History and current status: Obtain standard background information regarding such areas as the prospective donor’s educational level, living situation, cultural background, religious beliefs and practices, significant relationships, family psychosocial history, employment, lifestyle, community activities, legal offense history, and citizenship. |

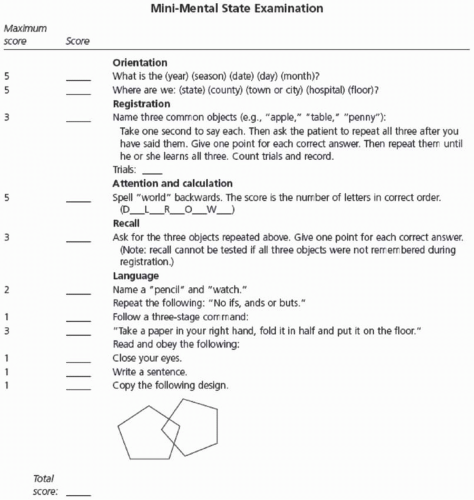

Capacity: Ensure that the prospective donor’s cognitive status and capacity to comprehend information are not compromised and do not interfere with judgment; determine risk for exploitation. |

Psychological status: Establish the presence or absence of current and prior psychiatric disorder, including but not limited to mood, anxiety, substance use, and personality disorders. Review current or prior therapeutic interventions (counseling, medications); physical, psychological, or sexual abuse; current stressors (e.g., relationships, home, work); recent losses; and chronic pain management. Assess repertoire of coping skills to manage previous life or health-related stressors. |

Relationship with the transplant candidate: Review the nature and degree of closeness (if any) to the recipient, such as how the relationship developed and whether the transplant would impose expectations or perceived obligations on the part of either the donor or the recipient. |

Motivation: Explore the rationale and reasoning for volunteering to donate, that is, the “voluntariness,” including whether donation would be consistent with past behaviors, apparent values, beliefs, moral obligations, or lifestyle, and whether it would be free of coercion, inducements, ambivalence, impulsivity, or ulterior motives (e.g., to atone or gain approval, to stabilize self-image, to remedy psychological malady). |

Donor knowledge, understanding, and preparation: Explore the prospective donor’s awareness of any potential short- and long-term risks for surgical complications and health outcomes, both for the donor and the transplant candidate; recovery and recuperation time; availability of alternative treatments for the transplant candidate; and financial ramifications (including possible insurance risk). Determine that the donor understands that data on long-term donor health and psychosocial outcomes continue to be sparse. Assess the prospective donor’s understanding, acceptance, and respect for the specific donor protocol, including willingness to accept potential lack of communication from the recipient and willingness to undergo future donor follow-up. |

Social support: Evaluate significant other, familial, social, and employer support networks available to the prospective donor on an ongoing basis as well as during the donor’s recovery from surgery. |

Financial suitability: Determine whether the prospective donor is financially stable and free of financial hardship; has resources available to cover financial obligations for expected and unexpected donation-related expenses; is able to withstand time away from work or established role, including unplanned extended recovery time; and has disability and health insurance. |

From Dew MA, Jacobs CL, Jowsey SG, et al. Guidelines for the psychosocial evaluation of living unrelated kidney donors in the United States. Am J Transplant 2007;7:1047-1054, with permission. |

|