- Renal artery stenosis (RAS) may present as drug-resistant hypertension, acute kidney injury (especially with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) use), chronic renal impairment or recurrent flash pulmonary oedema.

- The most common pointers to clinical diagnosis of RAS are the presence of femoral, renal or aortic bruits and the coexistence of severe extra-renal vascular disease.

- RAS should be considered when marked deterioration in renal function (e.g. ≥30% increase in creatinine or ≥ 25% fall in eGFR) occurs when an ACEI or ARB is used.

- Atheromatous renovascular disease (ARVD) is the cause of 90% of cases of RAS, and it can be unilateral or bilateral.

- Post-mortem studies indicate the presence of ARVD in over 40% of older patients. ARVD does not cause significant hypertension or chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the majority of patients.

- Approximately 5–10% of RAS cases are due to fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), typically found in hypertensive young women. Angioplasty can cure hypertension in about a third of this group of patients.

- There are several screening methods for RAS.

- Both renal arteriography and angioplasty have significant risks to the patient, which should be considered.

- Renal artery angioplasty and stenting are effective at improving renal artery stenoses for both ARVD and FMD. However, only in FMD can one expect a significant improvement in blood pressure (BP) control in the majority of patients.

- ARVD should be considered as part of a diffuse vascular disease process, and management should involve control of hypertension and hyperlipidaemia, use of antiplatelet agents and cessation of smoking.

- ACEI and ARBs are amongst the optimal anti-hypertensive choices for patients with ARVD, although care and specialist advice may be necessary if marked renal deterioration is found following the administration of such medication.

Definition and Background

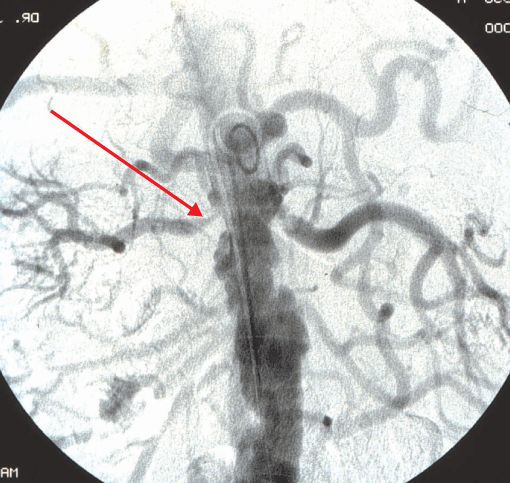

Renal artery stenosis (RAS) is a reduction in the lumen of one or both renal arteries, and can be an important cause of renal failure and secondary hypertension. In >90% of cases the condition is due to atheroma of the renal arteries (atheromatous renovascular disease, or ARVD; Figure 8.1), and this is a disease of ageing. Patients usually have evidence of atheroma in other important vascular beds, such as coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular and peripheral vascular disease (PVD), and RAS involves the renal ostia (renal arterial origins) in 90% of cases. ARVD can be unilateral or bilateral and up to 50% of patients have renal artery occlusion (RAO) at diagnosis. It is very common: post-mortem studies indicate its presence in over 40% of older patients.

Figure 8.1 Renal arteriogram showing atheromatous renal artery stenosis. A flush aortogram: note the irregular shape of the aorta due to atheroma. The red arrow points to marked reduction in the arterial lumen of the renal artery. Atheromatous RAS typically involves the ostia of the renal arteries, as these are involved with aortic atherosclerotic lesions.

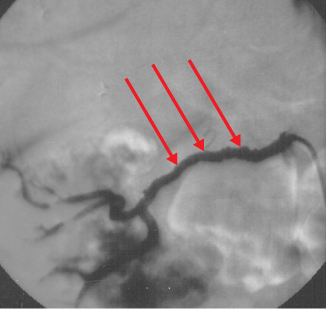

Approximately 5–10% of RAS cases are due to fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD; Figure 8.2), which, when it is discovered, is typically seen in hypertensive young women, most of whom have well-preserved renal function. In contrast to ARVD, angioplasty of FMD RAS lesions is usually associated with clinical improvement, such as cure of hypertension in a third of patients.

Figure 8.2 Renal arteriogram showing fibromuscular renal artery stenosis. A selective right renal artery angiogram in fibromuscular RAS (FMD). The aorta is not affected by atheroma. The red arrows point to multiple bead-like irregularities in the lumen of the renal artery well away from the ostium. A nephrogram can be seen, and there is contrast in the renal collecting system and ureter.

Although many patients with ARVD will have hypertension and/or chronic kidney disease (CKD), in the vast majority of patients it is likely to be incidental and pathophysiologically insignificant to these latter conditions. This explains the inconsistent results following renal artery intervention in ARVD, which has led to uncertainty in guidelines for its management. Assessing the severity of a stenosis and having a thorough understanding of the clinical context are essential to planning management. Most RAS will be suspected, diagnosed and treated in a hospital setting. One important exception is a change in renal function with the introduction of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), as numerically the majority of scripts for hypertension and heart failure are community-based.

Clinical Features

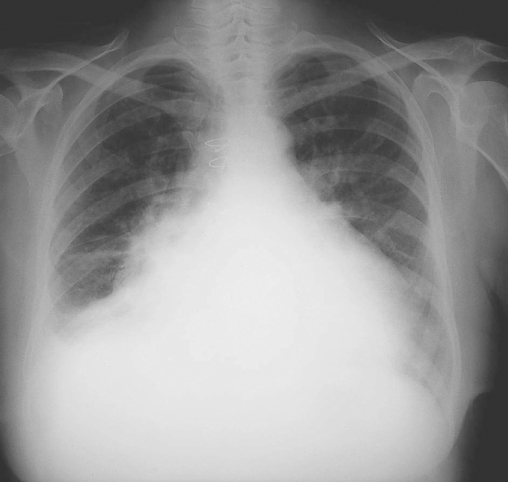

Although the majority of ARVD cases are asymptomatic, the condition should be suspected in patients presenting with renal dysfunction and hypertension who have evidence of atheromatous disease in other vascular beds. Particular clinical features include significant deterioration of renal function (e.g. ≥30% increase in serum creatinine or ≥ 25% fall in estimated glomerular filtration rate, or eGFR) accompanying use of ACEI or ARBs, or unexplained ‘flash’ (sudden onset) pulmonary oedema (Figure 8.3), but the presence of femoral, renal or aortic bruits and the coexistence of severe extra-renal vascular disease are the commonest clinical pointers to diagnosis. Hypertension may be absent, particularly in patients with chronic cardiac dysfunction, but a high index of suspicion for RAS diagnosis is advised in cases with severe (often systolic) hypertension, especially when unresponsive to three or more anti-hypertensive agents and with evidence of widespread vascular disease. Box 8.1 lists some of the important clinical clues to the presence of RAS.

Figure 8.3 ‘Flash’ pulmonary oedema. A chest X-ray showing shows florid bilateral pulmonary oedema, which was the presentation of severe RAS in this patient.