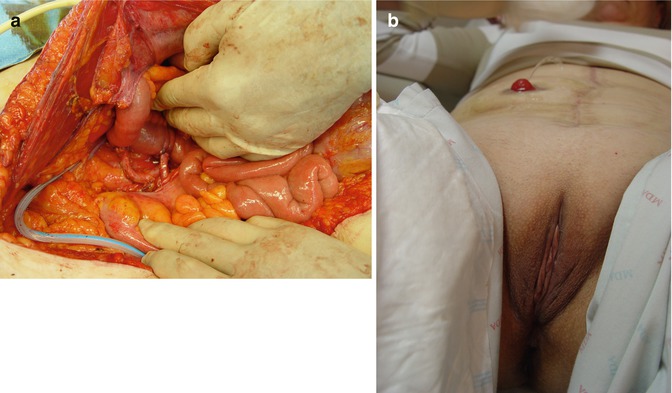

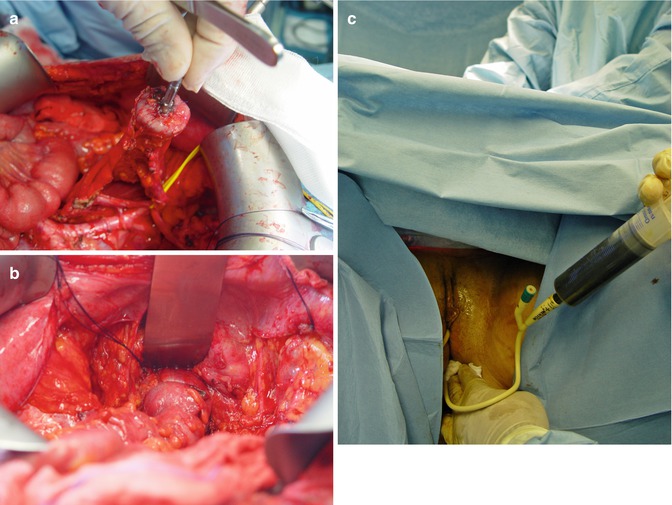

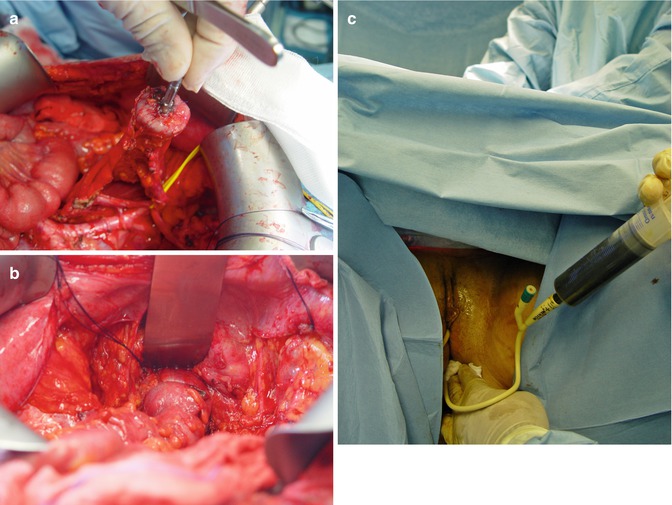

Fig. 38.1

(a, b) Specimen of anterior exenteration, including the uterus and the bladder

These oncologic situations include primary advanced gynecological tumors, but more frequently recurrent pelvic disease, in patients who have already received radiation therapy. In those cases, the preservation of healthy bladder tissue to obtain safe oncological and functional results is very complicated. All these patients will need a urinary diversion. Furthermore, sequelae from radiotherapy such as vesicovaginal fistula, patients with disabling urinary incontinence due to contracted bladder and ureteral stricture are also indications for a urinary reconstruction.

In most of these cases a total infralevator pelvic exenteration is required to eliminate the tumor and the entire urethra needs to be removed. Nevertheless, in a select number of patients undergoing pelvic exenteration the urethra may be preserved. These highly selected cases include patients who undergo a supralevator exenteration where the urethra could be free of any tumor involvement. In these patients, we may consider the option of an orthotopic bladder reconstruction, which spares the patient from the need of a urostomy or external appliance, with the consequent improvement in quality of life.

The goals of urinary diversion after cystectomy have evolved from simple diversion and protection of the renal units to a functioning and anatomic reconstitution as close as possible to the physiologic preoperative state.

Initially, first procedures of reconstruction were done diverting the ureters through the rectum or exteriorizing them directly to the skin.

More recently, the evolution of urinary diversion has developed throughout three different routes: incontinent diversion (conduit); continent cutaneous diversion (pouch); and, most recently, continent urinary diversion to the intact native urethra (neobladder, orthotopic reconstruction).

Urinary Diversion via the Rectum

Ureterosigmoidostomy was the initial procedure used to divert the urine. The ureters were implanted in an anti-reflux fashion into the rectosigmoid colon [4]. The result is an output mixture of urine with feces either throughout the rectum or through a wet stoma. Contraindications for urinary diversion via the rectum are renal failure, pathologic conditions of the rectosigmoid colon such as diverticulosis, completed or planned radiotherapy of the pelvis and an incompetent anal sphincter.

The benefits are the avoidance of a stoma, acceptable continence, and the short duration of the procedure.

Complications include stricture of the ureteral anastomosis, periodic ascending urinary tract infections and severe metabolic acidosis. Incontinence is rare but requires conversion to a different type of urinary diversion. This urinary diversion increases the risk of developing an adenocarcinoma at the site of the ureterointestinal anastomosis [5]. For this reason, the follow-up after should include annual colonoscopy. In the daily basis this approach is rarely used in the gynecologic setting since many of the circumstances for urinary diversion are indicated within a radiated field.

Incontinent Diversion

Ureterocutaneostomy

The exteriorization of the ureters through the skin is the simplest form of urinary diversion, which can be done without performing bowel surgery. This maneuver has a high complications rate, especially ureteral stenosis, obliging patients to catheterize the stoma. Indications for ureterocutaneostomy include palliative treatment, serious comorbidities, reduced life expectancy, previous or intended radiotherapy of the intestine, or other conditions of the bowel (ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease) that require the use of bowel to be avoided [6].

Ileal or Colon Conduit

Since Bricker first described his procedure in 1950, the ileal conduit or Briker’s procedure has been for many years the gold standard for urinary diversions after cystectomy for bladder cancer or after exenteration for gynecologic malignancies [7]. The Bricker’s ileal conduit is still performed by many cancer surgeons around the world. There is a global perception that the ileal conduit is a safer procedure because of its technical simplicity.

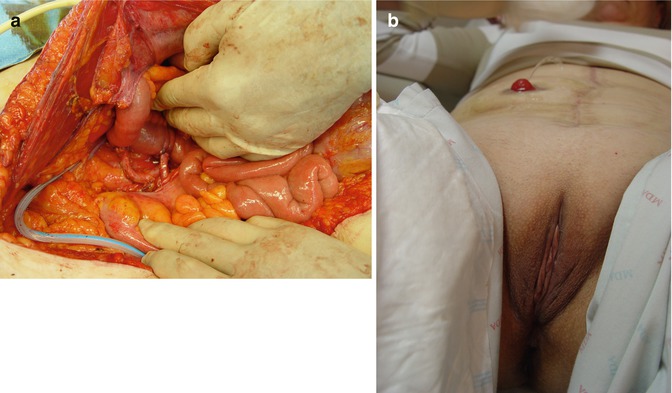

The ileal conduit is still the most commonly used type of urinary diversion (33–63 %). An ileal segment of about 15 cm is detached and laterally brought out as a stoma from the lower abdomen. The ureters are anastomosed into the ileum segment; the urine can flow back into the kidney from the conduit Fig. 38.2a, b. Creating an ileal conduit is technically easier and the procedure takes less time than any other diversion. Furthermore, less of the bowel is resected when an ileal conduit is created. Complications reported in the long term include deterioration in renal function, problems with the stoma, recurring urinary tract infections, ureteral stenosis with development of renal atrophy and calculi. An ileal conduit can be created even in patients with severe renal failure (serum creatinine >2 mg/dL) as well as in those patients who are physically or mentally frail [8].

Fig. 38.2

(a, b) Ileal conduit and urinary stoma

In specific circumstances when the terminal ileum shows severe post radiation changes, a segment of colon, typically transverse colon can be used as conduit.

Continent Diversion (Pouch)

This form of urinary diversion is a continent alternative to the incontinent conduit. However, it is essential for patients to be intellectually and physically able to catheterize the reservoir. Contraindications include renal failure, liver function disorders, and intestinal disorders.

Usually, a reservoir is created from an ileal or ileocecal segment, which is evacuated by self-catheterization through a permanent stoma. The continence mechanism usually relies on a submucosally surrounded appendix [9], an ileum invagination nipple [10], or a Yang-Monti procedure [11].

Complications that are specific to urinary diversion that should be cited include formation of calculi in the reservoir, voiding injuries of the reservoirs subsequent to stoma stenosis and stenosis of the ureteral anastomosis. Incontinence requiring revision surgery is rare, at <5 % [12]. Since the terminal ileum is used to form the reservoirs, patients may develop metabolic acidosis, as well as vitamin B12 deficiency and chlorogenic diarrhea.

Orthotopic Reconstruction (Neobladder)

The rationale for recommending orthotopic neobladder reconstruction includes the fact that sparing the urethra in selected cases might not compromise the oncologic outcome as evidenced by the literature in patients with bladder cancer.

According to a consensus conference on bladder cancer that reviewed the literature on urinary diversion, the orthotopic bladder replacement and continent urinary diversion constituted up to 70 % of all procedures [13]. But this review did not show any superiority of orthotopic neobladder over the other options of transposed intestinal segment surgery in regard of quality of life, and the committee’s decision relied heavily on expert opinion and single-institution retrospective series.

The orthotopic bladder reconstruction is associated with an approximately 80 % rate of urinary continence [14, 15].

However there is virtually no experience in developing the urinary neobladder in gynecologic oncology. There are a number of reasons that explain this fact. First, there are only few situations where is possible to preserve the urethra at the time of a pelvic exenteration without compromising the oncological outcome. Second, most of the indications for pelvic exenteration include patients that have been previously radiated and therefore we must expect worse functional and surgical results than in non-irradiated patients.

With orthotopic urinary reconstruction it is possible to achieve a functional lower urinary tract. But this advantage can be counteracting by an increased rate of complications because of the major technical complexity of these operations. For some authors, complication of neobladders are actually similar or lower than the true rates after conduit formation, in contrast to the popular view that conduits are simple and safe [16].

In gynecologic oncology, there is limited experience with orthotopic reconstruction of the bladder. Ungar and Palfalvi published the first large series of gynecological cancer patients with anterior or total pelvic exenteration reconstructed without external urinary diversion [17]. These authors described their experience with a colonic orthotopic neobladder in 13 women who underwent an exenteration after irradiation for cervical cancer, 30 % of patients suffered a fistula formation, and 70 % achieved adequate daytime continence.

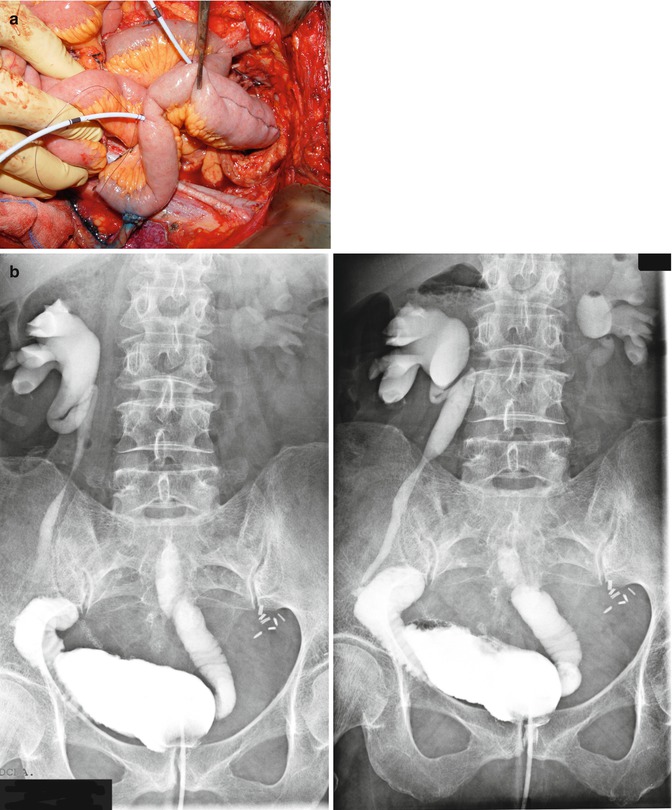

Since 2005, our group has acquired some experience in neobladder after pelvic exenteration. We have developed a modified technique of Fontana’s reservoir, that is create by performing a “Y” shaped ileal neobladder connected to the urethra Fig. 38.3a, b. Up to the present time, 14 cases have been accomplished. The rate urinary continence was 60 %, and the rate of fistula formation was 25 % [18].

Fig. 38.3

(a, b) Ileal “Y” shaped orthotopic neobladder and postoperative cystogram

In summary, nowadays, reconstruction of the urinary tract after pelvic exenteration have allowed many patients to improved their quality of life even after undergoing an incontinent diversion.

38.3 Colorectal Reconstruction

Colorectal resection has become an indispensable tool within the armamentarium of gynecologic oncology surgery. In pelvic exenteration, commonly performed in local recurrence of cervical or endometrial cancer, this procedure is habitually part of the pelvic viscera resection [19, 20]. In ovarian cancer, since the recognition that complete tumor cytoreduction is the best independent prognostic factor for survival, this procedure is performed more often as part of the “en bloc” removal of the pelvic disease [21].

In fact as can be observed in the literature, one out three patients with advanced ovarian cancer needs a colorectal resection to obtain complete exeresis of the tumor [22].

The development of specific devices for mechanical anastomosis have allowed an easier, safer and faster procedure even more important for a low or very low anastomosis that would help for the restoration of the intestinal continuity as well as its natural function, both important in these woman’s quality of life. Although colorectal surgeons developed these techniques, it is important to emphasize the specific behavior of gynecologic malignancies and their previous treatments.

Performing the Anastomosis

Care must be taken to ensure that the anterior longitudinal muscle layer of the rectum is included in the anastomosis because it tends to be cut during the dissection and retract distally. It is of particular importance that low rectal anastomosis is performed without tension. This will usually require mobilization of the splenic flexure. Although the anastomosis can be hand sewn or stapled, automatic stapling devices make the procedure easier to perform and are probably superior to the hand-sewn techniques in terms of outcome.

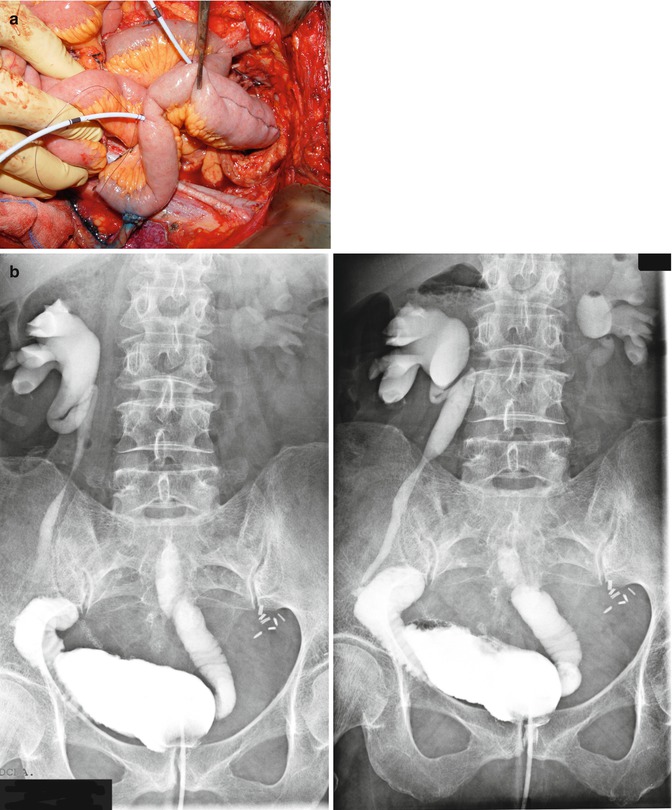

Out of the several techniques described, the most frequently used is the end-to-end anastomosis with the circular stapling device inserted through the anus. The largest circular stapler that will fit the bowel segments should be used because of the proclivity of these anastomoses to develop stenosis (Fig. 38.4a–c).

Fig. 38.4

(a–c) Colorectal anastomosis: introducing the trocar, firing the device and checking the anastomosis with methylene blue

After completing the anastomosis, it is checked for viability and integrity. First, the tissue donuts around the cartridge shaft are checked for defects. Second, the proximal bowel segment to the anastomosis is occluded, and the anastomosis distended by methylene blue. Water can be placed in the pelvis and air placed via the rectum to check for air leaks. If any leakage is presented, the defect in the staple line is reinforced with some sutures. If the leak is inaccessible for repair, the anastomosis must be redone or a proximal diverting stoma is performed. The anastomosis can be wrapped in an omental pedicle if available but no definitive advantage has been demonstrated.

Other options for rectal anastomoses include the end-to-side EEA, functional end-to-end GIA, and side-to-side GIA with the bowel ends overlapping. It is believed that the end-to side and side-to-side anastomoses have a somewhat better blood supply. Furthermore, the end-to-side and anastomoses and functional end-to-end anastomoses sometimes conform better to the natural curve in the sigmoid colon. Patients with low colorectal anastomosis (less than 7 cm from the anal verge) commonly suffer from frequent stools, urgency, and soiling. The colonic reservoir or J-pouch provides a reservoir when all or most of the rectum has been removed but not all the sigmoid colon [23].

Predisposing patient factors that have been reported to increase the risk for complications from bowel surgery are advanced age, gender, chronic steroid use, diabetes mellitus, arteriosclerosis, chronic inflammatory bowel disease, prior radiation therapy or chemotherapy, extensive adhesions, poor nutrition (low serum albumin), anemia, renal failure, malignancy, bowel obstruction before surgery, sepsis (abscess, peritonitis), surgery duration, number of blood units transfused, and hypotension.

The most important common complications of the bowel surgery are anastomotic leak, stenosis, and hemorrhage [24].

Technical factors that might be related to the risk for complications include: failure to observe the general principles of bowel surgery (i.e., avoiding tension and ischemia, ensuring good hemostasis, making an adequate-size anastomotic ring, and checking the integrity of the anastomosis; the specific technique of the anastomosis (i.e., stapled or hand sewn, single or double layer) and the bowel involved in the anastomosis (i.e., small bowel, colon or rectum, intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal) [25].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree