| 17 | Rare Diseases and Disorders |

Extrinsic Compression (Stenosis)

Extrinsic narrowing of the colon lumen can be caused by retro-peritoneal tumors (kidneys, adrenal glands, pancreas, ovaries, uterine and cervical carcinoma or lymphoma) or by retroperitoneal abscesses (Fig. 17.1). Though peritoneal carcinoma often causes adhesions—which especially make endoscope passage in the sigmoid difficult because of lacking compressibility of the abdomen (“splinting technique”)—it does not cause narrowing of actual lumen.

A small-caliber therapeutic colonoscope is usually necessary to achieve total colonoscopy if there is stenosis of the bowel. Additional use of a colon contrast enema or virtual computed tomography (CT) imaging of the colon is rarely necessary for examination.

Postoperative Strictures and Suture Granulomas

Postoperative strictures. Postoperative strictures are commonly observed in the anastomosed region of the lower rectum after rectal resection. They are occasionally the result of dehiscence after resection of very low rectal carcinomas. Therapy with balloon dilation can help dilate the stricture. Dilation should be performed step-by-step in intervals of three to four days (balloon diameter: 15-25 mm). Intestinal resection in Crohn disease can also lead to inflammatory stenosis or scarring (Fig. 17.2), the latter of which is endoscopically treatable with balloon dilation, if a shorter bowel segment is affected.

Suture granulomas. The surface of the often-granulated mucosa is smooth so that it is unlikely that a suture granuloma will be mistaken for a sessile polyp or early carcinoma, even based on visible appearances alone. If there is any doubt, a biopsy should be performed. Sometimes suture remnants are visible (Fig. 17.3).

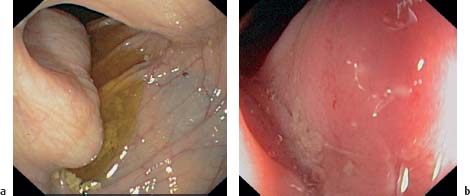

Fig. 17.1 Extrinsic compression (stenosis).

a Compression in ascending colon from retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

b Compression in ascending colon due to kidney tumor; mucosa is reddened.

Fig. 17.2 Postoperative stricture. Extreme narrowing of ileocolonic anastomosis in Crohn ileitis.

Fig. 17.3 Suture granulomas. Three dark suture granulomas at the anastomosis after sigmoid resection (not clinically relevant).

Lumen Dilation and Pseudo-obstruction

Definition

Definition

Megacolon. The term megacolon describes both congenital and acquired forms of colon dilation. In all younger patients with megacolon, the possibility of Hirschsprung disease should be excluded. Hirschsprung disease manifests in the first years of life caused by absence of parasympathetic ganglion cells in my-enteric (Auerbach) and submucosal (Meissner) plexuses in the rectum. The absence of ganglion cells results in constipation and bowel obstruction.

Clinical Picture

Clinical Picture

Congenital megacolon (Hirschsprung disease). Congenital megacolon manifests from birth as persistent constipation. If the aganglionic intestinal segment is short, it is usually possible to empty the bowel using enemas and laxatives. If the affected segment is longer, there is complete blockage of the bowels and the infant will die without early surgical intervention.

Fig. 17.4 Dilation of colon: pseudo-obstruction. Radiograph image shows considerable colon distention, especially in the ascending colon, and spare or lacking haustration. Increased vulnerability of the mucosa and risk of perforation (courtesy of Dr. Volker Remplik, Institute for Radiology, Augsburg Clinic).

Acquired megacolon (secondary). Acquired (secondary) megacolon develops at any age as a result of stenosis in the rectum or sigmoid caused by a tumor, scarring, or spasms related to chronic anal fissures.

Functional megacolon (actual pseudo-obstruction). In functional megacolon (no anatomical cause), the colon is dilated up to the rectum. Unlike in Hirschsprung disease the rectum is filled with stool. Functional megacolon can be constitutional and may be familial. Distention usually affects the entire sigmoid colon, though it can also involve the whole colon.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Fig. 17.5 Decompression of colon distention by means of a decompression tube. Very large gallstone presenting as a rounded calcification at the upper left edge of the image (courtesy of Dr. Volker Remplik, Institute for Radiology, Augsburg Clinic).

Additional examinations. An abdominal radiograph can demonstrate the exact extent of bowel distention in the acute phase as well as decompression after placement of a decompression tube (Figs. 17.4, 17.5).

In Hirschsprung disease, manometry can be used to detect defective relaxation of the internal rectal sphincter. Disease can be eliminated by resection of the aganglionic rectal segment.

Radiographic contrast studies are essential in all forms of megacolon for further treatment planning.

Differential diagnosis. Hormonal and medication-induced causes must be excluded. These include: hypothyroidism, acromegaly, diseases of the brain and spinal cord, morphine abuse, vitamin B1 deficiency, acute potassium deficiency, and anti-cholinergic use.

Treatment

Treatment

In Hirschsprung disease, resection of the aganglionic rectal segment is unavoidable. Other forms of megacolon (“slow transit”) are treated conservatively.

If there is massive dilation with lacking intestinal tone and distention of the transverse diameter exceeding six centimeters, placement of a decompression tube (e.g., Cook, Wilson–Cook Medical Inc., Winston–Salem, NC, USA) using a long guidewire inserted through the endoscope (4.80m long, 0.035 inches wide) is necessary. Decompression occurs immediately (Fig. 17.5). After carefully building up food intake, beginning with tea and plain toasted bread, after a few days the patient may have foods higher in fiber along with ample amounts of water. In some cases, high fiber bulk laxatives (Indian Plantago, etc.) must be prescribed. Laxatives should only be used in severe cases. Osmotic laxatives (magnesium sulfate, lactulose, lactitol, macrogol) have limited side effects. Macrogol (polyethylene glycol) does not cause gas and thus does not increase bowel distention.

If the patient has obstructive constipation (e.g., rectocele) surgical intervention is the only option.

Fig. 17.6 Segmental hemorrhagic colitis. Forty-year-old patient with highly acute lower abdominal pain (rightsided) five days after taking amoxicillin. Mucosal hemorrhaging in ascending colon.

Surveillance

Surveillance

Follow-up surveillance should be performed every 4-6 months to monitor the continued effectiveness of treatment and, if necessary, treatment should be adjusted. Attention should be paid to regularity of bowel movements.

Acute Segmental Hemorrhagic Colitis

Definition

Definition

Acute segmental hemorrhagic colitis presents clinically with acute lower and middle abdominal pain (usually rightsided) and hematochezia.

Clinical Picture

Clinical Picture

Onset is sudden and occurs about four to five days after oral use of penicillin or amoxicillin. Typical signs include spontaneous pain and considerable local tenderness in the right abdomen. Lab tests show increased levels of CRP (C-reactive protein) and leukocytes. Fever is not present or is only mild; diarrhea is not typical.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Sonography reveals lacking layering of the intestinal wall in the affected segment of the thickened ascending colon. The thickened colon wall is asymmetrical, unlike in pseudomembranous colitis, where the wall is symmetrical.

Differential diagnoses. Differential diagnosis should exclude Yersinia enterocolitis, Campylobacter jejuni, EHEC (Entero-hemorrhagic escherichia coli) or Klebsiella, all of which are accompanied by pronounced and sometimes watery diarrhea. In immunosuppressed patients cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis (Fig. 17.7) can be excluded with biopsy (CMV PCR); the chief symptom of CMV colitis is hematochezia.

Fig. 17.7 CMV colitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The colon is distended and elongated. Stagnation of bowel contents can lead to secondary colitis.

The colon is distended and elongated. Stagnation of bowel contents can lead to secondary colitis.

Colonoscopy shows typical hemorrhagic mucosal changes in the ascending colon (

Colonoscopy shows typical hemorrhagic mucosal changes in the ascending colon (