CHAPTER 35 Renal Transplantation

![]() Describe kidney stones following renal transplantation.

Describe kidney stones following renal transplantation.

Kidney stones following a renal transplant are an unusual complication. Stones may originate in the transplanted kidney following transplant secondary to any of the primary etiologies of kidney stones formation. Stones may also be transplanted with the stones having formed in the donor. Primary risk factors in the recipient include tertiary hyperparathyroidism, hypercalciuria, recurrent urinary tract infections, and urinary tract obstruction. Clinical presentation includes obstructive uropathy, hematuria, urinary tract infection, and allograft dysfunction. Renal colic is an unusual symptom in this population. Treatment can include observation and spontaneous passage of the stone, percutaneous or open nephrolithotomy, lithotripsy, cystoscopy, and ureteroscopy.

![]() What is a panel reactive antibody (PRA) and how are they usually formed?

What is a panel reactive antibody (PRA) and how are they usually formed?

PRA is a panel of common human leukocyte antigen (HLA) antigens against which potential kidney transplant recipients are tested. The degree of reactivity is a reflection of the presence of preformed antibodies in the recipient. Patients develop HLA antibodies through 3 primary processes: (1) exposure through previous transplant, (2) pregnancy, and (3) blood transfusions. A high degree of reactivity against the panel suggests that there will be difficulty in identifying a cross-match negative donor.

![]() How can HLA antibodies be removed or diminished?

How can HLA antibodies be removed or diminished?

HLA antibodies can be removed or depleted by the process of plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy and/or rituximab therapy. A combination appears to be most effective. The results are best with the blood group antibodies. The removal of HLA antibodies is more difficult and the results in this group suggest a higher risk of both cellular and antibody-mediated rejection and poorer long-term survival.

![]() Describe donor exchange programs.

Describe donor exchange programs.

The demand for organs for kidney transplantation has resulted in various exchange scenarios among incompatible donor recipient pairs. One such adaption has been the development of donor exchange programs. This program allows recipients with incompatible donors to exchange kidneys with other recipient donor pairs with similar incompatibilities. This exchange, which is frequently based on the blood group or cross-match incompatibilities, has increased the rate of transplant among these individuals. As more programs and patients enter into these exchanges the probability of finding compatible pairs increases. Paired donor exchange opportunities are currently being nationalized in the hopes of optimizing both transplant rates and the advantages of living donation.

![]() What is the average waiting time for a deceased donor transplant and what is the single most significant factor in determining how quickly a kidney may be available?

What is the average waiting time for a deceased donor transplant and what is the single most significant factor in determining how quickly a kidney may be available?

Depending on the geographical region and blood type, the average waiting time for cadaveric transplant can vary from 2 to 6 years. Blood type “O” recipients tend to wait the longest. Blood type “AB” recipients tend to have the shortest waiting time. Other issues such as antibodies, age, and obesity can further increase waiting. Living donation avoids many of these issues. Recipients of living donor transplants have the shortest waiting time.

![]() What are the leading causes of end-stage renal disease in the United States?

What are the leading causes of end-stage renal disease in the United States?

Diabetes is the single most common cause of renal failure. Other etiologies include hypertension, chronic glomerulonephritis, polycystic kidney disease, systemic lupus, interstitial nephritis, and various autoimmune nephritis syndromes.

![]() What is acute rejection, how is it diagnosed, and what is the current incidence?

What is acute rejection, how is it diagnosed, and what is the current incidence?

Acute cellular rejection is a T-cell–mediated rejection process and can occur at any time post-transplant. The diagnosis of acute rejection is most often made based on the findings of a rising serum creatinine and confirmed by transplant biopsy. Biopsies done for other reasons may also demonstrate rejection as well. Current maintenance immunosuppression is directed at the cellular rejection process. The incidence of acute rejection is currently 10% to 15%.

![]() What is the Banff system?

What is the Banff system?

The Banff system is a histologic standardized grading system for transplant rejection.

![]() What are the indications for native kidney nephrectomy?

What are the indications for native kidney nephrectomy?

The indications for native kidney nephrectomy prior to transplant or at the time of transplant are: (1) the presence of large symptomatic polycystic kidneys, (2) severe reflux associated with pyelonephritis, (3) severe uncontrollable hypertension, and (4) uncontrolled proteinuria.

![]() What causes hyperacute rejection and how can it be prevented?

What causes hyperacute rejection and how can it be prevented?

The presence of preformed antibodies at the time of transplant can result in an accelerated rapid antibody-mediated rejection. This process is B-cell mediated. Frequently, antibodies can be removed prior to transplantation via a process that involves plasmapheresis, IVIG, and rituximab either alone or in combination. Currently, antibody reduction among the ABO blood group discrepancies prior to transplant appears to be the most effective antidonor antibody group to treat. Acquired antibodies against the HLA antigen groups are much harder to reduce and tend to have lower graft survival rates.

![]() What is induction immunosuppression?

What is induction immunosuppression?

Induction agents are medications administered in the early or immediate postoperative period. These agents are potent immunosuppressants and are used to maximally suppress the immune response at the time of initial antigen exposure. Their effects can be long-lasting. These agents include both polyclonal antithymocyte and monoclonal (anti-IL-2 and anti-CD 52) agents. Induction therapy can be used in all patients or selectively. Induction therapy has increasingly been used in patients considered for maintenance immunosuppressive minimization. The use of induction therapy can be associated with a higher incidence of post-transplant infection and malignancy. These concerns weigh into the decision of when and how best to use these agents.

![]() What is maintenance immunosuppression?

What is maintenance immunosuppression?

Chronic maintenance immunosuppressive medication is used to prevent acute rejection. Various combinations are used, which most commonly include a calcineurin inhibitor, antimetabolites, and steroids. Other agents frequently used include m-TOR inhibitors and most recently the costimulator blocking agent. The use of these medications in various combinations allows minimization of potential side effects. The variety of combinations used reflects an overall dissatisfaction with the trade-off between immunosuppression and immunosuppressive complications.

![]() What medications are used to treat acute cellular rejection?

What medications are used to treat acute cellular rejection?

Acute cellular rejection is most commonly treated with high-dose steroids or antilymphocytic agents. Diagnosis of acute cellular rejection is made by finding an elevated creatinine and/or a suggestive biopsy. Treatment is generally successful especially when therapy is initiated early in the process. The success of treatment may best be determined by the established postrejection creatinine. The ability to return to baseline portends a better prognosis than a failure to do so.

![]() What is the overall graft survival for deceased and living donor transplants?

What is the overall graft survival for deceased and living donor transplants?

Many variables affect long-term graft survival. Better immunosuppression has improved early graft survival but has had minimal impact on long-term graft survival. Cadaveric kidney survival is also impacted by the type of organ utilized. A standard criteria donor (a donor between the ages of 10 and 50) versus donors at higher risk whose kidneys tend to show poorer long- and short-term graft function. These include expanded criteria donors (over the age of 50 years and other defined criteria), deceased cardiac donors, and prolonged ischemic times. Living donors tend to have much better results than cadaveric donors. Deceased donor kidneys have a 1-year graft survival of approximately 87%, a 3-year graft survival of approximately 76%, and a graft half-life of nearly 8 years. Living donors have a 1-year graft survival of 93%, a 3-year graft survival of approximately 86%, and a half-life of nearly 18 years.

![]() What is an expanded criteria donor (ECD) kidney?

What is an expanded criteria donor (ECD) kidney?

ECD kidneys refer to cadaveric kidney donors greater than 60 years of age or between the ages of 50 and 59 years and meet one of the following criteria: (1) hypertension, (2) creatinine greater than 1.5, or (3) death from a cerebral vascular accident. These kidneys are believed to have a higher risk of delayed function (acute tubular necrosis, ATN) and a higher risk of primary nonfunctioning. The half-life of these organs is believed to be shorter than standard criteria donor organs. Careful recipient selection is required and utilization of these organs in younger patients is generally avoided.

![]() What is a deceased cardiac donor (DCD)?

What is a deceased cardiac donor (DCD)?

A DCD organ donor is a donor who most frequently has experienced a devastating, irreversible neurologic injury, but fails to progress to brain death. The decision is made to withdraw life-support and after cardiac activity terminates the potential donor is pronounced dead. Donation can only proceed after pronouncement. Careful criteria for acceptability are applied as extensive ischemic injury can occur. There is a higher risk of delayed primary function and of primary nonfunction. As many of these donors are otherwise young and healthy, they are potential organs for younger carefully selected recipients. DCD organs have had a significant positive impact on the donor pool.

![]() What is a high-risk organ donor?

What is a high-risk organ donor?

The social and medical history, lifestyle choice, or social and medical risk factors of a donor increase the probability of disease transmission. Of particular concern is the transmission of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV. Potential donors are carefully screened for these diseases and all testing is negative, but there is a window period between exposure and conversion that must be considered. The degree of risk varies with the nature of the behavior. High-risk donors are defined using the same center for disease control (CDC) criteria as for blood donors. Risk of disease transmission must be taken into careful consideration. Full informed consent is required.

![]() What is a post-transplant lymphocele and how is it treated?

What is a post-transplant lymphocele and how is it treated?

A lymphocele is the most common perinephric fluid collection found in the post-transplant period. The etiology of lymphatic fluid can be either retroperitoneal recipient lymphatics or lymphatics associated with the transplant kidney itself. The incidence of post-transplant lymphocele is believed to be approximately 15%. The incidence has increased with modern immunosuppression. Most lymphoceles are asymptomatic and require no treatment. Symptoms when they occur typically are compressive in nature and are associated with allograft dysfunction and/or leg edema. The differential diagnosis includes urinoma and abscess. The diagnosis is made by ultrasound and percutaneous drainage and/or aspiration. Treatment with percutaneous drainage is successful approximately half the time. Intra-abdominal marsupialization, which can be performed either as an open or as a laparoscopic procedure, is successful more than 80% of the time.

![]() What is the significance of ATN in the transplant setting?

What is the significance of ATN in the transplant setting?

Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) is an ischemic injury to the kidney. This injury is often associated with both warm and cold ischemic times, donor age, cause of death, and an unfavorable recipient environment. ATN of the living donor kidney is relatively uncommon and is usually associated with surgical factors. ATN occurs in 20% to 40% of cadaveric donors. Clinically, ATN is defined as the need for dialysis in the early postoperative period. The more severe the ATN, the greater the risk of compromised long-term allograft function. The differential diagnosis includes vascular compromise, perinephric collections, hydronephrosis, acute cellular and antibody-mediated rejection, and drug toxicities. Diagnosis is supported by ultrasound findings and confirmed by biopsy. Treatment is supportive.

![]() What is post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD)

What is post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD)

PTLD is one of the most common post-transplant malignancies. Most cases of early PTLD are the result of infection with the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). Newly acquired or reactivated EBV infection can induce B-cell proliferation in the immunocompromised host. EBV-induced PTLD ranges from a polyclonal B-cell proliferation to a full-blown malignant monoclonal transformation. Diagnosis is frequently suggested by the findings of clinically significant adenopathy in the face of new or rising EBV titers and confirmed by biopsy. The initial step in the treatment of PTLD is the reduction or termination of immunosuppression. More aggressive disease may require the use of chemotherapy as well as immunosuppression withdrawal. CNS and bone marrow involvement suggest a poor prognosis.

EBV naïve patients receiving EBV positive donor organs are at greatest risk, particularly if exposed to lytic immunosuppressive agents.

![]() Describe the management of pregnancy in the kidney transplant patient. Which immunosuppressive agents are preferred or particularly toxic during pregnancy?

Describe the management of pregnancy in the kidney transplant patient. Which immunosuppressive agents are preferred or particularly toxic during pregnancy?

Uremic infertility is rapidly corrected by successful renal transplantation, and pregnancy becomes a significant possibility. Patients are advised to take precautions to avoid pregnancy until allograft function has stabilized and immunosuppressive medications can be adjusted and overall risk reduced. If pregnancy occurs, careful management by a high-risk obstetrician/perinatologist is advisable. Pregnancy post-renal transplant, if carefully planned and monitored, is often a successful and rewarding experience. Immunotherapy may need to be adjusted to avoid agents with significant teratogenic potential. Immunosuppressants such as Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and the m-TOR inhibitors have been shown to be particularly toxic to fetal development. Calcineurin inhibitor agents have been used with minimal risk. Azathioprine and steroids may in fact be the safest options.

![]() How do calcineurin inhibitors work?

How do calcineurin inhibitors work?

Cyclosporine and tacrolimus are calcineurin inhibitors frequently used in maintenance immunosuppression. These agents bind to a class of immunophilins in the cytosol of T helper cells. This complex binds to calcineurin. This immunophilins–calcineurin complex blocks the signaling pathway, which results in upregulation of IL-2 cell surface receptors. By blocking T-cell proliferation, these medications exert their primary immunosuppressive effect. Various formulations of these medications currently exist. Drug monitoring is critical to the safe and effective management of these medications. Toxicities of this class of medications include lowering of the seizure threshold, nephrotoxicity, hyperkalemia, hyperglycemia, and dermatologic changes. Multiple drug interactions are also possible.

![]() How does MMF work?

How does MMF work?

MMF is the prodrug of mycophenolic acid. As an antimetabolite, the drug binds to inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase preventing proliferation of T and B cells. Drug level monitoring is possible, but appears to be of limited benefit. Primary side effects of this medication include gastrointestinal (GI) disturbances (nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea), myelosuppression, and leukopenia. Several birth defects have been associated with the use of MMF during pregnancy.

![]() How do m-TOR inhibitors work?

How do m-TOR inhibitors work?

Currently, there are 2 primary formulations of this medication: sirolimus and everolimus. This drug acts in the cytosol of T cells by binding with a specific class of immunophilins and inhibits cellular proliferation signals. These agents have less nephrotoxicity compared to the calcineurin inhibitors and may have antitumor properties. Toxicities are often significant and include hyperlipidemia, pneumonitis, proteinurea, peripheral edema, leukopenia, mouth ulcers, and poor wound healing. Drug level monitoring is helpful, and these medications are often used in conjunction with the calcineurin inhibitors. Fear of complications and a lack of superior long-term allograft outcomes have limited the general use of this class of medications. This medication class is most often used selectively. It is often recommended that m-TOR inhibitors be stopped prior to major surgical intervention because of their negative impact on wound healing.

![]() Describe the failed renal allograft.

Describe the failed renal allograft.

The best management of the failed renal allograft has not been defined. Concerns regarding the potential complications of a surgical procedure, the risk of ongoing immunosuppression, the risk of chronic ongoing inflammatory response, and the risk of developing HLA antibodies all weigh into the clinical decision-making process. Currently many centers use a selective approach with nephrectomy reserved for patients with symptomatic graft failure and graft loss due to early immunologic or technical graft issues. Decisions regarding withdrawal of immunosuppression in failed allografts that remain in place vary from center to center. Some choose to maintain a low level of reduced immunosuppressive medications. Some will taper all immunosuppressive medications. Following nephrectomy, immunosuppressive therapy can be stopped.

![]() What is the pretransplant management of hyperoxaluria and renal failure?

What is the pretransplant management of hyperoxaluria and renal failure?

Primary oxalosis (Type 1 and 2) results from a hepatic enzymatic defect, which causes increased serum oxalate levels and the deposition of calcium oxalate in the tissues. The enzymatic defect is transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait. Secondary oxalosis is the result of other disease processes and does not have a genetic component. In secondary oxalosis treatment of the underlying process is indicated. The deposition of calcium oxalate level occurs in all tissues and can lead to renal failure. The treatment of hyperoxaluria depends on the underlying etiology. In renal failure, intensive dialysis therapy can decrease a patient’s oxalate load to a level at which tissue deposition does not occur—less than 50 mg/mL. Patients with primary oxalosis are best managed with early combined or staged liver–kidney transplant.

![]() What are the complications of bladder drainage of pancreatic exocrine secretions in kidney–pancreas transplantations?

What are the complications of bladder drainage of pancreatic exocrine secretions in kidney–pancreas transplantations?

There are many technical variations for pancreas transplantation. The drainage of pancreatic exocrine secretions by the anastomosis of the duodenal segment of the allograft to the bladder was a major technical advancement in the clinical evolution of the procedure. Nowadays this anastomosis is most frequently replaced by an enteric one. This change was a result of the frequent complications associated with bladder drainage. These complications are: (1) metabolic acidosis secondary to the significant loss of sodium bicarbonate and fluid comprising pancreatic exocrine juices, (2) graft pancreatitis associated with a neurogenic bladder and reflux of bladder contents into the transplanted duodenal segment, (3) frequent urinary tract infections associated with an alkaline urine and a neurogenic bladder, and (4) cystitis/urethritis associated with mucosal exposure to the activated pancreatic enzymes. The severity of symptoms dictated the need for conversion to an enteric drainage and could be required in 15% to 20% of cases.

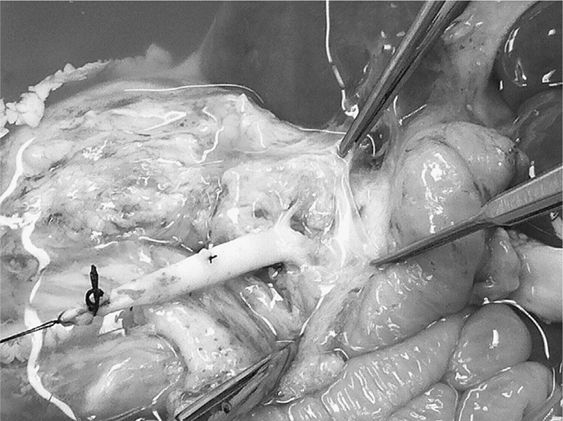

![]() Describe renal transplantation in the face of a dysfunctional bladder.

Describe renal transplantation in the face of a dysfunctional bladder.

A significant number of patients present for renal transplantation with a history of poor bladder emptying, frequent urinary tract infections (UTIs), incontinence, or other bladder abnormalities. In the face of such a history a thorough urologic evaluation is required. Preoperative definition and preparation for the management of these problems can have a significant impact on the success of the transplant.

![]() Describe the management of renal artery stenosis.

Describe the management of renal artery stenosis.

Renal artery stenosis is one of the more common vascular complications of renal transplantation. Lesions may be asymptomatic or may present with hypertension, fluid retention, worsening renal function, or congestive heart failure. An abdominal bruit over the allograft may or may not be present. Pathogenic processes involved include immunologic, infectious, and/or progressive atherosclerotic disease. The diagnosis is frequently made by the findings of elevated systolic velocities on duplex renal ultrasound and can be confirmed by either MRA or angiography. The primary therapy for significant disease is percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA). Surgical correction is complex and generally reserved for cases not amendable to PTA.

![]() 10 days after transplant a patient develops drainage from the wound. An ultrasound demonstrates hydronephrosis and a perinephric collection. Drainage of the collection demonstrates sterile fluid with a fluid creatinine of 38 mg/dL. A nephrostomy is performed and demonstrates a leak at the ureteroneocystostomy. How should this be treated?

10 days after transplant a patient develops drainage from the wound. An ultrasound demonstrates hydronephrosis and a perinephric collection. Drainage of the collection demonstrates sterile fluid with a fluid creatinine of 38 mg/dL. A nephrostomy is performed and demonstrates a leak at the ureteroneocystostomy. How should this be treated?

Currently the instance of ureteral complications post-renal transplant is approximately 2%. Ureteral obstruction/stricture is the most common post-transplant ureteral complication and urine leak the least common. Most urine leaks occur at the ureteroneocystostomy and are technical in nature. Factors such as ischemia and urinary retention can play a significant role. Small urine leaks can often be managed by placement of a Foley catheter with or without nephrostomy and stenting. Large leaks may best be dealt with direct surgical repair, frequently involving revision of the ureteroneocystostomy, pyeloureterostomy, or pylocystostomy. Revisions and repairs are most commonly done over a stent. Routine stenting at the time of transplant remains a subject of debate. In the above case, a ureteral stent was positioned and a Foley catheter was placed. A nephrostogram 6 weeks later confirms no further leak or stricture.

![]() What are the indications for native nephrectomy?

What are the indications for native nephrectomy?

The indications for nephrectomy prior to renal transplant include (1) chronic infections, (2) heavy proteinuria, (3) intractable hypertension, and (4) symptomatic polycystic kidney disease. Native nephrectomy is infrequently required and can be performed prior to or at the time of transplant.

![]() Describe chronic allograft nephropathy (CAN).

Describe chronic allograft nephropathy (CAN).

CAN is a histologic diagnosis of varying severity with findings of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. Patients may be asymptomatic or have evidence of progressive deterioration of allograft function. Multiple etiologies have been associated with CAN and include chronic ongoing immunologic injury either of a cellular or antibody-mediated process, evolving ischemic/traumatic injury, and chronic medication exposure particularly to calcineurin inhibitors.

![]() What is cellular rejection?

What is cellular rejection?

Cellular rejection is a T-cell–mediated process. Antigen-presenting cells present antigen to the T-cell antigen receptor. This interaction in conjunction with various costimulators can activate a T-cell response characterized by clonal expansion and the upregulation of various cell surface proteins. This activation results in the infiltration of the allograft by activated T cells, an associated inflammatory response, cellular injury, and death. Current maintenance and induction immunosuppression is designed to block T-cell activation and interfere with the interaction between the donor antigen and recipient T-cell. The incidence of acute rejection under current immunosuppression protocols is 10% to 20%.

![]() Describe post-transplant cytomegalovirus infection (CMV).

Describe post-transplant cytomegalovirus infection (CMV).

CMV can be transplanted from the donor or reactivated in the recipient following kidney transplant. CMV disease is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in the recipient. Antiviral agents are available for prophylaxis and treatment. Those at highest risk for CMV infection are recipients without previous CMV exposure who receive a kidney from a CMV positive donor. These patients frequently receive CMV antiviral prophylaxis in the first several months post-transplant. Those at the lowest risk for CMV infection are CMV naïve recipients who receive kidneys from CMV naïve donors. Prophylaxis is not usually given in this circumstance. Clinically CMV infection presents as an asymptomatic viremia or presents as a syndrome of fever, leukopenia, and allograft dysfunction. CMV gastritis and colitis are also common presentation. Active disease may require a reduction in immunosuppression.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree