Renal Masses

Lisa M. Zorn MD

Stuart G. Silverman MD

Case 7-1

History: 33-year-old female with a history of nephrolithiasis and left flank pain.

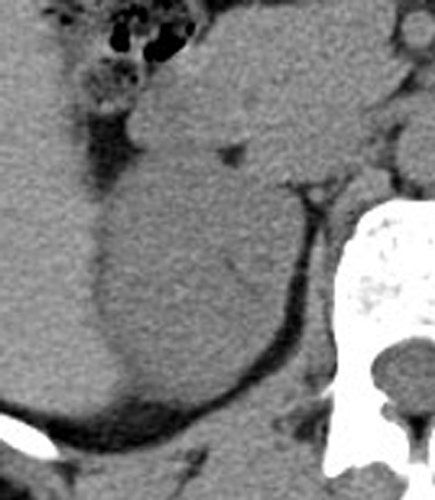

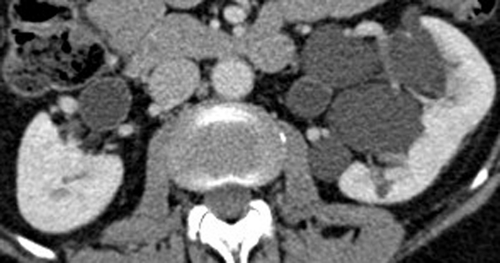

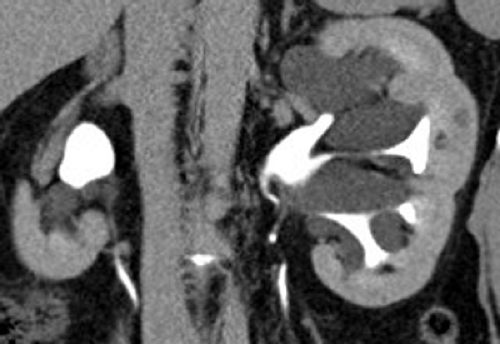

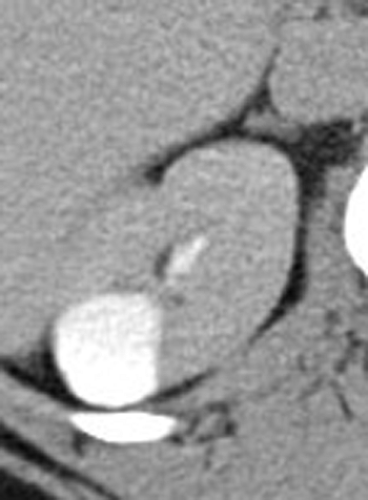

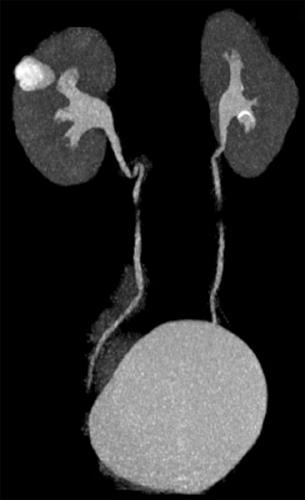

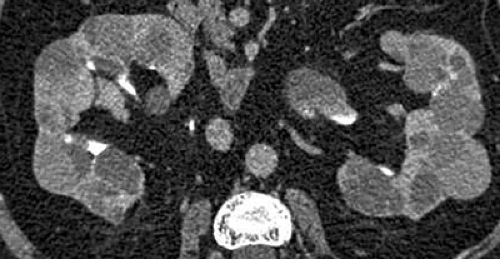

Findings: Axial unenhanced (A) and nephrographic (B) images from a CT urogram demonstrate a 2.5 × 1.6 × 1.5 cm, low-attenuation cystic mass with lobulated margins in the upper pole of the right kidney. Nephrographic phase image (B) demonstrates thin septations and an enhancing outer wall (arrow). Axial image in the excretory phase (C) shows that the lesion fills with contrast material (arrow). Coronal image (D) demonstrates multiple areas of focal parenchymal scarring (arrow) at the superior and inferior poles of both kidneys along with caliectasis.

Diagnosis: Reflux nephropathy

Discussion: The process of progressive renal injury with associated reflux of infected urine is called reflux

nephropathy (see Cases 6-10 and 8-2). Intrarenal reflux of infected urine damages the affected renal lobe, resulting in caliectasis and associated parenchymal scarring. Reflux nephropathy affects the polar regions of the kidneys prefer-entially. CT urography was helpful in this case by providing excretory phase images and coronal displays. The upper pole abnormality may have been mistaken for a cystic neoplasm if the excretory phase was not included. Coronal displays are valuable in noting that the poles are affected prefer-entially. Also, coronal images can be used to confirm that the caliectasis is associated with renal scarring.

nephropathy (see Cases 6-10 and 8-2). Intrarenal reflux of infected urine damages the affected renal lobe, resulting in caliectasis and associated parenchymal scarring. Reflux nephropathy affects the polar regions of the kidneys prefer-entially. CT urography was helpful in this case by providing excretory phase images and coronal displays. The upper pole abnormality may have been mistaken for a cystic neoplasm if the excretory phase was not included. Coronal displays are valuable in noting that the poles are affected prefer-entially. Also, coronal images can be used to confirm that the caliectasis is associated with renal scarring.

Case 7-2

History: 67-year-old female with hydronephrosis.

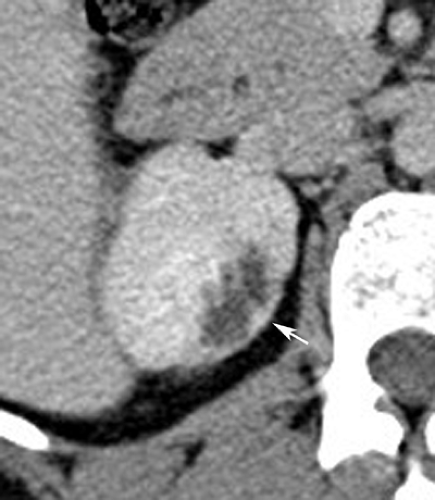

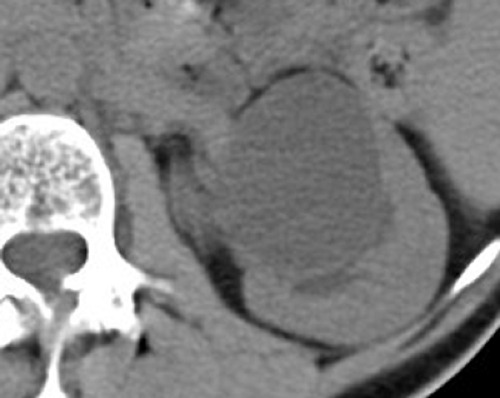

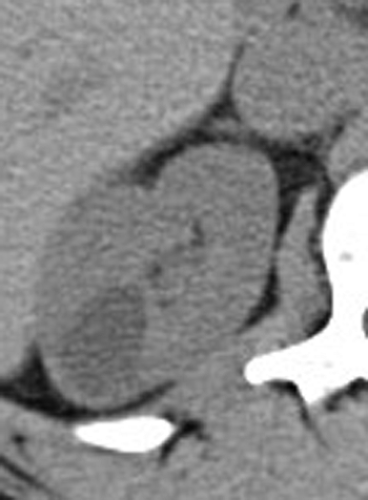

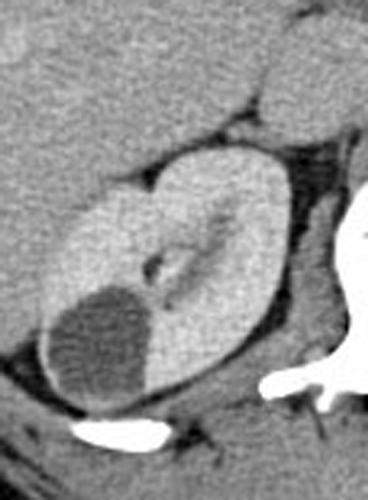

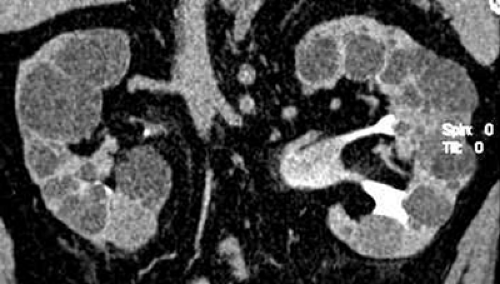

Findings: Axial unenhanced (A), nephrographic (B), and excretory phase (C) images and coronal excretory phase (D) images from a CT urogram demonstrate a homogeneous, low-attenuation, 4-cm mass in the upper pole of the right kidney. The mass has a smooth, thin wall, contains no septations or calcifications, and does not enhance.

Diagnosis: Simple renal cyst

Discussion: Simple renal cyst is the most common renal mass and is thought to arise from tubular obstruction, renal vascular compromise, or medullary interstitial fibrosis. They are found in half the population older than age 50 years. Simple cysts are often multiple and bilateral. Small cysts are almost always asymptomatic. Large cysts may cause obstruction, pain, hematuria, or hypertension. In order to be diagnosed as a simple cyst, a mass should be well-marginated, low attenuation (<20 HU), contain no septations or calcifications, and be nonenhancing (i.e., the mass should not enhance by more than 10 HU after contrast material administration). Simple renal cysts are classified by Bosniak as category I cysts and can be diagnosed definitively as benign. CT urography with thin sections provides a detailed search of renal cysts for complicating features that might raise the possibility of a malignant cystic neoplasm. Thin section images can also be used to reduce partial volume averaging. As a result, attenuation measurements of renal masses can be obtained with more confidence. In general, attenuation measurements of a renal mass can be considered accurate only if the mass’s diameter is at least twice the image section thickness. For example, cysts as small as 6 mm may be characterized confidently with a CT urography protocol that includes 3-mm sections before and after contrast media administration but would likely not be measured accurately if 5-mm-thick sections had been obtained. Simple renal cysts can be differentiated from caliectasis as a result of reflux nephropathy (see Case 7-1), peripelvic cysts (see Case 7-4), and calyceal diverticula (see Case 7-5) by examining the excretory phase images obtained with CT urography because on excretory phase images, caliectasis and calyceal diverticula usually contain opacified urine, whereas renal cysts do not.

Case 7-3

History: 60-year-old female with left flank pain and left renal mass.

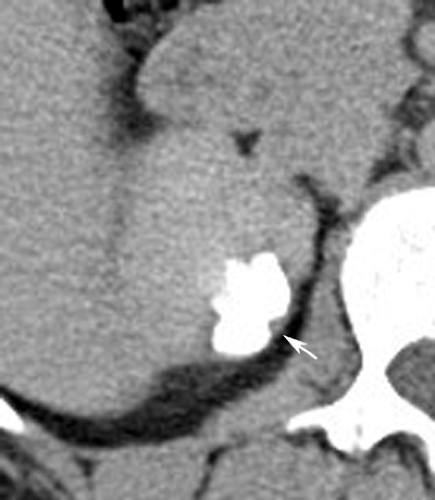

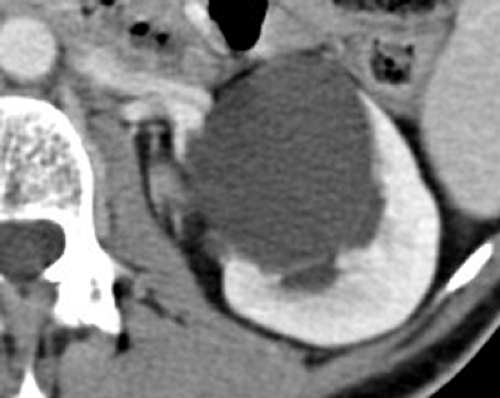

Findings: Axial unenhanced (A), nephrographic (B), and excretory (C) images from a CT urogram demonstrate a nonenhancing, low-attenuation, well-marginated, 4-cm cystic mass in the left kidney without septations or calcifications. Coronal image (D) shows mild hydronephrosis.

Diagnosis: Parapelvic cyst

Discussion: This mass fulfills all the CT-based criteria for a simple cyst. Approximately half of the cyst’s circumference is surrounded by renal parenchyma. This “claw sign” indicates that the cyst arises from the kidney. Since the cyst abuts the renal sinus and arises from the kidney, it is called a parapelvic cyst. Parapelvic cysts are typically solitary masses that may contain low-level echoes on sonography. Peripelvic cysts are typically multiple, often bilateral, and smaller than parapelvic cysts (see Case 7-4). Because of their central location, parapelvic cysts may cause mild obstruction of the infundibula and calyces. Cystic masses that are located in or around the renal hilum cannot be differentiated from the intrarenal collecting system on unenhanced and nephrographic phase images. Excretory phase images are needed to differentiate the collecting system (which in many cases contains opacified urine) from cystic masses (which do not).

Case 7-4

History: 52-year-old female with gross hematuria.

Figure 7.4 D (See color image.) |

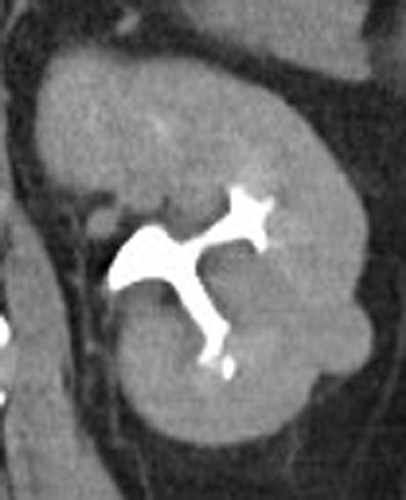

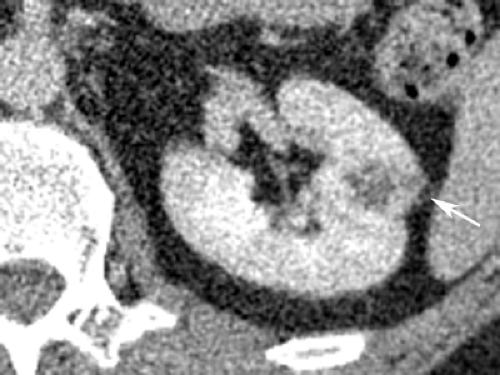

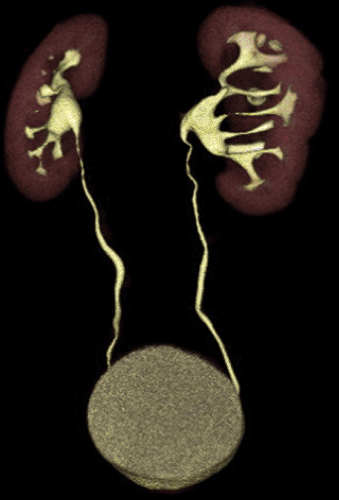

Findings: Axial unenhanced (A) and nephrographic phase (B) images show multiple, well-marginated, low-attenuation (<20 HU), nonenhancing masses in the renal sinus of the left kidney. A small (<1 cm), low-attenuation lesion in the renal parenchyma is almost certainly a cyst. Coronal reformatted image during the excretory phase (C) reveals the intrarenal collecting system filled with contrast material and demonstrates cystic masses on both sides of most infundibula. Volume-rendered image (D) does not directly display the cysts but, rather, their compressive effects on the attenuated adjacent opacified intrarenal collecting system.

Diagnosis: Peripelvic cysts

Discussion: Peripelvic cysts originate from renal sinus structures and insinuate themselves in the sinus fat. They are thought to be lymphatic in origin. This condition may also be referred to as congenital renal pelvic lymphangiectasia. In contrast, parapelvic cysts arise from renal parenchyma and expand into the renal sinus (see Case 7-3). Peripelvic cysts are common and usually multiple. They frequently distort the calyces and can attenuate and stretch the infundibula. Peripelvic cysts mimic hydronephrosis on ultrasound. CT urography displays the relation of the renal sinus cysts to the adjacent intrarenal collecting system. Peripelvic cysts can be difficult to distinguish from hydronephrosis on CT scans in which only unenhanced, corticomedullary, or nephrographic phase scans are obtained. CT urography, specifically the excretory phase images in the coronal plane, displays all components of the collecting system and shows how the infundibula and calyces are splayed by the cysts. If only volume-rendered images are utilized, as with excretory urography, the differential diagnosis would include peripelvic cysts and renal sinus lipomatosis.

Case 7-5

History: 28-year-old female with urinary frequency.

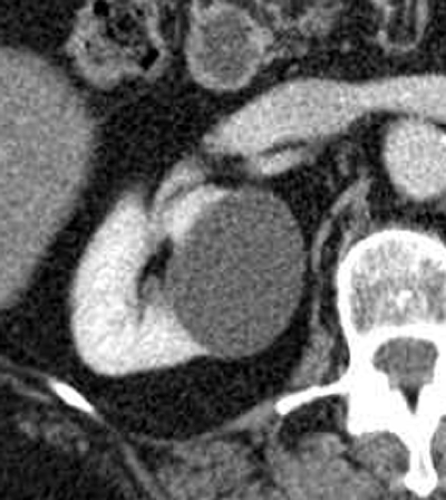

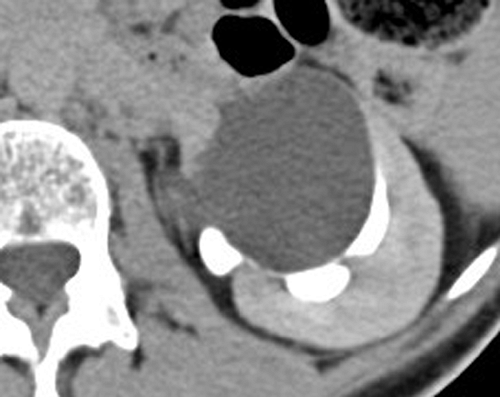

Findings: Axial unenhanced (A) and nephrographic (B) images from a CT urogram demonstrate a well-marginated, low-attenuation, nonenhancing, 2.5-cm cystic mass in the upper pole of the right kidney without septations or calcifications. The lesion fills with contrast material during the excretory phase (C). Maximum intensity projection image during the excretory phase (D) demonstrates a collection of contrast material situated lateral to an upper pole calyx.

Diagnosis: Congenital calyceal diverticulum

Discussion: Calyceal diverticula are congenital lesions that occur when one of the last generation of tubules in the first period of dichotomous division fails to expand as it normally would to form the infundibulum of a minor calyx and remains as a diverticulum (see Cases 4-13 and 8-4). Calyceal diverticula are lined by uroepithelium and communicate through a thin channel with the fornix of a calyx. They are usually asymptomatic, particularly when small. Calculi may develop and cause pain in large diverticula. Infection may also develop. A calyceal diverticulum may mimic a renal cyst or neoplasm if excretory phase images are not obtained. Calyceal diverticula usually fill with contrast material on excretory phase images; renal cysts and neoplasms almost always do not. The differential diagnosis on CT urography also includes residual abscess cavities and cysts that communicate with the collecting system.

Case 7-6

History: 57-year-old male with hematuria.

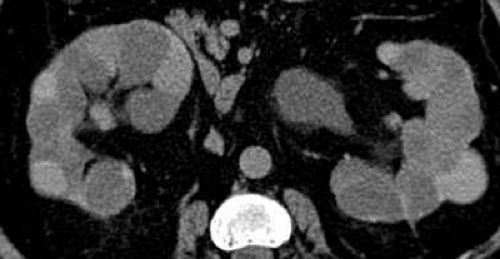

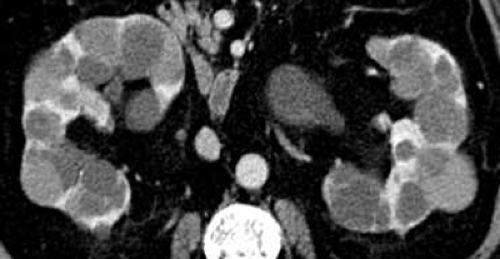

Findings: Axial unenhanced (A), nephrographic (B), and excretory (C) images show that both kidneys are enlarged and contain innumerable parenchymal cystic masses of varying sizes. Coronal reformatted image in the excretory phase (D) shows that the kidneys are also enlarged in the cephalocaudal dimension (14.0 cm on the right; 14.5 cm on the left). On the unenhanced image (A), some cysts are hyperdense (more dense than renal parenchyma). When each cystic mass’s attenuation was measured on both unenhanced and enhanced images, none enhanced.

Diagnosis: Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

Discussion: Autosomal dominant (adult) polycystic kidney disease is a hereditary disorder that usually manifests clinically in the third or fourth decade of life with hypertension, hematuria, or renal failure. Renal cysts develop as the patient ages, eventually completely replacing the renal parenchyma. Their appearance as innumerable, low-attenuation lesions at the nephrographic phase on intravenous urograms has been described as the “Swiss cheese” nephrogram, a term that also aptly describes their appearance on CT urography. Hemorrhage within some of the cysts results in their hyperdense appearance on CT. The cysts may also cause pain or become infected. Patients typically develop cysts in other organs, such as the liver (70%), pancreas (10%), spleen (5%), and, rarely, the ovary and thyroid. Intracranial berry aneurysms develop in 20% of patients. End-stage renal disease occurs in 45% of patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease by the age of 60 years.

Case 7-7

History: 52-year-old male with urinary incontinence and retention and an incidentally detected cystic renal mass on ultrasound.

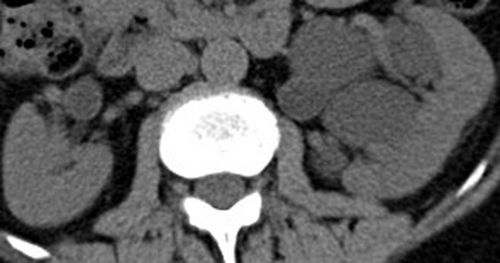

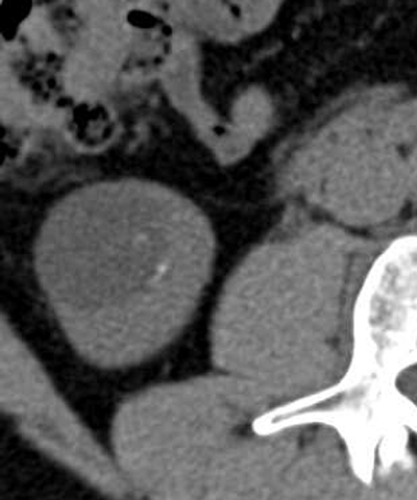

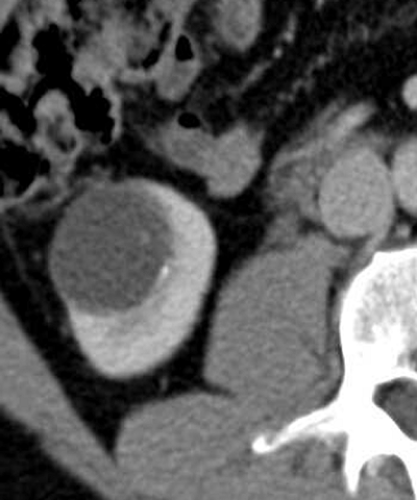

Findings: Axial unenhanced (A), nephrographic (B), and excretory (C) phase images from a CT urogram demonstrate a 3.8-cm, low-attenuation mass in the lower pole of the right kidney that contains a thin septation and thin calcifications in both the septation and the medial wall of the mass (A). Coronal excretory phase image (D) demonstrates that the septation is thin and enhancing, as evidenced by the fact that the septation is seen more clearly with contrast media than without it.

Diagnosis: Benign, complicated renal cyst

Discussion: Cystic renal masses that contain few (<3), thin (1 or 2 mm) septations are classified as Bosniak category II cystic masses. Calcifications may be present, as long as they are small and border forming (i.e., located in the wall or septation). Bosniak category II cystic masses, which also include hyperdense cysts (see Case 7-8), are reliably considered benign on imaging findings alone. Renal masses that contain more thin septations, thick or nodular calcifications, or those masses that fulfill the criteria for a hyperdense cyst but are >3 cm or intrarenal are considered Bosniak category IIF lesions. These masses are usually benign but should be followed. The “F” refers to the need for follow-up imaging. CT urography provides thin section evaluation of the mass’s features before and after contrast media administration.

Case 7-8

History: 46-year-old female with an incidental renal mass.

Findings: Axial unenhanced (A) and nephrographic phase (B) images from a CT urogram demonstrate a 1.1-cm, homogenously hyperdense (70 HU), exophytic mass in the lateral aspect of the lower pole of the left kidney. Nephrographic phase image demonstrates that the mass’s attenuation remains the same (70 HU); therefore, the mass does not enhance. Coronal excretory phase image obtained at 15 minutes after contrast media administration (C) also demonstrates that the mass’s attenuation is unchanged.

Diagnosis: Benign, hyperdense renal cyst

Discussion: Renal masses that are denser than renal parenchyma (i.e., >40 HU) are considered hyperdense and usually measure 50 to 90 HU. Most hyperdense renal masses are benign hyperdense cysts, as in this case. These cysts, as in Case 7-7, are classified as Bosniak category II cysts and are likely benign. However, a diagnosis of a benign, hyperdense cyst requires all the following criteria to be fulfilled: the mass must be small (≤3 cm), homogeneously hyperdense (even using a narrow window setting), well-marginated, nonenhancing, and have at least one-fourth of its circumference extend outside the renal parenchyma so a portion of its wall can be evaluated. A high concentration of protein or blood breakdown products is responsible for their high attenuation. If a hyperdense mass is noted on an enhanced CT alone and the study is being monitored, 15-minute delayed CT can be performed to determine the presence of wash-out of contrast media or “de-enhancement.” If the mass de-enhances, the mass can be considered solid and neoplastic (excluding vascular abnormalities). However, if the mass does not de-enhance, it can be reliably considered a benign, hyperdense cyst.

Case 7-9

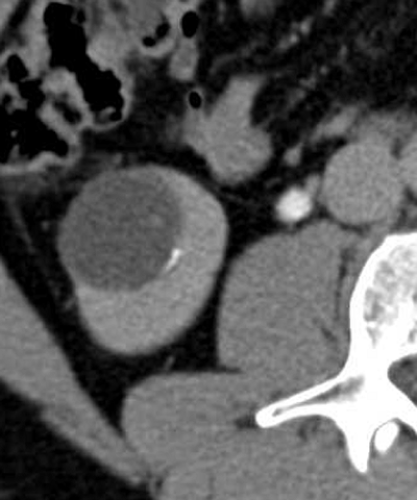

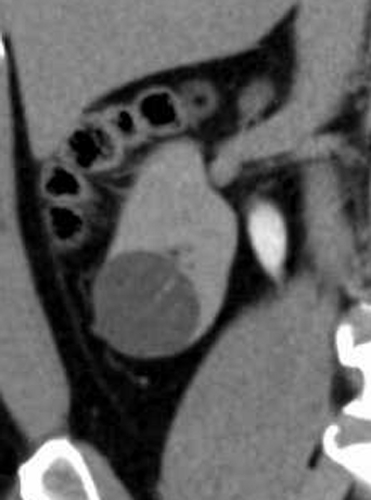

History: 42-year-old asymptomatic male potential kidney donor.