Benign

Peptic ulcer

NSAIDs (diaphragm disease)

Crohn’s disease

Radiation

Postinfectious (viral)

Ischemic

Radiation

Eosinophilic enteritis

Trauma

Anastomotic

Stenosing enteritis

Malignant

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (primary or recurrent)

Metastatic disease

Lymphoma

Miscellaneous

Pouch strictures

Balloon Dilation

The use of dilation will be discussed principally for management of benign diseases. In patients with prior abdominal and pelvic surgery it is particularly important to distinguish between adhesive disease and stricture disease since the former does not respond to dilation and dilation may result in perforation (Figs. 12.1, 12.2, 12.3, and 12.4).

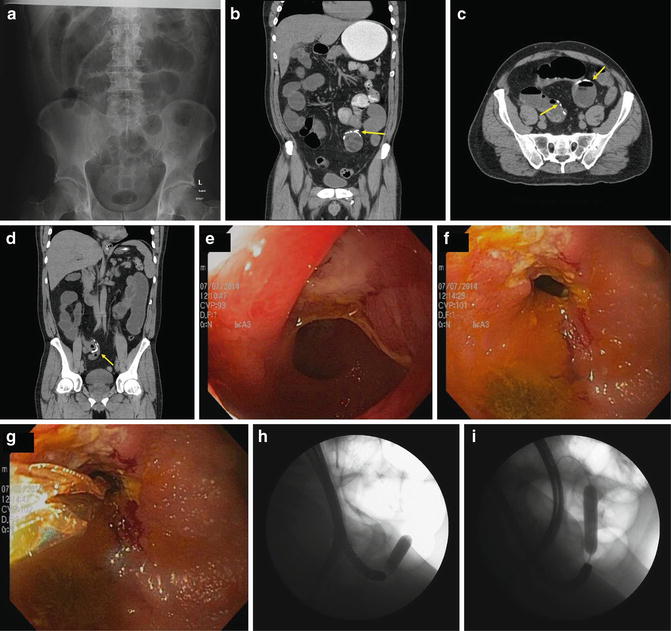

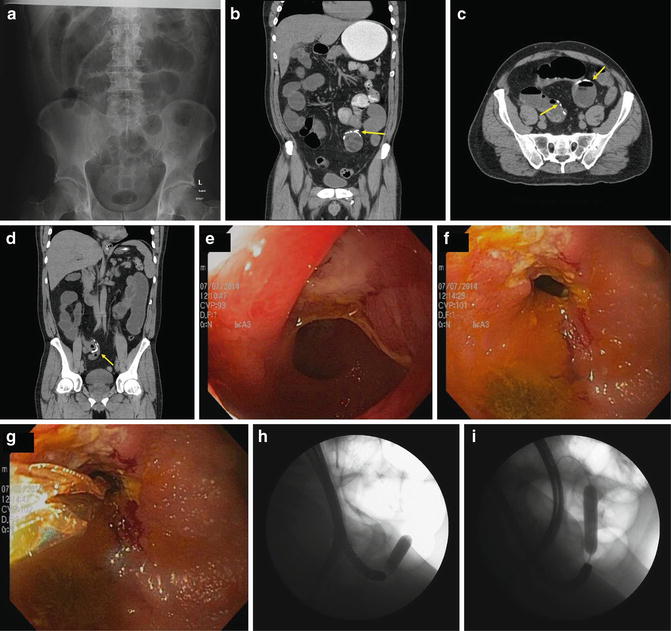

Fig. 12.1

A 60-year-old patient with multiple small-bowel resections for “adhesional strictures.” Prior to referral he had >30 hospitalizations for small-bowel obstruction. (a) Flat film demonstrates diffuse small-bowel dilation. (b–d) Arrows demonstrate multiple anastomoses with diffuse upstream small-bowel dilation. Endoscopy demonstrates (e, f ) ulcerated ileal stenoses treated with (g–i) balloon dilation

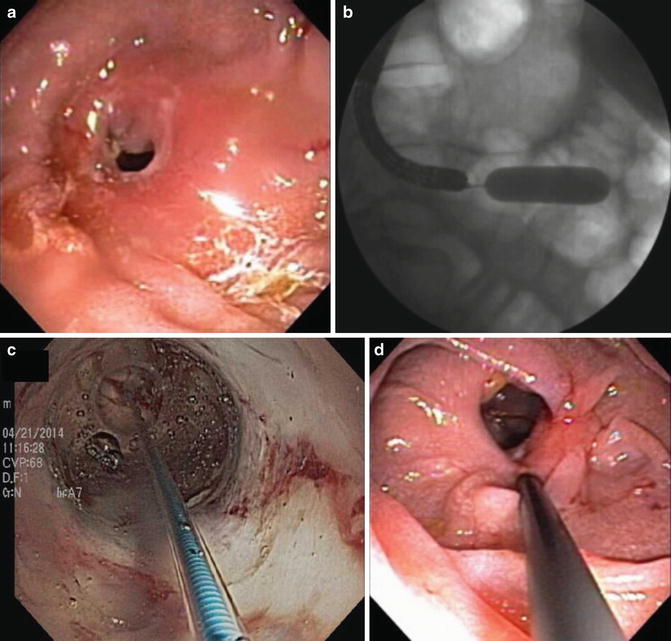

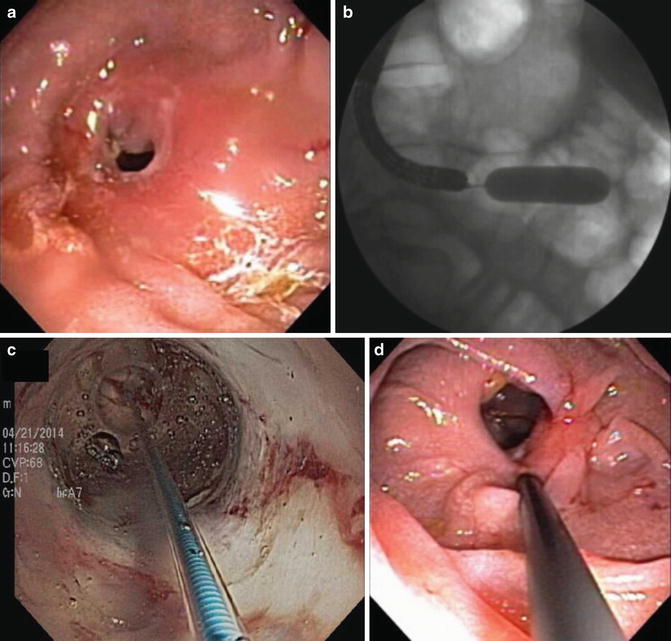

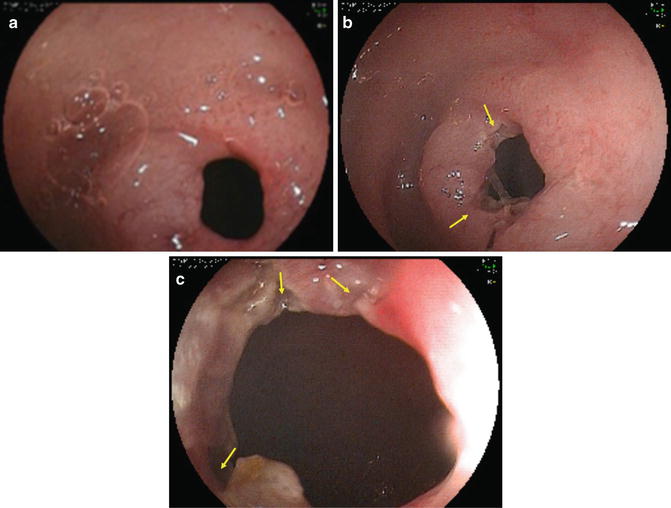

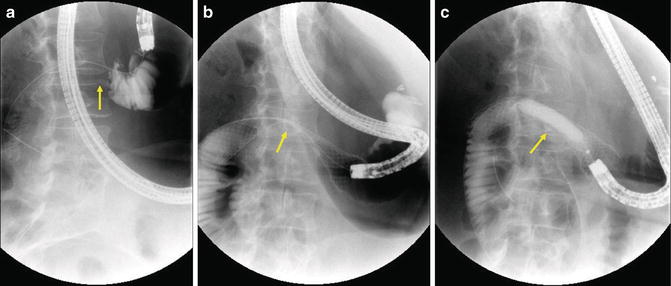

Fig. 12.2

(a) High-grade duodenal stricture in Crohn’s patient treated with (b, c) balloon dilation and (d) steroid injection

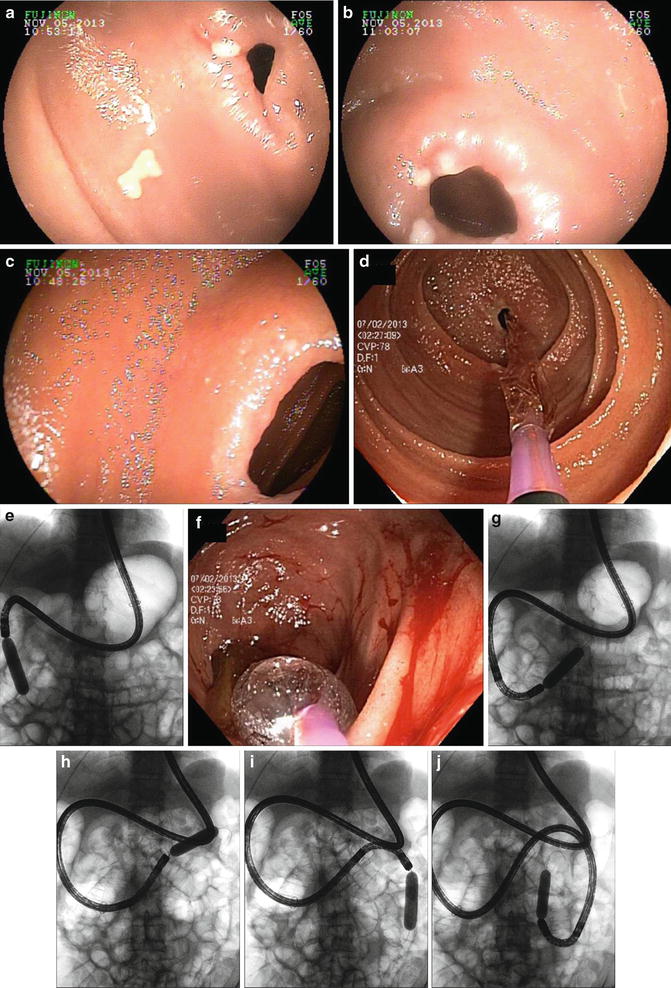

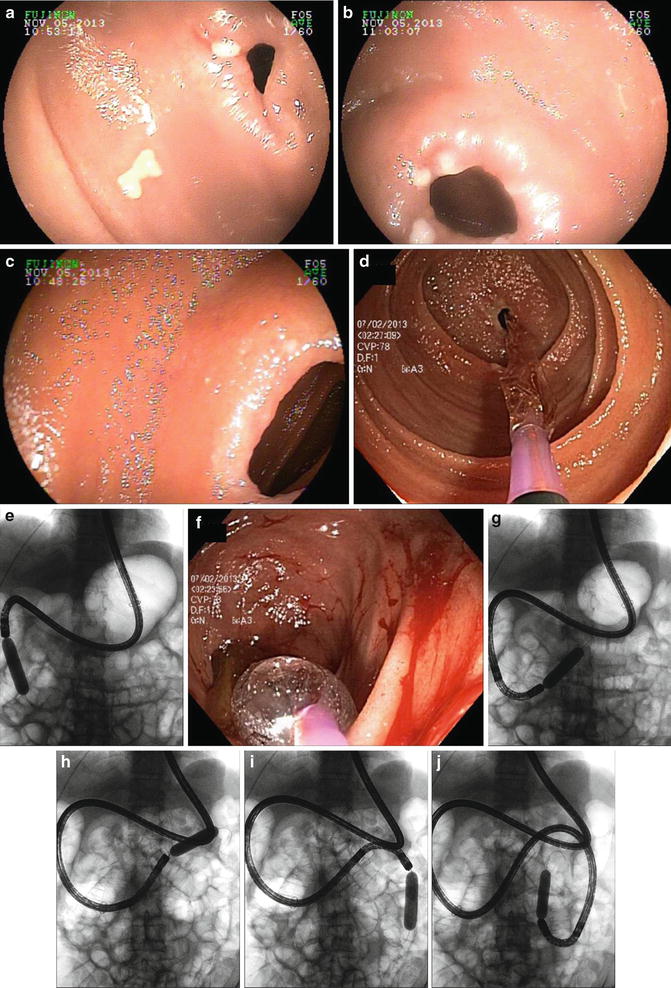

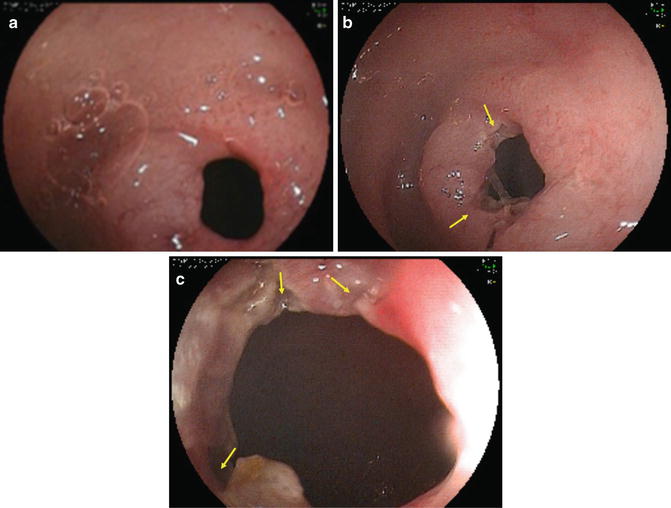

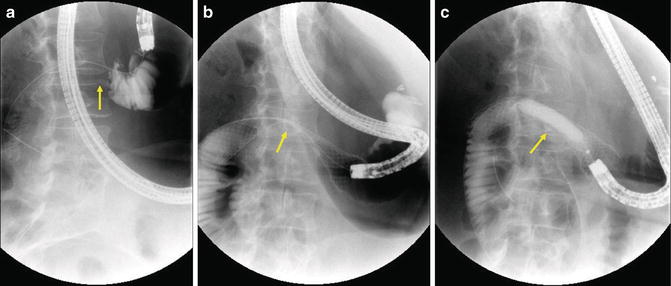

Fig. 12.3

(a–c) Multiple NSAID webs in duodenum and jejunum treated with (d–j) balloon dilation. Patient was taking ibuprofen for rheumatoid arthritis. Eight webs were dilated over two endoscopy sessions using both the single balloon and double balloon enteroscopes

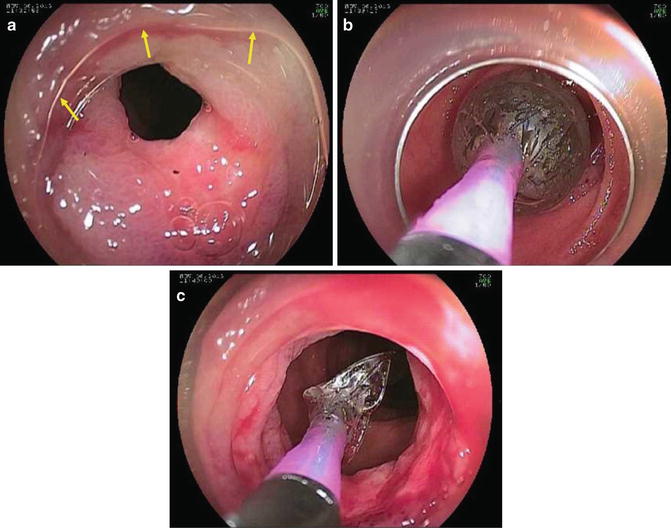

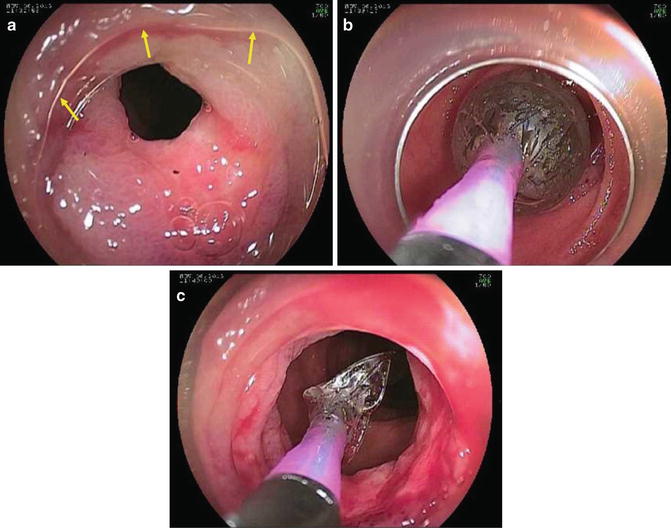

Fig. 12.4

(a–c) Additional endoscopy images using cap (arrows) on double balloon enteroscope to facilitate small-bowel web dilation (Images courtesy of Louis Wong Kee Song, Rochester, MN.)

Whether the endoscope is passed transorally or transrectally or via a stoma [1] depends on location of the stricture and any prior surgery. For example, most strictures in the duodenum will be within reach of an upper endoscope. On the other hand, reaching the second duodenum in patients with markedly distended stomachs from chronic obstruction may be difficult and a colonoscope may be useful. For passage of dilating balloons, the diameter of the working channel does not need to be large and thus standard upper endoscopes and pediatric colonoscopes as well as enteroscopes can be used. However, if one anticipates a large quantity of retained food then a large diameter may be more effective for suction. Accessories to remove food (e.g., Roth nets) should be readily available.

Moderate sedation or monitored anesthesia care (MAC) may be used, but airway protection with general anesthesia should be considered in patients with anticipated retained gastric contents and for prolonged procedures.

Fluoroscopy should be readily available and used for anticipated complex strictures in cases where the endoscope cannot be passed across the lesion and with angulated stenoses. Accessories for pancreaticobiliary endoscopy (catheters, stone extraction balloons, guidewires) and water-soluble contrast are helpful to traverse and define the anatomy of complex strictures.

Dilating balloons are available in a variety of sizes and lengths [2]. In addition, multisize balloons that inflate sequentially are also available as are balloons that accept a guidewire. Some balloons (CRE™, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA) come prepackaged with a “guidewire,” which is approximately 15 cm longer than the length of the balloon and can be adjusted and locked. Prior to the procedure, one should also be certain that the balloon catheter is long enough to pass through the chosen endoscope (colonoscope, enteroscope).

The endoscope is advanced to the site of the lesion. If the lesion can be easily traversed with the endoscope this should be attempted and obviates the need for a guidewire. If the endoscope cannot be passed, one should always consider use of fluoroscopy to be certain that the balloon is passing across the stricture. Additionally, the use of a guidewire allows passage of the balloon distal to the stricture and prevents impaction of the tip against the opposite bowel wall, which could result in perforation. Inflation of contrast in the balloon is helpful to be certain the balloon has crossed the entire stricture and whether the waist has effaced with dilation.

When long-length endoscopes are used for strictures in the jejunum it is helpful to use a clear cap attached to the tip, which can help negotiate tight corners and to assess the stricture at angulations [3]. Use of a lubricant (silicone or vegetable oil) within the endoscope channel also facilitates passage of the balloon within the working channel, which can be difficult when the endoscope is looped and/or when the tip is angulated.

The diameter of the balloon chosen is based upon disease process, prior therapy, and diameter of the stricture. For example, in patients with short, membranous strictures the risk of perforation is less and response is more likely than for a long-fibrotic stricture due to Crohn’s or radiation therapy. In the former, larger diameter balloons can be used more safely. In general, one should not dilate very tight, pinhole strictures to a diameter larger than 10–12 mm in one session. Additionally, slower dilation times and staged dilations are believed to be safer.

Outcomes Following Balloon Dilation

As previously mentioned, the response to balloon dilation is variable based upon the disease process, associated inflammation, and concomitant medical therapy. More than one dilation may be needed, and the optimal diameter to be reached and maintained as well as the interval between planned dilations are unknown.

There are many series on the outcomes following balloon dilation for Crohn’s disease strictures [4–11]. Short-term and long-term success (3 years) are approximately 80 % and 70 %, respectively [4].

Adverse events following endoscopic balloon dilation include sedation issues, perforation, and bleeding. Perforation is considered the most common, serious, and likely adverse event to result in need for surgery.

Miscellaneous Treatments

Injection of corticosteroids (Fig. 12.2d) or biologic agents (such as infliximab) into strictures during the same session as balloon dilation may improve long-term outcome of dilation, although this remains unproven. Indeed in one study the outcome was worse with steroid injection compared to placebo [12].

The use of a needle-knife to electroincise webs [13] and strictures [14, 15] has been used (Fig. 12.5); although it is likely best reserved for use by experienced endoscopists since it is performed freehand and may result in inadvertent perforation. Impacted small-bowel capsules can be removed, often concomitantly with web incision or balloon dilation of small-bowel strictures (Fig. 12.6).

Fig. 12.5

(a) Short-stricture/small-bowel web re-treated with (b, c) endoscopic electrosection (Images courtesy of Louis Wong Kee Song, Rochester, MN.)

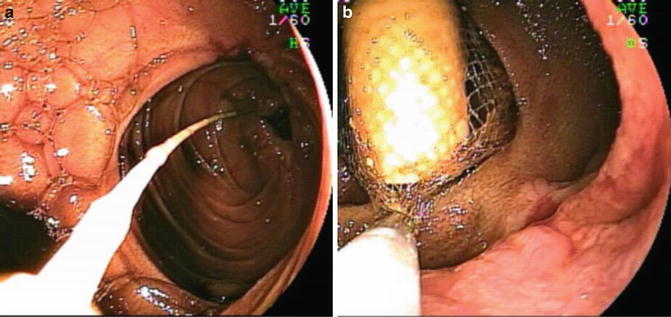

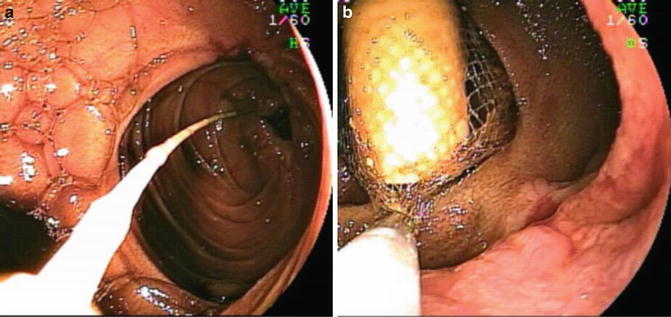

Fig. 12.6

(a) Distal jejunal anastomotic Crohn’s stricture with impacted small-bowel endoscopy capsule. (b) Following balloon dilation, the capsule was removed with a Roth net

Stent Placement

Most stents used for small bowel use are self-expandable metal stents (SEMS) (Fig. 12.7, Videos 12.1, 12.2, and 12.3). They are composed of a variety of metal alloys [16], although almost all are now composed of nitinol. SEMS are preloaded in a collapsed (constrained) position, mounted on a small-diameter delivery catheter. A central lumen within the delivery system allows for passage over a guidewire. Once the guidewire has been advanced beyond the site of pathology, the predeployed stent is passed over the guidewire and positioned across the stricture. The constraint system is released or withdrawn, which results in subsequent radial expansion of the stent and of the stenosed lumen (if present) during deployment. The radial expansile forces and degree of shortening differ between stent types [17]. SEMS may also have a covering membrane (covered or coated stents) to close fistulae and to prevent tumor ingrowth (and subsequent re-obstruction) through the mesh wall.

Fig. 12.7

Palliation of duodenal obstruction due to pancreatic cancer. (a) Injection of contrast through a biliary catheter outlines stricture in the duodenum (arrow). (b) Radiograph taken immediately after deployment of duodenal SEMS. Note proximal end is in the gastric antrum. Stent remains tightly contracted (arrow) and (c) is dilated with 10–12 mm CRE balloon (arrow)

The uncovered portion of SEMS becomes deeply imbedded into both the tumor and surrounding tissue [18, 19]. This prevents migration. Covering of the SEMS prevents imbedding and promotes stent migration; fully covered metal stents do not imbed and can be removed but are prone to migration [20]. In general, uncovered SEMS should not be used for treatment of benign strictures since they are usually not removable and can result in long-term problems such as tissue hyperplasia, obstruction, and ulceration.

Only three stents from two different manufacturers are available specifically for relief of enteral obstruction and all are uncovered (Table 12.2). These stents pass directly through the working channel of the endoscope (through-the-scope, TTS). Non-TTS stent placement (esophageal or colonic) into the duodenum with native anatomy is difficult, but possible. Additionally, one can also use smaller diameter (10 mm) TTS biliary stents alone or in side-by-side fashion (the latter allows a diameter of up to 20 mm to be achieved). A final option in the U.S. if a covered and removable stent is desired is the use of a covered TTS esophageal stent. Currently, the only such prosthesis available is the Niti-S (Taewoong Medical, Seoul, South Korea).

Table 12.2

Expandable duodenal stents

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree