This article reviews the data for diagnostic and uncomplicated therapeutic upper endoscopy, which show it is safe and effective to perform the procedure under moderate sedation with a combination of benzodiazepine and opioids. For more complex procedures or for superobese patients anesthesia support is recommended. Performing endoscopy in this population should alert providers to plan carefully and individualize sedation plans because there is no objective way to quantify this risk pre-endoscopically.

Key points

- •

There is little evidence regarding endoscopic sedation in obesity and obstructive sleep apnea.

- •

Moderate sedation is likely safe for diagnostic and simple therapeutic procedures in the general obese and bariatric populations.

- •

Anesthesia support should be considered for more complicated therapeutic procedures and in the superobese.

Obesity has become an epidemic health problem worldwide. Defined as a body mass index (BMI) of greater than or equal to 30 kg/m 2 , obesity is divided into class I (BMI 30–34.9 kg/m 2 ), class II or severe obesity (BMI 35–39.9 kg/m 2 ), and class III or morbid obesity (BMI >40 kg/m 2 ). Some surgical literature further breaks down class III obesity into superobese, which represents those with BMI of greater than or equal to 45 or 50 kg/m 2 . In 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that 33% of adults ages 18 years and older were overweight (BMI >25 kg/m 2 ), and 13% were obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ). In the United States, this problem has become even more severe with more than half of adults ages 20 years and older being overweight and 34.9% being obese as of 2012. To date, multiple conditions have been shown to be associated with obesity, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, stroke, osteoarthritis, and sleep apnea. Additionally, multiple gastrointestinal diseases, including gallbladder disease, esophageal cancer, and colon cancer, have been demonstrated to be more prevalent in patients with a higher BMI. As a result, all gastroenterologists will inevitably encounter an increase in the number of obese patients in their practice who are undergoing endoscopy.

Sedation is an integral component of every endoscopic examination. Defined as a drug-induced state in which the level of consciousness is depressed, sedation provides a relief in patients’ discomfort and anxiety, and allows proceduralists to focus on the endoscopic work. Four stages of sedation have been described: minimal, moderate, deep, and general anesthesia ( Table 1 ). Generally, most diagnostic and uncomplicated therapeutic upper endoscopy and colonoscopy can be successfully performed under moderate sedation, formerly known as conscious sedation. During moderate sedation, patients respond purposefully to verbal commands or tactile stimulation. For longer and more complex procedures, however, deeper levels of sedation may be required. These include deep sedation in which patients cannot be easily aroused but may respond purposefully to painful or repeated simulation and general anesthesia in which patients are unarousable to painful stimuli. To appropriately choose the level of sedation for each procedure, multiple factors need to be taken into an account. These include patient’s age, comorbidities, concurrent medications, pain tolerance, and the type of endoscopic procedure being performed. This article explores the medical literature on the effect of obesity and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) on endoscopic sedation.

| Responsiveness | Airway | Spontaneous Ventilation | Cardiovascular Function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal sedation | Normal response to verbal stimulation | Unaffected | Unaffected | Unaffected |

| Moderate sedation | Purposeful response to verbal or tactile stimulation | No intervention required | Adequate | Usually maintained |

| Deep sedation | Purposeful response after repeated or painful stimulation | Intervention may be required | May be inadequate | Usually maintained |

| General anesthesia | Unarousable even with painful stimuli | Intervention often required | Frequently inadequate | May be impaired |

Obesity and sedation

Traditionally, a higher BMI was thought to be associated with an increased risk during procedural sedation. This may be due to sleep apnea, pulmonary hypertension, and restrictive lung disease, which are more common in patients with obesity. Additionally, airway management in obese patients may prove to be more difficult due to rapid oxygen desaturation, challenges with mask ventilation and intubation, and increased susceptibility to the respiratory depressant effects of sedatives. As a result, many institutions require an anesthesia consultation on all patients with a BMI of 40 and higher before any endoscopic procedures to plan out the safest and most efficacious method of sedation.

Nonbariatric Obese Population

Although anecdotally obese patients are believed to be at higher risk for procedural sedation, this perception is not extensively backed up by the medical literature. In fact, the concept of BMI being a risk factor for sedation-related adverse events (SRAEs) has only recently gained an interest among gastroenterologists. In large national studies using the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative National Endoscopic Database (CORI-NED) in 2004 and 2007, BMI was not included in the analyses as a potential risk factor for cardiopulmonary unplanned events during endoscopy. In these studies, patient’s age, male gender, higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification grade, inpatient status, trainee participation, and routine use of oxygen were associated with a higher incidence of cardiopulmonary unplanned events.

Available data on the use of sedation in obese patients remained quite sparse. Most were small case series and mainly evaluated the obese patients who were undergoing advanced endoscopic procedures or upper endoscopy before a bariatric surgery. Dhariwal and colleagues demonstrated in a case series of 82 subjects undergoing diagnostic upper endoscopy that a BMI greater than 28 was a risk factor for hypoxemia. In this study, other risk factors included age greater than 65 years and anemia with a hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL. Similarly, Qadeer and colleagues found that a higher BMI was an independent risk factor for hypoxemia in subjects with ASA classes I and II. In this study, 79 subjects undergoing outpatient upper endoscopy, colonoscopy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) were included. Other risk factors in this study were age older than 60 years and the total dose of narcotics. Subsequently, Berzin and colleagues conducted a study to assess risk factors of SRAEs during ERCP. The study included 528 subjects undergoing ERCP under deep sedation and general anesthesia. Higher ASA class and BMI higher than 30 were found to be associated with increased risk of cardiopulmonary unplanned events during ERCP. Last but not least, to better understand the optimal method of sedation for patients with a higher BMI, Mahan and colleagues performed a randomized trial of 100 morbidly obese subjects (BMI≥40) who underwent upper endoscopy before bariatric surgery. In this study, the subjects were randomized to endoscopist-administered sedation with benzodiazepines and narcotics versus anesthesiologist-administered sedation with propofol. The study showed that significantly fewer patients in the anesthesiologist-administered sedation group remembered gagging during the procedure and/or complained of throat pain after the procedure. Therefore, it was concluded that deep sedation should be considered in patients undergoing preoperative upper endoscopy before bariatric surgery. Of note, in this study, hypoxemia and other cardiopulmonary unplanned events were not assessed, potentially because of the small sample size. Therefore, no conclusions regarding procedural safety can be derived from this study. Of note, to date, there have been no studies that specifically assess the safety of performing endoscopy under moderate sedation in the superobese population.

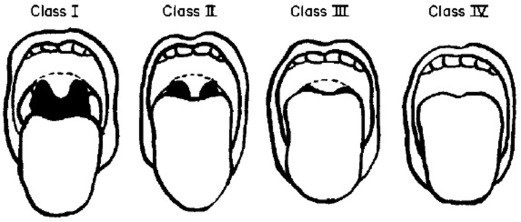

Both anatomic and metabolic factors likely play a role in sedation challenges in the obese population. An altered airway anatomy found in obese patients has been shown to be associated with difficult endotracheal intubation. In 1985, Mallampati and colleagues developed and validated the Mallampati score to predict the ease of endotracheal intubation. The test consisted of a visual assessment of the distance from the tongue base to the roof of the mouth ( Figs. 1 and 2 , Tables 2 and 3 ). A higher Mallampati score (class 3 or 4) has been shown to be associated with more difficult intubation. Subsequently, anesthesia literature has demonstrated an association between a higher Mallampati score and a higher BMI to a higher risk of intubation. However, to date, there have been no studies that specifically demonstrate that an advanced Mallampati score leads to increased risk of sedation during endoscopy. In addition to anatomic factors, obese patients seem to metabolize sedative agents differently compared with lean patients. Specifically, binding and elimination of drugs and volumes of distribution seem more unpredictable in obese patients. Higher BMI is also likely associated with higher adipose mass, a reduction in total body water, higher glomerular filtration rate and normal hepatic clearance, which may lead to higher sedative dose requirement and thus increased sedation risks.

| Class 1 | Faucial pillars, soft palate, and uvula could be visualized |

| Class 2 | Faucial pillars and soft palate could be visualized but uvula was masked by the base of the tongue |

| Class 3 | Only soft palate could be visualized |

| Class I | Soft palate, uvula, fauces, pillars visible |

| Class II | Soft palate, uvula, fauces visible |

| Class III | Soft palate, base of uvula visible |

| Class IV | Only hard palate visible |

Given the sparse literature on a direct association between a higher BMI and increased SRAEs, most society guidelines on sedation in obesity are based on expert opinion. The ASA Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Nonanesthesiologists mentioned that some pre-existing comorbidities may be related to adverse outcomes in patients receiving either moderate or deep sedation. These risk factors include significant obesity, especially if it involves the neck and facial structures. Similarly, the American Gastroenterological Association Institute review of endoscopic sedation recommended the use of an anesthesia professional for patients who are morbidly obese (BMI≥40). However, this is an expert opinion only and no supportive evidence was provided.

Bariatric Population

With the worsening obesity epidemic, the number of bariatric surgeries being performed has also increased. In 2013, about 179,000 bariatric surgeries were performed in the United States. Of these, more than one-third were Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). Although RYGB results in relatively durable weight loss and an improvement in presurgical comorbidities, postoperative complications, including anastomotic leak, gastrogastric fistula, marginal ulceration, and weight regain, are not uncommon. To manage these complications effectively, an endoscopic examination is usually required.

Anecdotally, bariatric patients have been observed to require higher sedative doses than those without a history of bariatric surgery, which leads to increased sedation risks. Some institutions require an anesthesia professional during any endoscopic examination performed on RYGB patients, which usually leads to longer wait time and greater economic burden. Similar to nonbariatric obese patients, data on the use of sedation in the bariatric population remain very sparse. Jirapinyo and colleagues reported that it was safe to perform upper endoscopy in the RYGB using moderate sedation, without anesthesia support. In this study, unplanned events were reported to be 1.6%, with 0.6% being cardiopulmonary unplanned events. This was relatively similar to the reported SRAEs in the general population, which varied from 0.13% in Silvis and colleagues to 0.9% in Sharma and colleagues. In this study, procedural length, and not absolute BMI, was the predictor of sedation requirement in the RYGB population. A subsequent matched cohort study from the same group showed that RYGB subjects required higher doses of sedation during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) than the non-RYGB with similar age, gender, and BMI. The investigators hypothesized that these findings could be due to an improvement in liver function after gastric bypass, which resulted in an improvement in liver metabolism of fentanyl and midazolam, which subsequently led to increased requirement of both sedatives during EGD.

Based on the currently limited available data, performing uncomplicated upper endoscopy in the RYGB seems to be safe and effective under endoscopist-directed moderate sedation. However, more studies are needed regarding sedation choice for colonoscopy and other endoscopic procedures.

Obesity and sedation

Traditionally, a higher BMI was thought to be associated with an increased risk during procedural sedation. This may be due to sleep apnea, pulmonary hypertension, and restrictive lung disease, which are more common in patients with obesity. Additionally, airway management in obese patients may prove to be more difficult due to rapid oxygen desaturation, challenges with mask ventilation and intubation, and increased susceptibility to the respiratory depressant effects of sedatives. As a result, many institutions require an anesthesia consultation on all patients with a BMI of 40 and higher before any endoscopic procedures to plan out the safest and most efficacious method of sedation.

Nonbariatric Obese Population

Although anecdotally obese patients are believed to be at higher risk for procedural sedation, this perception is not extensively backed up by the medical literature. In fact, the concept of BMI being a risk factor for sedation-related adverse events (SRAEs) has only recently gained an interest among gastroenterologists. In large national studies using the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative National Endoscopic Database (CORI-NED) in 2004 and 2007, BMI was not included in the analyses as a potential risk factor for cardiopulmonary unplanned events during endoscopy. In these studies, patient’s age, male gender, higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification grade, inpatient status, trainee participation, and routine use of oxygen were associated with a higher incidence of cardiopulmonary unplanned events.

Available data on the use of sedation in obese patients remained quite sparse. Most were small case series and mainly evaluated the obese patients who were undergoing advanced endoscopic procedures or upper endoscopy before a bariatric surgery. Dhariwal and colleagues demonstrated in a case series of 82 subjects undergoing diagnostic upper endoscopy that a BMI greater than 28 was a risk factor for hypoxemia. In this study, other risk factors included age greater than 65 years and anemia with a hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL. Similarly, Qadeer and colleagues found that a higher BMI was an independent risk factor for hypoxemia in subjects with ASA classes I and II. In this study, 79 subjects undergoing outpatient upper endoscopy, colonoscopy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) were included. Other risk factors in this study were age older than 60 years and the total dose of narcotics. Subsequently, Berzin and colleagues conducted a study to assess risk factors of SRAEs during ERCP. The study included 528 subjects undergoing ERCP under deep sedation and general anesthesia. Higher ASA class and BMI higher than 30 were found to be associated with increased risk of cardiopulmonary unplanned events during ERCP. Last but not least, to better understand the optimal method of sedation for patients with a higher BMI, Mahan and colleagues performed a randomized trial of 100 morbidly obese subjects (BMI≥40) who underwent upper endoscopy before bariatric surgery. In this study, the subjects were randomized to endoscopist-administered sedation with benzodiazepines and narcotics versus anesthesiologist-administered sedation with propofol. The study showed that significantly fewer patients in the anesthesiologist-administered sedation group remembered gagging during the procedure and/or complained of throat pain after the procedure. Therefore, it was concluded that deep sedation should be considered in patients undergoing preoperative upper endoscopy before bariatric surgery. Of note, in this study, hypoxemia and other cardiopulmonary unplanned events were not assessed, potentially because of the small sample size. Therefore, no conclusions regarding procedural safety can be derived from this study. Of note, to date, there have been no studies that specifically assess the safety of performing endoscopy under moderate sedation in the superobese population.

Both anatomic and metabolic factors likely play a role in sedation challenges in the obese population. An altered airway anatomy found in obese patients has been shown to be associated with difficult endotracheal intubation. In 1985, Mallampati and colleagues developed and validated the Mallampati score to predict the ease of endotracheal intubation. The test consisted of a visual assessment of the distance from the tongue base to the roof of the mouth ( Figs. 1 and 2 , Tables 2 and 3 ). A higher Mallampati score (class 3 or 4) has been shown to be associated with more difficult intubation. Subsequently, anesthesia literature has demonstrated an association between a higher Mallampati score and a higher BMI to a higher risk of intubation. However, to date, there have been no studies that specifically demonstrate that an advanced Mallampati score leads to increased risk of sedation during endoscopy. In addition to anatomic factors, obese patients seem to metabolize sedative agents differently compared with lean patients. Specifically, binding and elimination of drugs and volumes of distribution seem more unpredictable in obese patients. Higher BMI is also likely associated with higher adipose mass, a reduction in total body water, higher glomerular filtration rate and normal hepatic clearance, which may lead to higher sedative dose requirement and thus increased sedation risks.