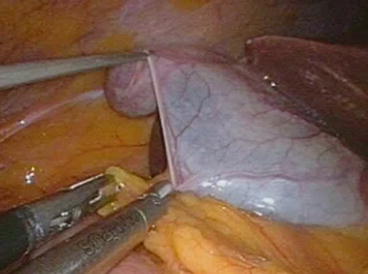

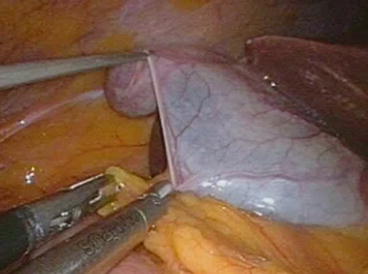

Fig. 4.1

Pre-shaped curved instruments reproduce open surgery triangulation

Fig. 4.2

5-mm chip-on-the-tip scopes reduce encumbrance within the access device

Fig. 4.3

Articulated scopes allow better inside view without collision with the working instruments and between operator and camera assistant’s hands

4.2.2 Dissection Technologies

Tissue dissection during SALC may be accomplished either by monopolar HF or by US devices. The authors believe that HF hooks should be preferred to HF energized scissors: hooking up tissues and their tenting before applying energy is of utmost relevance when traction and movement freedom are impaired, making the dissection safer . Ultrasonic dissection provides an almost bloodless field, preventing oozing from tissue division. Unfortunately, the use of disposable US shears increases costs considerably.

4.2.3 Surgical Technique

The patient lays legs apart in supine position, with the surgeon standing between the legs (French position) and the assistant on the patient’s left side.

Access to the peritoneal cavity is obtained through a skin incision of about 15–20 mm either right around the upper edge of the umbilicus as in most CLC (Fig. 4.4) or dividing longitudinally the umbilicus itself. In the latter case, the umbilicus is grasped at its base everted. The skin incision is made within the umbilical fold and an approximately 20-mm fascia incision is created to allow the introduction of the single site access device. Pneumoperitoneum is then established. Three instruments are generally introduced through the single access device: a 5-mm 30° scope and two 5-mm working instruments. Those instruments, a grasper and an energized device, can be straight or curved (Fig. 4.5). Ten-millimeter optics may be used as well, but this will further reduce the working room and instrument handling.

Fig. 4.4

Appearance of the skin incision at the end of SALC

Fig. 4.5

Grasping and dissection instruments have an almost parallel direction within the operating field. The TriPort® and Quad-port® (Olympus) devices allow the passage of a further 1.8-mm grasper that enhances traction, thus improving exposure

Exploration of the supramesocolic space and the operating field is carried out first, checking the gallbladder and the possibility to achieve a good exposure of the Calot’s triangle.

Gallbladder dissection is accomplished either after preparation of the cystic duct and artery or with a fundus-first technique, by high-frequency hook/scissors or ultrasonic shears.

When straight instruments are employed, the one in the right hand is used to retract the gallbladder ampulla to the right and cephalad.

The Calot’s triangle is dissected with the left-hand instrument in order to achieve the Strasberg critical view of safety visualizing and dissecting free the cystic duct and artery. In such a case, the working instruments cross, and there is never the possibility to achieve optimal instrument triangulation within the operative field. The cystic artery is either divided between clips or closed and divided by ultrasonic shears, whereas the duct is preferably secured with titanium or absorbable clips (Fig. 4.6). Use of 5-mm-diameter disposable clip appliers is advised. Even though cystic ducts larger less than 5 mm in diameter may be closed-divided by ultrasonic shears, thus reducing need for instrument exchange, division of the duct by US energy was never performed within RCTs in order to avoid possible bias. Gallbladder dissection from the gallbladder fossa is accomplished in the usual manner, and the specimen is removed with a retrieval bag or through the access device, thus avoiding abdominal wall contamination. In case of larger stones, gallbladder extraction through the access device may be laborious and time consuming, and an extension of the parietal incision may be required.

Fig. 4.6

An absorbable clip is applied on the cystic duct before its division by ultrasonic shears

When the fundus-first technique is carried out, the gallbladder should be dissected preferably by ultrasonically activated shears, thus avoiding oozing due to not performing prior cystic artery ligature. With this technique, once the gallbladder is fully mobilized, traction on the infundibulum is improved, allowing a better visualization of the Calot’s triangle and identification of anatomical structures and an easier dissection of cystic artery and duct. Nevertheless, during fundus-first dissection, maximum care should be taken while approaching the infundibulum, in order to avoid injuries to hidden posterior structures.

In authors’ view, the optimal instrument combination to accomplish SALC safely and faster is achieved by using one pre-shaped curved instrument for grasping and one straight instrument for dissection (either US scissors or HF hook). Not only curved graspers may be kept outside the operating field while retracting the gallbladder, also their bent part may be used for gentle liver traction without risk of injuries. Furthermore, straight dissection instruments are easily guided within the operating field, and the combined use of pre-shaped curved instruments and straight instruments, which are usually different in length, decreases surgeon’s hand conflict.

A further 5-mm cannula may be placed on the upper left quadrant to introduce a fourth instrument, thus enhancing exposure or dissection: in such a case the operation should be considered as converted to reduced port laparoscopy.

At the end of the procedure, the fascia incision should be carefully closed, to minimize incisional hernia occurrence. Compared to the closure of laparoscopic incisions after CLC, fascial suture through the wider skin incision of SALC should be theoretically easier; nevertheless, this seems not to have any positive effect on the incidence of incisional hernia.

4.3 Drawbacks, Tips and Tricks, and Technical Variations

Reduced degrees of freedom of working instruments, lack of triangulation, poor working room, and fencing effect of instruments that have an almost parallel direction when introduced through a single access device are the limits of single access laparoscopy. During SALC, these limits entail three major drawbacks: restrained instrument movements, poor traction, and insufficient exposure. The latter is mainly caused by the difficulty in providing optimal liver retraction, especially when straight instruments are used: their direction within the operating field does not allow lifting up the inferior aspect of the liver without puncturing or tearing the parenchyma.

View may be compromised by in-line viewing, caused by both the proximity of optic and working instruments and lack of an optimal angle of view. This may affect surgical judgment and depth perception and reduces view of target tissues as well. Furthermore, standard length, straight telescopes, and working instruments may hamper each other, when handled. The same may happen with the hands of the two surgeons.

While working with straight instruments, the surgeon must learn to operate on a mirror image because the right hand is controlling the left-sided instrument on the screen and vice versa.

Traction and improved exposure may be achieved by transfixing stay sutures or internal retractors. A monofilament nylon suture with straight needle is passed through the abdominal wall right below the costal arch, passed through the fundus, hence back through the abdominal wall to suspend the gallbladder by anchoring it to the wall. A second stay suture may be passed in similar fashion through the infundibulum to provide lateral traction, thus achieving a wider opening of Calot’s triangle. The EndoGrab® is a small 2-component internal retractor featuring springs and hooks that may be introduced through the access device, used to make traction by anchoring tissues, with ease to be replaced according to the surgeon’s needs [8]. One component is used to grab the fundus; the second component’s hook is used to hang the gallbladder up to the wall. In Authors’ opinion, internal retractors should be preferred: use of stay sutures in some way contravenes the principle of mobile exposure, by preventing the surgeon from moving the Hartmann’s pouch while attempting to expose the Calot’s triangle. Other authors argue that transfixing sutures also increase risk of gallbladder perforation, an event that may cause bile spillage, often associated with pain (due to peritoneal irritation and inflammation) and potential postoperative infections. Nevertheless, there is no evidence that stay sutures increase postoperative morbidity after SALC.

Telescopes with articulating tips and bent instruments help in minimizing conflict during surgical maneuvers and enhance visualization of the operative field. Use of instruments different in length may prevent hand conflict [9]. A further physical constraint encountered during SALC is the frequent interference of the light cable with other instruments: use of optical systems with light cable connection located on their head is advised whenever possible.

A wider incision allows more freedom in instrument handling, which is particularly useful when straight instruments are used to carry out the operation. Lirici et al. demonstrated a correlation between operating time and umbilical incision length: the wider the incision, the less the operating time [1].

4.3.1 SALC-POP (Plus One Port) Technique

Kanehira (personal report, 2010) proposed the use of one needlescopic grasper (1.8–3 mm in diameter) to provide a clearer view of the operative field, instrument triangulation, and faster dissection or coagulation when bleeding occurs, a technique that may be applied also to accomplish other single access procedures [10]. Present needlescopic and minilaparoscopy graspers are nitinol or surgical steel instruments with good grasping capability. A needlescopic grasper is introduced through the upper left quadrant of the abdomen with an optimal working angle. Its insertion does not require the placement of a cannula and is not considered a conversion to reduced port laparoscopy.

4.3.2 Single Access Robotic Cholecystectomy

The introduction of the novel da Vinci® robotic single-port platform allows performing SALC overcoming most of its limits, relating to instrument triangulation, ergonomics, and surgical exposure. The single-port platform elaborates the images giving the surgeon the feeling of not performing surgery on a mirror image while working with straight instruments that cross within the operative field. Results from a prospective longitudinal observational study conducted on 100 consecutive da Vinci single access cholecystectomies [11] with feasibility without conversion and safety as primary end point showed that the robotic approach is safe and allows a quicker overcoming of the learning curve phase. Conversion rate was minimal with mean total operating time of 72 min and console time of 32 min. Nevertheless, operating time does not decrease by increasing surgeon’s experience. After subjective evaluation through a questionnaire collecting surgeons’ opinions, single access robotic cholecystectomy was judged more complex than CLC but easier then manual SALC.

4.4 The Evidence

Since 2010 several randomized trials [1, 9–23], meta-analyses [24–27], and systematic review [28] comparing single access laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SALC) and conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy (CLC) have been published with the following end points: feasibility and safety, pain scores, cosmetics, satisfaction scores, and quality of life. Details of patient study groups and interventions from 14 randomized trials are shown in Table 4.1. In all studies but one, [14] acute cholecystitis was considered an exclusion criterion.

Table 4.1

Details of patients study groups and interventions from 14 RCTs

Authors | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Primary end point | Operation | Study group | Control group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sample size | Sex ratio (F/M) | Mean age | Mean BMI | Sample size | Sex ratio (F/M) | Mean age | Mean BMI | |||||

Ostlie et al. 2013 [12] | Age <18 scheduled for elective cholecystectomy | Cholecystitis weight >100 kg | Operative time | SALC (SILS Port, Covidien) vs. CLC (4-port) | 30 | 8/2 | 14 + −3.2 | nr | 30 | 8/2 | 13.3 + −3.3 | nr |

Marks et al. 2013 [13] | Age 18–85, BMI <45, gallstones, polyps, biliary dyskinesia with an ejection fraction <30 % | Pregnancy, acute cholecystitis, previous right subcostal or upper midline incision, preoperative indication for ERCP or for intraoperative biliary imaging, ASA >3, peritoneal dialysis, presence of umbilical hernia, previous umbilical hernia repair | Safety | SALC (SILS Port, Covidien) vs. CLC (4-port) | 119 | 91/28 | 45.8 | 29 | 81 | 57/24 | 44 | 30.9 |

Leung et al. 2012 [14] | Age >18 years old, any patients with an indication for cholecystectomy | Pregnancy, <18 years old, porcelain gallbladder | Cosmesis Pain scores | SALC (device not reported) vs. CLC | 36 | *86.7 %F | 41.8 | 28.7 | 43 | *61%F | 52.3 | 28.4 |

Zheng et al. 2012 [15] | Age >18, BMI <28, no significant comorbidities, cholelithiasis or polyps | Jaundice, suspected or verified stones in the CBD, acute cholecystitis, perforation of the gallbladder, previous abdominal operations | Unclear | SALC (ASC TriPort) vs. CLC (3-port) | 30 | 17/13 | 43.6 | 24.7 | 30 | 14/16 | 46.8 | 25.9 |

Sinan et al. 2012 [9] | Cholelithiasis or polyps, no previous upper gastrointestinal surgery, BMI <40 | Acute cholecystitis, pancreatitis, BMI >40, previous upper gastrointestinal surgery | Pain scores | SALC (SILS port, Covidien) vs. CLC | 17 | 13/4 | 48.5 | 27.3 | 17 | 9/8 | 48.7 | 27.2 |

Lirici et al. 2011 [1] | Age 18–75, BMI ≤30, no previous upper GI surgery, gallstones, ASA ≤3, Nassar grades I–III | BMI >30, previous upper GI surgery per right colonic surgery, acute cholecystitis, bile duct stones, pancreatitis, ASA >3, Nassar grade IV | QoL (LoS, pain scores, cosmetic results, SF-36) | SALC (TriPort, Olympus) vs. CLC (4-port) | 20 | 14/6 | 45 | 25 | 20 | 14/6 | 50 | 27 |

Asakuma et al. 2011 [22] | Age 20–85, clinically benign gallbladder disease | CBD stones, previous upper abdominal surgery, emergency presentation | Pain scores (VAS) | SALC (surgical glove port) vs. CLC (4-port) | 24 | 13/11 | 57 | 24 | 25 | 12/13 | 66 | 24.1 |

Postoperative analgesic use | ||||||||||||

Ma et al. 2011 [17] | Age 18–85, gallstones, polyps, biliary dyskinesia, BMI <40, creatinine <2 mg/dL, AST/ALT <5× upper limit of laboratory normal | Choledocholithiasis, acute cholecystitis, gallstones >2.5 cm in greatest diameter | Pain scores (VAS) | SALC (ASC TriPort) vs. multi-incision (4-port) | 21 | nr | 57.3** | 28.2 | 21 | Nr | 45.8** | 30.7 |

Aprea et al. 2011 [19] | Clinical symptoms and EUS evidence of gallstones | Previous abdominal surgery, signs of acute cholecystitis or choledocholithiasis or acute pancreatitis, ASA ≤3, BMI >30 | Unclear | SALC (TriPort, Olympus) vs. CLC (3-port) | 25 | 16/14 | 45.5 | 25.9 | 25 | 19/6 | 44.0 | 23.7 |

Cao et al. 2011 [20] | No sign of acute choledocholithiasis or acute pancreatitis, no epigastric surgery, ASA <3, age <70, BMI <30 | Unclear | 3 separate ports placed through the same umbilical incision, through separate fascial incisions vs. CLC (3-port) | 57 | 34/23 | 62.2 | 28.6 | 51 | 29/22 | 59.7 | 29.1 | |

Bucher et al. 2011 [16] | Elective patients with symptomatic gallbladder stones, history of cholecystitis, history of common bile duct stone migration and/or biliary pancreatitis, age >18 | Acute gallbladder disease, contraindications to pneumoperitoneum, cirrhosis, mental impairment | Cosmetic result | SALC (ASC TriPort) vs. CLC (4-port) | 75 | nr | 42 | 26 | 75 | Nr | 44 | 25 |

Lai et al. 2011 [18] | Age 18–80, symptomatic gallstones or gallbladder polyps | ASA IV or V, contraindication for laparoscopy, Mirizzi syndrome, suspected CBD stones, suspected malignancy, previous upper abdominal surgery, patients on long-term anticoagulant treatment, previous history of cholangitis or cholecystitis, gallstone > 3 cm, imaging diagnosis of contracted gallbladder or chronic cholecystitis | Pain scores | SALC (SILS port, Covidien) vs. CLC (4-port) | 24 | 16/8 | 51.7 | 25 | 27 | 16/11 | 54.3 | 24.4 |

Tsimoyiannis et al. 2010 [23] | BMI <30, cholelithiasis, ASA 1–2 | BMI >30, sign of acute cholecystitis or attacks of acute pancreatitis, ASA >2 | Pain scores | SALC (3 separate ports placed through the same umbilical incision, through separate fascial incisions) vs. CLC (4-port) | 20 | 15/5 | 49.2 | nr | 20 | 19/1 | 47.9 | nr |

Lee et al. 2010 [21] | Symptomatic cholelithiasis, ASA 1–2 | Acute cholecystitis, clinical evidence of CBD stones, severe obesity, previous upper abdominal surgery | Pain scores | SALC (Quad-port, LAGIS) vs. multi-incision minilaparoscopic (5-port) | 35 | 22/13 | 51 | 24.2 | 35 | 20/15 | 53.3 | 25.8 |

Body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 was an exclusion criterion in five studies [1, 15, 19, 20, 23], ≥40 kg/m2 in three [9, 17, 21], and ≥45 kg/m2 in one [13]. In four studies a high BMI value was not considered an exclusion criterion, but despite this, the mean BMI of those studies never exceeds 30 kg/m2 [14, 16, 18, 22].

Pain score was the primary end point in nine studies [1, 9, 14, 17–19, 21–23], cosmetic results in three [1, 14, 16], and operative time and safety each in one [12, 13]. Primary end points were not clearly expressed in two [15, 20].

Mortality and morbidity rates and operating time were secondary end points in all studies but one [23].

In 11 out of 14 studies, operating time was significantly longer in the study group. SALC lasted an average of 20 min more than CLC. Postoperative length of stay did not differ significantly in both patient groups, nor was the mortality rate, which was 0 in all studies (Table 4.2). Morbidity rate was similar in both groups, as was the incidence of bile duct injuries. However, despite this lack of significance, the overall incidence of adverse effects was a little higher in SALC group, with a pooled OR of 1.15 (95 % CI 0.740–1.827), 1.21 (95 % CI 0.83–1.76), and 1.21 (95 % CI 0.73–2.01) as respectively reported in Pisanu, Hao, and Garg meta-analyses.

Table 4.2

Operative time, conversion, morbidity and mortality rate, and lenght of stay in 14 RCTs

Authors | Intervention group | Control group | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Operative time | Postoperative length of stay | Morbidity rate (%) | Conversion to open surgery/to conventional LC (%) | Mortality rate | Operative time | Postoperative length of stay | Morbidity rate % | Conversion to open surgery (%) | Mortality rate | |

Ostlie et al. 2013 [12] | 68.6 ± 22.1* | 1.01 ± 0.54 days | 0 | 0 | 0 | 56.1 ± 22.1* | 0.90 ± 0.12 days | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Marks et al. 2013 [13] | 56.8** | nr | 45 | 0.84/0 | 0 | 45.3 ** | nr | 36 | 0 | |

Leung et al. 2012 [14] | 72.9***

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |||||||||