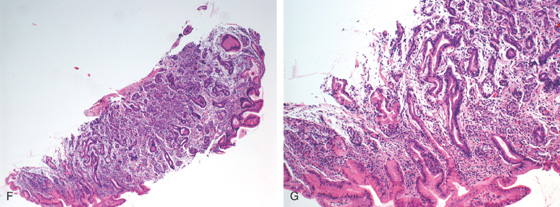

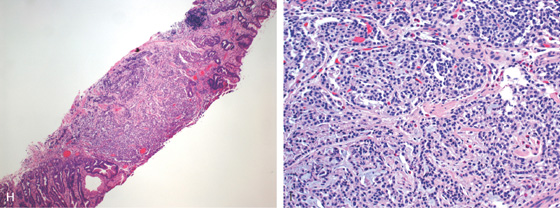

Figure 3.19 PERNICIOUS ANEMIA

F, G, The mucosa is atrophic with decreased or absent parietal and chief cells, as well as presence of intestinal metaplasia.

H, At low-power view, a microcarcinoid tumor is shown. I, Enterochromaffin cells are seen in the mucosa.

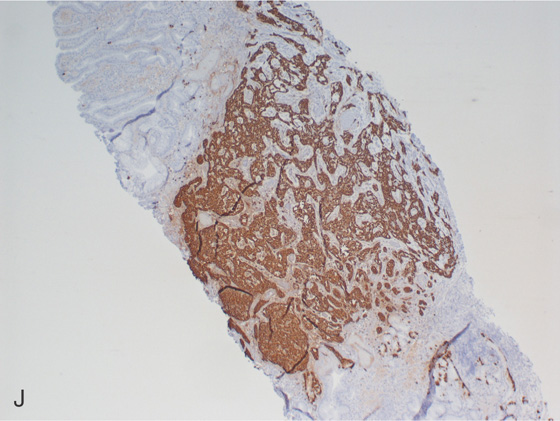

J, Chromogranin staining highlights the neuroendocrine tumor.

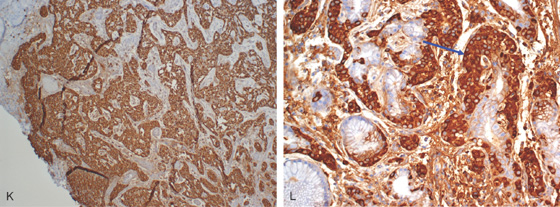

K, Chromogranin staining highlights the neuroendocrine tumor. L, Enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia/dysplasia at the base of the gland (blue arrow).

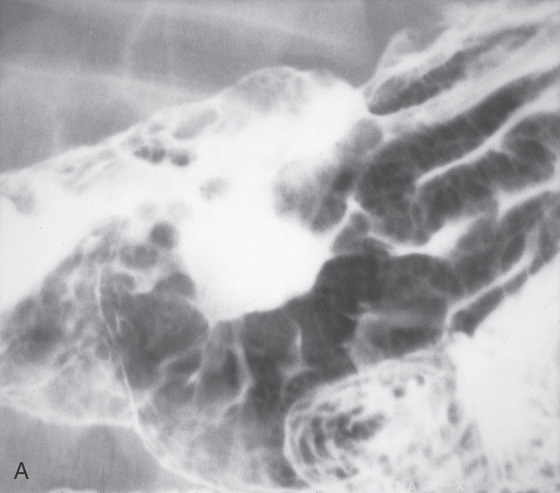

Figure 3.20 SYPHILIS

A, Large gastric ulceration, with prominent irregular rugae radiating to the lesion.

B, Irregularly shaped ulceration on the angularis, with nodularity of the ulcer rim.

Figure 3.20 SYPHILIS

C, Severe chronic inflammation composed primarily of plasma cells. A prominent plasmacytic infiltrate in a patient with positive syphilis serology is suggestive of gastric infection. D, Silver stain for spirochetes demonstrates multiple organisms.

E, Hyperpigmented lesions on the hands (E1) and feet (E2) are typical for secondary syphilis.

Figure 3.21 FOCAL CYTOMEGALOVIRUS GASTRITIS

Multiple round, erythematous, raised lesions in the gastric body and antrum. The remainder of the antrum and body is normal.

Figure 3.22 CYTOMEGALOVIRUS (CMV) GASTRITIS

A, Patchy subepithelial hemorrhage in the peripyloric area. B, Multiple focal areas of subepithelial hemorrhage in a “halo” pattern.

C1, Numerous inclusions typical for CMV. C2, High-power view shows many intranuclear inclusions.

Figure 3.23 DIFFUSE SEVERE CYTOMEGALOVIRUS GASTRITIS

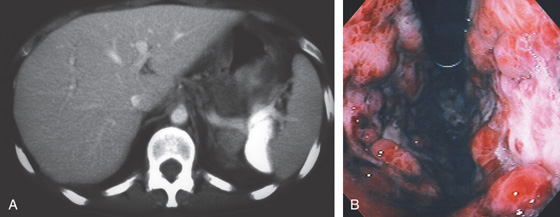

A, The stomach wall is markedly thickened, with hypodense areas suggesting necrosis. B, Retroflex view demonstrates nodularity and subepithelial hemorrhage. Diffuse ulceration is seen on the lesser curve.

C1, Marked edema and hemorrhage are present in the lamina propria. The pronounced edema produces the striking nodularity and areae gastricae pattern. C2, Multiple intranuclear inclusions characteristic of cytomegalovirus cytopathic effect.

Figure 3.24 CYTOMEGALOVIRUS ULCER

Well-circumscribed, clean-based ulcer in the posterior antrum. The surrounding mucosa is normal.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Cytomegalovirus Ulcer (Figure 3.24)

Peptic ulcer

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced ulcer

Ischemia caused by vasculitis

Malignancy

Other infections

Figure 3.25 CYTOMEGALOVIRUS ANTRAL ULCER

Large, deep ulcer. The pylorus is seen at the top left, indicating the depth of the lesion.

Figure 3.26 MYCOBACTERIUM AVIUM COMPLEX GASTRITIS

Diffuse gastritis with petechial hemorrhages and a well-circumscribed, small nodular lesion with central erosion.

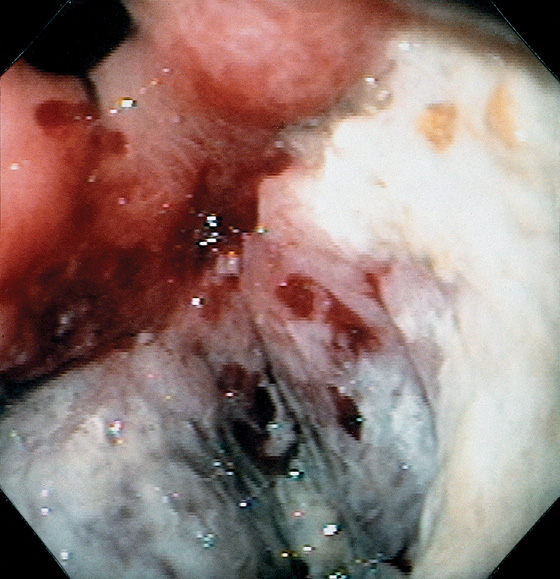

Figure 3.27 GASTRIC MUCORMYCOSIS

A, Erosion and exudate of the gastric antrum with a dark hue to the mucosa. A feeding tube is present.

B1, B2, Multiple fungal forms in the submucosa.

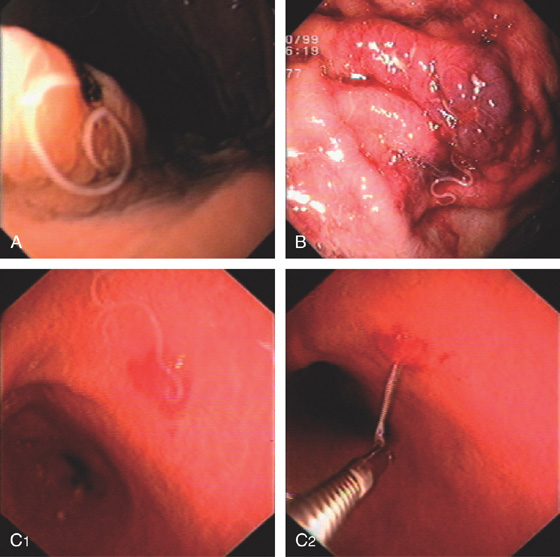

Figure 3.28 ANISAKIASIS

Single larva entering the gastric mucosa with focal area of old bleeding (A) or subepithelial hemorrhage (B). C, The larva is being removed with biopsy forceps (C1, C2).

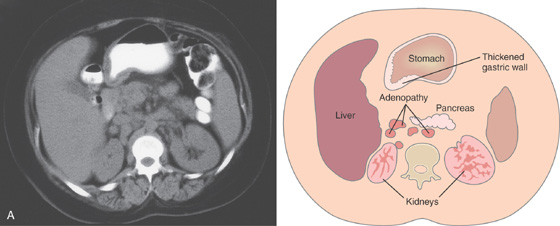

Figure 3.29 SARCOID GASTRITIS

A, Marked thickening of the gastric body and antrum. Multiple retroperitoneal nodes are present. Fullness along the lateral margin of the pancreatic head and retrocaval portion of the retroperitoneum suggests adenopathy.

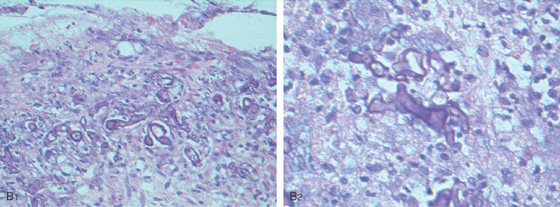

Figure 3.29 SARCOID GASTRITIS

B, Multiple erosions, some having an unusual stellate appearance, in the gastric body (B1), angularis and proximal lesser curve (B2), and antrum (B3, B4). The antrum has a yellow-orange discoloration and a mottled appearance; the mucosa is friable.

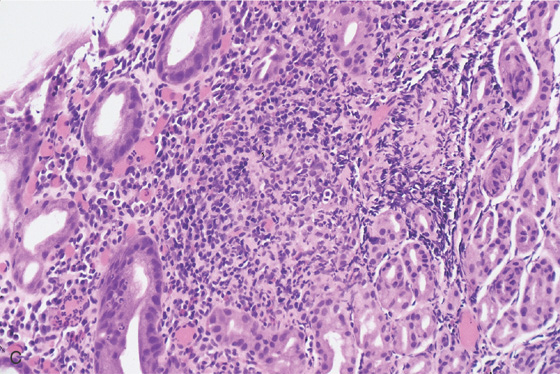

C, Noncaseating granuloma in the lamina propria. Special stains for other causes of granulomatous gastritis, including mycobacterial and fungal organisms, were negative.

Figure 3.30 SARCOID GASTRITIS

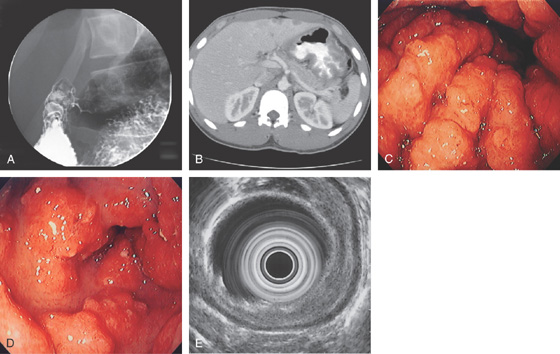

A, Nodular fold thickening of the gastric antrum, duodenal bulb, and postbulbar duodenum. B, Marked thickening of the gastric wall. C, Marked nodularity and thickening of the folds in the gastric body. D, Nodular lesions in the gastric antrum. E, The thickening of the gastric wall is limited to the mucosal layer by endoscopic ultrasonography.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Sarcoid Gastritis (Figure 3.30)

Gastric adenocarcinoma

Lymphoma

Metastatic tumor resulting in linitis plastica

Figure 3.31 ALCOHOL-INDUCED GASTROPATHY

A, The gastric rugae are edematous, with fresh blood seen under the mucosal surface; the overlying mucosa is smooth. B, A prominent band of extravasated erythrocytes is present, associated with edema of the lamina propria. No histologic evidence of gastritis is present.

Figure 3.32 ASPIRIN-INDUCED GASTROPATHY

A, Multiple scattered petechial hemorrhages, with normal-appearing intervening mucosa. B, Subepithelial hemorrhage is present without an associated inflammatory process.

Figure 3.33 ASPIRIN-INDUCED GASTROPATHY

Multiple areas of fresh hemorrhage in the distal gastric body and antrum.

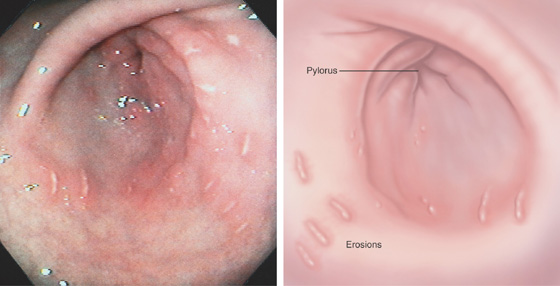

Figure 3.34 NONSTEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY DRUG (NSAID)-INDUCED EROSIVE GASTROPATHY

Multiple linear erosions surrounded by a halo of erythema in the antrum, with normal intervening mucosa. Antral disease is the typical location for NSAID-induced injury.

Figure 3.35 NONSTEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY DRUG (NSAID)-INDUCED GASTROPATHY

A, B, Multiple small antral erosions with erythematous halos.

Figure 3.36 PORTAL HYPERTENSIVE GASTROPATHY

A, Mild disease is manifested by prominence of the areae gastricae, with areas of erythema and subepithelial hemorrhage. This appearance is not pathognomonic but may be noted with other disorders inducing mucosal edema, such as Helicobacter pylori gastritis. B, Marked prominence of the areae gastricae. C, Severe gastropathy with diffuse subepithelial hemorrhage in a snakeskin pattern. D, Prominent edema of the lamina propria with multiple congested blood vessels. No histologic evidence of gastritis is seen.

Figure 3.37 THROMBOTIC THROMBOCYTOPENIC PURPURA

Multiple areas of subepithelial hemorrhage throughout the gastric body.

Figure 3.38 NASOGASTRIC TUBE TRAUMA

A, Multiple well-circumscribed, hemorrhagic lesions extending down the gastric body to the antrum. B, The reddish color resembles ectasias. C, With progression, erosions may result, and then ultimately ulcers (D).

Figure 3.39 GRAFT-VERSUS-HOST DISEASE

A, Normal-appearing gastric antrum. Biopsies confirmed mild graft-versus-host disease. The mucosa may appear normal in mild disease, emphasizing the importance of mucosal biopsies. B, Marked erythema of the gastric body with multiple erosions. C, Sloughing of the antral mucosa leaving a shiny erythematous appearance.

Figure 3.40 GASTRIC TEAR

This fresh tear occurred during endoscopy in a patient with pronounced gastric atrophy. This could occur from the endoscope in addition to air insufflation and retching.

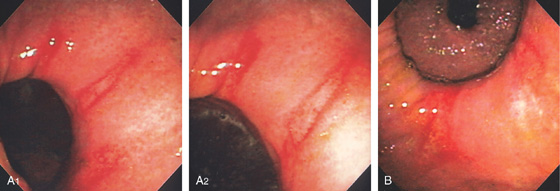

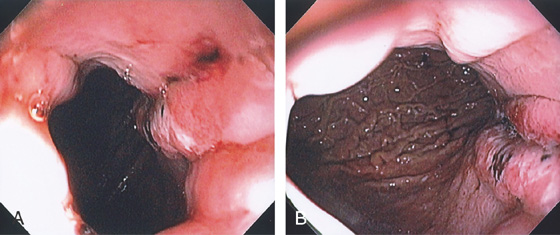

Figure 3.41 GASTRIC MALLORY-WEISS TEAR

A, Tear begins distal to the gastroesophageal (GE) junction. B, Note the extent of the lesion down the lesser curvature.

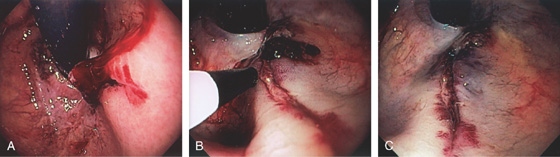

Figure 3.42 BLEEDING GASTRIC MALLORY-WEISS TEAR

A, Retroflex view shows active bleeding from a linear lesion just distal to the GE junction. B, Epinephrine injection results in blanching of the mucosa. C, Blanching is apparent around the tear with resultant hemostasis.

Figure 3.42 BLEEDING GASTRIC MALLORY-WEISS TEAR CLIPPING OF A GASTRIC MALLORY-WEISS TEAR

D, E, Tear just below a ring at the gastroesophageal junction. F, Clips applied to the lesion resulting in hemostasis.

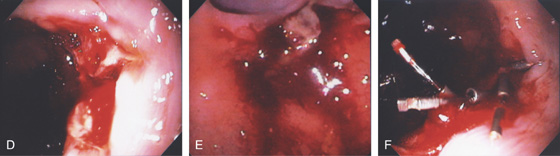

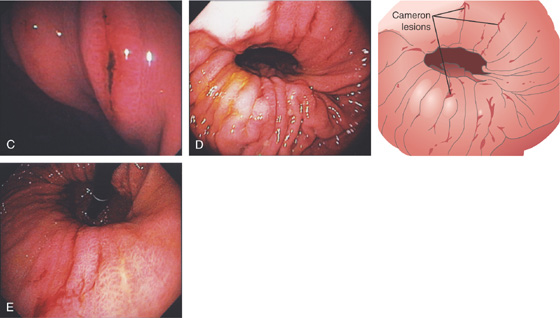

Figure 3.43 CAMERON LESIONS

Multiple erosions straddle a large hiatal hernia as shown on antegrade (A1, A2) and retrograde (B) views.

C, Several lesions on the gastric folds, one of which has a linear black eschar. Multiple linear areas of fresh hemorrhage on the diaphragmatic hiatus on antegrade (D) and retrograde (E) views.

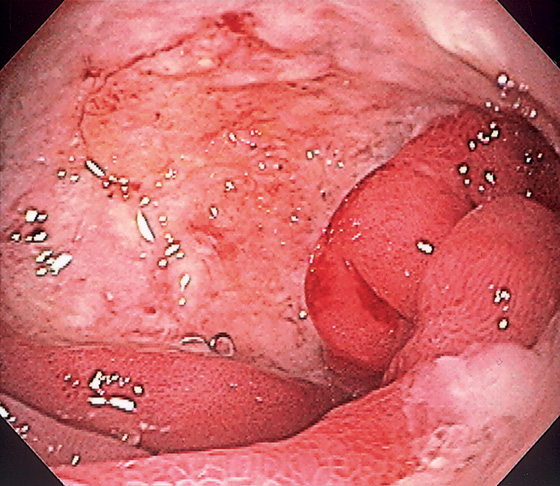

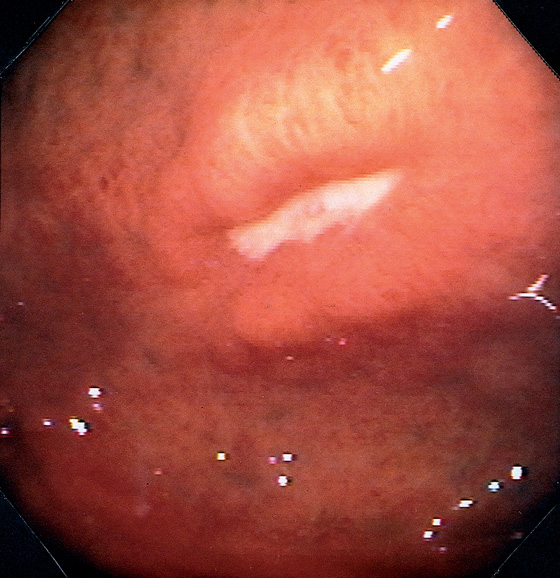

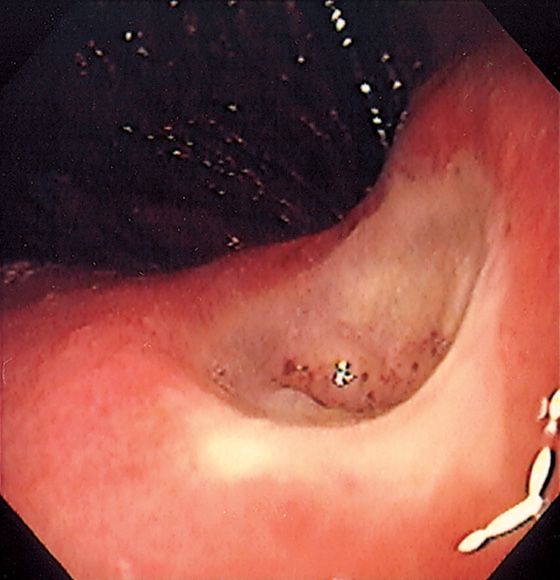

Figure 3.44 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Linear ulceration of the gastric cardia. The surrounding mucosa is erythematous, with subepithelial hemorrhages.

Figure 3.45 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Ulcer in the fundus with an elevated appearance.

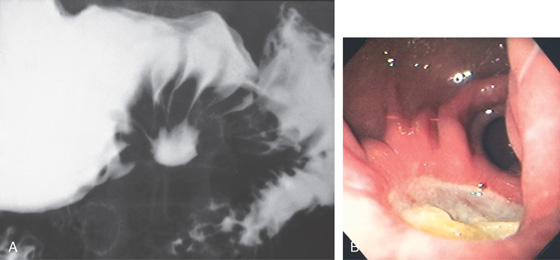

Figure 3.46 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

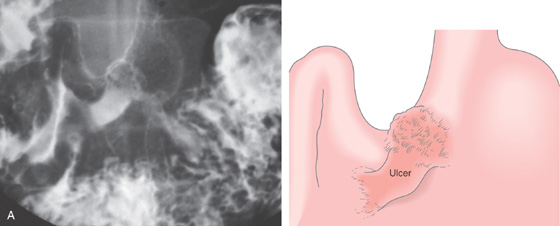

A, Elbow-shaped ulceration along the lesser curvature. The proximal portion of the ulcer has air contrast, whereas the distal portion has barium pooling.

B, The shape of the large ulceration on the angularis corresponds to the radiograph. Additional ulcerations are present anteriorly. Multiple black spots (stigmata of hemorrhage) are present in the ulcer base, despite the absence of clinical bleeding.

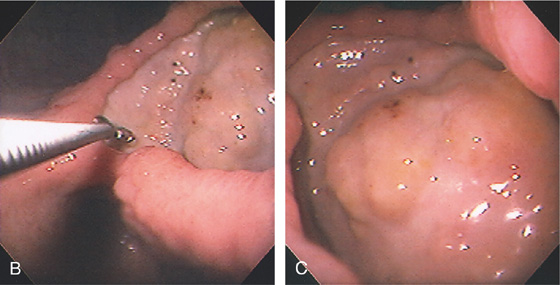

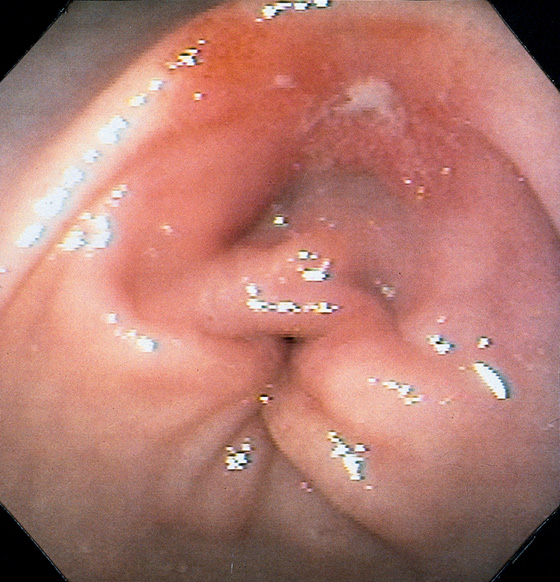

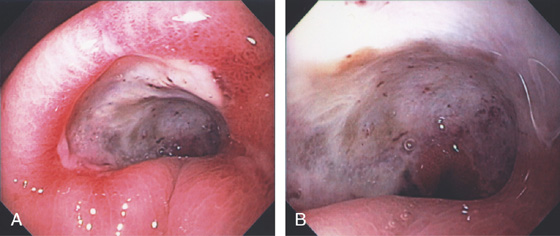

Figure 3.47 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

A, Ulcer on the angularis projecting away from the gastric lumen, suggesting a benign lesion. B, Large benign-appearing ulcer on the angularis. Exudate covers the base. The ulcer has a symmetrical punched-out appearance, and no abnormal-appearing rugal folds appear around the lesion.

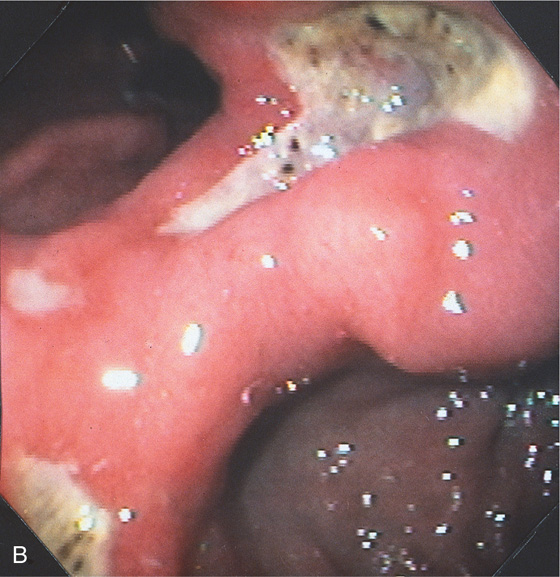

Figure 3.48 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

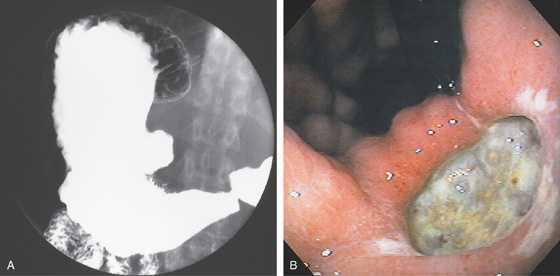

A, Large ulcer projecting off the lesser curve at the angularis. An ulcer collar is present, suggesting a benign lesion.

B, Large, well-circumscribed ulcer on the angularis seen by retroflexion. The size of the ulcer is evident by comparison with the open biopsy forceps (6 mm in width). C, Close-up shows the size and depth of the lesion. The base has a nodular appearance suggestive of involvement of surrounding abdominal structures.

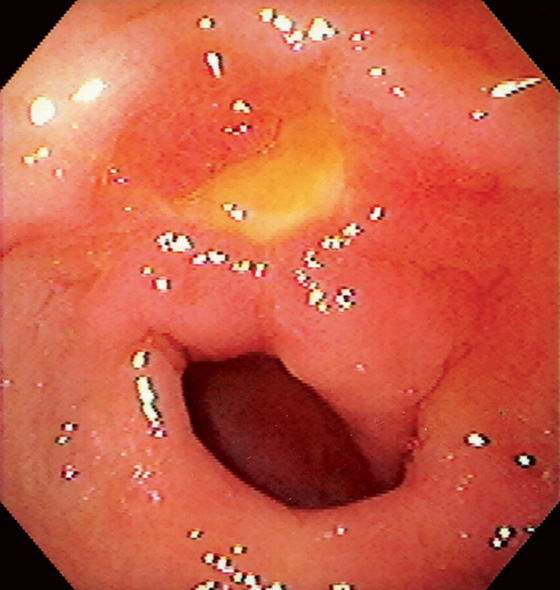

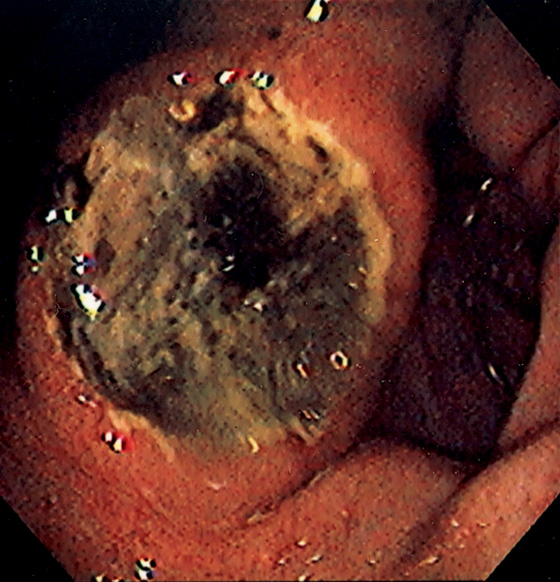

Figure 3.49 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

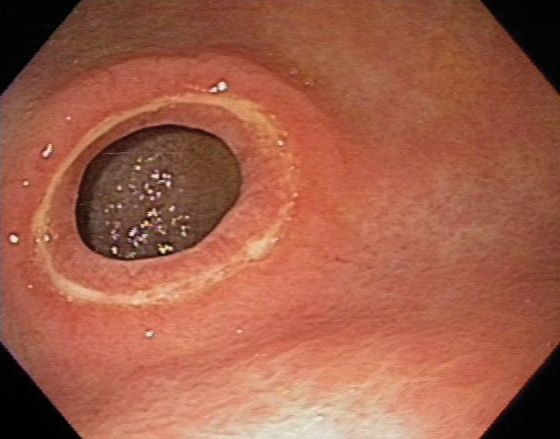

Well-circumscribed ulcer of moderate depth on the angularis. The borders are smooth and the ulcer is relatively symmetrical, all of which are features suggestive of a benign as compared with a malignant ulcer.

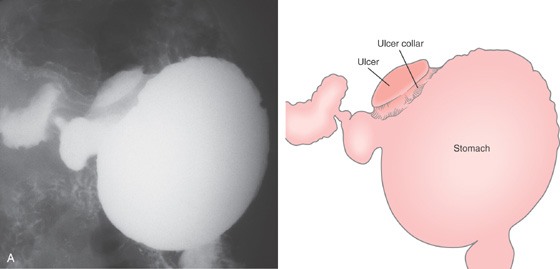

Figure 3.50 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

A, Benign-appearing gastric ulcer as demonstrated by the well-circumscribed nature of the barium collection (ulcer), with multiple smooth folds radiating to the ulcer. A smooth, round, homogeneous mound of edema surrounding the crater, with smooth radiating folds extending all the way to the crater, suggests a benign ulcer. Other signs of a benign ulcer include Hampton’s line or an ulcer collar and projection beyond the lumen. B, Large, well-circumscribed antral ulceration, with folds radiating to the ulcer base.

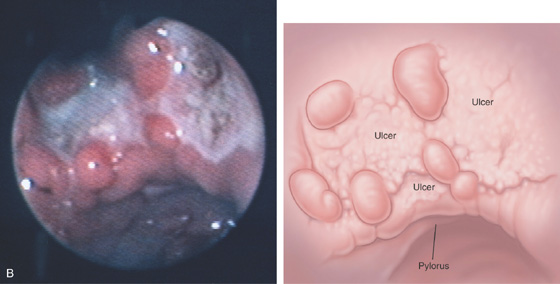

Figure 3.51 PERIPYLORIC ULCER

Circumferential ulceration surrounds the pylorus.

Figure 3.52 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Small prepyloric ulceration, with surrounding erythema superior and posterior to the pylorus. There is cicatrization of the stomach toward the ulceration.

Figure 3.53 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Bile-stained peripyloric ulcer.

Figure 3.54 ANTRAL ULCER

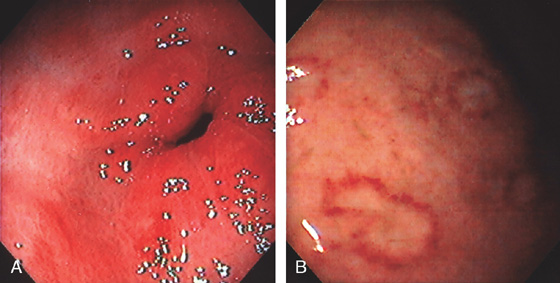

Well-circumscribed, benign-appearing ulcer in the antrum anteriorly on high-resolution (A) and narrow band imaging (B).

Figure 3.55 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Large deep ulceration at the pylorus (A, B).

Figure 3.56 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Large ulceration with a heaped-up appearance in the distal gastric body. The raised appearance is unusual and suggests primary or metastatic malignancy. Follow-up endoscopy after therapy showed ulcer healing.

Benign Gastric Ulcer (Figure 3.56)

Adenocarcinoma

Metastatic carcinoma

Melanoma

Breast carcinoma

Lung carcinoma

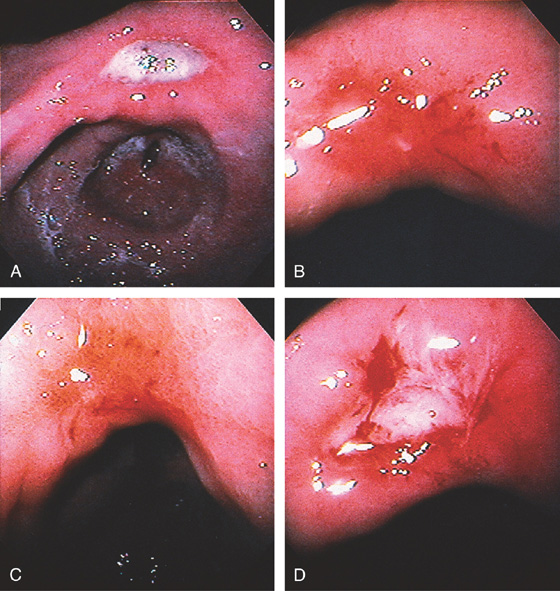

Figure 3.57 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Deep, well-circumscribed, benign-appearing ulcer on the angularis (A). One month after standard ulcer therapy, the ulceration has almost completely healed; there is a small central erosion, deformity, and diffuse erythema and friability (B). After 2 months of therapy, complete healing is seen; friability is still present (C). One month after discontinuation of therapy, the ulcer has recurred in the same location and with endoscopic characteristics similar to those of the initial ulcer (D).

Figure 3.58 BENIGN ULCER IN GASTRIC POUCH

Hemicircumferential ulceration in a small gastric pouch after gastric bypass.

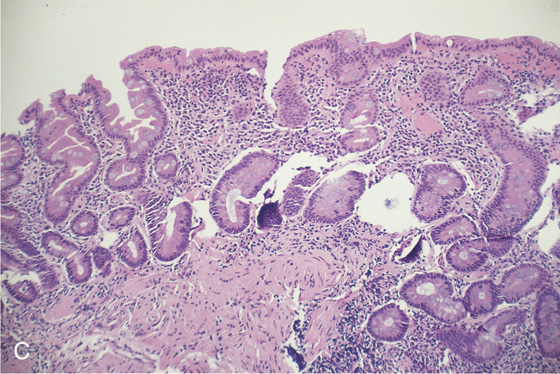

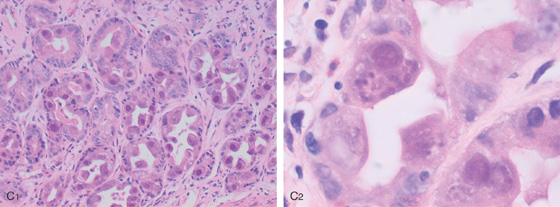

Figure 3.59 HISTOLOGY OF AN ULCER BASE

Characteristic histopathologic changes of an ulcer base, including acute and chronic inflammatory cells, fibroplasia, and neovascularization. Careful examination must be performed to differentiate reactive atypia from neoplasia in this area.

Figure 3.60 ULCER SCAR

Retraction of the mucosa with radiating folds and erythema typical for an area of prior large ulceration.

Figure 3.61 NONSTEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY DRUG (NSAID)-INDUCED GASTRIC ULCERS

A, Numerous well-circumscribed ulcers involving the gastric body and fundus seen on retroflexion. B, Multiple well-circumscribed ulcerations of the antrum and pyloric canal. C, Solitary chronic-appearing ulcer of moderate depth on the posterior wall of the antrum. Note the xanthomatous lesion at the pylorus. D, Large, triangular-shaped ulcer in the distal antrum.

Figure 3.62 PYLORIC STENOSIS CAUSED BY ULCER

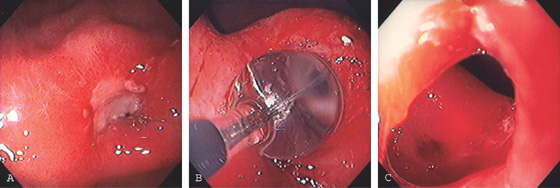

A, Exudate and edema at the pylorus. The opening is not visible. B, A balloon was inflated across the ulceration. C, The luminal caliber is now much improved.

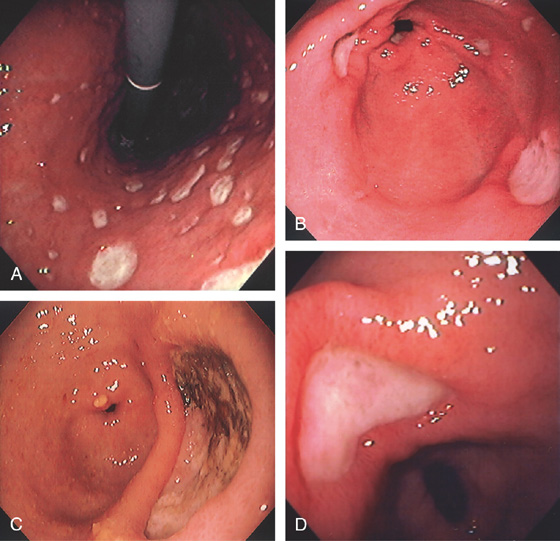

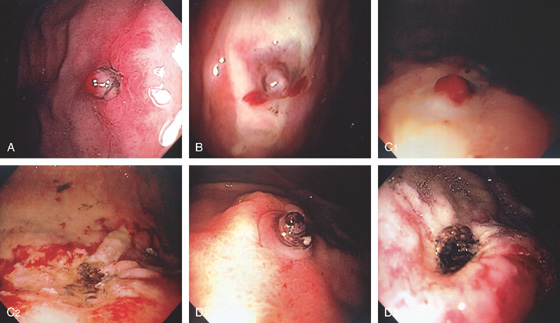

Figure 3.63 BLEEDING GASTRIC ULCER

A, Large gastric ulcer with a central arterial defect. Blood is spurting in a pulsatile fashion, characteristic of an arterial bleeding source. B, A heater probe is applied with firm pressure to the defect, causing cessation of bleeding. C, After multiple pulses of energy and washing, the defect is coagulated, as represented by the black areas. With washing, the large size of the ulceration is evident.

Figure 3.64 BLEEDING GASTRIC ULCER

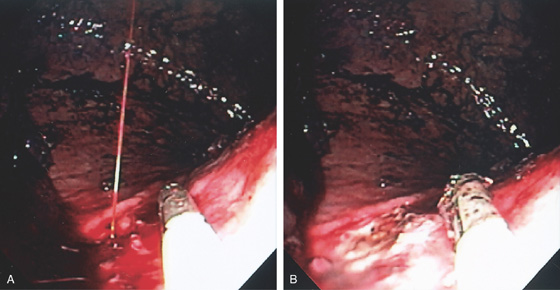

A, Arterial jet pulsating from an area in the proximal gastric body. The heater probe is alongside the lesion. B, Thermal therapy was then applied to the area, resulting in a black eschar and hemostasis.

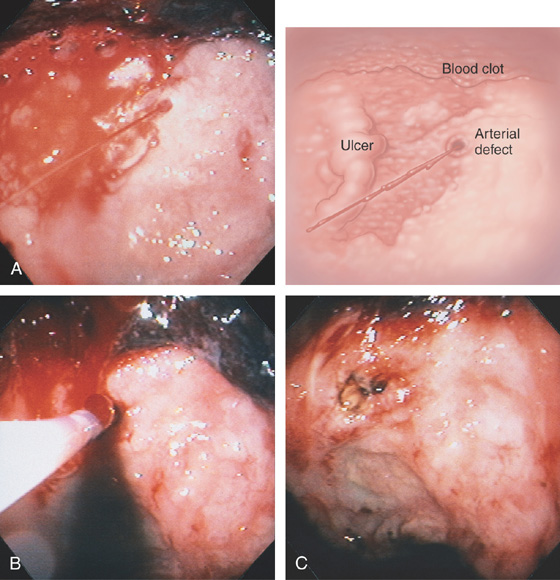

Figure 3.65 BLEEDING GASTRIC ULCER

A, Large ulceration with fresh bleeding and an actively pulsating jet. B, Epinephrine was injected and the heater probe used to ablate the area, resulting in a large eschar (C). Now that the bleeding has ceased, the extensiveness of the ulcer can be identified (D).

Figure 3.66 GASTRIC ULCER WITH VISIBLE VESSEL

A, Large ulcer on the angularis with central raised lesion. B, Fleshy visible vessel in the center of the ulcer.

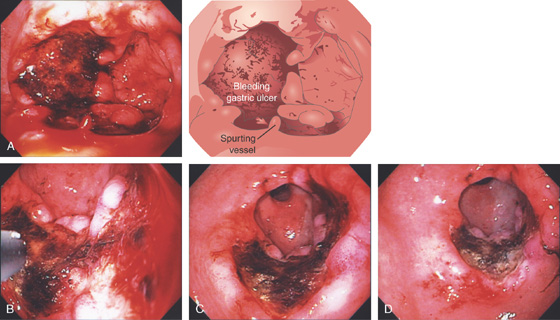

Figure 3.67 GASTRIC ULCER WITH VISIBLE VESSEL

A, Nipple-like projection emanating from a small mucosal defect. B, Fleshy nipple-like projection from a superficial ulceration. C1, Linear ulcer with raised area with reddish covering. C2, After thermal therapy, the vessel has been obliterated, leaving a black eschar with depth. D1, Dark nipple-like projection of the gastric body. D2,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree