This article provides an update on the surgical technique and long-term outcome of the full-length autologous rectus fascial sling in the treatment of women with sphincteric incontinence. The autologous fascial puovaginal sling remains the gold standard against which other surgeries for treating sphincteric incontinence should be compared. The authors have demonstrated that this procedure can be performed in a reproducible fashion with minimal morbidity.

A plethora of surgical techniques has been devised for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence, but over the past decade, two approaches have emerged as the gold standards—the Burch colposuspension and the pubovaginal sling. Historically, use of the pubovaginal sling had been reserved for women with complicated, severe, or recurrent sphincteric incontinence, but has been advocated for almost all types of sphincteric incontinence (simple and complicated). Fueled by a stampede of commercial innovations in sling materials, allograft and synthetic slings have become the most commonly used techniques for treating sphincteric incontinence in women. There is little doubt that some kind of allograft or synthetic sling will replace the autologous fascial sling as the gold-standard treatment. This article provides an update on the surgical technique and long-term outcome of the full-length autologous rectus fascial sling in the treatment of women with sphincteric incontinence.

Operative technique

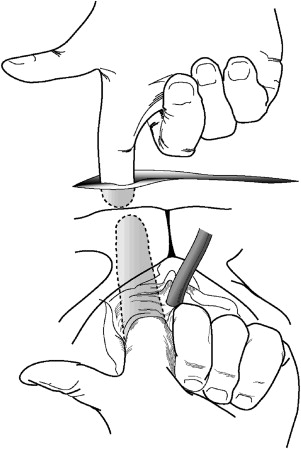

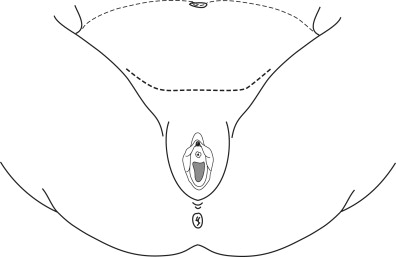

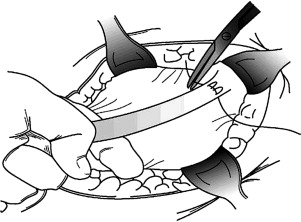

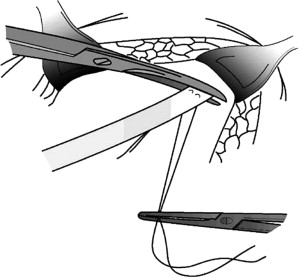

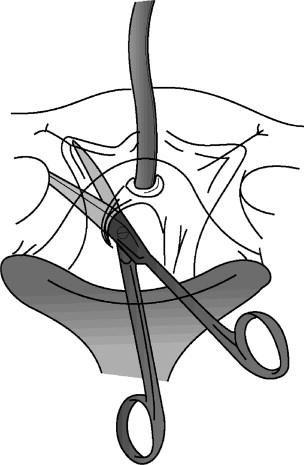

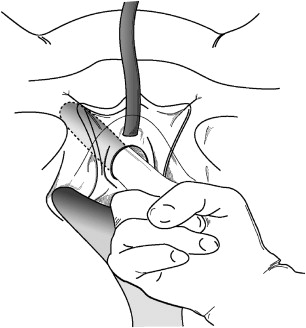

The procedure is performed in the dorsal lithotomy position. For most patients, a short (6–8 cm) transverse incision is made just above the pubis below the pubic hairline ( Fig. 1 ). In obese patients, a larger incision may be necessary. The incision is carried down to the surface of the rectus fascia, which is dissected free of subcutaneous tissue. Two parallel horizontal incisions are made 2 cm apart in the midline of the rectus fascia about 2 cm above the pubis ( Fig. 2 ). Using Mayo scissors, the incisions are extended superolaterally toward the iliac crest following the direction of the fascial fibers. The wound edges are retracted laterally on either side to permit a sling of about 16 cm to be obtained. The undersurface of the fascia is freed from muscle and scar, and each end of the fascia is secured with a 2:0 permanent monofilament suture using a running horizontal mattress placed at right angles to the direction of the fascial fibers ( Fig. 3 ). The fascial strip is excised ( Fig. 4 ) and placed in a basin of saline. The wound is packed temporarily with saline-soaked sponges, and attention is turned to the vagina.

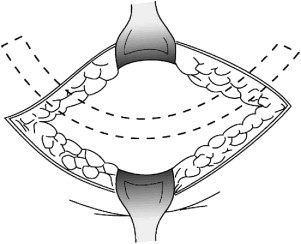

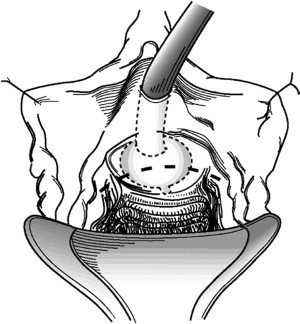

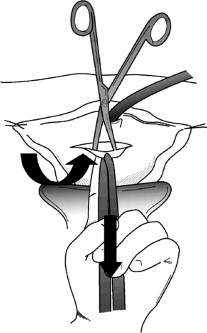

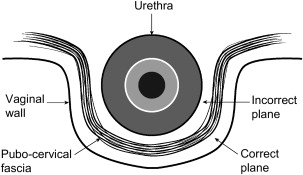

A weighted vaginal retractor is placed in the vagina, and a Foley catheter is inserted into the urethra. The labia are retracted with sutures. The vesical neck is identified by placing gentle traction on the Foley catheter and palpating the balloon, and a gently curved horizontal incision is made in the anterior vaginal wall. The apex of the curve is over the vesical neck and about 2 cm proximal to the palpable distal edge of the balloon ( Fig. 5 ). This incision should be made superficial to the pubocervical fascia. To accomplish this task, an Allis clamp is placed on the cranial edge of the vaginal incision in the midline. The clamp is grasped by the surgeon’s left hand, and caudad traction is applied while the left index finger pushes upward ( Fig. 6 ). A plane is created that is superficial to the pubocervical fascia through dissection with Metzenbaum scissors at an angle of 60° to 90° to the undersurface of the vaginal incision. The proper plane is identified by noting the characteristic shiny white appearance of the undersurface of the anterior vaginal wall. A small posterior vaginal flap is made for a distance of about 2 cm, just wide enough to accept the sling Fig. 7 depicts the anatomic relationships between the vaginal wall, pubocervical fascia, and lower urinary tract.

The lateral edges of the wound are grasped with Allis clamps and retracted laterally. The dissection continues just beneath the vaginal epithelium, and Metzenbaum scissors are pointed in the direction of the patient’s ipsilateral shoulder ( Fig. 8 ) using the index finger ( Fig. 9 ) until the periostium of the pubis is palpable. During this part of the dissection, it is important to stay as far lateral as possible to insure that the urethra, bladder, and ureters are not injured. This step is accomplished by pointing the concavity of the scissors laterally and by exerting constant lateral pressure with the tips of the scissors against the undersurface of the vaginal epithelium. Once the periostium is reached, the endopelvic fascia is perforated, and the retropubic space is entered. The bladder neck and proximal urethra bluntly are dissected free of their attachments to the vaginal and pelvic walls.

A Kocher clamp is placed on the inferior edge of the rectus fascia in the midline, and the fascia is pulled upward. The left index finger is reinserted into the vaginal wound, retracting the vesical neck and bladder medially. The tip of the finger palpates the right index finger, which is inserted just beneath the inferior leaf of the rectus fascia and guided along the undersurface of the pubis until it meets the left index finger from the vaginal wound ( Fig. 10 ). A long curved clamp (DeBakey) is inserted into the incision and directed to the undersurface of the pubis. The tip of the clamp is pressed against the periostium and directed toward the left index finger, which retracts the vesical neck and bladder medially ( Fig. 11 ). At all times, the left index finger is kept between the tip of the clamp and the bladder and urethra, protecting these structures from injury. In this fashion, the clamp is guided into the vaginal wound. When the tip of the clamp is visible in the vaginal wound, the long suture, which is attached to the fascial graft, is grasped and pulled into the abdominal wound ( Fig. 12 ). The procedure is repeated on the other side.