and Chao-Hui Zheng1

(1)

Department of Gastric Surgery, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, Fuzhou, China

Reconstruction of the digestive tract after laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer is an important aspect of clinical efficacy, which concerns postoperative recovery and quality of life. With prolonged survival of patients with gastric cancer, the postoperative quality of life deserves more attention. Researchers have paid increasing attention to reconstruction methods. As a result of the widespread application of laparoscopic techniques, reconstruction of the digestive tract after laparoscopic gastrectomy has become a research focus in surgery.

8.1 Outline of Reconstruction After Laparoscopic Radical Gastrectomy

8.1.1 Reconstruction Approach After Laparoscopic Gastrectomy

Laparoscopic gastrectomy is superior to conventional open gastrectomy because it is less invasive, which may lead to smaller wounds, faster recovery, fewer complications, and better cosmetic results. In addition, better clinical efficacy is achieved [1–4]. Currently, reconstruction of the digestive tract following laparoscopic gastrectomy is mostly divided into two categories: laparoscopy-assisted reconstruction and totally laparoscopic reconstruction. With laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy (LAG), mobilization of the digestive tract, vascular ligation, and lymph node dissection are performed laparoscopically, while resection of the specimen and reconstruction of the digestive tract are performed under direct view through a minilaparotomy made on the epigastrium. The resected specimen mostly has to be removed via the minilaparotomy made on the epigastrium. Furthermore, the anastomosis can be performed with less difficulty, shorter operating time, and lower cost when surgery is performed through minilaparotomy, and this is a safe and feasible method. Thus, LAG has become a common approach in laparoscopic surgery.

Laparoscopic techniques were developed to achieve a radical cure with minimal invasion and to improve postoperative quality of life. Compared with LAG, totally laparoscopic gastrectomy (TLG) is considered to be more minimally invasive and has several superiorities in vision and tension, particularly for obese patients. Therefore, researches on the application of TLG have never stopped.

In 1996, Ballesta-Lopez et al. first reported Billroth-II anastomosis in totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (TLDG) for gastric cancer [5]. Uyama et al. first described totally laparoscopic side-to-side esophagojejunostomy after total gastrectomy in 1999 [6]. A method for intracorporeal Billroth-I anastomosis, called delta-shaped gastroduodenostomy (DSG) and using only endoscopic linear staplers, was first reported in 2002 by Kanaya et al. [7]. In 2005, Takaofi et al. proposed a secure technique of intracorporeal Roux-Y reconstruction after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy using linear staplers [8]. Intracorporeal circular stapling esophagojejunostomy using the transorally inserted anvil (OrVil™; Covidien) after laparoscopic total gastrectomy was reported in 2009 by Jeong et al. [9]. With improvements of surgical skills and dedicated intracorporeal devices, such as linear staplers and ultrasonic scalpels, Billroth-I, Billroth-II, and Roux-en-Y reconstruction, which are usually performed by open surgery, can all be performed laparoscopically.

8.1.2 Technical Tips of Reconstruction After Laparoscopic Radical Gastrectomy

8.1.2.1 Pay Attention to Operational Details and Avoid Unnecessary Injury

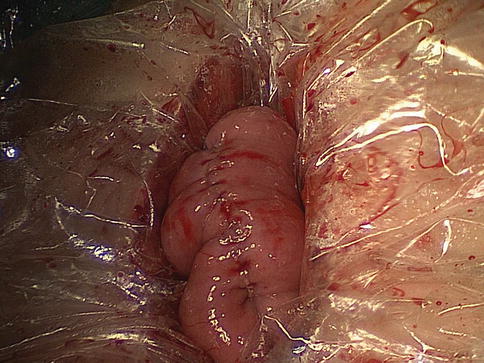

The details should be noted during the operation to avoid rework or contamination of the operating field, thus avoiding unnecessary trauma. For example, the gastric tube set up before surgery should be positioned at the appropriate location before anastomosis to prevent it being severed by the linear stapler. The specimen should be placed in a plastic specimen bag to ensure aseptic and tumor-free conditions. The principle of aseptic technique should be followed during making incisions in the digestive tract, and the digestive juice can be aspirated clearly using an aspirator inserted into the incisions before anastomosis.

8.1.2.2 Ensure Quality of the Anastomosis and Reduce the Postoperative Complications

At present, anastomosis-related complications mainly include anastomotic leakage, hemorrhage, and stenosis. Adequate blood supply to the tension-free anastomosis is the key to prevention of anastomotic leakage. However, the formation of scar tissues after healing of the intestinal wall or too much stitching is a common cause of anastomotic stenosis. With respect to the prevention of anastomotic hemorrhage, a common stab incision is created during anastomosis using a linear stapler; the anastomosis should be checked for bleeding or mucosal damage via the common stab incision. After anastomosis, the integrity of the stapler nails should be checked, including whether the anastomotic stoma and resected tissue are a complete circle in the circular stapler. If the anastomosis is not satisfactory or there is oozing of the blood, manual sutures can be added for reinforcement. The surgeon must carefully operate step-by-step to ensure that each stage in the anastomosis is practical and reliable. Thus, better postoperative quality of life can be achieved.

8.1.2.3 Familiarity with Instruments’ Use to Reduce Trauma

A variety of instruments are needed to assist in the completion of totally laparoscopic reconstruction of the digestive tract, so it is necessary to be familiar with the performance of all kinds of laparoscopic instruments and techniques to avoid trauma from the instruments themselves. In the process of using the instruments, the following points should be noted: (1) cartilage-type staplers should be adapted to the thickness of the tissue; (2) the diameter of the stapler should be adapted to the diameter of the intestinal canal; (3) the gastric tube should be pulled out before firing the stapler, and overall inspection should be conducted to make the anastomosis site appropriate and prevent the stapler from clamping other structures; (4) after firing the stapler, the handle should be firmly squeezed for >15 s to expel the interstitial fluid, thus achieving a better stapling result; (5) the stapler should be fired completely, therefore, and the firing shaft will touch the closing shaft to stop the stapler from mistakenly firing or locking; and (6) during transection of specific positions such as the duodenum, the flexible stapler can be used to facilitate operation, and at this moment, the jaws should be opened because the stapler cannot bend at the tip if the jaws are closed.

8.2 Reconstruction of the Digestive Tract After LAG

Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) is the earliest laparoscopic procedure in the field of gastric surgery. Currently, this procedure has been the most commonly performed for gastric cancer. With the increasing incidence of proximal gastric cancer and application of laparoscopic techniques for treatment of advanced gastric cancer, laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) has gradually become popular. Here, we introduce Billroth-I anastomosis in LADG and Roux-en-Y anastomosis in LATG.

8.2.1 Technical Tips of Billroth-I Anastomosis in LADG

Mobilization of the stomach and lymph node dissection should be carried out completely by laparoscopy to prepare for successful reconstruction of the digestive tract through minilaparotomy. One should try to avoid other redundant operations through the minilaparotomy.

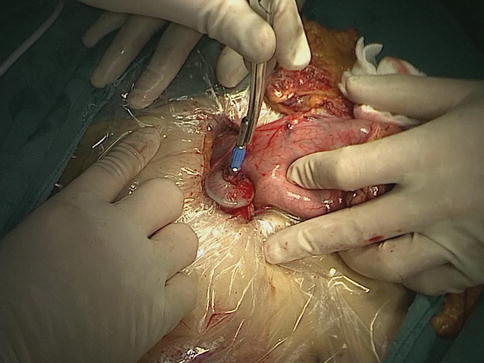

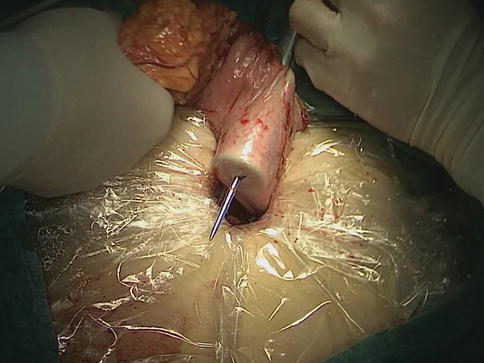

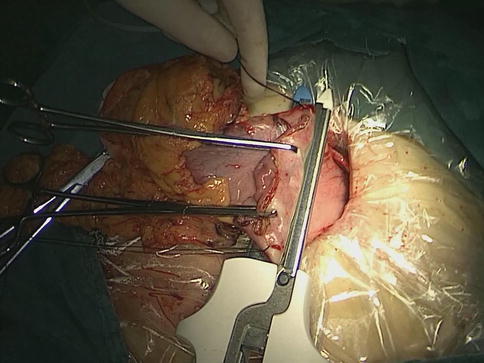

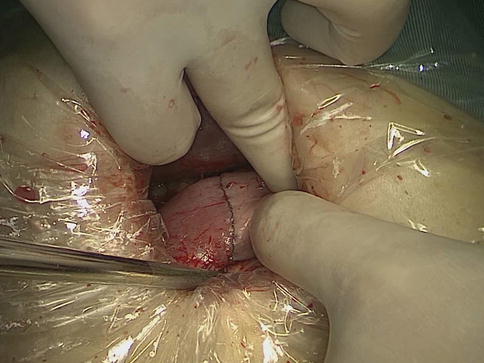

After the distal stomach is freed and the lymph nodes (LNs) are dissected, the intra-abdominal gas is expelled from the trocar, and the laparoscopic instruments are removed. A 5–7-cm midline incision below the xiphoid is made in the epigastrium as an accessory incision. The abdominal cavity is entered layer-by-layer, and the wound protector is placed in position. After complete retrieval of the duodenum from the abdominal cavity, a purse-string clamp is applied to the duodenum 3 cm distal to the pylorus. A Kocher clamp is applied just proximal to the purse-string clamp, and the duodenum is transected between the two clamps. The anvil of a disposable 28- or 29-mm circle stapler is inserted into the disinfected duodenal stump (Fig. 8.1), and a purse-string suture is tied over the anvil. Gastrotomy is performed on the anterior wall 5 cm away from the tumor edge and the shaft of the circular stapler is introduced into the stomach through the gastrotomy. The center rod of the stapler is advanced to penetrate the posterior wall at the greater curvature side of the stomach (Fig. 8.2) and then connected to the anvil placed in the duodenal stump, completing the end-to-side gastroduodenostomy between the duodenal stump and the gastric posterior wall (Fig. 8.3). After checking and confirming the quality of the anastomosis through the gastrotomy under direct view, the stomach is closed 5 cm away from the tumor edge using the extracorporeal linear stapler (Fig. 8.4). The resected distal gastric specimen is sent for histopathological examination. Thus, Billroth-I reconstruction is accomplished (Fig. 8.5). Although the visual field and working space are narrow during laparoscopy-assisted reconstruction, every step of the procedure should be completed under direct view, which avoids iatrogenic injury or uncertain anastomosis caused by blind operation.

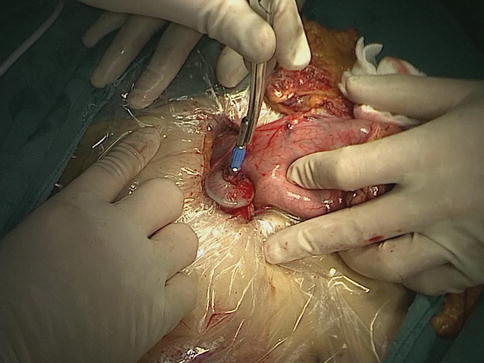

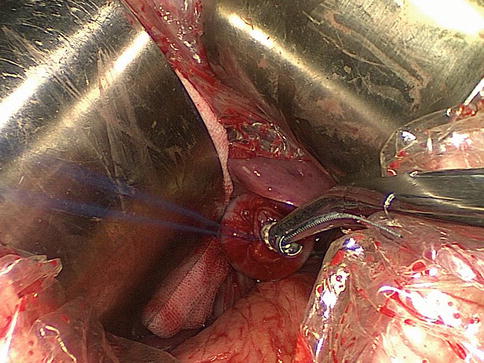

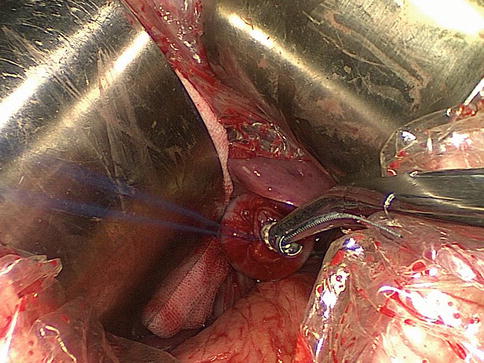

Fig. 8.1

The anvil of a disposable circle stapler is inserted into the duodenal stump

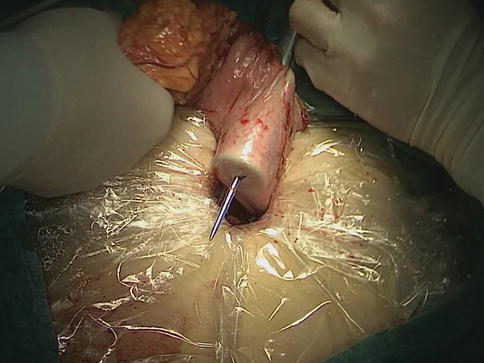

Fig. 8.2

The center rod of the stapler is advanced to penetrate the posterior wall at the greater curvature side of the stomach

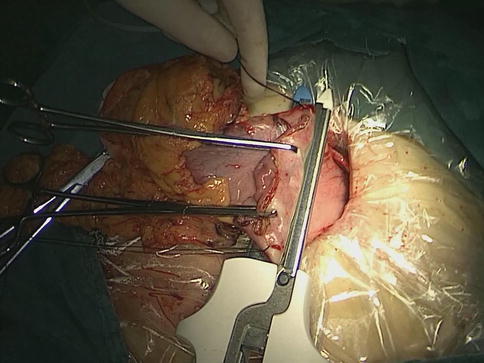

Fig. 8.3

The end-to-side gastroduodenostomy is performed

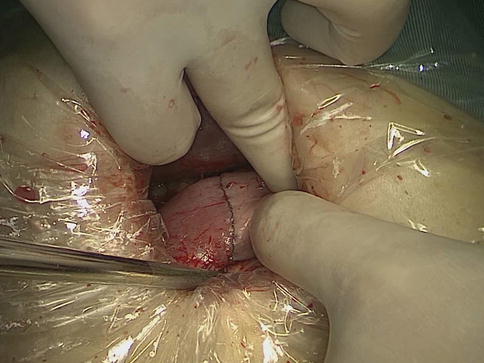

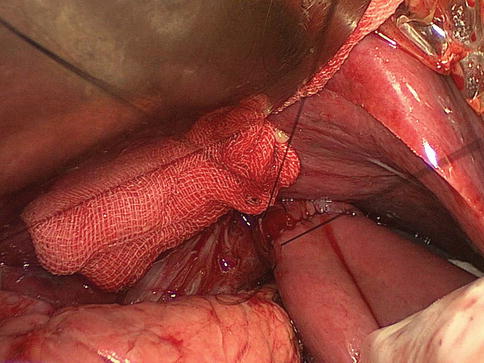

Fig. 8.4

The anterior and posterior walls of the stomach are closed 5 cm away from the tumor edge using the extracorporeal linear stapler

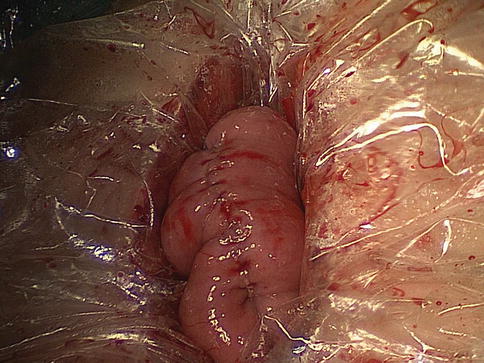

Fig. 8.5

Billroth-I reconstruction is accomplished

8.2.2 Technical Tips of Roux-en-Y Anastomosis in LATG

After completing lymph node dissection and mobilization of the stomach laparoscopically, the duodenal bulb is transected 3 cm distal to the pylorus using the intracorporeal linear stapler, and the duodenal stump is closed. The laparoscopic instruments are removed, and a 5–7-cm upper midline abdominal incision below the xiphoid is made as an accessory incision. The abdominal cavity is entered layer-by-layer, and the wound protector is placed in position. A purse-string clamp is applied to the distal esophagus 5 cm away from the cardia and the esophagus is transected. Thereafter, a purse-string suture is placed in the disinfected esophageal stump. Once the frozen section confirms negative margins, the anvil of a disposable 25-mm circular stapler is inserted into the esophageal stump (Fig. 8.6), and the purse-string suture is tied over the anvil. The entire gastric specimen is delivered out through the minilaparotomy. The jejunum and the mesentery are cut off 15–20 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz. The body of the circular stapler is inserted into the distal limb of the jejunum, and this section of jejunum is brought up in antecolic fashion to meet the lower end of the esophagus, creating the end-to-side esophagojejunostomy with the jejunum configured in a “J” fashion (Fig. 8.7). The stumps of distal and proximal jejunum are closed respectively using the linear stapler. A side-to-side jejunojejunostomy is performed 40 cm distal to the J-shaped anastomosis under direct view using a linear stapler or hand-sewn suture (Fig. 8.8). The proximal and distal end of the mesojejunum should not be reversed and the mesentery should be maintained without tension, to prevent improperly clamping the surrounding tissues and foreign object. The cutting edge of mesojejunum can then be closed to accomplish the entire procedure of reconstruction.

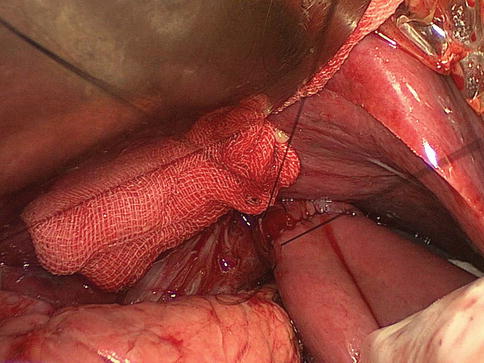

Fig. 8.6

The anvil of a disposable 25-mm circular stapler is inserted into the esophageal stump

Fig. 8.7

The end-to-side esophagojejunostomy is performed

Fig. 8.8

The side-to-side jejunojejunostomy is accomplished

8.3 Reconstruction of the Digestive Tract After TLG for Gastric Cancer

8.3.1 Characteristics of Reconstruction After TLG

8.3.1.1 Superiorities of TLG for Gastric Cancer

Surgical treatment of gastric cancer has improved as a result of the emergence of reconstruction after TLG. The superiority of laparoscopic reconstruction is related to its smaller incisions and less touch and surgical trauma. Related reports indicate that TLG has several advantages over LAG in terms of short-term outcomes, such as less intraoperative blood loss, smaller wounds, earlier recovery of gastrointestinal function with time to first flatus shortened, and shorter hospital stay [1, 10–13]. The operating time is shorter because of accumulated surgical experience [14, 15]. There are no significant differences between TLG and other procedures [10, 11]. In terms of perioperative and long-term complications, TLG does not increase the incidence of major complications (e.g., hemorrhage, anastomotic leakage, and stump leakage) and minor complications (e.g., incision infection and lymphatic leakage) [10, 16–20]. The superiority of TLG for obese patients is also supported by results from multicenter studies. The advantages of TLG mainly include more convenient anastomosis, better visualization, and better quality of life [16, 21, 22]. Additionally, TLG ensures adherence to the principals of tumor resection, such as the no-touch technique and no extrusion. Stomach resection and anastomosis are performed in situ, which reduces anastomotic trauma and additional pulling on the remnant stomach. Therefore, laparoscopic surgeons are increasingly focusing on reconstruction of digestive tract in total laparoscopy.

8.3.1.2 Influence of the Staplers for Anastomosis on Laparoscopic Reconstruction of the Digestive Tract

The widespread application of laparoscopic appliances has become an indispensable factor in the advancement of laparoscopic surgery for gastric cancer. Continuous improvement of the staplers for anastomosis has simplified reconstruction of the digestive tract, and the time for anastomosis has been shortened. Anastomosis using staplers, which is technically safe and feasible, has similar results and complication rates to anastomosis using hand-sewn sutures. Furthermore, in TLG, the application of the staplers has shortened the time for anastomosis. The complex operative manipulations due to the difficult exposure and limited work space are also made easier. Laparoscopic anastomosis is simplified, and the contamination of the abdominal cavity and the surgical trauma are reduced, which improves the efficacy of surgical treatment. Novel stapler production offers new techniques for laparoscopic reconstruction, for example, the transorally inserted anvil (OrVil™) is used in esophagojejunostomy for Roux-en-Y anastomosis after laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Anastomosis using staplers has the following advantages: (1) small vessels can pass through the intervals between the staplers, so as not to affect the blood supply of the anastomotic site and its distal end; (2) the stapler is made of titanium or tantalum; therefore, tissue reactions are reduced compared with hand-sewn anastomosis; and (3) the staplers are neatly arranged at equal intervals, which ensures good tissue healing.

8.3.2 Indications for Totally Laparoscopic Reconstruction of the Digestive Tract

Reconstruction of the digestive tract should be performed within a certain distance of the normal tissues. The normal tissues at a certain distance from the proximal or distal border of the tumor must be resected according to tumor location and TNM staging. Preoperative laparoscopic exploration is performed first to confirm the tumor site. Patients with T4b tumor, peritoneal implantation, or liver metastasis should be excluded. If it is difficult to identify the tumor site in early tumors during total laparoscopy, intraoperative gastroscopy can be used for accurate positioning to ensure R0 resection of the tumor. Transection of the duodenum, stomach, or esophagus should ensure not only R0 tumor resection but also appropriate anastomotic tension. The resected margins should be confirmed as tumor free, and the margin of the removed specimen must be sent for frozen section analysis prior to proceeding with anastomosis.

8.3.2.1 Reconstruction of the Digestive Tract After Distal Gastrectomy

The delta-shaped Billroth-I anastomosis may be more suitable for patients diagnosed with early primary distal gastric cancer, whereas it may be used for clinical investigation in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer [23, 24]. When a tumor has invaded the pyloric canal or duodenum, Billroth-II anastomosis can be performed to achieve R0 resection [25]. In distal gastrectomy, two-thirds to three-quarters of the distal stomach should be resected, including the distal gastric body, antrum, pylorus, and proximal duodenal bulb. The line between the right side of the first descending branch of the left gastric artery (LGA) and the left side of the lowest vertical branch of the left gastroepiploic artery (LGEA) can be used to mark the extent of gastric resection. The greater curvature of the stomach should be denuded, preserving two to three branches of short gastric arteries and the posterior gastric artery (SGAs and PGA) to ensure the blood supply for the remnant stomach, reduce the anastomotic tension, and facilitate anvil of the linear stapler insertion.

8.3.2.2 Reconstruction of Digestive Tract After Total Gastrectomy

Laparoscopic total gastrectomy with functional end-to-end esophagojejunostomy is more suitable for patients with non-cardia upper or middle gastric cancer. Laparoscopic total gastrectomy can also be performed for patients with early cardial cancer or localized cardial cancer invading the abdominal esophagus <1–2 cm, with the secure cutting line of the esophagus under the esophageal hiatus [26]. Anastomosis using OrVil™ is appropriate for patients with laparoscopically resectable early proximal gastric carcinoma, which invades the distal esophagus within 3 cm above the gastroesophageal junction (visualized by preoperative X-ray barium meal) and has no obvious external invasion in the preoperative evaluation of the tumor [27]. For patients with a tumor of the non-cardia proximal stomach or gastric body, only the abdominal esophagus should be freed. When the tumor is located at the cardia or invades the distal esophagus, it must be removed. The esophageal hiatus can be adequately extended by incising the diaphragm at the vault of the esophageal hiatus 4–5 cm in the ventral direction. The left triangular ligament can be severed to facilitate the exposure. The middle to lower part of the crus of the diaphragm is transected on both sides, and the pleura is pushed toward both sides to extend fully the space of the posterior mediastinum; thus, the jejunum can be sent into the posterior mediastinum for anastomosis with the esophagus.

8.3.3 Procedures of Reconstruction After TLG

Currently, there are a variety of reconstruction methods after TLG for gastric cancer, including Billroth-I anastomosis, Billroth-II anastomosis, and Roux-en-Y reconstruction after TLDG, and functional side-to-side esophagojejunostomy, OrVil™-assisted anastomosis, and overlap anastomosis after totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy (TLTG). Here, the more mature techniques of delta-shaped Billroth-I anastomosis and Billroth-II anastomosis after TLDG, functional side-to-side esophagojejunostomy, and OrVil™-assisted anastomosis after TLTG are described. The patient’s position, surgeons’ locations, and location of trocars are identical to those during the process of lymph node dissection (described in Chap. 3).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree