(1)

Department of Vascular Surgery, Evangelisches Krankenhaus Königin Elisabeth Herzberge, Berlin, Germany

Thrombosis, aneurysms, stenoses, and infections are possible causes for redo surgery. In the previous chapters we presented the typical procedures for the correction of stenoses of venous anastomoses and draining veins of different AV access variants. The same principles apply to thrombectomies and reconstructions of long segment stenoses of prosthetic grafts. A special extra chapter deals with infections.

6.1 Thromboses

Thrombectomies of a prosthetic graft are similar to those of AV fistulas. They entail:

Removal of a thrombus

Investigation into its cause

6.1.1 Finding the Cause of Thrombosis

This is a three-stage procedure involving history, clinical examination, and intraoperative findings.

History

Signs of impaired venous drainage are:

Prolonged bleeding after puncture

Raised pressure of venous line during dialysis

Decrease of thrill and increased pulsation

Signs of diminished arterial inflow are:

Decreased thrill

Low flow during dialysis

Arterial hypotension or hypotensive episodes may also be contributing factors.

Hypercoagulability for infectious or other reasons leads to an increased risk for thrombosis.

Clinical Examination

Stenoses or occlusions of draining veins may show by distended superficial veins.

A tightly filled shunt prosthesis is typical for a stenosis of the venous anastomosis.

Large aneuryms with thrombi that are adherent to the walls may cause occlusions.

Infections of the shunt may also favor thrombosis.

Intraoperative Findings

Catheter Thrombectomy

During thrombectomy procedures using a Fogarty catheter, an experienced surgeon can evaluate the lumen of grafts and anastomoses.

Intraoperative Angiography

Routine intraoperative angiography showing both anastomoses after thrombectomy is desirable. It should be performed if stenoses of the prosthesis, the anastomoses, or the feeding or draining vessels are suspected

Evaluation of the Thrombi

With predominantly red thrombi, a hypercoagulable state is unlikely.

With hypercoagulability, thrombi are mixed or predominantly white.

Whitish circular adhesions to the prosthetic wall which look like tubes when they are removed by the thrombectomy catheter and occur when hypotension, venous or arterial stenoses, or hypercoagulability cause low flow.

6.1.2 Choice of the Thrombectomy Site

Three aspects deserve attention:

Preservation of puncturable segments.

Opportunity to repair an underlying stenosis.

Chance to reach both anastomoses with the catheter.

The incision is different for straight and looped grafts.

Straight Grafts

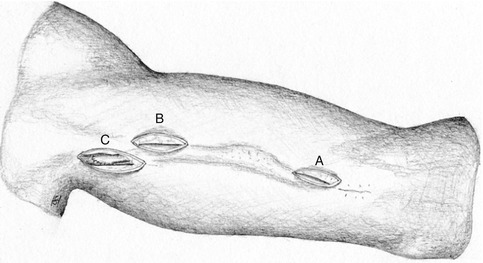

If there is no suspicion of a stenosis of the venous anastomosis, the graft should be exposed near the venous or arterial anastomosis where it is not punctured (Fig. 6.1, incisions A or B). If you suspect a stenosis of the venous anastomosis, you should expose it (incision C).

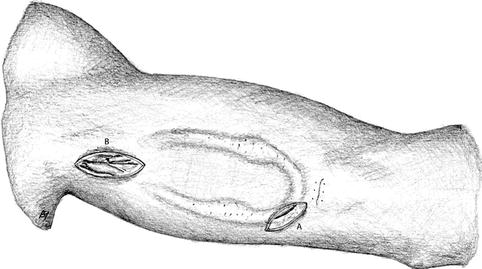

Fig. 6.1

Incisions for thrombectomies of straight grafts. If there is no suspicion of a stenosis close to the venous anastomosis, the puncturable segment should be spared (A or B). Otherwise isolate the venous anastomosis (C)

Loop Grafts

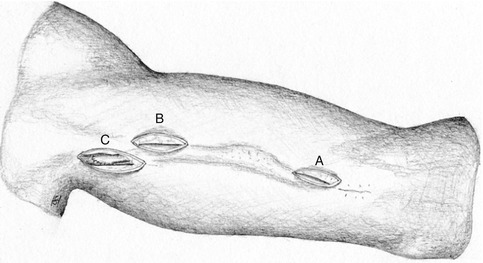

If there is no suspicion of a venous stenosis, the graft should be exposed near its apex, which is equidistant from both anastomoses (Fig. 6.2, incision B). If you suspect a stenosis of the venous anastomosis, you should then expose it (incision A).

Fig. 6.2

Incisions for thrombectomies of loop grafts. If there is no suspicion of a stenosis close to the venous anastomosis, the graft is exposed near its apex (A). Otherwise isolate the venous anastomosis (B)

6.1.3 Incision

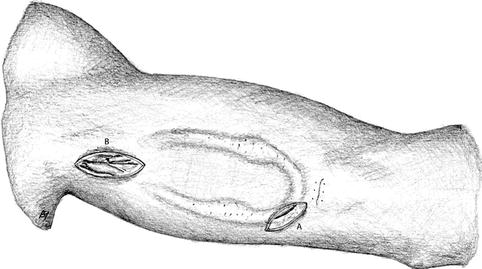

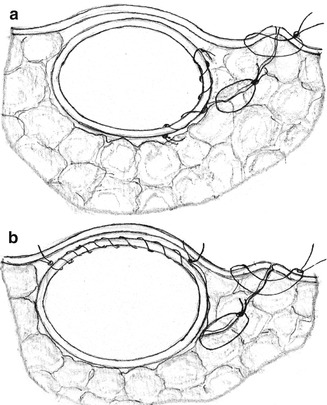

Except for the areas directly adjacent to the anastomoses, the graft lies in a subcutaneous tunnel. In order to avoid wound infections, the incision for thrombectomy should be parallel to the prosthesis, leaving enough subcutaneous tissue to cover the prosthesis when closing the wound (Fig. 6.3). The skin incision should be long enough to be able to complete the suture of the clamped vessel (mostly 2.5–3.5 cm). A lateral graft incision helps hide the knotted ends of the suture in the subcutaneous tissue so that they don’t pierce the skin surface. This might lead to a cutaneous fistula and subsequent graft infection (Fig. 6.4a, b).

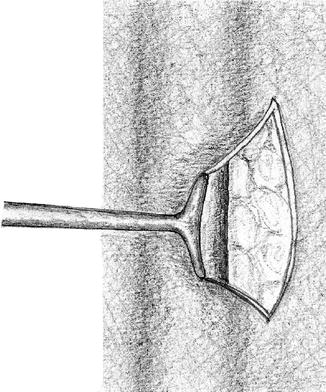

Fig. 6.3

Exposure of the prosthesis via a lateral longitudinal incision

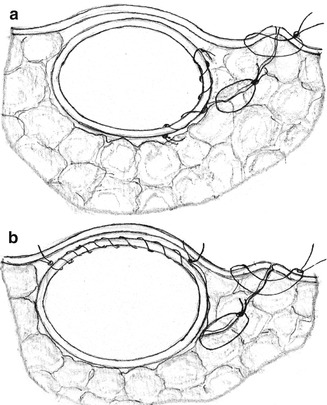

Fig. 6.4

Different options for graft incisions: (a) lateral and (b) towards the skin surface with a risk of a thread perforating the skin

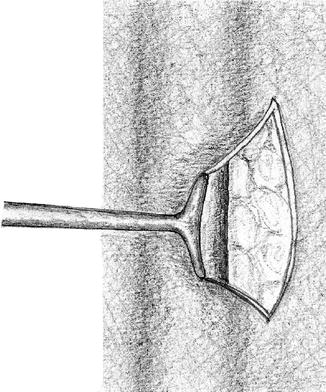

6.1.4 Technique for Thrombectomy

After the sufficient circular exposure of the prosthesis, a lateral transverse incision is made to open it. We recommend performing thrombectomy of the venous side first. Care should be taken to remove the end of the thrombus (Fig. 6.5) from the anastomosis. It is characterized by its concave and lighter surface. If you have not found it, you should continue with the thrombectomy maneuver. During the clamping period, the sides which have already been freed of thrombi should be filled with heparin solution (e.g., 5,000 I.U. of heparin per 100 mL normal saline). Frequently it proves difficult to remove adherent white thrombi. Then flexible remote annular cutters (e.g., Fehling company) may also be useful for loop grafts (Fig. 6.6). A titanium spiral probe (e.g., Fehling company) may also prove helpful when cleaning off strongly adherent material (Fig. 6.7).