Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are defined as the presence of more than 100,000 bacterial colony-forming units per milliliter (cfu/mL) of urine. Associated signs and symptoms include frequency, dysuria, urgency, cloudy urine, lower back pain, fevers, hematuria and pyuria (urine white cell count greater than 10,000/mL). Encompassing a triad of cystitis, urethral syndrome and pyelonephritis, UTIs are one of the most common medical conditions requiring outpatient treatment, with complications resulting in significant morbidity, mortality and financial cost, the latter estimated at $1.6 billion/annum to the US economy alone [1].

Those particularly at risk include infants, pregnant women, the elderly (particularly those in extended care facilities), and patients who are immunosuppressed, have spinal cord injuries, indwelling urinary catheters, diabetes, multiple sclerosis or other underlying neurological or urological anatomical abnormalities. The aim of this chapter is to identify, report and evaluate the evidence to answer common clinical dilemmas in prophylaxis and treatment of urinary tract infections in adults.

Probiotics/antiseptics

Cranberries have been used widely for the prevention and treatment of UTIs for several decades. Ninety percent water, cranberries also contain mallic acid, citric acid, quinic acid, fructose and glucose. Although controversial, it is proposed that fructose and proacanthocyanidins inhibit adherence of type 1 and a-galactose-specific fimbriated Escherichia coli to the uroepithelial cell lining of the bladder. Urinary acidification with vitamin C is also proposed, but a lack of evidence for its ability to significantly alter urinary pH as well as concerns regarding the risk of calcium oxalate stone formation have limited its widespread use.

Pharmaceutical

Prescription of antibiotics for preventing and treating UTIs is the most commonly used strategy. Additionally, manipulation of co-medications prescribed for co-morbidity may be beneficial, as sedatives, narcotic analgesics and anticholinergic drugs may contribute to urinary retention and so exacerbate symptoms and interfere with treatment of UTIs. Use of alpha-adrenergic blocking agents in appropriately screened men over 50 years old may also prove advantageous in reducing urinary retention caused by prostatism.

Methods of systematic literature review

Five common clinical dilemmas were identified and framed into clinical questions. To identify best evidence to answer each question, we sought related systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCT) and any additional RCTs in the published literature. The Cochrane Library and Medline were searched for relevant publications, limited to English-language articles. Sensitive search strategies were devised to answer each question, by combining medical subject headings (MeSH) with text words for UTI, including “urinary tract infection,” “bacteriuria” and “pyuria.” Terms specific to each question were then added (detailed with each question below). Each search strategy was then limited using terms to identify systematic reviews, meta-analyses and RCT. Search results were then screened, and all systematic reviews of RCTs that addressed each question were included, along with any RCTs published subsequently that also addressed the question. In addition, reference lists of all literature identified for inclusion were also screened to locate any potentially additional relevant publications, to detect either those excluded from the identified systematic reviews but still relevant to our questions or those not found by the database searches.

Once literature was identified, data for outcomes relevant to each question were abstracted and summarized, including details of methodological quality and quantative outcome data. To generate a recommendation from the evidence we had assembled, details of the evidence and its relation to each question were summarized using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE) system (www.gradeworkinggroup.org/) noting the quality, consistency, directness and other issues of the evidence [2].

Clinical question 9.1

For people with a history of UTI, does the ingestion of cranberries or cranberry products reduce the frequency of subsequent UTI?

Literature search

Search terms included: “beverages,” “fruit,” “cranberries,” “Vaccinium macrocarpon,” “Vaccinium oxycoccus,” “Vaccinium vitis-idaea.”

Evidence

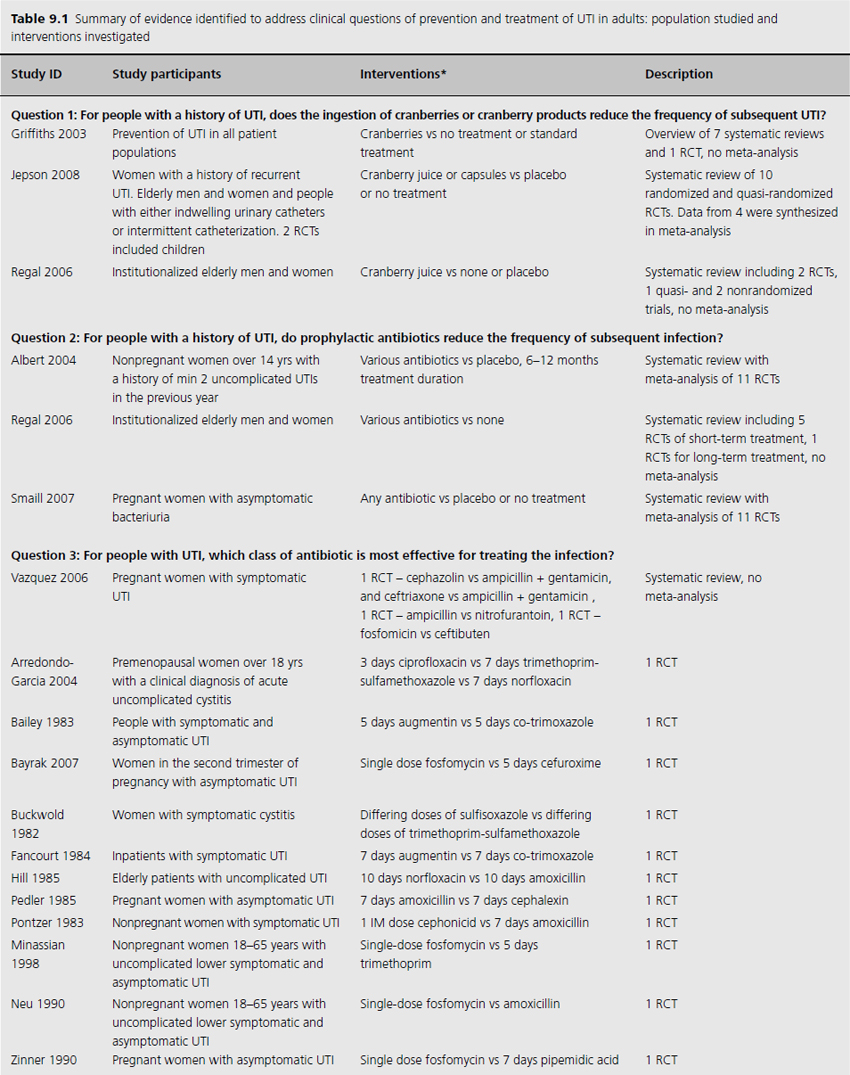

We included three systematic reviews of RCTs and quasi-RCTs [3–5]. One review also included nonrandomized trials (Table 9.1) [5]. No additional RCTs were identified that were not already included in the reviews. Two of the reviews had broad inclusion criteria [3,4] while the third was restricted to trials involving institutionalized elderly people [5]. Most of the RCTs included in the three reviews evaluated the effectiveness of either cranberry juice/cocktail or capsules versus placebo.

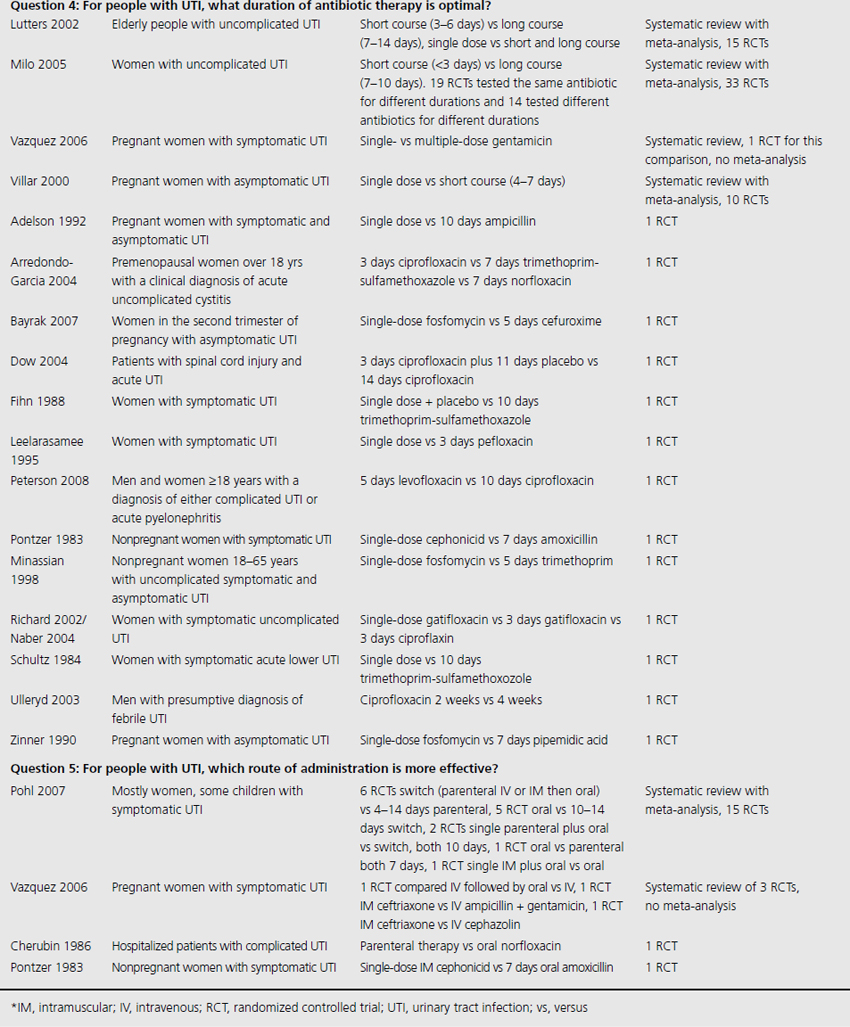

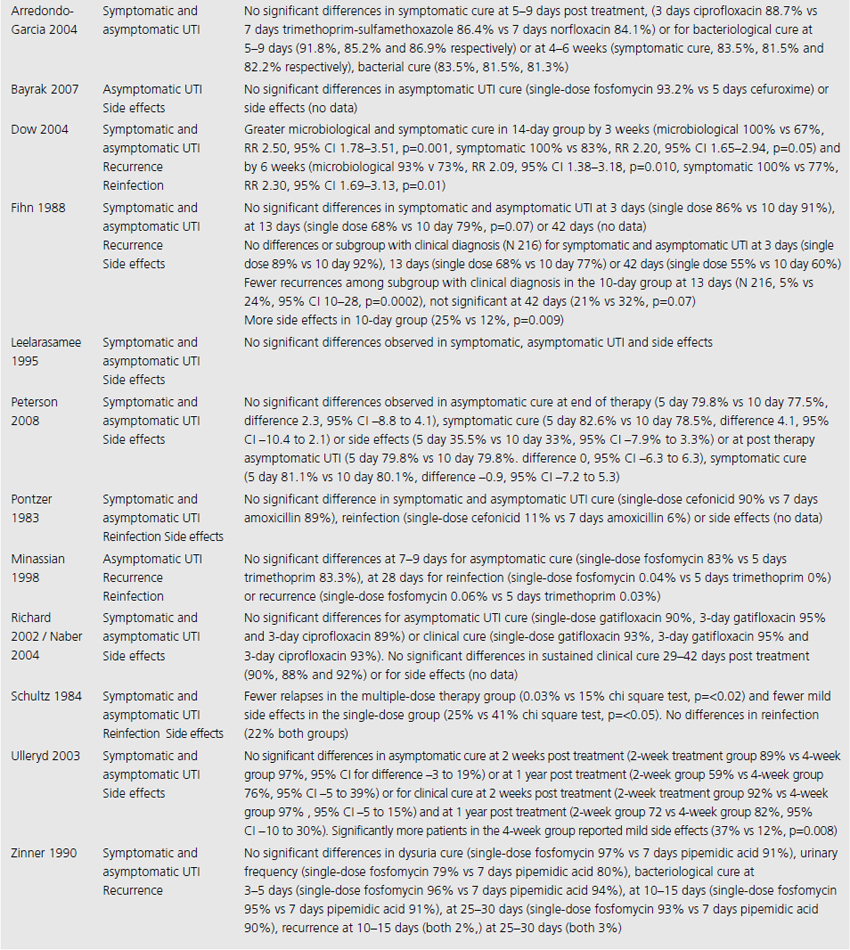

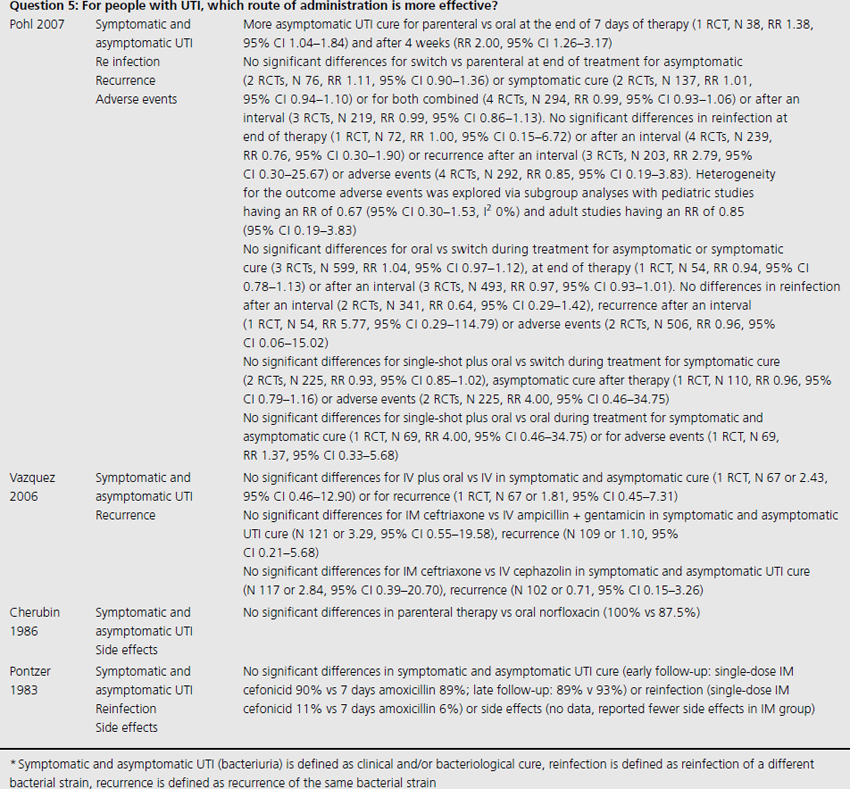

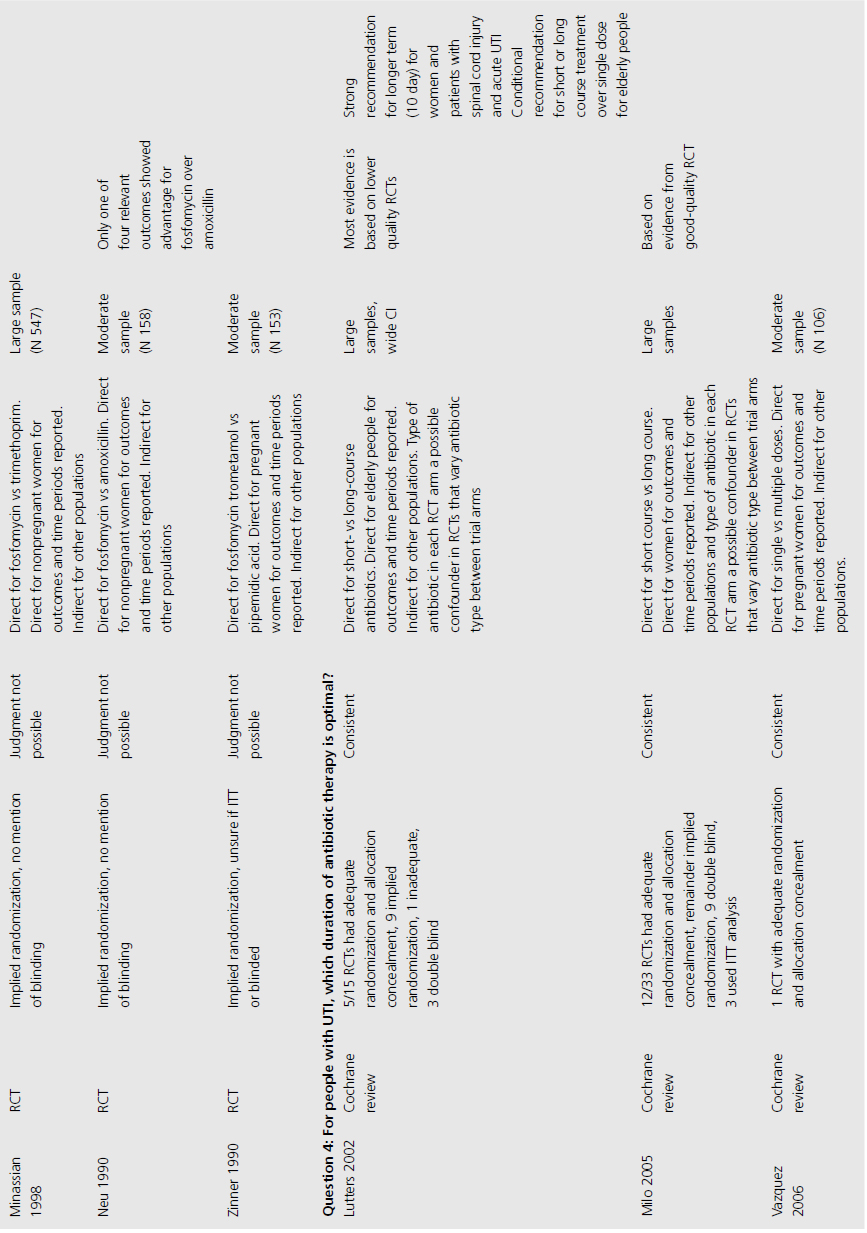

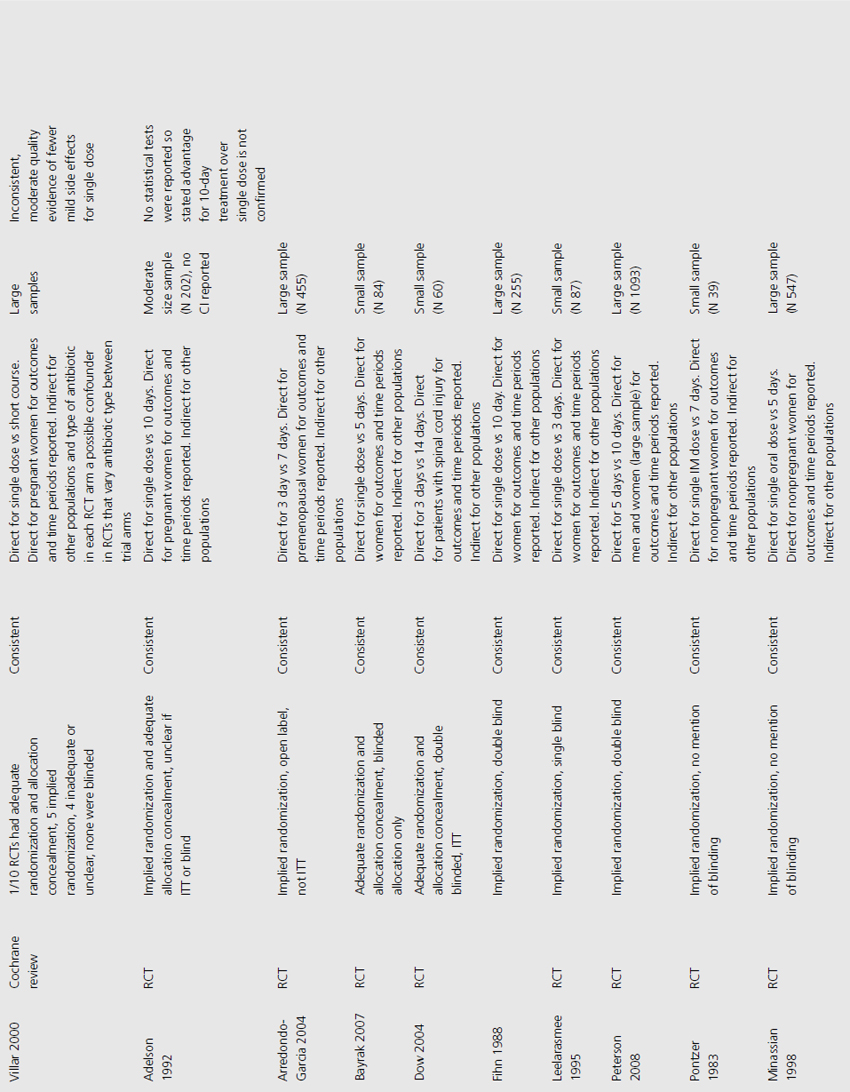

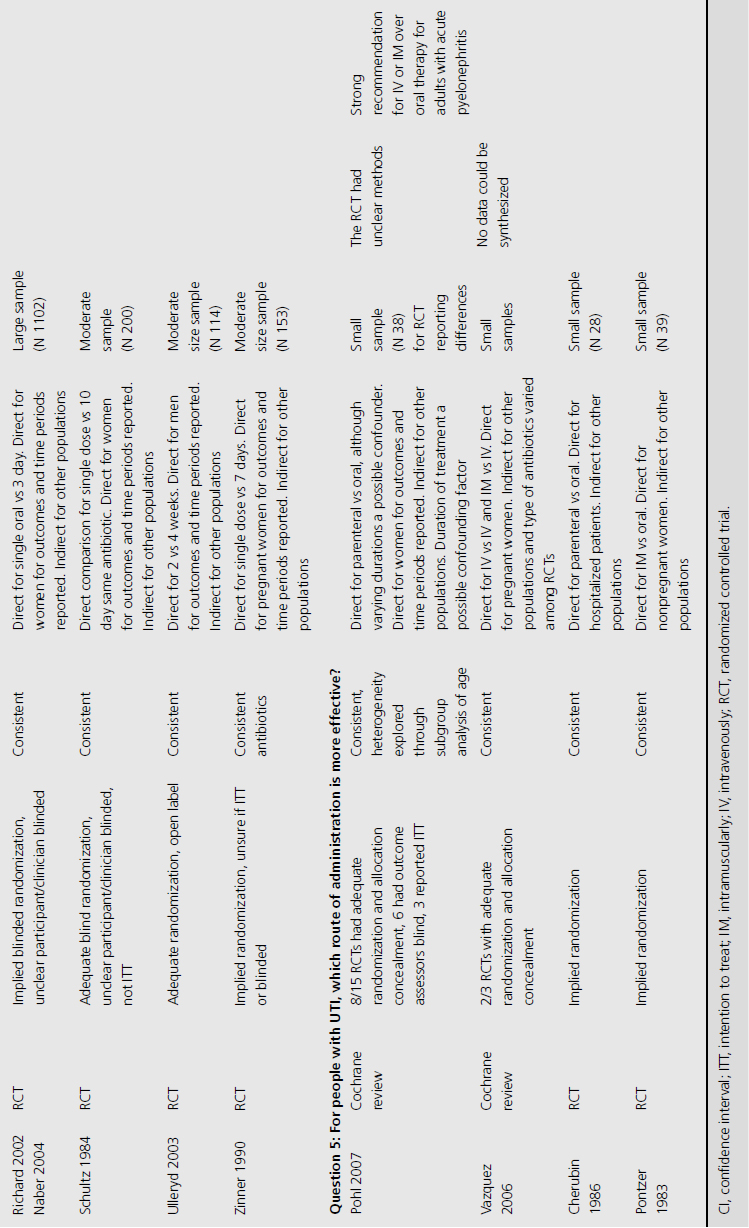

Table 9.1 Summary of evidence identified to address clinical questions of prevention and treatment of UTI in adults: population studied and interventions investigated

Results

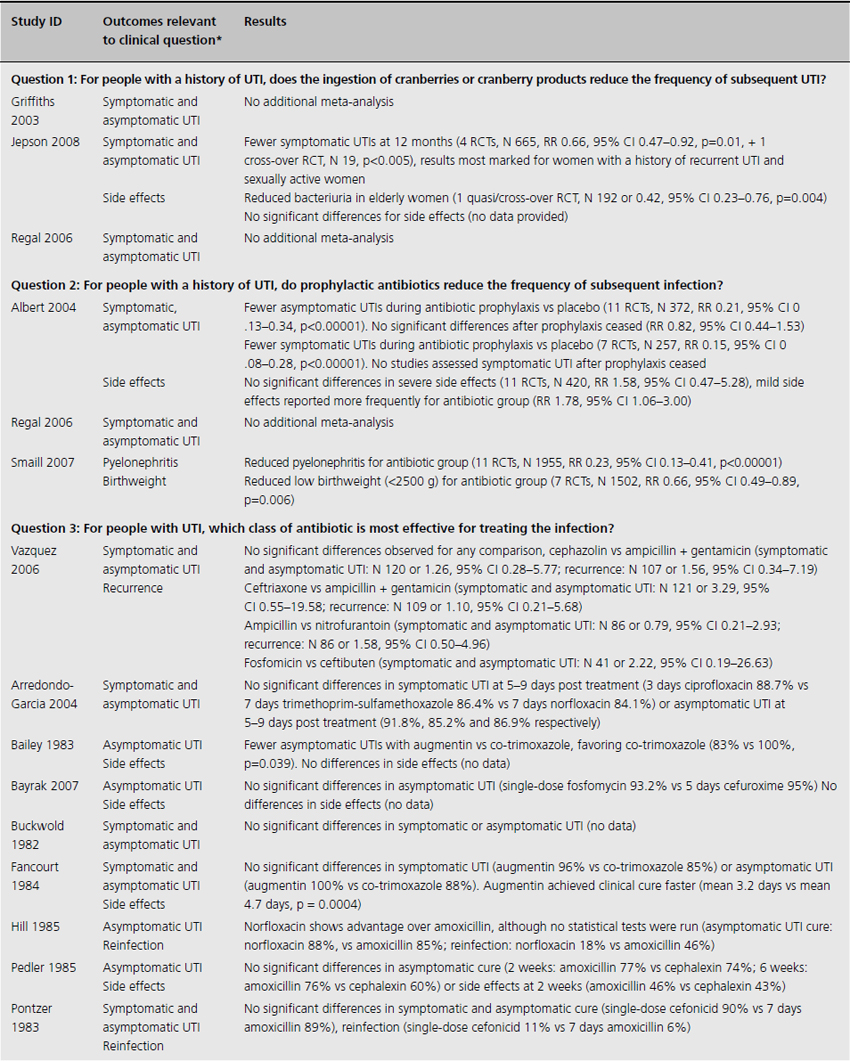

One systematic review included meta-analysis of four RCTs evaluating 665 patients, concluding that cranberry products significantly reduced the incidence of UTI by 34% at 12 months compared with no treatment or placebo (relative risk (RR) 0.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.47–0.92), particularly amongst women with recurrent UTI (Table 9.2) [4]. The primary outcome of UTI was variably defined and included symptomatic UTI, symptoms plus single organism growth > 104 cfu/mL or > 100,000 cfu/mL or detection of asymptomatic or symptomatic bacteriuria > 106 cfu/mL on monthly urine culture. The reduction in experiencing at least one symptomatic UTI was more marked amongst participants with a history of recurrent UTI and for women with uncomplicated UTI, with a 39% reduction (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.40–0.91). For elderly men and women, and participants with urinary catheters (intermittent or indwelling), there was no significant difference in incidence of symptomatic UTI. Six additional RCTs were identified in the review but not included in the meta-analysis because of methodological issues or lack of available data to contribute to the data synthesis. Of these, one cross-over RCT reported significant reduction in symptomatic UTI episodes amongst the group of sexually active 18–45-year-old nonpregnant women treated with cranberry product (six UTI cranberry group versus 15 UTI placebo group, N 19, p < 0.05), whilst a quasi-RCT reported a 58% reduction in rate of asymptomatic UTI amongst cranberry-treated elderly women (N 971 urine samples or 0.42, CI 0.23–0.76, p = 0.004). The remaining two systematic reviews identified no further contributory trials or data [3,5].

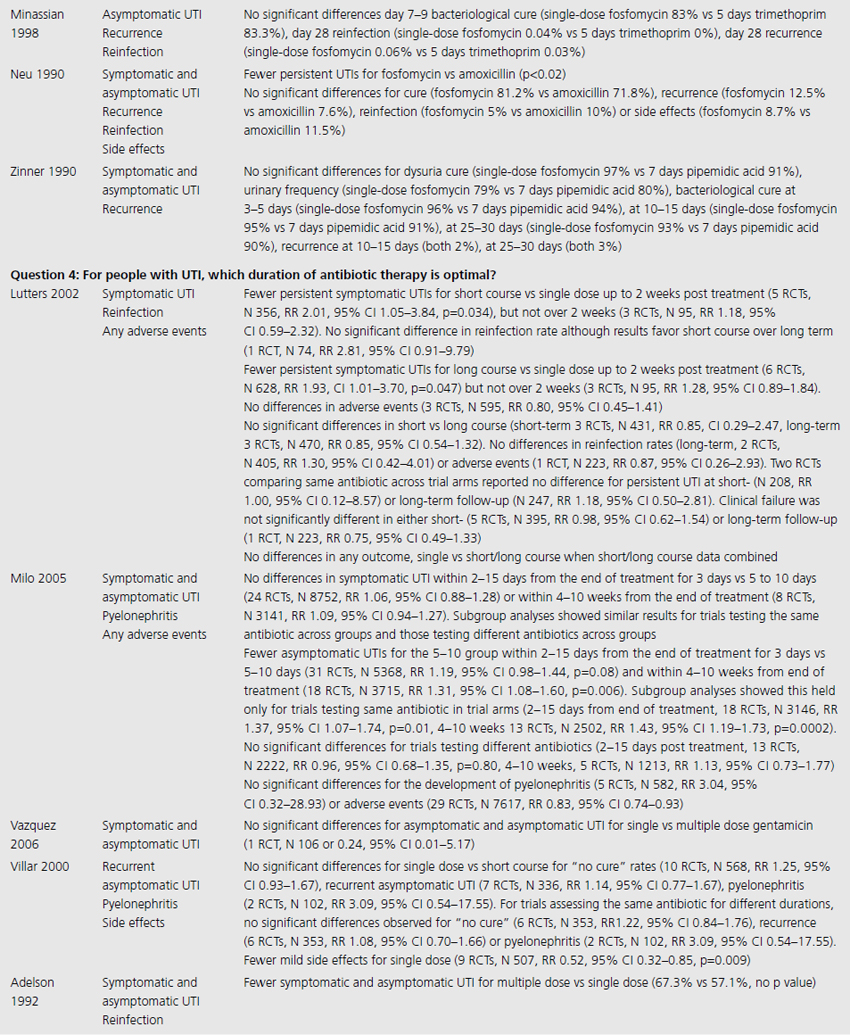

Table 9.2 Summary of evidence of effects of interventions for prevention and treatment of UTI in adults

Grade profile

Quality

The 10 RCTs evaluated in the Jepson systematic review were of variable quality: of the four combined for meta-analysis, three were double blinded, three had adequate allocation concealment, and two reported results by intention to treat (ITT; Table 9.3) [4]. Only two RCTS that were not included in the meta-analysis reported significant results. One of these used unclear methods of allocation, was cross-over in design and did not analyze results by ITT, whilst the other used quasi-randomization, was double blinded but did not use ITT analysis.

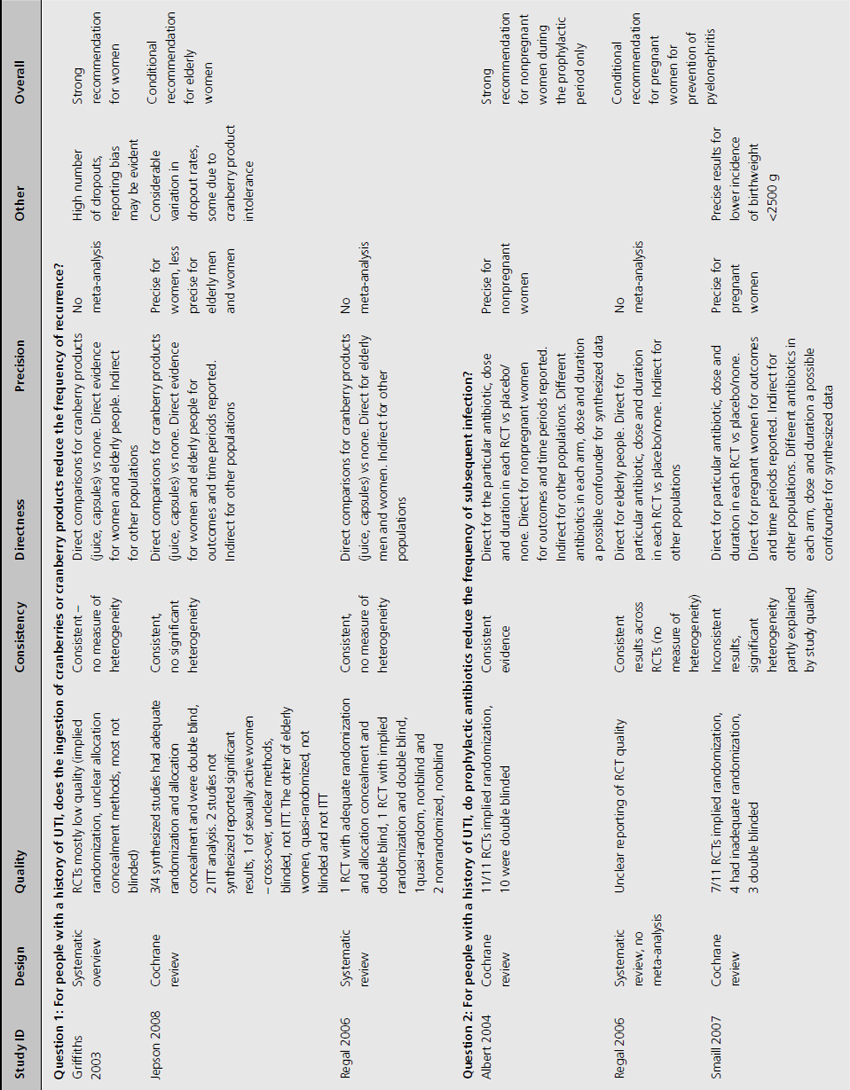

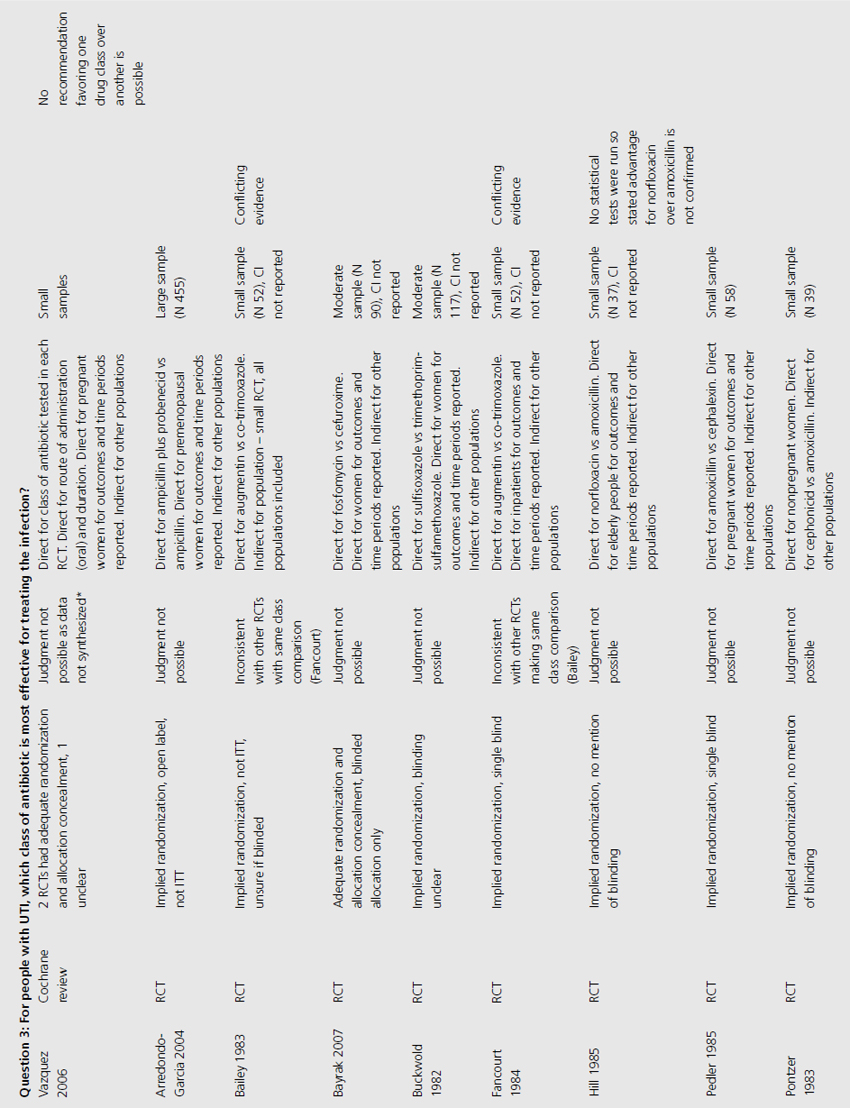

Table 9.3 Grade profile of identified evidence for clinical questions

Consistency

Trials varied in duration (from 4 weeks to 1 year of active treatment), population (from sexually active women to patients 1 year post spinal cord injury), and dosage (30–300 mL/day cranberry juice or cranberry capsules containing unquantified concentration of active cranberry product). Despite these differences, estimates of treatment effect were similar amongst synthesized trials, with no significant heterogeneity observed among population subgroups.

Precision

Estimates of effect were statistically significant for women with uncomplicated recurrent UTI and elderly women (narrower CI: 0.40–0.91 and 0.23–0.76 respectively), but less certain for elderly men and women combined (CI 0.21–1.22) and for patients with neuropathic bladders (CI 0.51–2.21), with small population size in this latter group (N 48).

Directness

All trials examined direct, unconfounded comparisons of cranberry product versus placebo or no treatment. Direct evidence for all sub-populations of interest was included.

Other considerations

Dropout rates differed markedly among trials, and reasons for this were not clear.

Recommendations

For women with recurrent UTI, we propose a strong recommendation (Grade 1A) that daily intake of cranberry juice or capsules can reduce the incidence of symptomatic UTI compared to no cranberry product (see Table 9.3) based on consistent, direct, high-quality and precise evidence.

A conditional recommendation (Grade 2B) supports the role of cranberry product in reducing the incidence of asymptomatic bacteriuria in elderly women. This is based on less precise evidence from one RCT and evidence from one quasi-RCT

The unresolved issue in applying these results in clinical practice is that the minimally effective dose of cranberry product remains unclear.

Clinical question 9.2

For people with a history of UTI, do prophylactic antibiotics reduce the frequency of subsequent infection?

Literature search

The following search terms were used: “antibiotic prophylaxis,” “antibiotics,” “urinary anti-infective agents.”

Evidence

Three systematic reviews assessed prophylactic antibiotics versus placebo or no treatment for preventing UTI (see Table 9.1) [5–7]. Again, no additional RCTs were identified. Active prophylaxis agents investigated included a range of antibiotic classes, and members of those classes, with a variety of dosages, dosing schedules and durations of treatment. The outcome reported in reviews and contributing RCTs varied, and defined UTI as either microbiological UTI (culture of more than 100,000 cfu/mL) or clinical recurrence. The three reviews examined prophylactic antibiotic use in three different patient populations; one review included 10 RCTs of antibiotics versus placebo, in nonpregnant women with a history of at least two uncomplicated UTIs in the previous year [6]. Another included only pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria, which affects 5–10% of pregnancies and can lead to acute pyelonephritis in up to 30% of mothers if left untreated [7]. The third review included only institutionalized elderly people [5].

Results

For nonpregnant women with a history of two or more uncomplicated UTIs within the previous year, results were synthesised from 11 trials comparing any antibiotic prophylaxis regimen of at least 6 months’ duration versus placebo (see Table 9.2) [6]. During the active treatment phase, antibiotics significantly reduced the risk of microbiological recurrence by 79% (N 372, RR 0.21, CI 0.13–0.34), and clinical recurrence by 85% (N 257, RR 0.15, CI 0.08–0.28). Microbiological recurrence was defined as recurrence of a positive urine culture of > 106 cfu/mL with isolation of a responsible agent not necessarily the same as that causing original infection or pyuria (> 10,000 cfu/mL) plus symptoms. No significant advantage was seen amongst the antibiotic-treated group once prophylactic treatment had ceased. Antibiotic-treated subjects were 58% (N 420, RR 1.58, CI 0.47–5.28) more likely to describe severe side effects (defined as those requiring withdrawal of treatment) and 78% (RR 1.78, CI 1.06–3.00) more likely to describe mild side effects (defined as not requiring withdrawal of treatment) than those on placebo.

For pregnant women, comparing antibiotic prophylaxis versus placebo, synthesis of 11 RCTs (1955 women) showed a 77% reduction in incidence of pyelonephritis with antibiotics (RR 0.23, CI 0.13–0.41, p < 0.00001) [7]. Among contributing trials, the duration of prophylaxis varied from a single dose to continuation of antibiotics to 6 weeks post partum.

The third systematic review examined the use of prophylactic antibiotics in elderly patients resident in extended care facilities, but did not include a meta-analysis [5]. This review identified five RCTs examining the role of prophylactic antibiotics in patients with indwelling urinary catheters, and concluded that there was a potential role for antibiotics in reducing rates of UTI amongst those with short-duration urinary catheters (3–14 days), on the basis of reduced rates of bacteriuria in three trials. One RCT included patients requiring perioperative indwelling urinary catheters and described a reduction in incidence of bacteriuria from 63% in placebo-treated to 15% in the antibiotic prophylaxis group of patients post gynecological surgery (N 105). Another RCT included in the review saw 8% of treated patients develop UTI versus 26% in the placebo group of 200 patients undergoing a range of abdominal, orthopedic and gynecological interventions, whilst another RCT found statistically significant benefit in patients undergoing abdominal surgery (N 429, 23% incidence UTI in placebo versus 9% incidence in antibiotic group), but not amongst those having vaginal surgery (N 86, UTI 23% treated versus 21% control).

Grade profile

Quality

The review of nonpregnant women included 11 trials with implied randomization although method of allocation concealment was not adequately reported in any, and so was judged unclear by review authors, but 10 of the 11 were double blinded (see Table 9.3) [6]. For pregnant women, the review identified 11 RCTs that reported development of pyelonephritis, which was the only preventive outcome [7]. Of these, none clearly reported method of allocation concealment, four were quasi-randomized, three were described as double blind and an additional five employed placebo. The review of preventive management strategies for UTI in extended care facilities did not systematically report the methodological quality of the five RCTs of catheterized patients [5].

Consistency

Among RCTs of nonpregnant women, there was no heterogeneity of results demonstrated (I2 0%) [6]. For pregnant women, magnitude of treatment effect was inconsistent among trials (I2 64% for pyelonephritis), though direction of effect was consistent [7]. This may be explained by study quality. The systematic review of elderly patients enrolled a cohort of catheterized patients, varying from incontinent stroke patients to surgical candidates requiring short-term perioperative catheterization [5]. Results across trials were consistent, though no measure of heterogeneity was reported.

Precision

For nonpregnant women, precise data derive from large sample sizes and narrow confidence ranges of 0.13–0.34 (microbiological recurrence) and 0.008–0.28 (clinical recurrence) for risk reduction during active prophylaxis. For pregnant women, estimates of effect were also precise, with reduction in incidence of pyelonephritis (CI 0.13–0.41). The review of elderly patients provided no meta-analysis, with sparse data and no reporting of confidence intervals for individual RCTs, making assessment of precision impossible.

Directness

In all three systematic reviews, trials made direct comparison of antibiotic therapy versus placebo. Different antibiotics of varying doses and routes of administration were used, with active prophylactic periods varying between single dose and 12 months. The evidence is direct for each population tested, pregnant and nonpregnant women and elderly people and indirect for other populations.

Other

A significant reduction in the incidence of low birthweight babies was seen amongst antibiotic-treated pregnant women (RR 0.66, CI 0.49–0.89, I2 28%, p = 0.006).

Recommendation

For nonpregnant women, we propose a strong recommendation (Grade 1A) that prophylactic antibiotics reduce the risk of symptomatic and asymptomatic UTI, with only mild side effects observed (nausea, diarrhea and candidiasis) in those taking prophylactic antibiotics. This treatment advantage can be expected only during the period when antibiotics are being administered.

Amongst pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria we suggest a conditional recommendation (Grade 2B) based on moderate-quality evidence supporting antibiotic prophylaxis in reducing the frequency of pyelonephritis. This recommendation is less strong because evidence is from moderate-quality RCT, with some inconsistency of findings.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree