, Mark Thomas1 and David Milford2

(1)

Department of Renal Medicine, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham, UK

(2)

Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham, UK

Abstract

In this chapter we explain:

How to assess an arteriovenous fistula

Peritoneal dialysis catheter problems

Fluid overload and volume assessment in a dialysis patient

Causes of a decline in kidney transplant function

How infections change with time after transplantation

Malignant disease related to immunosuppression

There are three types of renal replacement therapy – haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis and a kidney transplant. In this chapter, we explain some clinical aspects of these treatments that may be encountered by a non-specialist doctor, either incidentally when seeing the patient for another problem or in the emergency department.

Haemodialysis

Haemodialysis involves removing blood from the body and passing it though an artificial kidney. This ‘dialyser’ contains thousands of semi-permeable hollow fibres. Blood flows through the fibres and back to the patient while dialysis fluid flows around the fibres in the opposite direction. Diffusion and ultrafiltration occur across the fibre membrane to remove waste products and excess fluid and correct electrolyte abnormalities. Adequate dialysis is typically achieved by having three treatments per week, each four hours long every week.

Vascular Access

Vascular access, which enables blood to be passed through the dialyser, is a crucial issue in haemodialysis. The ideal method is to insert a large needle into an arteriovenous (AV) fistula or graft. Second best is to insert a catheter into a large vein.

An AV fistula is created by joining an artery to an adjacent vein (Fig. 18.1). Strictly speaking, the fistula is the anastamosis but the word is used to refer to the enlarged vein. If an anastomosis is not feasible, a piece of artificial vessel – a graft – may be inserted between the artery and vein.

Fig. 18.1

The anatomy of an arteriovenous fistula (AVF). The ideal site for the anastomosis is between the radial artery and the cephalic vein near the wrist, as shown here. Blood returns up the vein rather than continuing into the hand. Perfusion of the hand is normally maintained by flow in the deep palmar arch via a branch from the ulnar artery. Other options for an anastamosis are between the brachial artery and the cephalic vein and between the brachial artery and the basilic vein

The increased pressure in the vein causes it to enlarge and develop thickened walls. Over time and with repeated needling, the fistula vein can become massively enlarged.

The main problems that arise with an AV fistula are [1]:

Infection – cellulitis or superficial pustules

Steal syndrome – reduced perfusion of the distal part of a limb when collateral flow to the extremity cannot compensate for blood diverted to the fistula (Fig. 18.2)

Fig. 18.2

Ischaemia of the thumb, index and middle fingers caused by the ‘stealing’ of blood fromthe radial side of thehand by a radio-cephalic arteriovenous fistula. Flow from the ulnar artery into the deep palmar archwas restricted by atherosclerotic disease. The red wristband warns against venepunctureand blood pressure measurement in the fistula arm

Ischaemic painful polyneuropathy – commoner with an upper arm fistula and in patients with diabetes or vascular disease

High output cardiac failure – uncommon but may require the fistula to be tied off

Clotting – usually due to slow flow caused by a stenosis in the fistula vein; requires urgent specialist attention to increase the chances that the fistula can be salvaged

Stenosis and aneurysm – often occur together, the aneurysm forming upstream of a stenosis. A rapidly growing aneurysm covered with thin or dusky skin may rupture and requires urgent specialist attention

Clinical evaluation of a fistula can identify the site of a stenosis. The commonest site is near the anastamosis because the surgical wound stimulates fibrosis in the vein. The stenosis reduces the flow into the fistula, weakening the thrill that can be felt and the bruit that can be heard.

Stenosis in the vein downstream of the fistula increases the pressure in the fistula. Normal fistula pressure is about 35 mmHg; if there is a stenosis, the pressure may be over 100 mmHg. This can be detected by elevating the arm. When the arm is above the head, blood should drain into the right atrium with little resistance to flow and the fistula should collapse. If there is a central stenosis, the fistula vein does not collapse and feels hard and pulsatile (Fig. 18.3).

Fig. 18.3

This large radiocephalic fistula is shown with the arm dependent (left) and then elevated (right). On elevation, the fistula collapses completely except for two distended sections where the vessel wall has been weakened by repeated needling. These were soft, indicating that there was no stenosis obstructing flow. The dilated section near the scar caused by the anastamosis operation showed an arterial pulse wave transmitted from the radial artery. For a video of this examination go to vimeo.com/123945414

During dialysis, blood is pumped through the artificial kidney at speeds of about 300 ml/min. If there is a stenosis in the vein downstream of the fistula, blood pumped back into the fistula cannot all escape up the arm. Instead some recirculates round and round the dialysis circuit (Patient 18.1). The patient appears to be dialysing normally but potassium, urea and other toxins are not cleared [2]. The patient may present later as an emergency with a dangerously high serum potassium concentration. Urgent radiological imaging and intervention are needed to dilate the vein, prevent the fistula clotting and restore effective clearance on dialysis.

Patient 18.1: Recirculation Due to Arteriovenous Fistula Stenosis

The dialysis nurses were increasingly concerned about Mr. Trellis’ fistula. The blood flow rate during dialysis was normal but the post-dialysis urea and potassium concentrations were 28 and 5.2 mmol/L (BUN = 78 mg/dL, K+ = 5.2 mEq/L) compared to the usual 15 and 3.5 (42 mg/dL, 3.5 mEq/L) respectively. The monitor of recirculation built into the dialysis machine suggested that the percentage of blood recirculating had increased. An urgent fistulagram was performed (Fig. 18.4).

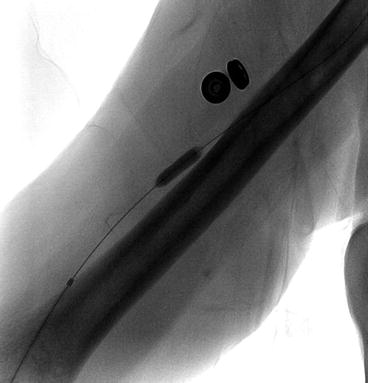

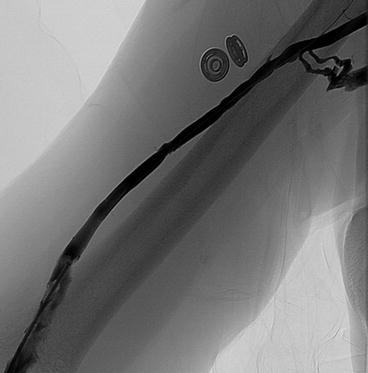

Fig. 18.4

A fistulagram study of the vein draining blood downstream from an arteriovenous fistula. The catheter can be seen in the fistula (white arrow). There is a tight stenosis in the cephalic vein (black arrow) related to a venous valve. The round objects next to the vein are fasteners on the patient’s gown

The stenosis restricts the return of blood up the fistula towards the heart. During dialysis, a proportion of the blood flowing from the venous needle flows back to the arterial needle, recirculating around the dialyser (Fig. 18.5).

Fig. 18.5

Recirculation in the dialyser circuit. Blood is removed from the fistula vein via the arterial needle, pumped through the dialyser by the dialysis machine and returned to the fistula via the venous needle. The high resistance to flow up the fistula forces some of the returned blood back towards the arterial needle. It then flows round the dialyser circuit again

Complications of a Haemodialysis Catheter

The main complications of a haemodialysis catheter are infection, clotting and venous stenosis. Infection tends to track down the catheter from the exit site to form a biofilm around the catheter. This can lead to septicaemia, endocarditis and more distant seeding of infection such as osteomyelitis. Because of the serious consequences of infection, a dialysis catheter should not be used for any purpose other than dialysis.

Clotting of the catheter is detected when dialysis is attempted. Blood cannot be withdrawn if a clot or stenosis of the surrounding central vein obstructs flow.

If a catheter is in place for a prolonged period, stenosis and eventual occlusion of a central vein may occur. If an arteriovenous fistula is then created on the same side, the increase in venous pressure causes dilatation of veins over the upper chest and neck (Fig. 18.8).

Fig. 18.8

Dilated veins across the right upper chest and neck of a lady due to occlusion of the right brachial vein in the axilla caused by a previous dialysis catheter. Venous blood flow is increased by an arteriovenous fistula in the right upper arm, covered with dressings. There are scars from a previous catheter and fistula surgery on her chest and left arm

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree