Fig. 11.1

2.5× power-loupes and fiberoptic coaxial headlight and battery

Fig. 11.2

Designed self-retractor

11.3 Position

The patient is placed in supine position, with the pubis centered over the break of the table, flexed, to elevate the pelvis and facilitate exposure. A 25–30° Trendelenburg position also improves vision and reduce blood loss on the venous dorsal complex approach [4].

11.4 Incision, Exposure and Lymphadenectomy

A 16-Charrière (Ch) Foley catheter is inserted into the bladder and the balloon inflated with 10–15 cc of water. An 8–10 cm vertical midline incision made from 2 cm above the symphysis to approximately below the umbilicus provides very good exposition. The access to the Retzius space is done by opening the anterior fascia down to the pubis, splitting the rectus muscles in the midline, lifting the semilunar line and freeing the peritoneum from the internal inguinal rings and the external iliac vessels. Prostate cancer patients who are at high and intermediate risk for lymph node involvement should be submitted to extensive resection of the internal iliac lymph nodes [5–8]. Lymphadenectomy is made preferentially before the radical prostatectomy. The limits of dissection are: laterally, the upper limit of the external iliac vein and artery; caudally, the femoral canal; proximally, the bifurcation of the common iliac artery; medially, the lateral wall of the bladder; and inferiorly, the floor of the obturador fossa and the internal iliac vessels [9, 10]. It is done with the table in side-position (30°) and the aid of a Leriche spatula. Lymphatic and small vessels are ligated with small clips.

11.5 Retractor Placement

The self-retractor is placed with the Richardson type blade to fix the bladder underneath it. The assistant helps with a scissor in an upside down position.

11.6 Incision in Endopelvic Fascia

After lymph node dissection, all fatty tissue covering the endopelvic fascia and surrounding superficial Santorini’s complex is removed. The outer layer of the endopelvic fascia is incised medial to the tendinous arc extending posteriorly with gentle lateral separation of the levator muscle with scissors and the aid of a peanut. It is essential to open, very well and posteriorly, this plan for freeing completely both sides of the prostate, facilitating the later approach to lateral pedicles. The endopelvic fascia is then incised anteriorly up to the puboprostatic ligaments. This is done in both sides.

11.7 Division of Puboprostatic Ligaments

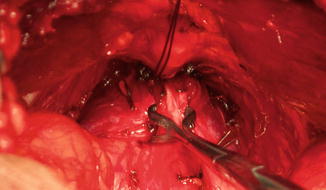

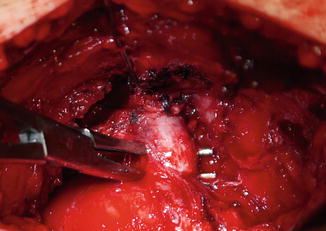

The superficial dorsal venous complex is situated between these ligaments anteriorly and the deep dorsal venous complex posteriorly. Pushing the anterior surface of the prostate backwards allows the exposition of these ligaments, facilitating its dissection and section with scissors. A right-angled forceps passing behind them can be used. Care must be taken not to hit veins that are most of the time just behind (Fig. 11.3). This maneuver allows the release of the prostate from the pubic symphysis.

Fig. 11.3

Puboprostatic ligament

11.8 Bunching and Division of the Dorsal Venous Complex

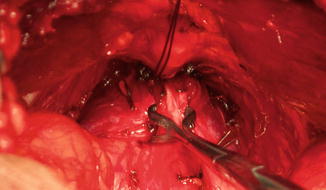

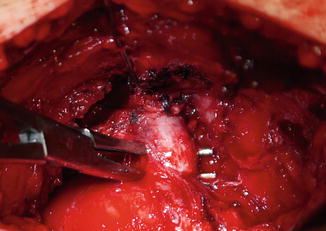

Opening laterally the second layer of the endopelvic fascia and the periprostatic fascia, from the apex to the bladder neck, will allow the preservation of the neurovascular bundles (NVB). These are rolled and separated laterally with the help of a peanut. This facilitates the bunching, with a Babcock clamp, of the dorsal venous complex that includes the ventral portions of the endopelvic and periprostatic fascia (Fig. 11.4). Its ligation is made with one 1-polyglactine absorbable suture over the prostate apex and another near the bladder neck. The transection of the Santorini’s plexus just above the prostato-urethral junction is done with scalpel or scissors.

Fig. 11.4

Bunching of the dorsal venous complex with separation of the NVB from the lateral surface of the prostate

11.9 Apical Prostatic Dissection

The prostatic apex is approached by careful dissection along the ventral surface of the prostate towards the membranous urethra. Perfect view of this step can be achieved by gently pulling the prostate and the intraprostatic urethra upwards with a Gil-Vernet retractor. The advantage of open surgery is enabling the use of the index finger to better isolate the apex thus avoiding positive surgical margins at this difficult step. Urethra is dissected laterally by opening scissors longitudinally, achieving a maximal urethral length and an integral preservation of striated sphincter [11]. If necessary, bleeding from the Santorini’s plexus is controlled by an eight figure horizontal 0-polyglactine absorbable suture, encircling the plexus.

11.10 Release of Neurovascular Bundles Starting Backwards at the Urethroprostatic Angle

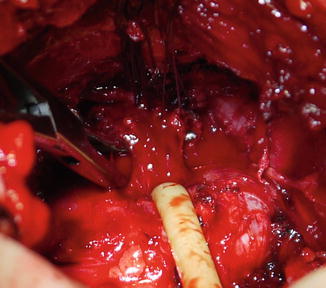

At this time it is possible to continue the NVB preservation backwards by clipping the perforating vessels and pushing them down. The prostatic apex is now completely released, enabling a full view of the membranous urethra (Fig. 11.5).

Fig. 11.5

Apical prostatic dissection

11.11 Division of Anterior Urethra and Setting the Urethral Sutures

With the 16-Ch Foley catheter still in place it is possible to transect the anterior and lateral surfaces of the urethra with the scalpel. The catheter is pulled cut and its stub hold by the assistant with a straight Kelly forceps but without making significant traction on the prostate. With the aid of an in-and-out movement of a Mercier catheter, four 2–0 double semicircular (5/8) needle polyglactin sutures are placed. This is done without cutting the posterior surface of the urethra, thereby preventing its retraction down to the pelvic floor. This step allows the visualization of all the stub length and the passage of the sutures merely in the urethra, not picking the levator ani muscle. Posterior and anterior sutures are placed in an inside-out movement, at 5 and 7 o’clock position, medial to the NVB and at 2 and 11, respectively. It is taken approximately 10 mm of the urethra length. The sutures are individually attached to the surgical drapes with mosquito forceps for later vesicourethral anastomosis. These four sutures are sufficient for a good anastomosis.

11.12 Division of the Posterior Urethra and Rectourethralis Muscle

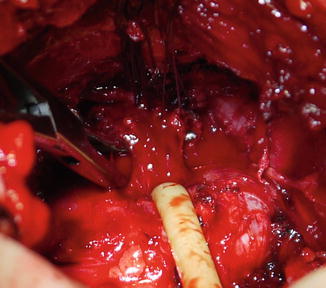

The division of the posterior urethra is made with the scalpel at the level of the distal verumontanum after passing underneath it a right-angled forceps (Fig. 11.6). Once the urethra is sectioned, the rectourethralis muscle becomes evident. It is variable in strength and thickness. Sometimes muscle fibers are sparse and index finger easily recognizes the right plane between the prostate and the rectum. Sometimes it is a real muscular plate that needs to be incised and dissected with scissors.

Fig. 11.6

Division of the posterior urethra and rectourethralis muscle

11.13 Posterior Release and Ligation of Lateral Prostatic Pedicles

The index finger can easily reach up the seminal vesicles. In non-nerve sparing procedure, the NVB are completely resected and ligations with 2-0 polyglactin sutures are made close to the rectum. In the NVB preservation, small clips are used on the very little complexes of perforating vessels and nerve fibers close to the prostate. Electrocautery is never used. These maneuvers are done by ambidextrous technique with index fingertips positioned posterolaterally for constant haptic feedback [12]. Dissection continues up to the lateral surface of the seminal vesicles. In selected patients with smaller unilateral and non-apical cT3a prostate cancer, a contralateral nerve-sparing dissection can be done. Most of the authors, such as Sokoloff and Brendler [13], consider that cT3b tumors and palpable lesion at the apex are absolute contraindications for the nerve-sparing technique.

11.14 Dissection of the Seminal Vesicles and Vas Deferens

The Denonvillier’s fascia is horizontally sharply incised at the posterior surface of the transition between prostate and the insertion of seminal vesicles and vas deferens, allowing the access to these structures. The vas deferens are dissected, isolated, clipped and cut. The seminal vesicles undergo the same dissection, down to the tip where vessels are clipped, without causing any trauma by squeezing, pulling or tearing to the adjacent plexus running along their dorsolateral aspect. Patients at very low risk of seminal vesicle invasion can be identified with high accuracy with an equally nomogram [14]. Zlotta et al. concluded that “complete resection of seminal vesicle may not be oncologically necessary in all patients when PSA levels are below 10 ng/ml.” Their data showed that patients with biopsy Gleason scores <7 and less than 50 % of biopsies with prostate cancer involvement, have a low probability of SV invasion [15]. Other studies showed that patients submitted to seminal vesicle sparing technique can have a beneficial impact on erectile [16] and urinary function [17]. In these cases, we do the preservation, transecting them and leaving its tips intact. Prostate at this time is completely mobilized posteriorly and laterally up to the bladder neck.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree