Figure 3.1 Normal small bowel, endoscopic findings in the normal duodenum. A fine carpet of villi lines the duodenal lumen. The circular folds (plicae) of the small bowel have smooth borders.

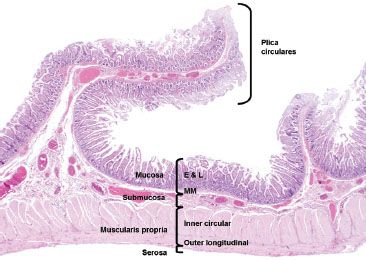

Figure 3.2 Normal small bowel, layers of the small intestine. This resection specimen illustrates the four main layers of the small bowel: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa. The mucosa consists of epithelium (E), lamina propria (L), and muscularis mucosae (MM). The submucosa sits between the muscularis mucosae and the muscularis propria (MP) and it consists of loose fibroconnective tissue and lymphovascular channels. The MP consists of two muscle layers: an inner circular and outer longitudinal. The outermost layer is the serosa. Note the plicae circulares are composed of a reduplication of mucosa held together by a submucosa core.

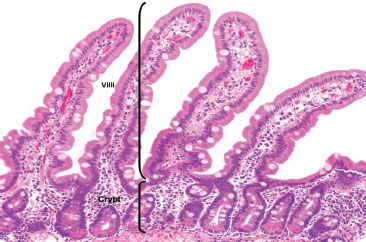

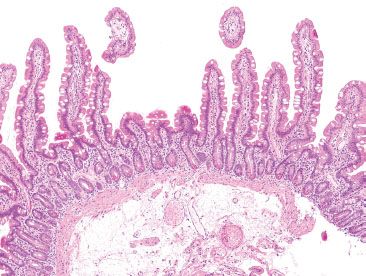

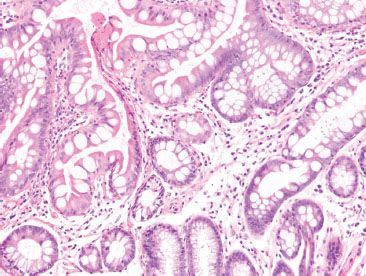

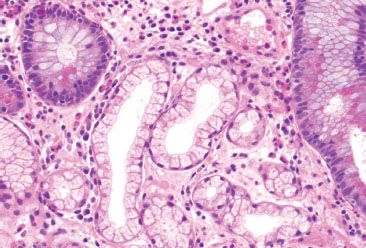

Figure 3.3 Normal small bowel. The crypt to villous ratio in the normal small bowel ranges from 1:3 to 1:5. The epithelial cells lining the villi are tall columnar absorptive cells and are intermittently punctuated by goblet cells. The base of the crypts contains visible bright pink Paneth cells with scattered endocrine cells (unperceivable at this magnification).

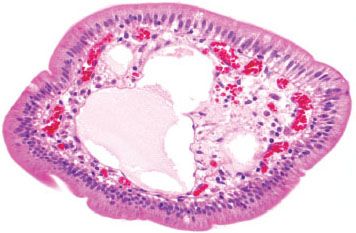

Figure 3.4 Normal small bowel, lacteals. The core of the villi are composed of lamina propria containing migratory chronic inflammatory cells, blood vessels, lymphatic channels, and smooth muscle cells. This example shows dilated lacteals in the tips of the villi, a finding that indicates lymphatic blockage of lymphatic flow of unclear significance.

Figure 3.5 Normal small bowel, cross section of villous projection. Higher magnification of a villous core highlights a dilated lymphatic space containing pale eosinophilic serum. Separate capillary vessels contain red blood cells, and scattered chronic inflammatory cells are present in the supporting substance.

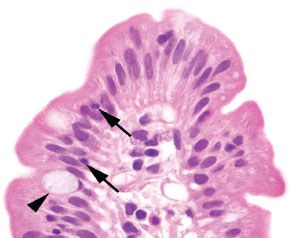

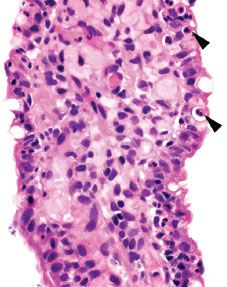

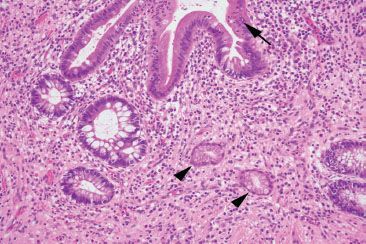

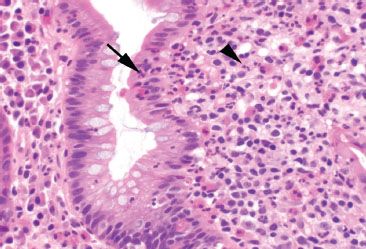

Figure 3.6 Normal small bowel, villous tip. The villous tip is lined by columnar cells with an absorptive brush border composed of microvilli. On H&E stain, this can be visualized as an eosinophilic “fuzzy” border. These absorptive columnar cells are punctuated by goblet cells (arrowhead), and small numbers of lymphocytes (arrows) may be seen traversing between them.

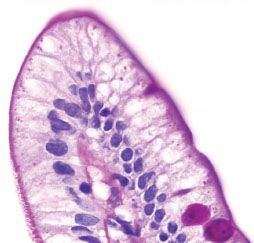

Figure 3.7 Normal small bowel, villous tips (PAS special stain). The microvillous brush border is crisp and deeply eosinophilic on a PAS special stain, which also highlights the goblet cells. Defective, broken, or smudgy brush borders should prompt consideration of microvillous inclusion disease, especially in infants. The cytoplasm of the columnar cells appears pale and homogeneous.

Figure 3.8 Normal small bowel, lipid “hang-up” (PAS special stain). This PAS stain of a villous tip reveals vacuolated cytoplasm of the absorptive columnar cells (compare to previous figure). This finding indicates lipid within the cytoplasm of the epithelial cells and is commonly seen among patients who have ingested food or drink prior to endoscopy. When severe, diffuse, or present in the pediatric population, it is worthwhile to consider a lipid transport disorder.

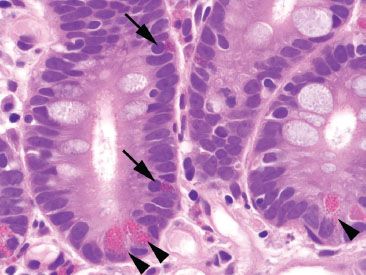

Figure 3.9 Normal small bowel, crypt base. Paneth cells (arrowheads) contain abundant brightly eosinophilic coarse granules that face the gland lumen. By comparison, enteroendocrine cells (arrows) have deeper red and smaller granules that face the basement membrane.

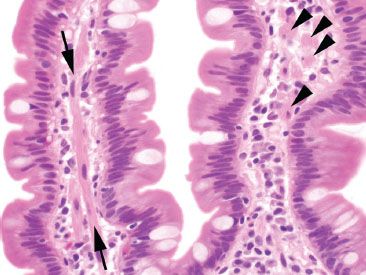

Figure 3.10 Normal small bowel, smooth muscle within villous core. Delicate tufts of smooth muscle (arrows) extend from the muscularis mucosae along the core of the villi. When cut in cross section (arrowheads), these can be mistaken for histiocytes, signet ring cell carcinoma, or infectious diseases (such as Mycobacterium avium intracellulare).

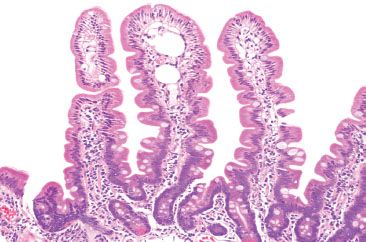

Figure 3.11 Normal small bowel, normal variant morphology in small intestine. Remember that the slide is a two-dimensional representation of three-dimensional tissues. Villi may be truncated if they extend out of the plane of section, as seen here. The adjoining long, slender villi reassure observers that there is not true villous atrophy.

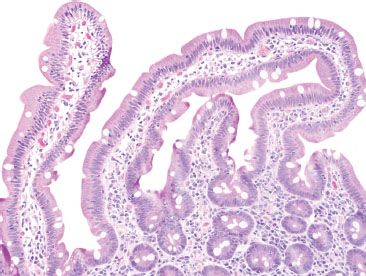

Figure 3.12 Normal small bowel, normal variant morphology in small intestine. Villi may vary from slender and fingerlike to broad and leaflike depending on geographic region or specific diets. Other variations, such as bridging villi (seen here) may also be seen in healthy patients.

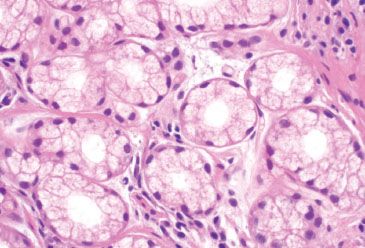

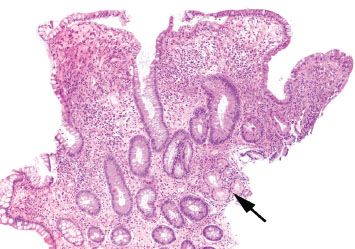

The submucosa of the duodenum contains ganglion cells of Meissner’s plexus, lymphatic and vascular structures, and is one of only two sites in the gastrointestinal tract that contains submucosal glands (the other being the esophagus). These Brunner glands are lobular collections of tubuloalveolar glands that are limited to the submucosa of the duodenum; however, up to one third of them can reside within the deep mucosa in the absence of pathology (Fig. 3.13).4 These glands are most concentrated at the gastro–duodenal junction and gradually decrease in number distally (Figs. 3.14 and 3.15). The glands are lined by cells (Fig. 3.16) that contain PAS positive and diastase-resistant neutral mucins, and scattered endocrine cells that secrete somatostatin, gastrin, and peptide YY. Secretions empty into the luminal crypt spaces by way of small ducts. Distally, the jejunum and ileum lack Brunner glands.

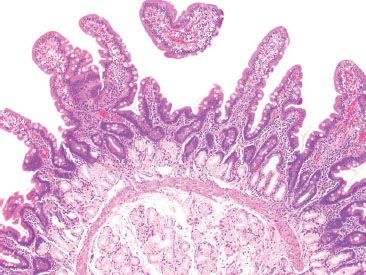

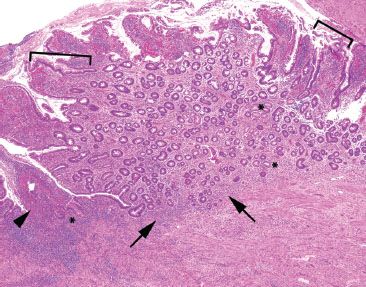

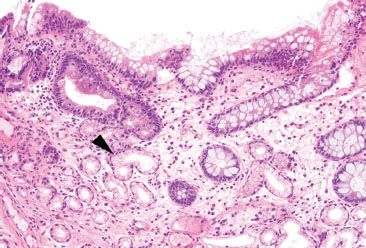

Figure 3.13 Normal small bowel, proximal duodenum with Brunner glands. Brunner glands are found exclusively in the proximal duodenum. Although their bulk lies in the submucosa, extension above the muscularis mucosae is not uncommon, even under normal conditions, as seen here.

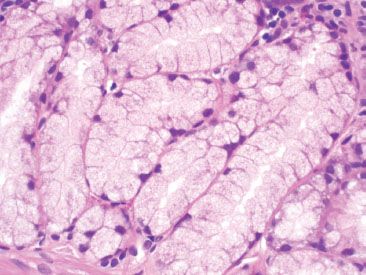

Figure 3.14 Normal small bowel, Brunner glands. Brunner glands are lined by cuboidal to columnar cells with pale, uniform cytoplasm and oval, basally located nuclei.

Figure 3.15 Normal small bowel, crushed Brunner glands. Crushed Brunner glands may sometimes take on a neural appearance, raising the differential diagnosis of a neural tumor.

Figure 3.16 Normal small bowel, Brunner glands (PAS special stain). Brunner glands contain PAS positive and diastase-resistant cytoplasmic mucin. This staining pattern can be helpful in differentiating crushed Brunner glands from a neural tumor.

The muscularis propria surrounds the submucosa and is composed of an inner circular and outer longitudinal layer of smooth muscle. Between these layers lies the myenteric plexus of Auerbach, a major neural plexus of the enteric nervous system. Externally, the bowel is enveloped by subserosal connective tissue and the mesothelial-derived serosa.

PEARLS & PITFALLS

Distinctive Differences Among Regions of Small Bowel

| Duodenum: | Contains submucosal Brunner glands, more abundant proximally Villi range from slender and fingerlike to broad and leaflike. |

| Jejunum: | Prominent, tall plicae circulares Villi are uniformly slender and fingerlike. |

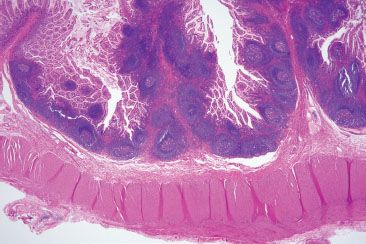

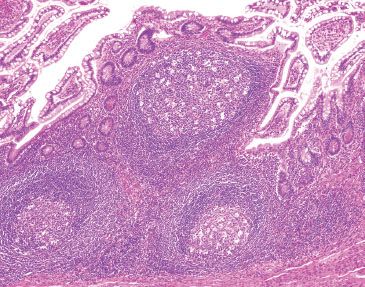

| Ileum: | Submucosal adipose tissue may be present, especially near the ileocecal valve Shorter and fewer plicae circulares Increased proportion of goblet cells Presence of Peyer patches (abundance of lymphoid aggregates) (Fig. 3.17) |

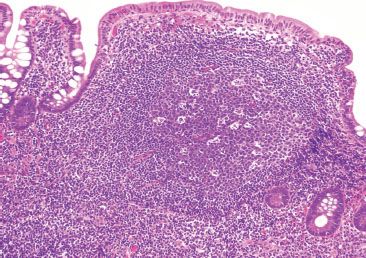

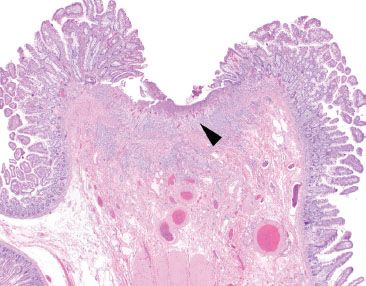

Figure 3.17 Normal small bowel, terminal ileum. Unencapsulated organized lymphoid nodules are found within the mucosa and submucosa of the terminal ileum. These Peyer patches are found exclusively in the ileum, which functions as an immunologic organ.

FAQ: My terminal ileum biopsy shows prominent lymphoid aggregates. How can I be sure I am not missing a sneaky hematolymphoid malignancy?

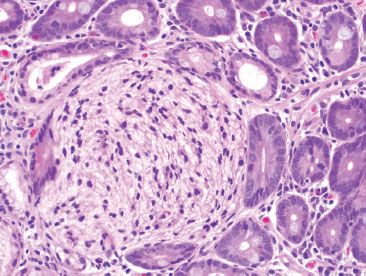

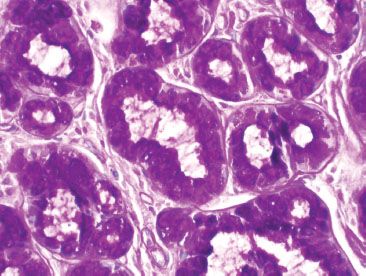

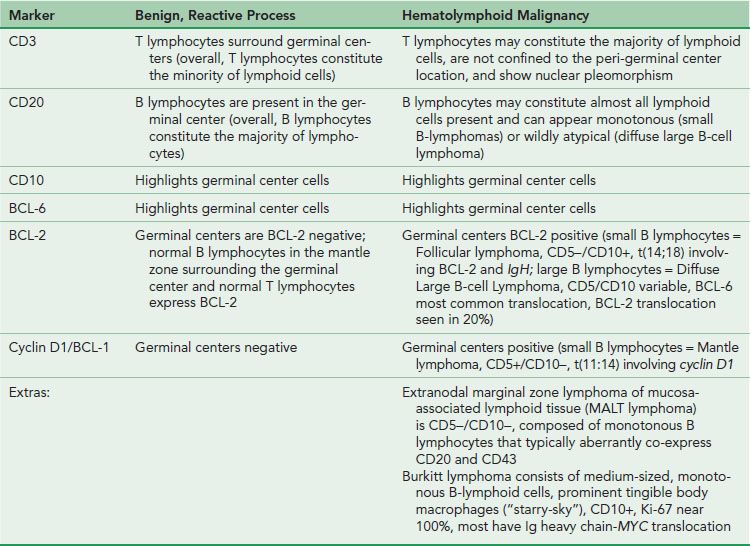

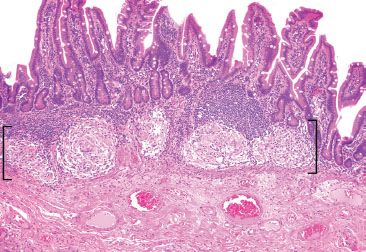

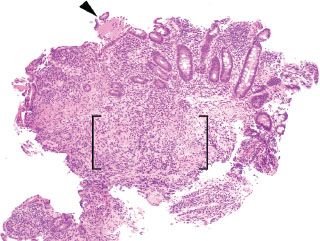

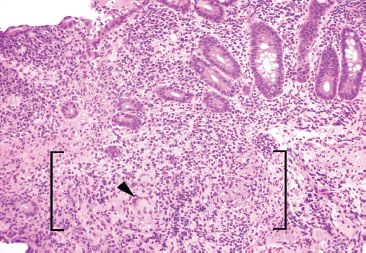

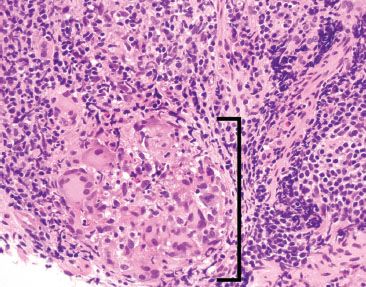

Answer: You are not alone! Prominent lymphoid aggregates can be especially alarming in the terminal ileum and, thus, are a common source of consultation. The small bowel serves as an essential component of the immune system through its perpetual surveillance of the passing luminal contents. Diligent immunosurveillance is facilitated through specialized epithelial cells (M-cells) that transport luminal antigens to the lymphoid aggregates (designated “Peyer patches” when seen in the terminal ileum). Hyperplastic lymphoid aggregates can be sufficiently large as to be visualized endoscopically and can also serve as intussusception lead points, especially in young children.5,6 The epicenter of lymphoid aggregates is in the mucosa but especially prominent cases can feature extension into the submucosa, raising concerns for a hematolymphoid malignancy. Histologic features reassuring for a benign, reactive process include the presence of germinal centers, tingible body macrophages, and a polymorphous constituent lymphoid population (i.e., a variety of cell sizes represented); however if the focus in question seems at all concerning, a quick immunohistochemical panel may be worthwhile (Figs. 3.19–3.37) (Table 3.1).

PEARLS & PITFALLS

CD43 also highlights plasma cells.

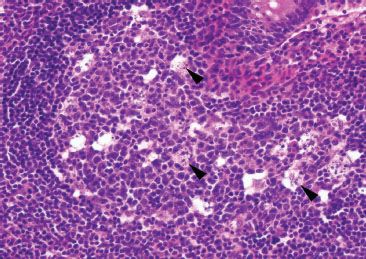

Lymphomas treated with Rituximab (anti-CD20) can be CD20 negative (use PAX5 to confirm B lymphocytes in these cases).

PEARLS & PITFALLS

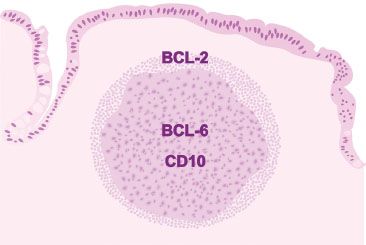

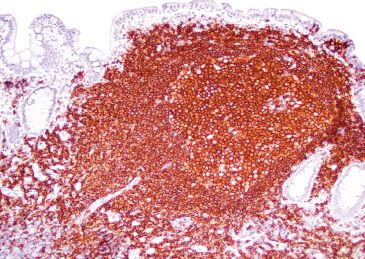

For those of us who do not routinely evaluate hematopathology specimens, it can be difficult to remember the significance of several of the similarly sounding hematopathology markers, particularly BCL-2, BCL-6, and CD10. If you relate to these challenges, consider this dartboard analogy as a handy learning tool (Figs. 3.18 and 3.19). In the game of darts, a player is awarded more points for landing a dart at the prized center bull’s eye due to the challenging nature of this difficult shot, and fewer points for landing a dart in the periphery of the dart board. In this analogy, imagine the center bull’s eye as a germinal center with the highest points awarded (BCL–6 and CD10). In contrast, the peripheral location outside of the germinal center is awarded fewer points (BCL–2). Importantly, this analogy only works for normal lymphoid aggregates! Follicular lymphoma, for example, is characterized by BCL-2 reactive germinal centers due to the t(14;18) rearrangement of BCL-2 and the immunoglobin heavy chain (IgH). See also Table 3.1.

TABLE 3.1: Quick and Dirty Immunohistochemical Panel for Prominent Lymphoid Aggregates versus Select Hematolymphoid Malignancies

Figure 3.18 Dart game analogy. If it is difficult to remember the significance of BCL-2, BCL-6, and CD10 as they relate to normal lymphoid aggregate architecture, consider this dartboard analogy. In the game of darts, a player is awarded more points for landing a dart at the center bull’s eye as compared to the periphery of the dartboard. In this analogy, imagine the bull’s eye as a germinal center with the highest points awarded (BCL-6 and CD10). In contrast, the peripheral location is outside of the germinal center and fewer points are awarded for these less challenging shots (BCL-2).

Figure 3.19 Normal lymphoid aggregate, illustration. In a normal lymphoid aggregate, the germinal center is highlighted by BCL-6 and CD10 (analogous to a dartboard’s prized bull’s eye) and is negative for BCL-2. Recall, normal B lymphocytes in the mantle zone surrounding the germinal center and normal T lymphocytes express BCL-2 (analogous to a dartboard’s periphery). Therefore, interpretation of BCL-2 always requires concomitant interpretation of CD20 B lymphocyte marker and CD3 T lymphocyte marker.

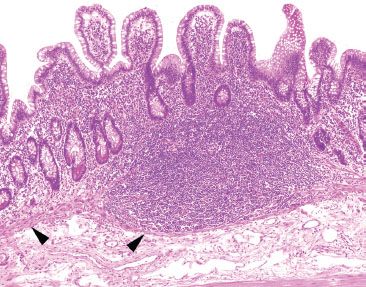

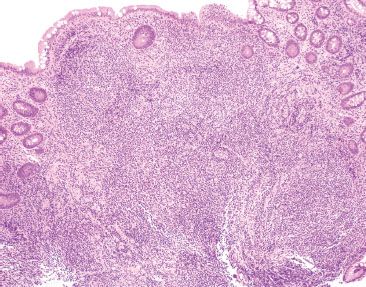

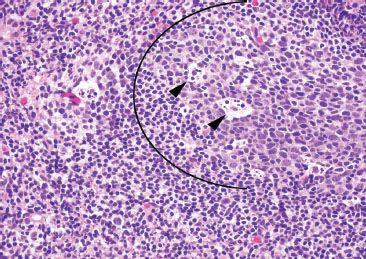

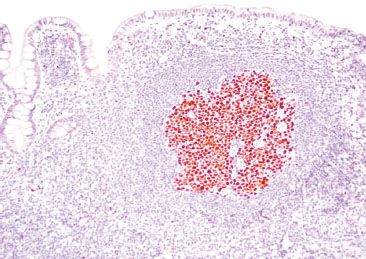

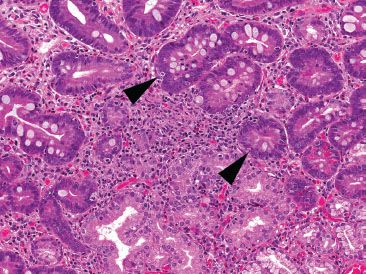

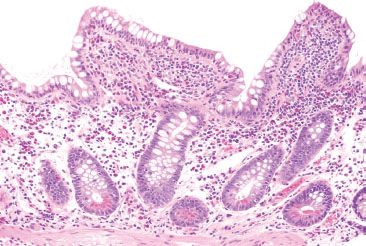

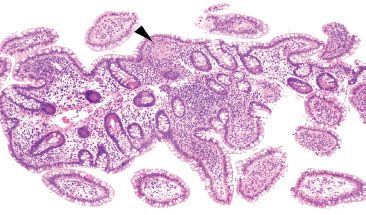

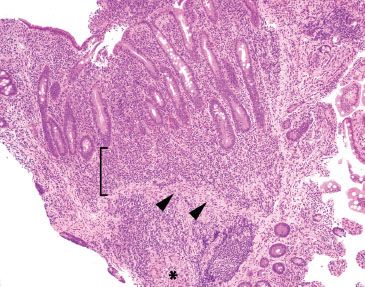

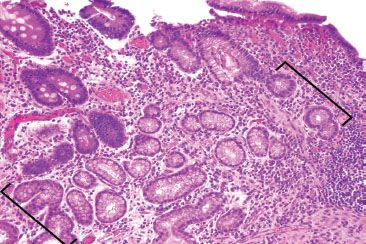

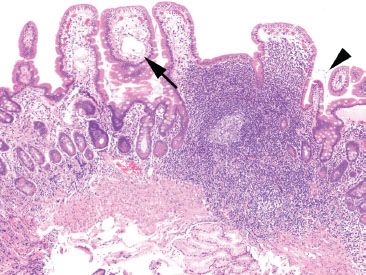

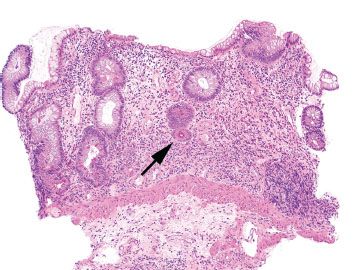

Figure 3.20 Normal terminal ileum. The overlying villi of the terminal ileum are characteristically shorter than those seen in the duodenum and jejunum (Figs. 3.3 and 3.13). At low power, the prominent lymphoid aggregate is seen confined within the mucosa (arrowheads highlight the narrow wisp of muscularis mucosae). Although the crypts are not identical copies of each other (the crypts are variably sized with varying amounts of intervening lamina propria), these slight differences are due to the prominent lymphoid aggregate and are entirely within the spectrum of normal terminal ileum histology. The lymphoid aggregate gently pushes the crypts apart; there is neither acute inflammation actively destroying the epithelium nor features of chronic injury (such as pyloric gland metaplasia). As a result, the superficial epithelium could be theoretically pulled off the lymphoid aggregate since there is no destructive inflammatory injury tethering the epithelium to the lymphoid aggregate. See figures 3.64, 3.66–3.70 to contrast this normal architecture with features of established active chronic injury.

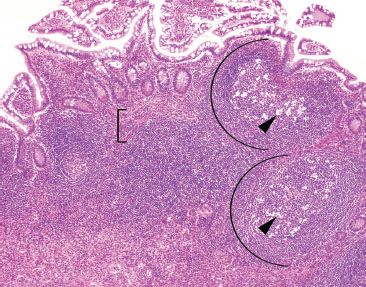

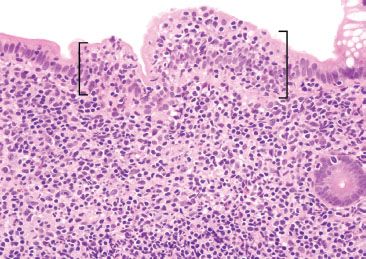

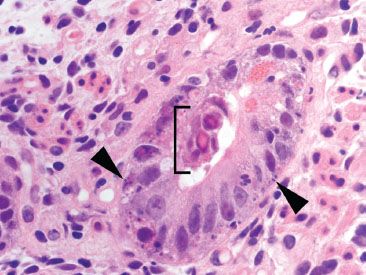

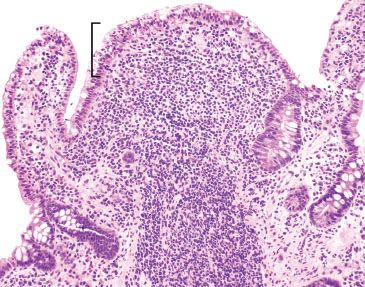

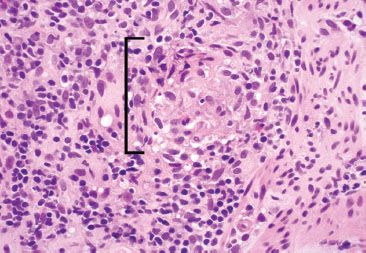

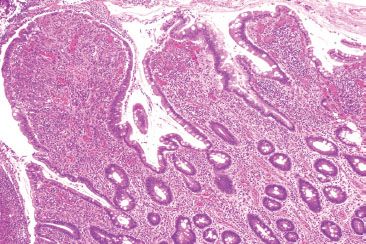

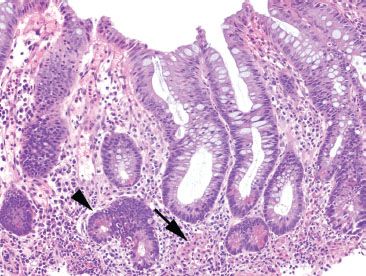

Figure 3.21 Normal terminal ileum. As this case illustrates, large lymphoid aggregates can occasionally extend below the muscularis mucosae (bracket) into the submucosa. Features in support of a benign process include variably sized lymphoid aggregates, germinal centers (arcs), tingible body macrophages (macrophages containing apoptotic debris in the cytoplasm, arrowheads), and a polymorphous lymphoid population (variably sized lymphocytes, best seen at high-power, Figures 3.29–3.30).

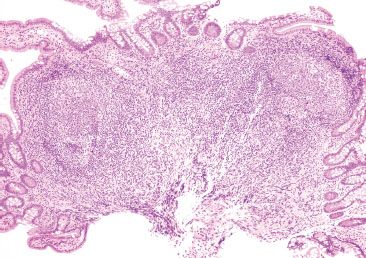

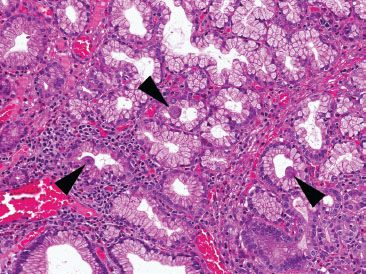

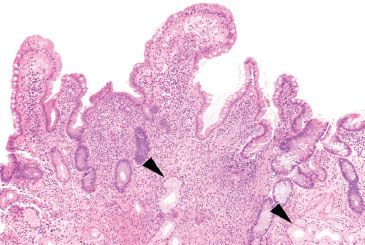

Figure 3.22 Normal terminal ileum. Note how the overlying epithelium could be theoretically “peeled” off the lymphoid aggregates since the large lymphoid aggregates are seen gently pushing aside the epithelium and not associated with active chronic inflammatory injury. Note the features of benignity: variably-sized lymphoid aggregates, germinal centers, and tingible body macrophages.

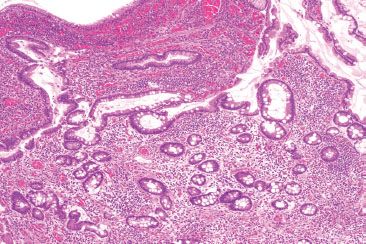

Figure 3.23 Normal terminal ileum. With such large prominent aggregates, the ever so slight scattered appearance to the crypts is entirely within the spectrum of normal terminal ileum architecture. Note that the overlying epithelium could be theoretically “peeled” off the lymphoid aggregates since there is no active chronic inflammatory injury linking the lymphoid aggregates to the epithelium.

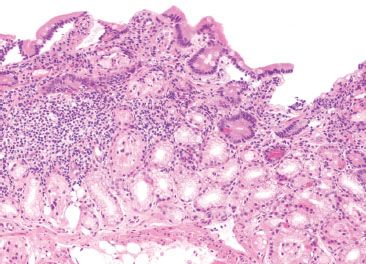

Figure 3.24 Normal terminal ileum with variably sized lymphoid aggregates, germinal centers, and tingible body macrophages.

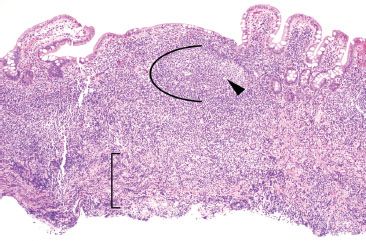

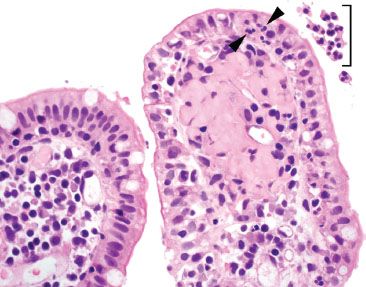

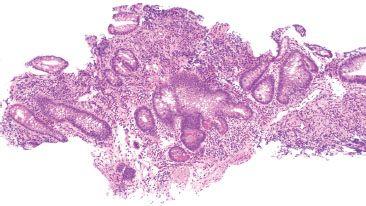

Figure 3.25 Normal terminal ileum. Crushed lymphoid tissue traversing the muscularis mucosae can raise concerns for a malignant hematolymphoid process (bracket). In this case, however, the intact lymphoid aggregate shows germinal centers (arc), tingible body macrophages (arrowheads), and a polymorphous lymphoid population, all features of a benign lymphoid process.

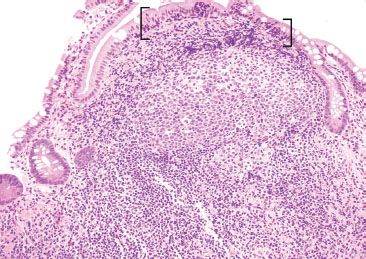

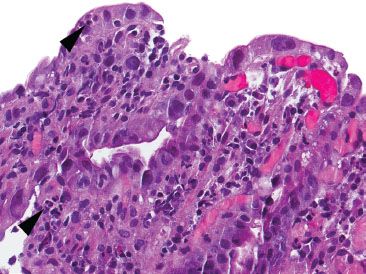

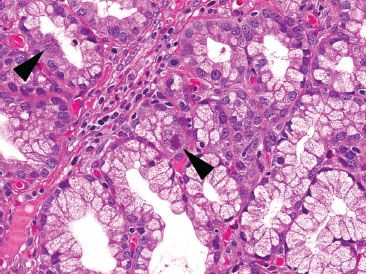

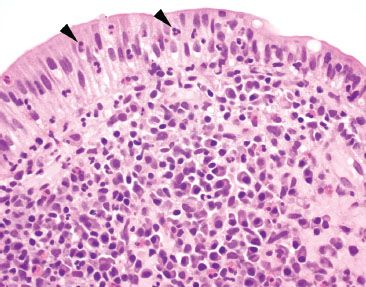

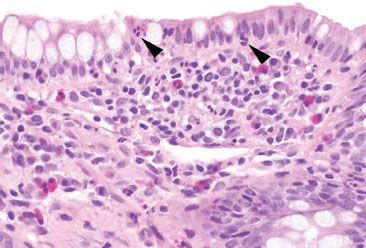

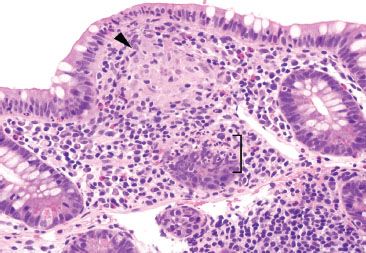

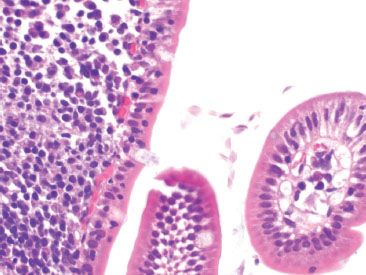

Figure 3.26 Normal terminal ileum. On higher power, a germinal center with tingible body macrophages is seen. Note that increased IELs are a normal finding in epithelium overlying lymphoid aggregates (brackets).

Figure 3.27 Normal terminal ileum. On higher power, the increased IELs are better appreciated (brackets). Recall, increased IELs are a normal finding in epithelium overlying lymphoid aggregates.

Figure 3.28 Normal terminal ileum. This high power view features a reactive germinal center with numerous tingible body macrophages (arrowheads). Tingible body macrophages harbor engulfed apoptotic debris, accounting for their characteristic cytoplasmic morphology.

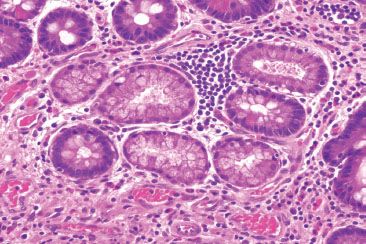

Figure 3.29 Normal terminal ileum. This focus illustrates important features of a benign lymphoid aggregate: a germinal center (arc), tingible body macrophages (arrowheads), and variably sized lymphocytes (small, medium, and large lymphocytes).

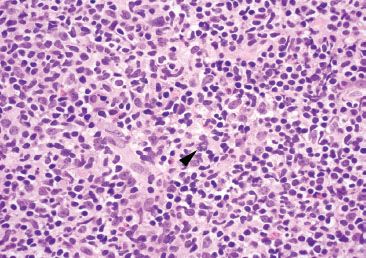

Figure 3.30 Normal terminal ileum. The polymorphous nature of this benign lymphoid aggregate is best seen at high power (note the various sized and shaped lymphocytes). A rare mitotic body is seen (arrowhead), a feature not unusual for reactive lymphoid aggregates.

Figure 3.31 Normal terminal ileum. Prominent lymphoid aggregates can be alarming and, consequently, are a common source of consultation. Most typically, recognition of the key H&E features of benignity is sufficient to render a diagnosis of an unremarkable lymphoid aggregate: as in this case, germinal centers, tingible body macrophages, and variably sized lymphocytes are seen. Sometimes, however, a quick immunostain panel approach can be reassuring.

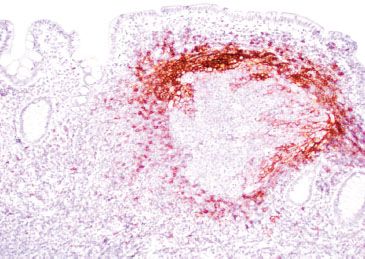

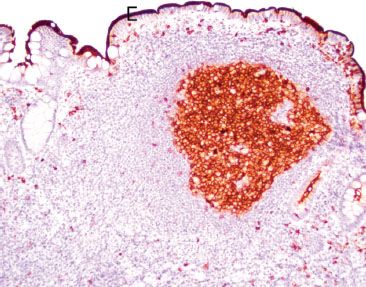

Figure 3.32 Normal terminal ileum (CD23 immunostain). A CD23 highlights the follicular dendritic cell meshwork surrounding the germinal centers, a feature of intact (normal) lymphoid aggregate architecture.

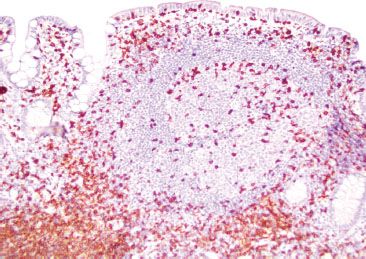

Figure 3.33 Normal terminal ileum (CD3 immunostain). A CD3 highlights T lymphocytes, which are predominantly seen surrounding the germinal center. On H&E, these lymphocytes were uniform and small, no atypical cytologic features were seen.

Figure 3.34 Normal terminal ileum (CD20 immunostain). A CD20 highlights B lymphocytes, which are the majority of the lymphoid constituents.

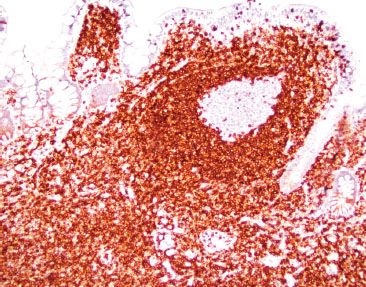

Figure 3.35 Normal terminal ileum (BCL-6 immunostain). Various artifacts occasionally make germinal centers difficult to discern. In such cases, BCL-6 and CD10 are equally helpful markers that highlight germinal centers.

Figure 3.36 Normal terminal ileum (CD10 immunostain). Like BCL-6, CD10 also highlights germinal centers. Of note, CD10 also highlights a crisp/intact brush border characteristic of normal small bowel mucosa (bracket). Defective, broken, or smudgy brush borders should prompt consideration of microvillous inclusion disease, especially in infants.

Figure 3.37 Normal terminal ileum (BCL-2 immunostain). Normal germinal centers are BCL-2 negative. If the germinal center is BCL-2 reactive, consider follicular lymphoma, which is characterized by the t(14;18) rearrangement of BCL-2 and the immunoglobin heavy chain (IgH). Importantly, recall that normal B lymphocytes in the mantle zone surrounding the germinal center and normal T lymphocytes express BCL-2. Therefore, interpretation of BCL-2 always requires concomitant interpretation of CD20 B lymphocyte marker, CD3 T lymphocyte marker, and a germinal center marker (BCL-6 or CD10).

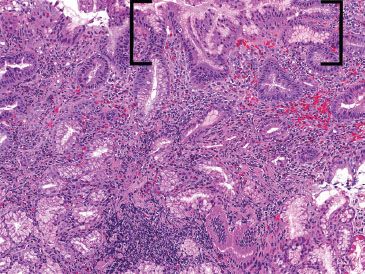

ACUTE DUODENITIS PATTERN

Figure 3.38 Acute duodenitis pattern. Acute duodenitis refers to acute inflammation in the duodenal epithelium (arrowheads). In this particular example, infiltrating pancreatic adenocarcinoma (not shown) was identified lurking within the acute inflammation, underscoring the importance of recognizing seemingly bland clues, such as acute duodenitis, to help uncover critical diagnoses.

CHECKLIST: Etiologic Considerations for the Acute Duodenitis Pattern (Fig. 3.38)

Peptic Injury (due to excess acid)

Peptic Injury (due to excess acid)

Reactive Duodenitis (mild histologic changes)

Reactive Duodenitis (mild histologic changes)

Peptic Ulcer Disease (marked histologic changes)

Peptic Ulcer Disease (marked histologic changes)

Infection

Infection

Medication (NSAIDs)

Medication (NSAIDs)

Cigarette Smoking

Cigarette Smoking

Zollinger–Ellison Syndrome

Zollinger–Ellison Syndrome

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Infiltrative Processes

Infiltrative Processes

Radiation Injury

Radiation Injury

Ischemia

Ischemia

Vasculitis

Vasculitis

The acute duodenitis pattern refers to acute inflammation in the epithelium of the duodenum. This injury pattern is most commonly seen in the setting of peptic injury, infection, and medication injury, but can also be a clue to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), infiltrative processes, ischemia, radiation injury, and others. Careful attention to the clinical presentation and scrutiny of the surrounding mucosa is critical to arriving at the correct diagnosis. Acute duodenitis can be further classified as “mild,” “moderate,” or “marked” based on the qualitative distribution of the acute inflammation; counting neutrophils is not necessary. For a simple rule of thumb, “mild” includes villitis and cryptitis, “moderate” is indicated by crypt abscesses, and “marked” is indicated by sheets of neutrophils with or without erosion/ulceration. By definition, histologic features of chronic injury are absent, that is, architectural distortion, gastric foveolar metaplasia, and pyloric gland metaplasia are not seen with simple acute duodenitis. When features of chronic damage are established, the injury has occurred over a longer time period and the differential diagnostic considerations expand to include chronic injury of any sort (i.e., chronic peptic injury, chronic infections, chronic medication injury, in addition to IBD and others).

PEPTIC INJURY

Peptic injury describes a broad morphologic range of duodenal injury ranging from spotty acute inflammation to deep, penetrating ulcers. At the mild end of the spectrum, peptic injury manifests with the following histologic features:

1. Increased plasma cell infiltration

2. Neutrophils in the lamina propria or epithelium (or in both) (Figs. 3.39 and 3.40)

3. Reactive epithelial changes including villous blunting

4. Gastric foveolar (mucin cell) metaplasia

This mild injury pattern is interchangeably referred to as “reactive duodenopathy,” “gastric foveolar metaplasia,” “chronic peptic duodenopathy,” “chronic peptic duodenitis” and “peptic-type duodenopathy.” Based on the variable villous blunting, the pattern is more extensively discussed in the Malabsorption Pattern, this chapter. Briefly, this pattern is historically associated with excessive gastric acid production coupled with insufficient protective effects of bicarbonate. Strong links with Helicobacter are not seen in reactive duodenopathy, in contrast to peptic ulcer disease (PUD). PUD represents the extreme range of peptic injury characterized by ulcerations, marked acute and chronic inflammation, mucin attenuation, and reactive changes. PUD is attributable to Helicobacter in the majority of cases, although nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and cigarette smoking are also implicated. Recurrent, multifocal, or marked peptic ulcer disease may serve as an important red flag to Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. Recall that Zollinger–Ellison syndrome is characterized by gastrinoma (and tumor-mediated hypergastrinemia), hyperplasia of the oxyntic compartment, increased gastric acid production, and gastric and small bowel ulcerations. See also Hyperplasia Pattern, Stomach Chapter.

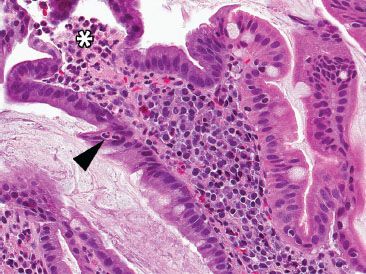

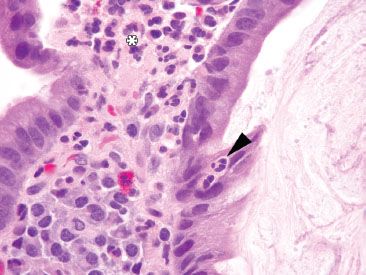

Figure 3.39 Acute duodenitis pattern, peptic injury. Acute duodenitis is an etiologically nonspecific injury pattern most commonly seen in the setting of peptic injury, infection, and medication injury. Neutrophils are seen in the epithelium (arrowhead) and lamina propria (asterisk).

Figure 3.40 Acute duodenitis pattern, peptic injury. Under oil immersion, the neutrophils are more easily seen in the epithelium (arrowhead) and lamina propria (asterisk). The cause of the injury is unknown.

INFECTION

Figure 3.41 Acute duodenitis pattern, Helicobacter pylori. This case of Helicobacter pylori duodenitis shows similar features to Helicobacter pylori gastritis. At low power, increased acute and chronic inflammation is seen, which is particularly prominent toward the superficial mucosa. Gastric foveolar metaplasia (bracket) provides a hospitable environment for Helicobacter and should always be carefully checked for organisms.

Figure 3.42 Acute duodenitis pattern, Helicobacter pylori. At higher power, intraepithelial acute inflammation (arrowheads) and prominent superficial plasma cells provide helpful red flags to the underlying Helicobacter infection. A rare Helicobacter organism is seen (arrow). Since this case had no corresponding stomach biopsy, the only opportunity to diagnosis and treat the infection stemmed from recognizing this injury pattern and carefully searching for the rare Helicobacter organisms.

Figure 3.43 Acute duodenitis pattern, Helicobacter pylori. This low power image shows features highly suspicious for a Helicobacter infection with a prominent superficial lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, acute inflammation (not seen at this power), and gastric metaplasia (brackets). The organisms were seen in abundance on a Diff–Quik special stain (not shown) in the gastric metaplastic zones.

Figure 3.44 Acute duodenitis pattern, Helicobacter pylori. This low power image shows features reminiscent of those of exuberant Helicobacter gastritis. Note the prominent superficial lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and gastric metaplasia (brackets). Brisk acute inflammation and Helicobacter organisms were seen on higher power (not shown).

Figure 3.45 Acute duodenitis pattern, gastric foveolar metaplasia (PAS/AB). A PAS/Alcian blue pH 2.5 special stain highlights the neutral mucin characteristic of gastric foveolar metaplasia (bracket), similar to native stomach mucosa. In contrast, goblet cells display basophilia because of acidic mucin (arrowhead).

Figure 3.46 Acute duodenitis pattern, gastric foveolar metaplasia (PAS/AB). Gastric foveolar metaplasia appears eosinophilic because of neutral mucin (bracket); goblet cells are basophilic because of acidic mucin (arrowhead). Note the abundant superficial plasma cells with a sprinkling of acute inflammation, features suggestive of Helicobacter duodenitis (organisms not shown).

Figure 3.47 Acute duodenitis pattern, adenovirus infection. Prominent apoptotic bodies (arrowheads) and scattered intraepithelial neutrophils serve as helpful red flags to the characteristic adenovirus inclusions (bracket). Note the glassy and eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions typical for adenovirus. Since similar findings can be seen with degenerative change, a confirmatory adenovirus immunostain was performed and was reactive (not shown).

Figure 3.48 Acute duodenitis pattern, CMV infection. In this case, a smattering of acute inflammation and increased apoptotic bodies (arrowheads) serve as important clues to the diagnosis of CMV enteritis.

Figure 3.49 Acute duodenitis pattern, CMV infection. Careful inspection of the nearby mucosa revealed abundant Brunner epithelium with classic CMV viral cytopathic effect (arrowheads): cytolomegaly, prominent nucleoli, and both nuclear and cytoplasmic viral inclusions are seen. In the stomach and small bowel, viral cytopathic effect is often more conspicuous in the epithelium than the stromal and endothelial cells. These viral inclusions were diagnostic (a CMV immunostain was not required).

Figure 3.50 Acute duodenitis pattern, CMV infection. Higher power of another field shows classic CMV viral cytopathic effect with cytolomegaly and prominent nuclear and cytoplasmic viral inclusions (arrowheads). Although not included on the requisition, chart review revealed a history of febrile diarrhea, metastatic colorectal carcinoma, and concurrent chemotherapy. This case underscores the importance of recognizing this acute enteritis pattern, even when the history of immunosuppression is not apparent on the requisition.

Helicobacter remains a leading contender in infectious agents associated with the acute duodenitis pattern. Its histology can show similar features to the analogous gastric process with brisk acute and chronic inflammation and conspicuous superficial plasma cells (Figs. 3.41–3.46). If not apparent on H&E, a Helicobacter immunostain can be utilized for suspicious cases.7 Not to be missed, adenovirus and CMV are similarly important infectious agents, particularly in immunocompromised patients. The characteristic intranuclear adenovirus inclusions are glassy eosinophilic, and can be highlighted with an adenovirus immunostain (Fig. 3.47). Adenovirus treatment involves lowering immunosuppressive agents, making the distinction from graft versus host disease (GVHD) critical because GVHD therapy requires increased immunosuppressive therapy. See also GVHD, Lymphocytic Pattern, Esophagus Chapter. Similar to CMV infections of other sites, the characteristic inflammatory backdrop shows a prominence of mononuclear inflammation (lymphocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells), in addition to active background injury and increased apoptotic bodies. The classic CMV viral cytopathic effect includes nuclear enlargement, prominent nuclear inclusions (with an “owl’s eye” appearance), and cytoplasmic inclusions (Figs. 3.48–3.50). In the stomach and small bowel, CMV viral cytopathic changes can be more prominent in the epithelium rather than the stromal and endothelial cells; the latter changes more common in CMV esophagitis, colitis, and proctitis.

KEY FEATURES of the Acute Duodenitis Pattern:

• Acute duodenitis refers to acute inflammation in the epithelium of the duodenum.

• The most common etiologies include peptic injury, infection, and medication injury.

• Reactive duodenopathy shows mild mucosal damage and is due to excess gastric acid; it has no strong association with Helicobacter.

• Peptic ulcer disease is due to Helicobacter in the majority of cases, although NSAIDs and cigarette smoking also play a causal role.

• Helicobacter remains the most common identifiable infectious etiology of the acute duodenitis pattern.

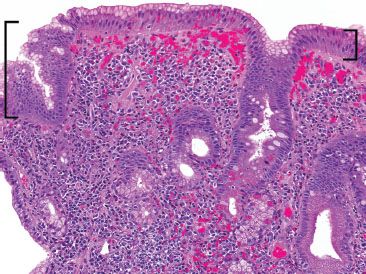

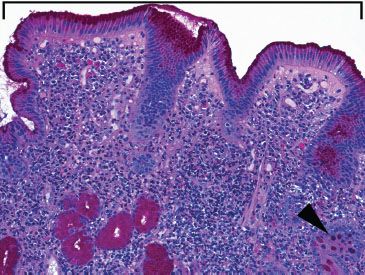

ACUTE ILEITIS PATTERN

Figure 3.51 Acute ileitis pattern. Acute ileitis refers to acute inflammation in the epithelium of the ileum (arrowheads). It is most commonly caused by medication, infection, and inflammatory bowel disease.

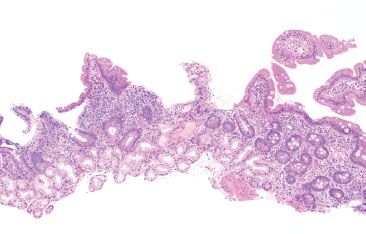

Similar to that in the acute duodenitis pattern, acute inflammation in the epithelium of the ileum can qualitatively be scored “mild,” “moderate,” or “marked” based on the relative prominence of acute inflammation in the epithelium (Figs. 3.51–3.55). Comparatively, the acute ileitis pattern is associated with a slightly modified differential diagnostic list of etiologic considerations. In this section, the discussion emphasizes etiologic considerations particularly important to the ileum.

Figure 3.52 Acute ileitis pattern, aphthoid lesion. The diagnosis of acute ileitis implies the absence of chronic injury, as seen in this figure). Although the lymphoid aggregate is gently pushing apart the crypts, there is no chronic injury of the epithelium (note the epithelium could be theoretically peeled off the lymphoid aggregate since the epithelium is not tethered to the lymphoid aggregate by destructive inflammatory injury).

Figure 3.53 Acute ileitis pattern, aphthoid lesion. Higher power of previous case. An aphthoid lesion/ulcer refers to acute inflammation in the epithelium overlying a lymphoid aggregate. In the appropriate clinicopathologic context, an aphthoid lesion can lend support to the diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Figure 3.54 Acute ileitis pattern. A pocket of luminal neutrophils is seen (bracket) along with acute inflammation in the epithelium (arrowheads).

Figure 3.55 Acute ileitis pattern, prominent ulceration. Acute ileitis refers to a fairly wide range of mucosal injury patterns ranging from scattered neutrophils in the epithelium to deep penetrating ulcerations and fissures. In this example, a prominent ulceration is featured (arrowhead), while the background mucosa is essentially unremarkable at this power. The terminal ileum findings were attributed to the established history of excessive NSAID usage.

CHECKLIST: Etiologic Considerations for the Acute Ileitis Pattern

Medications (i.e., NSAIDs, ipilimumab, other chemotherapeutic agents)

Medications (i.e., NSAIDs, ipilimumab, other chemotherapeutic agents)

Infection (CMV, Adenovirus, and Typical Stool Pathogens, including Yersinia, Salmonella, others)

Infection (CMV, Adenovirus, and Typical Stool Pathogens, including Yersinia, Salmonella, others)

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Infiltrative Processes (i.e., Amyloidosis or Malignancy)

Infiltrative Processes (i.e., Amyloidosis or Malignancy)

Radiation Injury

Radiation Injury

Ischemia

Ischemia

Vasculitis

Vasculitis

MEDICATIONS

Medication-related injury constitutes the most common cause of the acute ileitis pattern of injury, particularly in adults. In an endoscopic study of long-term NSAID users, up to 71% showed distal small bowel mucosal injury compared to only 10% of non-NSAID users (p < 0.001).8 NSAIDs mediate injury via nonselective inhibition of cyclooxygenase isoenzymes resulting in decreased production of mucosal protectant products, such as prostaglandins, mucin, and bicarbonate, and dampened microcirculation. The injury pattern can range from mild acute ileitis to erosions, deep-penetrating ulcerations, perforations, and necrosis (Fig. 3.55). The so-called diaphragm disease is a rare but clinically significant consequence seen in up to 2% of patients with chronic NSAID usage and is presumed to be pathognomonic for NSAID-related injury. See also Diaphragm Disease, Chronic Ileitis, this chapter. Although NSAID-related injury can occur at any point along the tubular GI tract, the terminal ileum is particularly vulnerable because of the increased popularity of extended release formulations that delay release of NSAIDs (and the associated mucosal damage) from the stomach to distal bowel segments, including the terminal ileum9 and even the colon.10,11 Other proposed factors include the geographic specific constraints of the terminal ileum; the prominent lymphoid aggregates and narrowed ileocecal valve may result in increased tablet-mucosal contact and related physical and or chemical injury.9

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

The acute ileitis pattern can also herald inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Although IBD is discussed at length in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Chronic Colitis, Colon Chapter, a few comments pertaining to the terminal ileum are warranted. Importantly, terminal ileal injury is not restricted to Crohn disease. Up to 17% of ulcerative colitis cases are associated with acute ileitis via a process termed “backwash ileitis.”12 “Backwash ileitis” occurs in a background of marked pancolitis whereby the inflammatory rich luminal contents in the colon are refluxed into the contiguous terminal ileum segment, causing associated inflammatory and reactive changes. The degree of terminal ileum injury is usually mild, or no greater than that in the cecum, and features of chronic mucosal injury are uncommon (Figs. 3.56 and 3.57).12 If terminal ileum restricted injury is present and the adjoining colon shows unremarkable mucosa, medication injury, infection, or Crohn disease would figure a more likely etiology.

When assessing the acute ileitis pattern, it is worthwhile to carefully scrutinize the background mucosa for any additional diagnostic clues that might help refine the diagnosis. For example, aphthoid lesions/ulcers consist of acute inflammation in the epithelium overlying lymphoid aggregates and their presence can lend support to a clinicopathologic diagnosis of Crohn disease (Figs. 3.52–3.54). Although granulomata can be difficult to detect in the normally busy-appearing terminal ileum biopsies, their presence can also be helpful when considering the possibility of Crohn disease, infection, sarcoidosis, or medication injury (Figs. 3.58–3.65). Features of chronic mucosal injury are also important to identify, such as pyloric gland metaplasia and architectural distortion, although these features can be seen with chronic injury of any sort, such as chronic NSAID-associated injury or chronic infections (Figs. 3.58–3.73). Histologic features of chronic mucosal injury are extensively discussed in Chronic Colitis, Colon Chapter. Based on the overlapping features between IBD, chronic medication injury, and chronic infection, IBD is remains a clinicopathologic diagnosis that must encompass all available clinicopathologic features (clinical symptomatology, disease course, disease distribution pattern, pertinent microbiologic studies, and family history, etc.).13

KEY FEATURES of the Acute Ileitis Pattern:

• Medication-related injury constitutes the most common etiology, followed by infection and IBD (Crohn disease > ulcerative colitis).

• This injury pattern ranges from mild acute ileitis to erosions, deep-penetrating ulcerations, perforations, and necrosis.

• Diaphragm disease is a rare consequence of chronic NSAID usage and refers to mucosal strictures that concentrically involve the bowel wall, narrowing the lumen to a pinhole size, resulting in obstruction.

• Assess the background mucosa for clues such as aphthoid lesions, granulomata, features of chronic mucosal injury, radiation injury, amyloidosis, and neoplasia, in attempts to uncover the etiology.

Figure 3.56 Acute ileitis pattern, backwash ileitis, ulcerative colitis. This ileal biopsy was taken from a patient with well-established ulcerative colitis.

Figure 3.57 Acute ileitis pattern, backwash ileitis, ulcerative colitis. Higher magnification of the previous figure reveals mild focal acute inflammation (arrowheads) that should not be mistaken for Crohn disease.

Figure 3.58 Granulomatous pattern (brackets), terminal ileum, sarcoidosis. This terminal ileum resection originated from a 58-year-old woman with an extensive history of sarcoidosis who presented with a small bowel obstruction. The background mucosa was unremarkable. AFB and GMS special stains were negative.

Figure 3.59 Acute ileitis pattern, granuloma, Crohn disease. This sneaky granuloma is almost miss-able on low power (arrowhead). This biopsy originated from a patient with a history of Crohn disease and scattered mucosal granulomata were seen throughout representative upper and lower gastrointestinal tract biopsies.

Figure 3.60 Acute ileitis pattern, granuloma, Crohn disease. On higher power, the granuloma is more easily spotted (arrowhead) as is the focal acute inflammation in the adjoining epithelium (bracket). AFB and GMS special stains were negative.

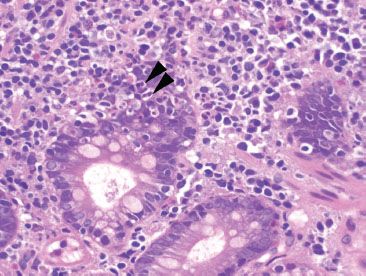

Figure 3.61 Acute ileitis pattern, erosive active chronic granulomatous ileitis, Crohn disease. Active chronic inflammation refers to acute injury (i.e., acute inflammation in the epithelium or crypt lumens, erosions, and or ulcerations) and chronic injury. In this case, an erosion is seen (arrowhead) along with an expansion of the lamina propria by a lymphohistiocytic inflammation (brackets).

Figure 3.62 Acute ileitis pattern, erosive active chronic granulomatous ileitis, Crohn disease. On intermediate power, a foreign body giant cell is more easily seen (arrowhead) in addition to vague granulomatous inflammation (brackets). Granulomata in Crohn disease are often poorly formed, as in this case.

Figure 3.63 Acute ileitis pattern, erosive active chronic granulomatous ileitis, Crohn disease. On highest power, the epithelioid morphology characteristic of granulomatous inflammation is seen (bracket). AFB and GMS special stains were negative.

Figure 3.64 Acute ileitis pattern, active chronic granulomatous ileitis, Crohn disease. At low power, crypt shortfall with basal lymphoplasmacytosis is seen: note that the crypts fall short of the muscularis mucosae (arrowheads) because of a basal layer of lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (bracket). Granulomata in Crohn disease (asterisk) can be notoriously difficult to appreciate in intensely inflamed specimens, as in this case. In contrast to normal terminal ileum architecture, note that it would be impossible to strip off the overlying epithelium in this case since the epithelium is inseparably melded to the associated active chronic inflammatory injury. Contrast this image with normal architecture (Figs. 3.20–3.25).

Figure 3.65 Acute ileitis pattern, active chronic granulomatous ileitis, Crohn disease. On higher power a granuloma with foreign body giant cells is more easily appreciated (bracket). AFB and GMS special stains were negative.

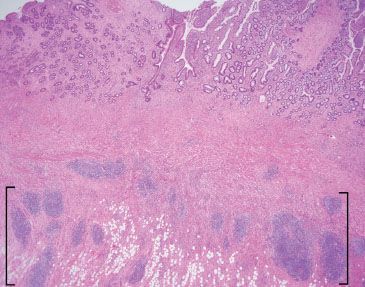

Figure 3.66 Acute ileitis pattern, active chronic ileitis, Crohn disease. Active chronic injury implies both acute and chronic inflammatory injury. Although acute inflammation is not apparent at this magnification, features of established chronic injury (chronicity) include pyloric gland metaplasia (best appreciated at higher power) and architectural distortion (note the variably sized crypts with variable intervening lamina propria). Also note the transmural fibrosis and chronic inflammation, and subserosal lymphoid aggregates (brackets), features compatible with the history of established Crohn disease.

Figure 3.67 Acute ileitis pattern, ulcerative active chronic ileitis, Crohn disease. This resection is from a patient with a history of terminal ileum-restricted Crohn disease. The image features both acute injury (ulceration (arrowhead) and acute inflammation in the epithelium (not shown)) and chronic injury (gastric foveolar metaplasia [brackets], pyloric gland metaplasia [asterisks], and slight architectural distortion with variably sized crypts, variable intervening lamina propria, minimal crypt shortfall, and basal lymphoplasmacytosis [arrows]).

Figure 3.68 Acute ileitis pattern, ulcerative active chronic ileitis, Crohn disease. Alternate field. Luminal ulcer debris is seen along with features of chronic mucosal injury (gastric foveolar metaplasia and architectural distortion).

Figure 3.69 Acute ileitis pattern, active chronic ileitis, Crohn disease. Alternate field. Architectural distortion is often best seen at low power: note the variably sized crypts with variable intervening lamina propria.

Figure 3.70 Acute ileitis pattern, active chronic ileitis, Crohn disease. Architectural distortion can also be appreciated on small bits of biopsy material, as this case. Note the central bizarrely shaped crypt with greater than seven branches, and the variable amount of intervening lamina propria throughout, both features of chronic mucosal injury. Acute ileitis was also seen (not shown).

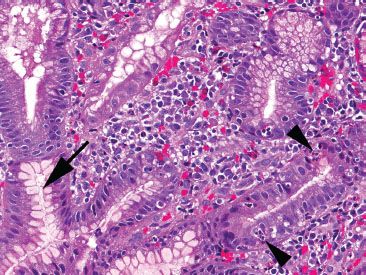

Figure 3.71 Acute ileitis pattern, active (arrow) chronic (arrowheads) ileitis, Crohn disease.

Figure 3.72 Acute ileitis pattern, active chronic ileitis, Crohn disease. Pyloric gland metaplasia is evidence of chronic mucosal injury (brackets). Pyloric gland metaplasia of the ileum is histologically identical to the pyloric-type glands of the gastric cardia and antrum and to Brunner glands of the duodenum. These glands are composed of mucus secreting cells with abundant clear foamy cytoplasm and basally located nuclei. A PAS/AB special stain would highlight eosinophilic neutral mucin (not shown).

Figure 3.73 Acute ileitis pattern, active chronic ileitis, Crohn disease. Higher power of previous case.

CHRONIC INFLAMMATION PATTERN

Figure 3.74 Chronic inflammation, nonspecific. Not uncommonly, small bowel biopsies show a chronic inflammatory infiltrate without other specific features. Following systematic review of all tissue compartments for clues, and chart review for clinical correlates, some cases just remain “nonspecific.”

CHECKLIST: Etiologic Considerations for the Chronic Inflammation Pattern

Reactive Duodenopathy

Reactive Duodenopathy

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Infection

Infection

Inflammatory or Immune-Regulated Disorders (i.e., Psoriasis)

Inflammatory or Immune-Regulated Disorders (i.e., Psoriasis)

The chronic inflammation pattern is defined by mild expansion of the lamina propria with mononuclear cells or lymphoid aggregates in the absence of villous blunting or intraepithelial lymphocytosis (Fig. 3.74). This is the most nonspecific of the small bowel patterns, but also among the most common. Etiologic considerations include reactive duodenopathy (see Malabsorption Pattern, this chapter), infection, and upper tract involvement by IBD (Figs. 3.75 and 3.76). Up to 40% of patients with Crohn disease may show active, chronic, and granulomatous inflammation in varying proportions.14 By comparison, ulcerative colitis is typically limited to the lower gastrointestinal tract, although up to 10% of ulcerative colitis patients may demonstrate a diffuse chronic duodenitis.15 Keep in mind, however, that IBD is a primary consideration only when the changes are “focally enhanced” (Figs. 3.77 and 3.78) (See Focally Enhanced Gastritis, Stomach Chapter) or are accompanied by mucosal granulomata, or if lower gastrointestinal tract disease is present. Sampling error in the duodenum may result in the lack of specific features, and this can raise a host of other differential diagnoses, such as medication-induced changes, upstream gastric disease, and other inflammatory or immune-regulated disorders. One such example is psoriasis, which may show mild duodenal inflammation and mast cell infiltration.16–18 It is perhaps, therefore, best not to speculate on the etiology of a mild nonspecific duodenitis in the absence of clinical information. Rather, simple documentation of the mild abnormality and acknowledgement of pertinent negatives are sufficient.

Figure 3.75 Chronic inflammation, nonspecific, duodenal giardiasis. Chronic inflammation in the small bowel is often nonspecific, but routine careful examination of all the tissue compartments may yield diagnostic findings. This example shows a prominent lymphoid aggregate and some dilated lacteals (arrow) in this duodenal biopsy. The tissue findings are nonspecific, but the diagnosis resides in the space between the villi (arrowhead).

Figure 3.76 Chronic inflammation, nonspecific, duodenal giardiasis Higher magnification of the indicated area in the previous figure reveals the protozoa Giardia.

Figure 3.77 Chronic inflammation, focally enhanced, duodenal Crohn disease. This biopsy shows a pattern of focally enhanced inflammation in a patient with duodenal Crohn disease. The findings are nonspecific and consist of localized inflammation, which should be interpreted in the proper clinical setting.

Figure 3.78 Chronic inflammation, nonspecific, duodenal Crohn disease. Higher magnification of the previous figure shows cryptitis (arrowheads) consistent with the patient’s known history of duodenal involvement by Crohn disease.

SAMPLE NOTE: SMALL BOWEL WITH MILD CHRONIC INFLAMMATION, BUT NO OTHER SPECIFIC FEATURES:

Small Bowel, Biopsy:

• Small intestinal mucosa with mildly increased lamina propria chronic inflammation, nonspecific.

• Negative for intraepithelial lymphocytosis or villous blunting.

CRYPT ARCHITECTURAL DISTURBANCE PATTERN

Figure 3.79 Crypt architectural disturbance pattern. This pattern encompasses the general features of “chronicity” including crypt distortion and branching (pictured here), crypt dropout, crypt shortfall, and pyloric metaplasia.

CHECKLIST: Etiologic Considerations for the Architectural Disturbance Pattern

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Diaphragm Disease

Diaphragm Disease

Ischemia

Ischemia

Graft Versus Host Disease

Graft Versus Host Disease

Acute Medication Reaction (Mycophenolate Mofetil and Mycophenolic Acid)

Acute Medication Reaction (Mycophenolate Mofetil and Mycophenolic Acid)

Allograft Rejection

Allograft Rejection

Radiation Duodenitis

Radiation Duodenitis

Pouchitis and Pouch-Related Changes

Pouchitis and Pouch-Related Changes

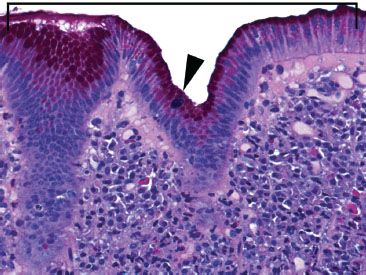

At scanning magnification, the appearance of crypt architectural disturbance can be seen as: crypt distortion, crypt dropout, crypt shortfall with or without basal lymphoplasmacytosis, or microcrypt formation (Fig. 3.79). Note that this pattern is exclusive of villous architectural changes (i.e., villous blunting), which, instead, is a feature of malabsorption pattern and confers a different group of differential diagnoses. Although some might consider villous blunting a feature of chronic injury, isolated architectural disturbances of the villi should be investigated as a malabsorption pattern. Furthermore, although many of these features indicate chronic injury, this pattern spans a histologic spectrum from subtle to striking, encompassing features from the earliest crypt disturbance (a single withered crypt) to marked crypt distortion. Crypt architectural disturbance is a nonspecific pattern of injury, the etiology of which encompasses IBD, mesenteric ischemia, graft versus host disease, allograft rejection, short gut syndrome, radiation duodenitis, and (ileal) pouchitis. Incisive readers will note that crypt disturbances are a minor histologic pattern in many of these entities, and indicate chronic injury. Accordingly, examination for other primary features (e.g., increased apoptotic bodies in graft vs. host disease) and correlation with clinical circumstances are required to arrive at an etiology.

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

Crohn disease is a chronic idiopathic inflammatory disorder characteristically involving the distal 15 to 25 cm of the terminal ileum; however the gastrointestinal manifestations of Crohn disease are remarkably diverse and may include variations such as ileocolic Crohn disease (30% to 50% of patients with Crohn disease), localized or extensive disease of the small bowel (25% to 50%), isolated Crohn colitis (15% to 30%), anorectal Crohn disease (5% to 19%), or gastric, esophageal and duodenal Crohn disease (5% to 30%).19–22 Histologically, the disease manifests in a patchy distribution with a combination of activity (cryptitis, crypt abscess, erosion, and ulceration) and chronicity (villous blunting, crypt architectural distortion, crypt dropout, crypt shortfall, basal lymphoplasmacytosis, increased lamina propria chronic inflammation, pyloric metaplasia, transmural lymphoid aggregates, and neuromuscular hyperplasia&emdash;with or without granulomata). For an expanded discussion on the general features of Crohn disease, see also Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Chronic Colitis Pattern, Colon Chapter.

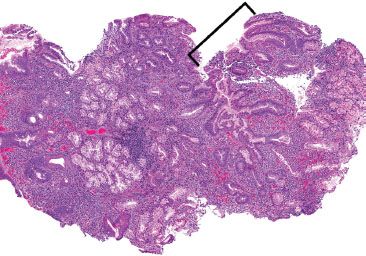

In the duodenum, Crohn disease produces typical lesions in approximately 0.5% to 4% of patients.23 These lesions usually coexist with ileal involvement, and may extend proximally and distally to involve the stomach or jejunum. By comparison, “regional jejunitis” rarely coexists with duodenal disease and may locally or diffusely involve the jejunum. Progressive transmural inflammation with scarring and deep ulceration may ultimately lead to symptoms associated with intestinal obstruction, perforation, bleeding, or fistula formation. When obstruction develops, it usually does so in the distal ileum, and deep linear ulcers or fistulae may give rise to profound gastrointestinal bleeding. Gross and full-thickness microscopic examination of the small bowel are considered the gold standard for diagnosis. Gross pathology shows thickening of the bowel wall, fistula formation, strictures, serpiginous ulcers, aphthous ulcers, and creeping mesenteric fat. The corresponding histology shows a combination of variable activity (cryptitis, villitis, crypt abscess, erosion, and ulcer) and chronicity (villous blunting, crypt architectural distortion, crypt dropout, crypt shortfall, basal lymphoplasmacytosis, increased lamina propria chronic inflammation, pyloric metaplasia, transmural lymphoid aggregates, and neuromuscular hyperplasia&emdash;with or without granulomata) (Figs. 3.80–3.87).

FAQ: What is “creeping fat?”

Answer: The antimesenteric serosal surface of the small bowel and colon is usually smooth and devoid of adipose tissue. In Crohn disease, repeated cycles of transmural damage can result in an irregular antimesenteric serosal surface composed of prominent fibrosis and fat (“creeping fat”). This creeping fat is used by surgeons to identify the extent of affected bowel for resection. In addition, this finding should be documented at the grossing bench as it can help differentiate Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis.

Figure 3.80 Crypt architectural disturbance, Crohn disease. The crypt architectural disturbances are evident at low magnification. Normally, the crypts rest directly on the muscularis mucosae. In this example, the base of a crypt falls short of touching the muscularis mucosae. This gap between the muscularis mucosae and the crypt is called “crypt shortfall” (arrow). Also, note the irregularly shaped crypts, or abnormal crypt configuration, in addition to areas of total glandular loss, or “crypt dropout.”

Figure 3.81 Crypt architectural disturbance, Crohn disease. Crypt architectural disturbances are seen with irregularly shaped crypts and bifid branching crypts (arrowhead). Note also the presence of cryptitis within this same crypt and the loosely-formed granuloma (arrow).

Figure 3.82 Crypt architectural disturbance, Crohn disease. Residual villous projections are present, but the major pattern here is crypt architectural disturbances, including crypt distortion, crypt shortfall, and crypt dropout. The lamina propria is expanded with increased chronic inflammation and prominent pyloric metaplasia (arrowheads) is present.

Figure 3.83 Crypt architectural disturbance, pyloric metaplasia. Pyloric-type glands are normally limited to the pylorus at the junction of the stomach and small bowel. When seen in the terminal ileum, these metaplastic glands indicate chronicity.

Figure 3.84 Crypt architectural disturbance, pyloric metaplasia. These pyloric glands have abundant foamy-to-clear cytoplasm and small, round or ovoid nuclei that may be flattened against the basement membrane.

Figure 3.85 Crypt architectural disturbance, pyloric metaplasia. Although pyloric metaplasia (arrowhead) indicates chronicity, it is not specific for Crohn disease, and can be found in other chronic conditions, such as diaphragm disease of the terminal ileum.

Figure 3.86 Crypt architectural disturbance, Crohn disease. This example shows crypt distortion and expansion of the lamina propria with an inflammatory infiltrate. Areas of pyloric metaplasia (arrow) are also present.

Figure 3.87 Crypt architectural disturbance, Crohn disease. Although chronic injury features are evident at low power, higher magnification is required to see areas of active inflammation (activity) indicated by neutrophils. Seen here are cryptitis (arrow) and lamina propria acute inflammation (arrowhead).

FAQ: Does involvement of resection margins by Crohn disease have prognostic significance?

Answer: No.

The status of resection margins is not predictive of disease recurrence.24 Postoperative recurrence of Crohn disease is more common in patients with greater disease extent, perforating disease, and medically refractory Crohn disease.25

DIAPHRAGM DISEASE

NSAIDs cause a wide spectrum of histologic changes in the small bowel, some of which are segment specific, such as diaphragm disease of the terminal ileum. Mild lesions consist of superficial erosions with nonspecific neutrophilic, eosinophilic and plasmacytic infiltrates. These erosions may be multiple, can coalesce forming deep ulcers, and may result in hemorrhage. Repeat cycles of ulceration and healing can cause submucosal scarring and web-like mucosal septa that project into the lumen. These resulting circumferential stenosing lesions appear as multiple diaphragm-like narrowings and are more commonly seen in the distal small bowel, particularly the terminal ileum (Figs. 3.88 and 3.89). Accordingly, the patients often present with a surgically emergent obstruction. This so-called diaphragm disease can be accompanied by a wide array of additional abnormalities, including crypt architectural disturbances mimicking IBD, eosinophilic enteritis, enteritis cystica profunda, and neuromuscular and vascular hamartoma-like changes (Figs. 3.90–3.92).26 By comparison, NSAID injury in the proximal small bowel often results in subtle and nonspecific reactive duodenopathy-type changes, rather than chronic architectural changes. See also Malabsorption Pattern, this chapter. A diagnosis of diaphragm disease can be suggested by the endoscopic or pathologic findings but requires correlation with the patient’s medication list for definitive diagnosis. Distinction from ileal Crohn disease can be particularly challenging if a history of NSAID use cannot be documented; in general, there is minimal chronic inflammation in NSAID-associated injury, whereas it is abundant in Crohn enteritis. Anecdotally, we have seen surreptitious NSAID abuse lead to segmental resection of obstructing diaphragms; family members of the patients may be able to provide the clinical correlation in these cases.

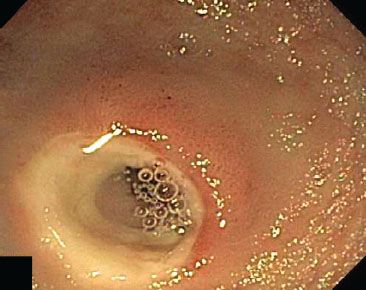

Figure 3.88 Diaphragm disease, endoscopic view. Chronic NSAID injury in the distal small bowel causes cycles of ulceration and healing that result in circumferential stenosing lesions (“diaphragms”) and can lead to obstruction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree