Jennifer Blanchard

Patients infected with HIV are predisposed to a variety of infectious, inflammatory, and neoplastic pulmonary diseases. Over the past decade, significant changes in the spectrum of HIV-related pulmonary complications have been observed after the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART—a combination of protease inhibitors taken with reverse transcriptase inhibitors) and the widespread use of effective prophylaxis against opportunistic infection. Moreover, the population characteristics and risk factors associated with HIV infection have evolved; AIDS is observed increasingly in women, children, and intravenous drug abusers. Homosexual and bisexual men still represent the majority of cases of HIV, but their percentage is decreasing in the United States.

The most prevalent opportunistic infection in patients infected with HIV is Pneumocystis pneumonia, which is an AIDS-defining illness. It has been officially renamed P. jirovecii pneumonia, but is still called PCP (for “PneumoCystis pneumonia”) in the infectious disease community. Since the advent of HAART, the incidence has declined. The mode of transmission is not entirely known. Person-to-person airborne transmission is possible, but an environmental exposure is the most likely mode of transmission. Respiratory isolation of PCP-infected patients is not necessary. The risk of infection with PCP in HIV-infected patients increases sharply once the CD4 count drops below 200 cells/mm or there is a history of oropharyngeal candidiasis. In addition, the annual risk of recurrence after an episode of PCP is greater than 60%. For these reasons, HIV-infected patients with CD4 counts less than 200 or with a prior history of PCP should receive chemoprophylaxis. Primary or secondary prophylaxis can be discontinued in patients who have a response to HAART vigorous enough to raise the CD4 count to more than 200 for a period of 3 or more months. However, prophylaxis should be reinstituted if the CD4 cell count drops to less than 200. Drugs recommended for the prophylaxis are listed in Table 61-1.

The presentation of PCP in AIDS patients is usually indolent, with the onset of a nonproductive cough, progressive dyspnea, and fever over days to weeks. This is in contrast to the abrupt onset of symptoms typically observed in cancer patients. The physical examination is dominated by tachypnea and tachycardia; auscultatory findings can range from none to diffuse rales and rhonchi. Symptoms of local inflammation are distinctly absent (i.e., pleurisy, productive cough), and the presence of these should raise the possibility of an alternative diagnosis. Symptoms may be mild and permit outpatient management with oral therapy; however, severe hypoxemia mandates hospital admission and intravenous therapy.

Laboratory abnormalities often are nonspecific, revealing lymphopenia and anemia. Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is almost always elevated, although it probably reflects the inflammation of the lung parenchyma and is not a specific marker for PCP. The serum LDH, while nonspecific, is useful as a prognostic indicator, that is, a higher LDH signals a higher burden of disease. The chest radiograph is abnormal in 80% to 90% of cases and typically displays bilateral perihilar interstitial infiltrates that can progress to diffuse and homogenous opacities. Less common radiographic findings include solitary or multiple nodules, upper-lobe infiltrates in patients receiving inhaled pentamidine, pneumatoceles, and pneumothorax. Although the chest radiograph may be normal in 5% to 10% of patients, high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) commonly discloses extensive ground-glass attenuation or cystic lesions. An HRCT with normal findings essentially rules out the diagnosis of PCP. Pleural effusions and thoracic lymphadenopathy are suggestive of other (or coexisting) diagnoses such as bacterial pneumonia, mycobacterial disease, or malignancy.

The arterial Po2 is abnormal in most cases and is a key prognostic indicator. Patients presenting with near-normal oxygenation generally do well with treatment. An abnormal carbon monoxide diffusing capacity, oxygen desaturation during exercise, and an abnormal gallium lung scan are sensitive but nonspecific for PCP infection.

Medications for PCP Prophylaxis | ||

Drug | Dose | Comments |

TMP-SMX | One double-strength tablet daily | Most effective and most widely recommended |

| One single-strength tablet daily | Short-term intolerance is common and prophylaxis can frequently be continued |

Pentamidine | 300 mg monthly | Given by inhalation |

Dapsone | 100 mg daily | Ensure patient does not have G6PD deficiency |

Atovaquone | 1,500 mg daily | Give with meals to improve absorption |

Because the organism cannot be cultured, microscopic examination of an appropriate specimen is required to make the diagnosis. Patients with AIDS and PCP have significantly more organisms in their lungs than PCP patients without AIDS. Because of the higher organism burden, induced sputum has a diagnostic yield of 50% to 90% in AIDS patients and should be the initial diagnostic procedure if PCP is suspected. If induced sputum is either negative or not available, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid obtained by fiberoptic bronchoscopy has a 90% to 95% sensitivity for PCP in the AIDS population. Transbronchial or open-lung biopsy is seldom needed. However, with an atypical presentation (e.g., focal disease), other diseases become more likely and transbronchial biopsy should be considered. The clinician should be aware that the (presumably dead) P. jirovecii cysts can persist for weeks to months after successful treatment, so a positive result on repeat testing does not necessarily indicate relapse.

Trophic forms of Pneumocystis can be detected with modified Papanicolaou or Wright–Giemsa stain. The cysts can be stained with Gomori methenamine silver, toluidine blue O, or calcofluor white. Immunohistochemical stains detect both the trophic forms and cysts and have higher sensitivity and specificity in induced sputum samples than conventional tinctorial stains. However, BAL fluid usually contains such a high density of organisms that immunohistochemistry is unnecessary.

Nucleic acid amplification using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on respiratory specimens has greater sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of PCP than conventional staining. In patients with a positive PCR but a negative smear, treatment is recommended if the patient is immunosuppressed. PCR testing of serum samples has not yet been shown to be useful.

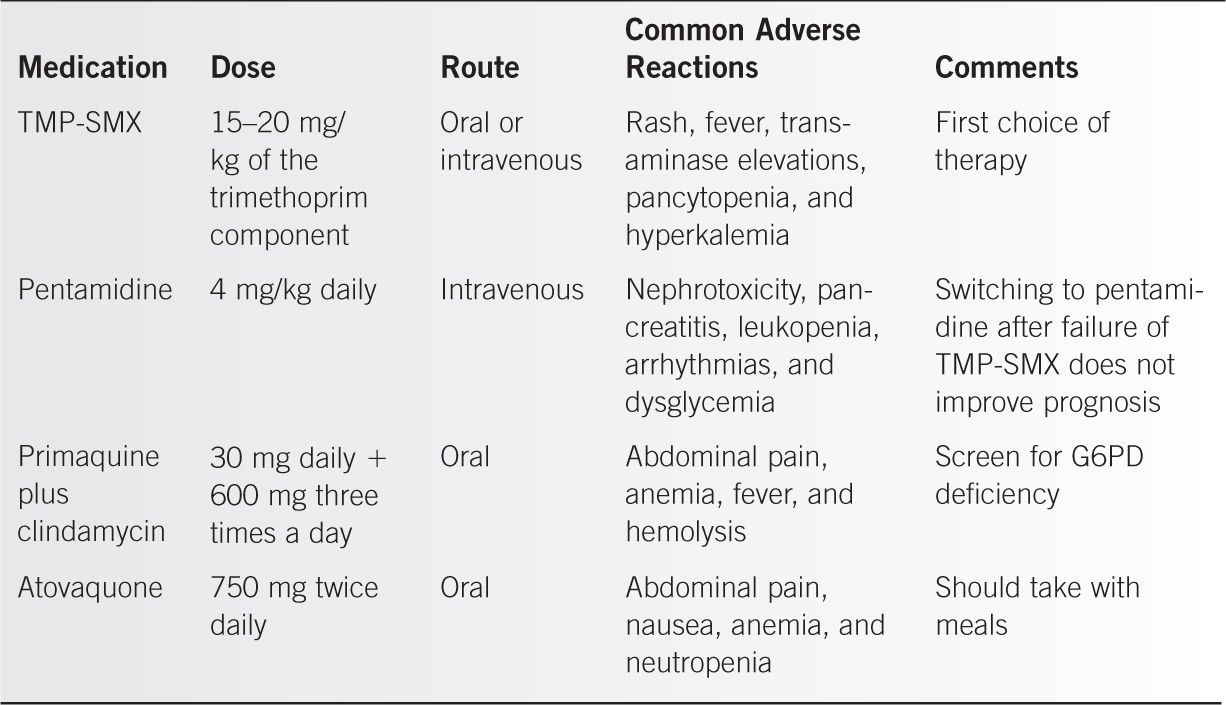

Those with mild cases of PCP can be treated as outpatients with close follow-up. Hospitalization is usually indicated when the alveolar–arterial oxygen gradient (P[A–a]o2) is greater than 35 mmHg or the chest radiograph is clearly abnormal. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) is the preferred form of therapy. In moderate to severe disease, parenteral therapy initially is preferred. Drugs used in the treatment of PCP are listed in Table 61-2.

Administration of adjunctive corticosteroids is indicated in patients with a Pao2 < 70 mmHg or P(A–a)o2 > 35 mmHg. A recommended treatment regimen is prednisone given orally at a dose of 40 mg twice daily for 5 days, then 40 mg daily on days 6 through 11, and then 20 mg daily on days 12 through 21.

Medications Used in the Treatment of PCP |

With the widespread use of sulfa drugs for prophylaxis and treatment of PCP, there is some concern about mutations in the dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS) gene of P. carinii. Some investigators have reported a correlation between prior sulfa prophylaxis and the occurrence of this mutation; however, the clinical significance of this mutation is still poorly understood. Failure of sulfa-based treatment is considered so rare that patients with sulfa allergies failing alternative therapies are desensitized to sulfa and treated with high-dose TMP-SMX at our institution.

Pneumothoraces in the setting of PCP can lead to prolonged air leaks and long-term morbidity. Conservative management is associated with high failure rates and prolonged hospitalization. Needle drainage, tube thoracostomy, Heimlich valve drainage, pleurodesis, pleurectomy, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, and thoracotomy may be needed. The reported success rates of tube thoracostomy in the evacuation of pneumothorax are variable. Heimlich valve drainage has been shown to facilitate earlier discharge from acute-care facilities. Surgery is needed if tube thoracostomy does not resolve the pneumothorax. The reported recurrence rates of spontaneous pneumothorax in AIDS are high (11%–60%), with pneumothorax in PCP being an independent predictor of mortality.

The introduction of HAART in patients may be complicated by the Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome (IRIS). This syndrome, first described in patients with tuberculosis, has been reported with every opportunistic infection as well as hepatitis B and C. For example, patients with PCP can develop a pneumonic syndrome after effective PCP treatment and subsequent HAART initiation. No pathogens are identified on bronchoscopy, and the BAL CD4/CD8 ratio is much higher than in the initial illness. The evidence suggests that an influx of CD4 cells may be responsible for the syndrome. It can become severe enough to cause respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Bacterial pneumonia remains a common complication of HIV infection. Streptococcus pneumonia and Haemophilus influenzae

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree