Chapter 8 Revisional Bariatric Surgery

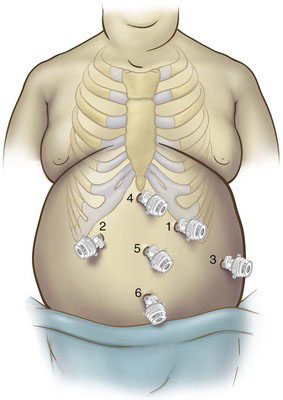

Patient positioning and placement of trocars

Laparoscopic access to the abdominal cavity is more safely accomplished with the use of an optical trocar placed away from previous incision sites. Most of the revisional bariatric surgeries can be carried out by positioning the trocars as shown in Figure 8-1.

Operative technique

Complications of Adjustable Gastric Banding

Conversion of Eroded LAGB to an LRYGB with Partial Gastrectomy

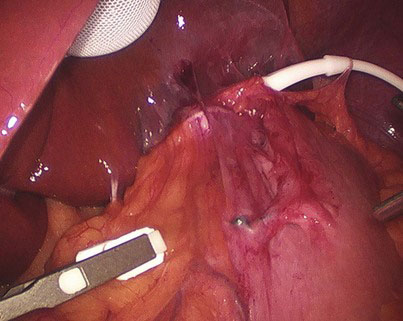

Upon entering the abdomen, there are often dense adhesions encountered between the left lobe of the liver and the area of the previously placed band. These adhesions are divided sharply, and a liver balloon retractor may facilitate exposure. Once the left lobe of the liver is elevated, the band tubing can be followed to the gastroplasty (Fig. 8-2). Gentle traction on the band tubing would lead the surgeon into the area of the buckle and surrounding reactive capsule. This reactive tissue can safely be divided sharply with scissors or energy source staying to the right of the gastroplasty. Often, because of chronic inflammation from the erosion, this is a very difficult plane to identify and dissect. Once the band is clearly identified, scissors can be used to divide and remove the band from around the stomach (Fig. 8-3). The band is removed, exposing the perforation. It is not necessary to divide the overlying gastroplasty because this tissue will be excised. It is usually easier to approach the dissection and mobilization of the fundus and midstomach rather than continuing the dissection in the right paraesophageal region, which is invariably hostile. Once the fundus is mobilized and the gastroesophageal junction and left bundle of the right crus of the diaphragm are identified, the dissection and gastric mobilization progress to the right. The gastrohepatic omentum is opened widely, and the caudate lobe of the liver, right crus of the diaphragm, and esophageal hiatus are identified. Dissection continues cephalad, to the right bundle of right crus of the diaphragm.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree