Small-Intestinal Neoplasms and Carcinoid Tumors

Neoplasms of the small intestine, either benign or malignant (Table 32-1), are unusual but not rare, comprising less than 5% of all gastrointestinal tumors. Because they are uncommon and relatively inaccessible to standard diagnostic studies, the diagnosis of small-bowel tumors is sometimes delayed.

I. DIAGNOSIS

A. Clinical presentation.

Small-intestinal (SI) tumors usually occur in people over age 50. The presenting signs and symptoms are similar whether the tumors are benign or malignant. Small-bowel obstruction, either partial or complete, manifested by abdominal pain or vomiting or both, is a frequent presentation. Chronic partial obstruction may predispose to stasis and bacterial overgrowth, leading to bile acid deconjugation and malabsorption (see Chapter 31). Bleeding from the tumor or ulceration in association with the tumor also is common. Perforation of the bowel is rare. If a duodenal tumor is located in the vicinity of the ampulla of Vater, obstruction of the common bile duct may develop, resulting in biliary stasis and jaundice. Weight loss commonly accompanies malignant tumors.

The physical examination usually is nondiagnostic. Signs of small-bowel obstruction may be evident, such as a distended, tympanic abdomen and high-pitched bowel sounds. Occasionally malignant small-bowel tumors can be palpated. Stool may be positive for occult blood.

B. Laboratory and other diagnostic studies

1. Blood studies.

Anemia may develop because of blood loss or malabsorption. Hypoalbuminemia can result from malabsorption, extensive metastatic liver disease, or chronic illness. Evaluation of serum alkaline phosphatase or bilirubin levels may indicate biliary obstruction or metastatic liver disease.

2. An upright plain x-ray film of the

abdomen may show air-fluid levels in patients with small-bowel obstruction. If the obstruction is acute and does not resolve with nasogastric suction and intravenous fluids, surgery may be required without additional diagnostic testing.

3. Barium-contrast x-ray studies.

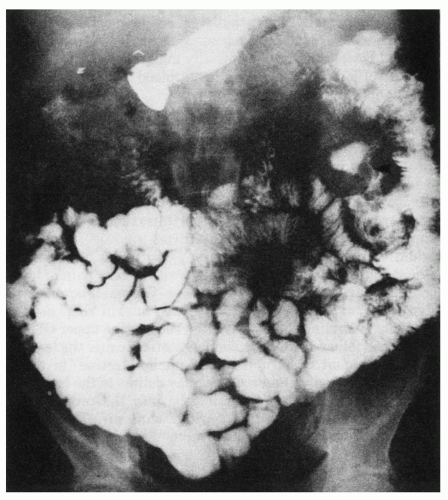

The patient who has a small-bowel tumor without frank obstruction but perhaps with colicky pain or bleeding typically undergoes barium-contrast x-ray studies. The small-bowel series may show a polypoid lesion (Fig. 32-1) or the typical “napkin ring” deformity of adenocarcinoma encircling the bowel. Often the routine upper gastrointestinal x-ray series with small-bowel follow-through is nondiagnostic because the lesion is obscured by the large amount of barium in the small intestine. In these instances, a small-bowel enema, or enteroclysis, may delineate the lesion. This procedure is performed by passing a small tube into the proximal duodenum and instilling a small amount of barium with air. This provides excellent air-barium contrast of the small intestine and enhances the diagnostic capability. For example, a diffuse nodular appearance of the mucosa on barium-contrast study may suggest lymphoma.

TABLE 32-1 Neoplasms of the Small Intestine | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

4. Endoscopy and biopsy.

If a lesion is within the duodenum, endoscopic examination and biopsy are indicated.

5. Capsule endoscopy

may be used to directly visualize SI tumors. There is risk of the capsule being retained if the tumor is large.

6. Ultrasound and computed tomography scan.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree