The rate of clinical understaging in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) after an initial transurethral resection (TUR) is significant, particularly for high-grade disease, and this has a major impact on prognosis. A repeat TUR, 2 to 6 weeks following the initial resection, is recommended in appropriately selected cases to avoid diagnostic inaccuracy and improve treatment allocation. This article summarizes the rationale and indications for performing a repeat TUR in NMIBC and also provides information regarding patient selection and technique.

Key points

- •

Understaging rates of up to 40% for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer have been reported based on radical cystectomy data.

- •

Absence of muscularis propria MP in the specimen leads to a significantly higher rate of understaging (60%–78%).

- •

Patients with high-grade (HG) Ta and HG T1 tumors, regardless of presence of muscle, are strongly encouraged to undergo a restaging transurethral resection (TUR).

- •

Repeat resection should be performed 2 to 6 weeks following initial TUR.

- •

Deep biopsies in the base and periphery of the old resection site should be performed.

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) comprised the vast majority of the estimated 73,510 new cases of bladder cancer diagnosed in the United States in 2012. Approximately 70% to 75% of patients with bladder cancer initially present at a low stage (stage 1), a category that includes carcinoma in situ (Tis – 1–10% alone as primary), tumors confined to the urothelial mucosa (Ta – 70%–80%), and those that invade only the underlying lamina propria (T1 – 20%). The prognosis for patients with NMIBC is generally good, with approximately 80% to 90% of patients alive at 5 years. In contrast, muscle-invasive bladder cancer, which represents about 25% of cases, has a significantly lower relative 5-year survival rate of 17% to 66% depending on tumor stage. Epidemiologic evidence demonstrates that these trends in incidence and survival for noninvasive and invasive bladder cancer have remained relatively stable since 1993. The most significant risk factor for bladder cancer is cigarette smoking. While the risk may decrease with smoking cessation, former smokers still have a higher risk of bladder cancer than never smokers. Additionally, in patients with NMIBC, current tobacco use and cumulative lifetime exposure are closely associated with recurrence and progression. There is no currently accepted genetic or inheritable cause of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, but studies suggest that polymorphisms in 2 carcinogen-detoxifying genes, GSTM-1 and NAT-2, may be responsible for increased susceptibility to developing bladder cancer in certain patients.

Who to restage

Understanding the Predictors of Understaging, Recurrence, and Progression

Patients with NMIBC represent a heterogeneous group and demonstrate a broad range of outcomes with respect to recurrence, progression, and survival. Accurate staging and a fundamental understanding of the pathologic findings that predict outcome are therefore of utmost importance in clinical management. Thus, when considering the value of restaging transurethral resection (TUR), the first question that must be addressed is “who?” That is, which patients may benefit from additional resection rather than proceeding to intravesical chemotherapy/surveillance cystoscopy? Importantly, restaging TUR, which assumes a complete initial TUR, is distinguished here from a repeat resection performed when a complete initial TUR cannot be accomplished.

Most (55%–75%) of Ta tumors are low grade (LG), and patients with high-grade (HG) tumors are at much greater risk of recurrence, progression, and death from bladder cancer compared with those with LG disease. Long term follow-up of Ta LG tumors demonstrates that the overall recurrence rate is 55%, with 6% and 20% experiencing progression of stage and/or grade, respectively. In contrast, 30% to 35% of Ta HG tumors will progress to at least T1 disease. Ta HG urothelial cancer is associated with a significant risk of progression and death as manifested by progression-free survival and disease-specific survival rates of 61% and 74%, respectively, according to 1 study. This has important implications when considering the merits of restaging TUR, since adequate tumor stage and grade information clearly guides future management decisions, including administration of intravesical therapy or a recommendation for early cystectomy in patients found to be understaged at initial TUR.

Along with Ta HG bladder cancer, carcinoma in situ (CIS) and T1 cancers are all considered high-risk NMIBC. Clinical stage T1 tumors, those invading beyond the mucosa but confined to the lamina propria at the time of TUR or biopsy, represent approximately 20% of NMIBC and behave more aggressively than Ta tumors. They may also be classified as HG or LG, but in contrast to stage Ta, most T1 tumors are HG and therefore have a high risk of progression. Within stage T1 urothelial cancer, studies have shown that deeper invasion into the lamina propria leads to higher progression rates (58%) compared with superficial invasion (36%), and depth of invasion (as measured by muscularis mucosae involvement) is a significant independent predictor of progression. While this is likely related in part to increased aggressiveness of more deeply invading tumors, this may also be indicative of the increased likelihood of an incomplete endoscopic resection in patients with tumors invading into the muscularis mucosae. Thus, adequate TUR is critical not only to ensure accurate staging and guide future management options, but also to remove all tumor from the bladder.

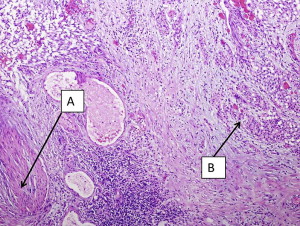

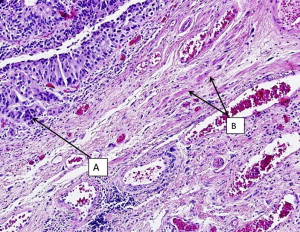

It should be emphasized that invasion of the muscularis mucosae is still considered non-muscle invasive disease in contrast to muscularis propria (MP) invasion, which is the hallmark of true muscle invasion (stage T2). Therefore, a TUR specimen with only muscularis mucosae and no MP is still considered inadequate for determination of muscle invasion. Fig. 1 demonstrates a cT1 tumor with MP present in the specimen and not involved by cancer. Fig. 2 demonstrates a cT1 tumor with only muscularis mucosae present in the specimen; it is therefore inadequate for the determination of muscle invasion due to lack of MP. The ability to distinguish between the MP and muscularis mucosae is challenging, however, as these images show. MP is a distinct layer of muscle fibers, whereas muscularis mucosae is typically a few smooth muscle cells arranged in fibers dispersed throughout the lamina propria.

Sylvester and colleagues reviewed 7 European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) trials in NMIBC and found that the probability of progression for T1HG disease ranged from 20% to 48% at 5 years, and the most important predictive factor was the presence of concomitant CIS. Patients who had T1 HG urothelial cancer without CIS had a 29% probability of progression at 5 years, whereas those with concomitant CIS had a 74% probability of progression at 5 years. Similarly, in a multivariate analysis of predictors of recurrence, progression, and survival in primary Ta and T1 urothelial cancer, Millan-Rodriguez and colleagues demonstrated that patients with CIS had almost twice the risk of recurrence and progression and 3 times the risk of mortality than those without CIS. CIS as a stand-alone entity is rare and represents only 1% to 10% of NMIBC. Additionally, although it is a noninvasive lesion, its presence is considered a strong indicator of risk for progression and HG disease. Patients with CIS in the primary TUR specimen in combination with Ta or T1 tumors should therefore be strongly considered to undergo restaging TUR for accurate staging and prognosis as they can potentially harbor more aggressive disease.

To better understand which patients require restaging TUR, factors besides grade, stage, and CIS need to be considered. Several studies have found that the number of prior recurrences, multiple tumors, large tumor size (>3 cm), and the presence of hydronephrosis are all predictors of recurrence and progression and are additional indicators of high-risk disease. In particular, tumor size and hydronephrosis are associated with muscle invasion and therefore often indicate tumor understaging in patients thought to have non-muscle invasive disease. Additional pathologic findings that are concerning for progression and highrisk of disease-specific mortality are micropapillary variants of urothelial carcinoma and lymphovascular invasion (LVI). The group at MD Anderson Cancer Center reviewed its experience with the micropapillary variant of urothelial carcinoma and found that in those who underwent intravesical bacillus calmette-guerin (BCG) therapy (all T1), only 19% (5/27) of patients were disease-free at a median follow-up of 30 months. Early cystectomy is typically strongly considered in these patients, and restaging TUR is imperative if a bladder preservation strategy is employed, in light of the high risk of progression. With respect to LVI, Cho and colleagues demonstrated that it was an independent predictor of recurrence and progression in 118 patients with NMIBC. Similarly, Resnick and colleagues demonstrated that patients with LVI at TUR were more likely to experience upstaging at the time of radical cystectomy. Finally, there may eventually be a role for molecular profiling to better define the need for restaging TUR. Known markers of disease progression include p53, p16, fibroblast growth factor 3 (FGFR3), E-cadherin, and urokinase-plasminogen activator. Future research may help to determine whether these markers can predict which patients may have occult invasive disease and more accurately stratify for risk patients with NMIBC after initial TUR.

In summary, given the data on upstaging, recurrence, and progression in patients with high-risk NMIBC, restaging TUR is indicated in any patient found to have high-grade and/or T1 disease but no MP in the specimen, unless radical cystectomy is planned. Both the 2007 American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines and the 2011 European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines for the management of NMIBC unequivocally recommend restaging TUR in this setting. The clinical relevance of this is apparent in light of contemporary reports revealing only 47% of patients with muscle present in the specimen on initial TUR. Whether restaging TUR is necessary in high-risk patients despite the presence of MP in the initial TUR specimen has historically been an area of debate. However, as will be discussed further, there is a substantial risk of upstaging even when MP is present in the initial TUR specimen, and therefore restaging TUR is increasingly considered standard of care in any patient with HG and/or T1 disease planning on proceeding with a bladder-sparing approach. According to the EAU guidelines, a second restaging TUR is recommended in any patient with HG and/or T1 bladder cancer on initial TUR, regardless of the presence of MP in the specimen (level of evidence 2a). The AUA guidelines also suggest that it is appropriate to consider restaging TUR in patients with HG T1 with MP and also HG Ta patients in an effort to improve the accuracy of clinical staging, although there is no explicit recommendation in favor of restaging TUR in these patients.

Who to restage

Understanding the Predictors of Understaging, Recurrence, and Progression

Patients with NMIBC represent a heterogeneous group and demonstrate a broad range of outcomes with respect to recurrence, progression, and survival. Accurate staging and a fundamental understanding of the pathologic findings that predict outcome are therefore of utmost importance in clinical management. Thus, when considering the value of restaging transurethral resection (TUR), the first question that must be addressed is “who?” That is, which patients may benefit from additional resection rather than proceeding to intravesical chemotherapy/surveillance cystoscopy? Importantly, restaging TUR, which assumes a complete initial TUR, is distinguished here from a repeat resection performed when a complete initial TUR cannot be accomplished.

Most (55%–75%) of Ta tumors are low grade (LG), and patients with high-grade (HG) tumors are at much greater risk of recurrence, progression, and death from bladder cancer compared with those with LG disease. Long term follow-up of Ta LG tumors demonstrates that the overall recurrence rate is 55%, with 6% and 20% experiencing progression of stage and/or grade, respectively. In contrast, 30% to 35% of Ta HG tumors will progress to at least T1 disease. Ta HG urothelial cancer is associated with a significant risk of progression and death as manifested by progression-free survival and disease-specific survival rates of 61% and 74%, respectively, according to 1 study. This has important implications when considering the merits of restaging TUR, since adequate tumor stage and grade information clearly guides future management decisions, including administration of intravesical therapy or a recommendation for early cystectomy in patients found to be understaged at initial TUR.

Along with Ta HG bladder cancer, carcinoma in situ (CIS) and T1 cancers are all considered high-risk NMIBC. Clinical stage T1 tumors, those invading beyond the mucosa but confined to the lamina propria at the time of TUR or biopsy, represent approximately 20% of NMIBC and behave more aggressively than Ta tumors. They may also be classified as HG or LG, but in contrast to stage Ta, most T1 tumors are HG and therefore have a high risk of progression. Within stage T1 urothelial cancer, studies have shown that deeper invasion into the lamina propria leads to higher progression rates (58%) compared with superficial invasion (36%), and depth of invasion (as measured by muscularis mucosae involvement) is a significant independent predictor of progression. While this is likely related in part to increased aggressiveness of more deeply invading tumors, this may also be indicative of the increased likelihood of an incomplete endoscopic resection in patients with tumors invading into the muscularis mucosae. Thus, adequate TUR is critical not only to ensure accurate staging and guide future management options, but also to remove all tumor from the bladder.

It should be emphasized that invasion of the muscularis mucosae is still considered non-muscle invasive disease in contrast to muscularis propria (MP) invasion, which is the hallmark of true muscle invasion (stage T2). Therefore, a TUR specimen with only muscularis mucosae and no MP is still considered inadequate for determination of muscle invasion. Fig. 1 demonstrates a cT1 tumor with MP present in the specimen and not involved by cancer. Fig. 2 demonstrates a cT1 tumor with only muscularis mucosae present in the specimen; it is therefore inadequate for the determination of muscle invasion due to lack of MP. The ability to distinguish between the MP and muscularis mucosae is challenging, however, as these images show. MP is a distinct layer of muscle fibers, whereas muscularis mucosae is typically a few smooth muscle cells arranged in fibers dispersed throughout the lamina propria.

Sylvester and colleagues reviewed 7 European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) trials in NMIBC and found that the probability of progression for T1HG disease ranged from 20% to 48% at 5 years, and the most important predictive factor was the presence of concomitant CIS. Patients who had T1 HG urothelial cancer without CIS had a 29% probability of progression at 5 years, whereas those with concomitant CIS had a 74% probability of progression at 5 years. Similarly, in a multivariate analysis of predictors of recurrence, progression, and survival in primary Ta and T1 urothelial cancer, Millan-Rodriguez and colleagues demonstrated that patients with CIS had almost twice the risk of recurrence and progression and 3 times the risk of mortality than those without CIS. CIS as a stand-alone entity is rare and represents only 1% to 10% of NMIBC. Additionally, although it is a noninvasive lesion, its presence is considered a strong indicator of risk for progression and HG disease. Patients with CIS in the primary TUR specimen in combination with Ta or T1 tumors should therefore be strongly considered to undergo restaging TUR for accurate staging and prognosis as they can potentially harbor more aggressive disease.

To better understand which patients require restaging TUR, factors besides grade, stage, and CIS need to be considered. Several studies have found that the number of prior recurrences, multiple tumors, large tumor size (>3 cm), and the presence of hydronephrosis are all predictors of recurrence and progression and are additional indicators of high-risk disease. In particular, tumor size and hydronephrosis are associated with muscle invasion and therefore often indicate tumor understaging in patients thought to have non-muscle invasive disease. Additional pathologic findings that are concerning for progression and highrisk of disease-specific mortality are micropapillary variants of urothelial carcinoma and lymphovascular invasion (LVI). The group at MD Anderson Cancer Center reviewed its experience with the micropapillary variant of urothelial carcinoma and found that in those who underwent intravesical bacillus calmette-guerin (BCG) therapy (all T1), only 19% (5/27) of patients were disease-free at a median follow-up of 30 months. Early cystectomy is typically strongly considered in these patients, and restaging TUR is imperative if a bladder preservation strategy is employed, in light of the high risk of progression. With respect to LVI, Cho and colleagues demonstrated that it was an independent predictor of recurrence and progression in 118 patients with NMIBC. Similarly, Resnick and colleagues demonstrated that patients with LVI at TUR were more likely to experience upstaging at the time of radical cystectomy. Finally, there may eventually be a role for molecular profiling to better define the need for restaging TUR. Known markers of disease progression include p53, p16, fibroblast growth factor 3 (FGFR3), E-cadherin, and urokinase-plasminogen activator. Future research may help to determine whether these markers can predict which patients may have occult invasive disease and more accurately stratify for risk patients with NMIBC after initial TUR.

In summary, given the data on upstaging, recurrence, and progression in patients with high-risk NMIBC, restaging TUR is indicated in any patient found to have high-grade and/or T1 disease but no MP in the specimen, unless radical cystectomy is planned. Both the 2007 American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines and the 2011 European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines for the management of NMIBC unequivocally recommend restaging TUR in this setting. The clinical relevance of this is apparent in light of contemporary reports revealing only 47% of patients with muscle present in the specimen on initial TUR. Whether restaging TUR is necessary in high-risk patients despite the presence of MP in the initial TUR specimen has historically been an area of debate. However, as will be discussed further, there is a substantial risk of upstaging even when MP is present in the initial TUR specimen, and therefore restaging TUR is increasingly considered standard of care in any patient with HG and/or T1 disease planning on proceeding with a bladder-sparing approach. According to the EAU guidelines, a second restaging TUR is recommended in any patient with HG and/or T1 bladder cancer on initial TUR, regardless of the presence of MP in the specimen (level of evidence 2a). The AUA guidelines also suggest that it is appropriate to consider restaging TUR in patients with HG T1 with MP and also HG Ta patients in an effort to improve the accuracy of clinical staging, although there is no explicit recommendation in favor of restaging TUR in these patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree