- Kidney transplantation is generally the optimal form of renal replacement therapy (RRT) in terms of patient survival, quality of life and cost-effectiveness.

- Immunosuppressive treatment is necessary for the life of the kidney transplant—hence compliance is a major issue in the graft survival.

- (Blood group) ABO compatibility is desirable between the donor and recipient. The risk of transplant rejection is less where there is good human leukocyte antigen (HLA) antigen ‘match’. Blood transfusions can sensitize the recipient to potential donor HLA antigens, and so should be avoided if possible when there is a likelihood of transplantation.

- A live, unrelated transplant with complete HLA mismatching has a better long-term outcome than a cadaveric organ with no mismatch at all.

- Living donors now account for > 25% of all kidneys transplanted in the United Kingdom, and this is increasing.

- Post-operatively, most kidneys function immediately. Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) is the single most likely cause of delayed graft function, and is usually reversible.

- The main complications of kidney transplantation are:

- Rejection: 10–30% of transplanted kidneys are acutely rejected; this presents as a decline in renal function usually within the first three months. Hyperacute rejection, which occurs within hours, is very rare.

- Tubulo-interstital fibrosis, scarring, sclerosis and vasculopathy: this is the main cause of graft failure; progressive and irreversible increases in creatinine, associated with proteinuria, usually occur over years.

- Infection: the main concern is susceptibility to opportunistic infections, notably Cytomegalovirus and Pneumocystis carinii.

- Malignancy: increased risk of post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorders associated with Epstein–Barr virus infection.

- Recurrence: all forms of glomerulonephritis can recur and affect the transplanted kidney.

- Rejection: 10–30% of transplanted kidneys are acutely rejected; this presents as a decline in renal function usually within the first three months. Hyperacute rejection, which occurs within hours, is very rare.

- Graft survival at one year is now approximately 90–95% for cadaveric kidneys and more than 95% for kidneys from living donors. Overall, graft survival is about 50% at 10 years; the main causes of graft attrition are either tubulo-interstital fibrosis, scarring, sclerosis and vasculopathy or death of the patient.

Introduction

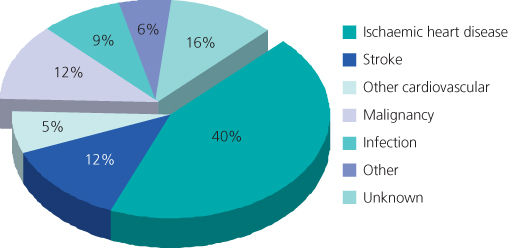

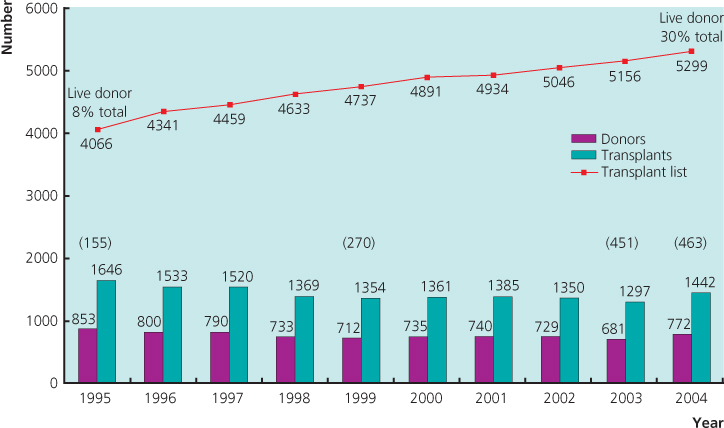

Kidney transplantation is the optimal form of renal replacement therapy (RRT), whether in terms of patient survival, quality of life or cost-effectiveness. However, this option is available to only about 30% of RRT patients. The number of patients on the waiting list is increasing as transplantation is now a well-established procedure (Figure 11.1), immunosuppression regimes are continually refined and previously contraindicated recipients are now included (e.g. HIV-positive patients). Equally, tissue-typing and blood group incompatibilities are now more easily circumvented, and there has been a significant change in the type of kidney donations now accepted, for example altruistic.

Figure 11.1 Cadaveric kidney programme in the United Kingdom, 1995–2004. Number of donors, transplants and patients on the active transplant list at 31 December each year (live donors indicated in parentheses).

(Source: Figures from United Kingdom Transplant (UKT)

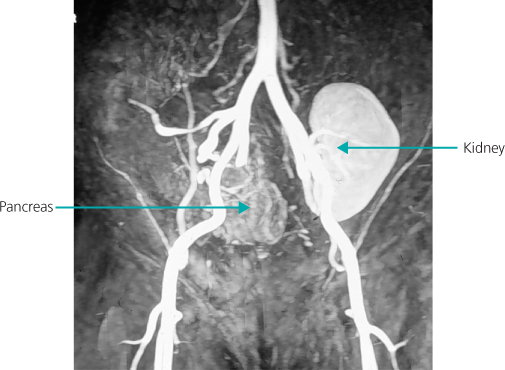

As well as kidney transplantation alone, kidneys can be transplanted at the same time as a liver (e.g. cirrhosis with kidney failure, or primary hyperoxaluria) or a heart. Simultaneous kidney–pancreas transplantation is less common, but a significant treatment option for type 1 diabetic patients with end stage renal failure (ESRF) (Figure 11.2). Space considerations preclude more detailed descriptions.

Figure 11.2 Magnetic resonance angiogram showing a kidney transplant on the right and a pancreas transplant on the left of the figure.

Immunological Aspects of Transplantation

The almost universal need to continue immunosuppressive treatment for the life of the kidney transplant for all donor/recipient combinations means that compliance is a major issue in graft survival.

Acquired immunity consists of the cellular (T-cell mediated) and humoral (B-cell mediated) responses, and both are involved in graft rejection. Essentially, the acquired immune response depends on recognition of graft antigens as being foreign and this stimulates various effector mechanisms against the graft, such as macrophage activation, natural killer cell response, delayed hypersensitivity, cellular cytotoxicity, plus complement fixation.

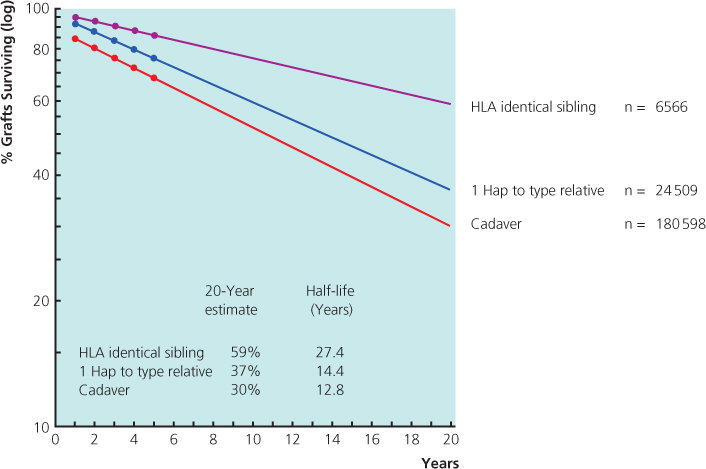

Figures 11.3 and 11.4 detail the immunological barriers to transplantation, and ‘matching’—the extreme polymorphism of alleles at the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci mean that a degree of mismatch is likely between donor and recipient, and this is usually expressed as a mismatch score, i.e. 0–0–0 being a perfect match and 2–2–2 being a complete mismatch.

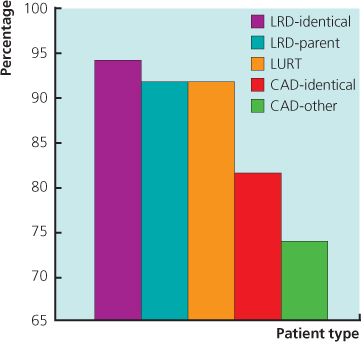

Figure 11.3 Relationship between survival and type of donor (first kidney transplants 1985–2004). (CTS-K-1503-0206).

Figure 11.4 Three-year renal graft survival. UCLA data 28 945 patients. The outcome of HLA-identical cadaveric kidneys is inferior to all categories of live donor, including living unrelated transplants. CAD: cadaveric donor; LRD: living-related donor; LURD: living unrelated donor.

(Source: Terasaki PI et al. (1995) High survival rates of kidney transplants from spousal and living unrelated donors. New Engl J Medi 333(6): 333–6

The Kidney Donor

There are two broad categories: cadaveric or living. Cadaveric donors are either heart-beating or non-heart-beating donors (NHBDs). Table 11.1 shows contraindications to cadaveric kidney donation. There were over 18.5 million people on the UK Organ Donor Register in January 2012.

Table 11.1 Contraindications to cadaveric donation

| Absolute | Relative |

| Chronic renal disease | Age < 5 or > 60 |

| Potentially metastasizing malignancy | Mild hypertension |

| Severe hypertension | Treated infection |

| Bacterial septicaemia | Nonoliguric acute tubular necrosis |

| Current intravenous drug user | Positive hepatitis B and C serology |

| HIV positive | Intestinal perforation with spillage |

| Warm ischaemia > 45 min | Prolonged cold ischaemia |

| Irreversible acute kidney injury | High-risk behaviour |

Cadaveric

The largest group of transplants comes from brain-stem dead patients with maintained cardiac output, usually in an intensive therapy unit (ITU) setting. Cause of death is usually intracranial haemorrhage or trauma. Kidneys from NHBDs, i.e. post-circulatory arrest, have shown comparable rates of success. However, the drawback to this approach is the warm ischaemic time (the time between cessation of heartbeat with the diagnosis of death and cooling of the organ). Of all potential donors in the ITU setting, consent for donation is not forthcoming from 36% of families.

Once a donor is identified, HLA typing is carried out and the most suitable recipient found through a national matching scheme administered by the NHS Blood and Transplant Authority (see website in Further reading). Clinically, peri-retrieval factors such as haemodynamic instability, ventilation, hypothermia and diabetes insipidus are managed to optimize perfusion.

Living

This now accounts for 25–30% of all kidneys transplanted in the United Kingdom (Figure 11.1), and in some Scandinavian and American centres live transplants are more numerous than deceased donor options. Living donation is on the increase in the United Kingdom—it may become the most practical way to address the donor organ deficit for kidneys at least, especially as live-unrelated donation (e.g. between spouses or altruistic) is yielding excellent outcomes and newer surgical techniques are being employed with the benefits of reduced pain, greater cosmesis and faster postoperative recovery (e.g. laparoscopic nephrectomy). A live-unrelated transplant with complete HLA mismatching still has a better long-term outcome than a cadaveric organ with no mismatch at all (Figure 11.3). Another advantage of living donors is the possibility of considering a ‘marginal’ recipient who may not be suitable for a cadaveric kidney.

The process of evaluation of the living donor is outlined fully in the Living Donor Guidelines, as set by the British Transplant Society and UK Renal Association. Patients and potential donors are given information leaflets and videos, and donors undergo a full series of screening investigations. Those who go on to donate have a risk of death of 1 in 3000, and there is no excess risk of hypertension or ESRF post-donation. Regardless, monitoring of blood pressure, urinary protein excretion and renal function in the longer term in kidney donors are important. However, the final donation rate may be as low as 20–25% in all those who are assessed as potential live donors. The reasons for this vary from immunological (40%) and medical (20%), to donor withdrawal or uncertainty (up to 40%). All potential living donors (whether related or unrelated) are assessed independently at a local level to determine their suitability for donation under terms set out by the Human Tissue Act 2004. More complex cases can be referred to the Human Tissue Authority. See http://www.uktransplant.org.uk/ukt/how_to_become_a_donor/living_kidney_donation/questions_and_answers.jsp.

Recipient

Kidney transplantation is considered suitable for patients with chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis or predicted to require dialysis within 6 to 12 months. In the United Kingdom, around 25% of such patients are transplanted, the main constraint being donor supply. The main principles to consider during recipient selection are:

- the benefits in terms of quality and duration of life should outweigh the risks to the patient in terms of the procedure and subsequent immunosuppression, especially in patients with other comorbidities or older patients;

- with cadaveric organs, justifying the use of a limited resource and allocation should be in terms of maximum benefit to society (patients not likely to survive five years or less should not receive a cadaveric donor kidney);

- in living donors, the risk to the donor should be justified by the predicted benefit of a successful transplant.

Apart from these general issues and those pertaining to the undertaking of major surgical intervention in the context of renal disease, various specific clinical factors must be considered.

Infection

Active infections should be eradicated where possible (e.g. tuberculosis); patients with chronic hepatitis B or C can prove challenging, as post-transplantation exacerbation of virally driven liver pathology is well recognized. Patients with recurrent urinary tract infection are considered for native nephrectomy. Those at risk of post-transplant tuberculosis (TB) should have TB prophylaxis post-operatively.

Malignancy

Patients with current malignancy are not considered for transplantation, but treated patients may be transplanted after a recurrence-free period, depending on type of malignancy.

Cardiovascular Disease

As this is the most common cause of death (and hence graft loss) post-transplant (Figure 11.5), any history or evidence of disease is thoroughly investigated and treated as appropriate. In addition, certain groups of asymptomatic patients, such as those aged over 50 years, smokers and all diabetics, should undergo cardiovascular screening (e.g. stress echocardiography, nuclear scintigraphy, coronary angiography, iliac arterial imaging).

Figure 11.5 Cardiovascular disease is the major cause of death with a functioning graft in renal transplant recipients. First grafts 1984–1996 92 deaths in 1260 patients.

(Source: Kavanagh D et al. (1999) Electrocardiogram and outcome following renal transplantation. Nephron 81(1): 109–10