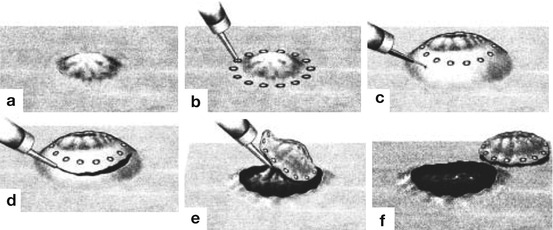

Fig. 3.1

Basic resection techniques of mucosal neoplasias by electrosnaring (a) or expanded snaring techniques (b, c, d, endoscopic mucosal resection EMR). Larger lesions (>20 mm) are only resectable in piecemeal fashion (e)

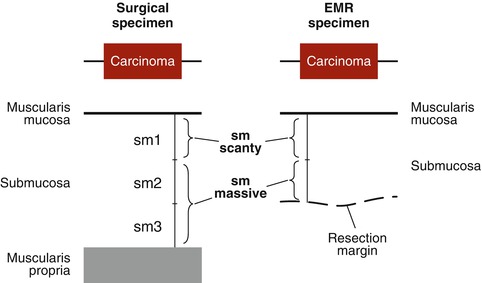

Fig. 3.2

Basic technique of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for en bloc resection of mucosal neoplasias (Adapted from Refs. [1, 2, 5, 8, 9], permission granted by John Wiley & Sons Inc.). (a) Small flat neoplasm without ulceration, (b) circumferential marking dots using coagulation current, (c) lifting of the lesion by submucosal injection, (d) circumferential mucosal incision around the marking dots, (e) visualize the submucosal space under the lesion using a transparent cap and dissect submucosal tissue until removal of the lesion. (f) The resection bed is examined for perforating vessels or injury to the proper muscle layer

En bloc resection with ESD is superior to piecemeal EMR for two reasons:

First, en bloc resection is fundamental for precise histopathological evaluation, to determine tumour grading [G1-G3], and category [pT1a (m1-3), pT1b(sm1-3)], lymphatic invasion [Ly 0 or Ly 1], venous invasion [V 0, V 1] and the resection status [R0, R1, (R2)] [2, 5, 9, 11, 12]. Endoscopic resection of mucosal neoplasias is permissible when at least R1-resection is achieved (diagnostic en bloc resection) and further management (surgery or adjuvant treatment) will be defined in an interdisciplinary tumour board. R1-resection of early gastric cancer followed by surgical gastrectomy and lymphadenectomy did not worsen prognosis [13]. However, frank R2-resections must be avoided, as that impairs the tumour-related prognosis of the patient. Endoscopic signs for deep submucosal invasion of an early cancer warrant surgical full-wall resection combined with lymphadenectomy (curative surgical approach) [1, 6]. Progress in magnifying image-enhanced endoscopy (IEE) does now allow accurate endoscopic cT-staging of mucosal tumours.

Second, complete en bloc resection with R-0-status for low-risk malignancy or premalignant neoplasms avoids local recurrence of the neoplasm with high degree of certainty. The recurrence rate for early mucosal cancers (sm < 1, L0, V0; G1 or G2) complying with histological criteria for curative resection (see below) is less than 3.5 % for ESD, whereas with piecemeal EMR (always R1-resection), it is in the range of 5–20 % for intramucosal gastric cancer [11, 14–16], 10–26 % for oesophageal squamous cell cancer [17–20] and 14–35 % for colonic neoplastic lesions [21]. Higher rates of curative resection have established ESD as standard of care superior to piecemeal EMR [1, 11].

Note:

Development of ESD led to major clinical benefits:

Enhanced endoscopic detection/analysis of early-stage neoplasias

Organ-sparing curative tumour resection, especially in the elderly

Precise histopathological staging of pT category/resection status

En bloc resection (curative) with very low risk of recurrence

3.3 Criteria of Lesions for Endoscopic En Bloc Resection

Endoscopic diagnosis of neoplasias focuses on the assessment of malignancy, lateral extension and depth of invasion of early neoplastic lesions. In subpedunculated/pedunculated adenomas inconspicuous of tumour invasion of the stalk, R0-resection may easily be achieved by simple electro-snaring and in flat neoplasias (0-IIa and 0-IIb) of limited size (d ≤ 20 mm) by EMR techniques (Fig. 3.1). Flat lesions of size larger than 20 mm or depressed lesions (0-IIc) larger than 10 mm are not likely to be removable en bloc using EMR techniques and should therefore undergo ESD (Fig. 3.2), when not appearing deeply submucosa-invasive on enhanced imaging (Chaps. 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11) and high-resolution endoscopic ultrasound (20 MHz, when available; see Chap. 5).

Note:

General indication for ESD is any mucosal neoplasia (premalignant/malignant)

Suitable only for piecemeal EMR (by electro-snaring), but

Demanding en bloc resection (for pT staging and cure), without

contraindication:

Evidence of deep invasion of submucosa (sm2-3)

In general, lesions should be biopsy-proven in most cases prior to ESD. However, typical flat depressed neoplasias type 0-IIc with premalignant/malignant surface pattern should be resected en bloc rather than biopsied. We recommend to take only few (1 or 2) targeted biopsies from the most suspicious part of flat lesions, as subsequent submucosal scarring is interfering with submucosal dissection. However, the mucosa surrounding lesions type 0-IIb and 0-IIc should be confirmed as non-neoplastic by biopsies just outside the planned margin of resection in chronic gastritis and Barrett’s oesophagus. The final test for extent of sm invasion – when starting to conduct ESD – is the fashion of lifting off the lesion upon proper submucosal injection [22]. Nevertheless, some neoplasias exhibit partial poor lifting due to severe submucosal fibrosis without deep submucosal invasion (no sm signs in surface/capillary pattern).

For endoscopic resection, neoplasias must not show signs of deep sm invasion (sm2-3), whereas superficial invasion of well-differentiated mucosal cancer within the upper third of sm layer (sm1) is acceptable [23] (Fig. 3.3). The recommended level of dissection in most situations is the deep sm2 layer close to sm3 layer to avoid damaging the lesion as well as injuring the fascia of the proper muscle. Furthermore, the sm1 and sm2 layers contain a network of branching vessels, and the sm3 layer is nearly devoid of small vessels except voluminous perforans vascular pedicles. The relatively avascular stratum at/above sm3 is most suitable for submucosal dissection [24].

3.4 Indications for Endoscopic En Bloc Resection in the GI Tract

The indications for ESD as established in Japan are based on pathohistological staging of a large series of resected tumours – and define lesions with minimal risk of metastatic spread to regional lymph nodes [26–33]. After curative ESD (R0) for mucosal neoplasm fulfilling guideline ESD criteria, the probability of lymph node metastasis is very low (<3 %) and the rate of local recurrence is close to zero. Established indications for en bloc ESD are listed in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1

Indications for endoscopic en bloc resection of GI neoplasias

Organ | Indications for | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

(A) Stomach | ESD – classical indications | |

Mucosal adenocarcinoma, intestinal type G1 or G2, size d ≤ 2 cm, no ulcer | ||

ESD – expanded indications | ||

Adenocarcinoma, intestinal type, G1 or G2, any size without ulcer | ||

Adenocarcinoma, intestinal type, G1 or G2, sm-invasive <500 μm | ||

Adenocarcinoma, intestinal type, G1 or G2, d ≤ 3 cm, with ulcer | ||

Adenocarcinoma diffuse type, G3 or G4, size d ≤ 2 cm, no ulcer | ||

(B) Oesophagus | ESD – classical indications | |

SCC type 0-IIb (HGIN or G1, G2), intramucosal (m1, m2), any size | ||

Barrett adenoca. type 0-II (G1, G2), intramucosal (m1, LPM), no ulcer. | ||

ESD – expanded indications | ||

SCC type 0-II (HGIN, G1, G2) slightly invasive (m3, sm<200 μm), any sizea, clinical N 0. | ||

Barrett adenocarcinoma type 0-II (HGIN or G1, G2), mucosal (≤ MM), clinical N 0. | ||

(C) Colorectum | ESD indications (preliminary criteria)b | |

Any neoplasias >20 mm in diameter without signs of deep submucosal invasion, indicative for en bloc resection and unsuitable for EMR en bloc: | ||

LST-granular type (villous adenoma +/− HGIN)c | ||

LST-nongranular type | ||

Mucosal carcinoma (HGIN, G1 or G2) or superficially sm-invasived | ||

Depressed-type neoplasias (0-IIc) | ||

Neoplasias type 0-I or 0-II with pit pattern type VI (irregular) | ||

Sporadic localized neoplasias in chronic ulcerative colitis | ||

Colorectal carcinoids of diameter <20 mm [EMR, when diameter <10 mm] |

Note:

Guideline (classical) indications aim for curative endoscopic resection.

En bloc EMR or ESD of differentiated early cancers (grade G1 or G2) is curative when cancer does not invade the lymph or blood vessels (L0, V0) and vertical invasion beyond muscularis mucosae does not exceed 200 μm in squamous cell-lined oesophagus, 500 μm in the stomach (and probably in Barrett’s oesophagus) and 1,000 μm in the colorectum. Then, the probability of metastasis to regional lymph nodes is less than 3 % [1].

Surgery is indicated after ESD of early cancer for any of the following:

Vertical (deep) margin is tumour-positive (R1).

Deep submucosal invasion (sm2–sm3, exceeding organ-specific depth).

Lymphovascular/vascular tumour infiltration is positive (Ly 1 or V 1).

Tumour budding is seen at the deepest front of invasion.

Cancer grading is poorly differentiated or undifferentiated (G3, G4), except in the stomach for cancer G3 or G4 of size <2 cm without ulceration.

3.5 Outcome of ESD and Management of Complications

3.5.1 Outcome of ESD

ESD yields en bloc resection in 84–98 % of cases and is complicated by perforation in up to 10 % (and during untutored learning curve in up to 20 %). Gastric and oesophageal ESD had been standardized, but colorectal ESD has not been standardized until 2012 because of associated technical difficulties, such as winding thin wall, haustral folds, less stable position of the endoscope in flexures, peristalsis and respiratory movements. Current benchmark criteria for outcome of ESD in the locations of the GI tract are listed in Table 3.2. Organ perforation during ESD of differentiated mucosal gastric cancer did apparently not increase the risk of peritoneal dissemination [40].

Table 3.2

Organ-specific outcome of curative ESD for classical indications

Median [range] | Oesophagus (% of ESDs) | Stomach (% of ESDs) | Colorectum (% of ESDs) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

SCL-E | CCL-E | |||

En bloc resection | 100 [95–100] | 100 | 92 [83–98] | 89 [87–93] |

Curative resection | 90 [79–97] | 79 | 83 [74–93] | 80 [75–89] |

Local recurrencea | 0b; 0b | 0c | 1.5 [0–3.2] | 0.3 [0–0.5] |

Recurrence-free OS | 100b;100b | 90c | 98c[94b–100d] | 99.6 [98–100]c |

Perforation | 0 [0–5] | 0 | 4 [3–11] | 14 [10–20]e |

Bleeding | 0 [0–2] | 5 | 1.6 [0–23] | 1.4 [0.7–8.6] |

Surgical repair | 0 | 0 | 0 [0–3.5] | 0.3 [0–4.3] |

ESD mortality | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

3.5.2 Complications of ESD and Complication Management

The risk of perforation during ESD increases with low experience and poor skill of the operator and larger size, submucosal fibrosis and challenging location of the lesion. The risk is lowest in gastric corpus and rostral antrum and is increasing in different sites and organs in the following order: prepyloric antrum, fundic and subcardiac stomach and even more in thin-walled organs such as the rectum, oesophagus, descending and transverse colon, ascending colon, cecum, sigmoid colon, splenic and hepatic flexure and especially duodenum [41].

Further risk factors are respiratory movement of the organ or endoscope (in right colon), lesions straddling haustral folds, and marked submucosal fibrosis. Submucosal fibrosis is common beneath nongranular LST, larger protruding lesions (diameter >4 cm), recurrent lesions after EMR, beneath lesions in colonic flexures, next to chronic ulcers, or in chronic inflamed mucosa (Barrett’s oesophagus and ulcerative colitis) [7, 52, 54–56]. In the colon and duodenum, even cautious contact coagulation of small vessels overlying the thin (~1 mm) proper muscle layer may cause free mini-perforation. In the duodenum, mucosal ulcer after ESD carries a high risk of delayed re-bleeding or perforation, due to aggressive pancreatobiliary secretions, and should be closed by adaption and clipping of mucosal margins.

Most small perforations can be closed by clipping in experienced hands and treated with intravenous antibiotics, parenteral nutrition and clinical follow-up for a few days – without surgery [57]. There are some tricks and devices to close even larger perforations [54, 57, 58]. Frank pneumoperitoneum due to shortly delayed clipping of perforation can impair cardiorespiratory performance and must be relieved by peritoneal puncture using, e.g. a 20-gauge intravenous Teflon cannula [57].

Delayed perforation (after 2–5 days) is rare, occurring after 0.3–0.7 % of colonic ESDs, but carries a high risk of peritonitis, because abdominal pain is only slowly increasing. A high rate (40.2 %) of electrocoagulation syndrome (rebound tenderness and fever or marked leukocytosis) had occurred in addition to 8 % free organ perforation in an initial series of 95 consecutive colorectal ESDs [59] – presumably due to the excessive use of electrocoagulation during the learning curve. The size of delayed perforation may be larger, when much coagulation current had been used at the proper muscle during ESD. Repair is by open surgery [1, 57, 60, 61].

Risk of bleeding is increased at major curvature, antrum, and cardia in the stomach, duodenum and distal rectum. Late re-bleeding is best prevented by clipping of any coagulated perforating vessels in the resection bed after ESD.

Severe stenosis occurs after ESD involving more than 70 % of the circumference of the oesophagus, prepyloric antrum or anorectal channel. In the oesophagus, stenosis can be prevented by repeated cautious balloon dilatation [62, 63]. Biodegradable stents have also been used to correct oesophageal stenosis after ESD [64]. Repeated digital or balloon dilatation avoids stricturing of the anorectal channel, combined with daily application of a corticoid suppository for about 1 month. Complete circumferential ESD is contraindicated in prepyloric antrum and pylorus, because severe gastric outlet stenosis is unavoidable, and balloon dilatation carries a high risk of perforation [65]. Gastric mucosa must remain intact on at least 30% of the circumference in the prepyloric antrum.

Note

ESD in high-risk locations requires high skills and at least the level of competence for ESD (see below). Operators must be cautious and slowly raise their level of challenge, preferably under tutoring by proven ESD experts.

3.6 ESD: Minor Invasive Endoscopic Surgery

ESD is a minor invasive endoscopic surgery and considered a relatively low-tech, but highly skilled, procedure demanding rigorous learning even from skilled interventional endoscopists.

The principal skills that need to be acquired are:

Endoscopic competence for accurate assessment of early neoplasias

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree