Chapter 14 Primary biliary cirrhosis

1 Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a chronic cholestatic liver disease that usually affects middle-aged women.

3 The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and interleukin-12 signaling axis are particularly relevant biologically in the origin of this autoimmune small duct cholangitis.

4 Most patients are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis; symptom severity does not always correlate with disease severity.

5 The combination of persistently cholestatic liver chemistry studies, normal biliary imaging, and the presence of antimitochondrial antibody are usually sufficient to diagnose PBC. Liver biopsy is not recommended by consensus guidelines unless doubt exists over the diagnosis or antimitochondrial antibody is absent.

6 Treatment guidelines recommend that ursodeoxycholic acid, the only treatment for PBC approved by the Food and Drug Administration, be given to patients with PBC. The absence of a biochemical response to treatment is associated with a poorer outcome, but additional therapies for such patients are lacking. Randomized data failed to provide support for the use of methotrexate or colchicine, and fenofibrate use remains anecdotal. New agents (farnesoid X–receptor agonists) appear promising.

Epidemiology

1. Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a female-predominant (90% to 95%) disease seen in all ethnicities.

2. An estimated 1 in 1000 white women who are more than 40 years old have PBC. One robust UK estimate of annual incidence was 32.2 per million per year, with an estimated prevalence of 334.6 per million

3. The age of onset typically ranges from 30 to 70 years, and the diagnosis of PBC is increasingly made through routine screening. Diagnosis before menarche has not been reported.

Genetics

1. Genetic factors play a role in PBC, although the disorder is not the consequence of a single genetic mutation.

2. Approximately 1 in 20 patients has a family member affected with PBC. Patients and their family members are more likely to have other autoimmune diseases, particularly celiac disease and scleroderma.

3. Lack of complete concordance for PBC in identical twins adds to the evidence that environmental factors are also important; factors proposed include retroviral infection, xenobiotics, and molecular mimicry from infection. Smoking is an important risk factor for disease severity and progression.

4. An association with the class II human leukocyte antigen (HLA) locus is universally recognized but not understood mechanistically.

5. Genome-wide association testing and replication studies have identified the IL12A, IL12RB2, IRF5, and 17q21 loci as particularly relevant to PBC pathogenesis, thus implicating the Th1 and Th17 cell lineages, as well as demonstrating shared risk variants with other autoimmune diseases (e.g., celiac disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, asthma).

Immunologic Abnormalities

1. Antimitochondrial antibody (AMA)

c. Can be seen in other liver diseases, including acute liver failure, drug injury and autoimmune hepatitis

d. Not one antibody but a family of antibodies that react with different antigens within the mitochondria

Antimitochondrial antibody PDH-E2

Antimitochondrial antibody PDH-E2

Antimitochondrial antibody PDH-E2

Antimitochondrial antibody PDH-E2– Directed principally against the dihydrolipoamide acyltransferase component (E2) of the ketoacid dehydrogenase complexes on the inner mitochondrial membrane

e. Significance of AMA

Biochemical changes to the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex during biliary epithelial cell apoptosis appear important in explaining the relevance of AMA in PBC.

Biochemical changes to the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex during biliary epithelial cell apoptosis appear important in explaining the relevance of AMA in PBC.

Pyruvate dehydrogenase and the other mitochondrial antigens are aberrantly expressed on the luminal surface of biliary epithelial cells from patients with PBC but not from control subjects or patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Pyruvate dehydrogenase and the other mitochondrial antigens are aberrantly expressed on the luminal surface of biliary epithelial cells from patients with PBC but not from control subjects or patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Pyruvate dehydrogenase E2 is expressed in bile duct epithelial cells before T-lymphocyte cytotoxicity occurs.

Pyruvate dehydrogenase E2 is expressed in bile duct epithelial cells before T-lymphocyte cytotoxicity occurs.

No correlation exists between the presence or titer of AMA and the severity of the course of PBC; antibody titer can fall with treatment.

No correlation exists between the presence or titer of AMA and the severity of the course of PBC; antibody titer can fall with treatment.

High titers of AMA can be produced in experimental animals by immunization with pure human pyruvate dehydrogenase, but these animals do not develop liver disease; induction of autoimmune cholangitis following a chemical (2-octynoic acid) xenobiotic immunization has been reported.

High titers of AMA can be produced in experimental animals by immunization with pure human pyruvate dehydrogenase, but these animals do not develop liver disease; induction of autoimmune cholangitis following a chemical (2-octynoic acid) xenobiotic immunization has been reported.

Biochemical changes to the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex during biliary epithelial cell apoptosis appear important in explaining the relevance of AMA in PBC.

Biochemical changes to the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex during biliary epithelial cell apoptosis appear important in explaining the relevance of AMA in PBC. Pyruvate dehydrogenase and the other mitochondrial antigens are aberrantly expressed on the luminal surface of biliary epithelial cells from patients with PBC but not from control subjects or patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Pyruvate dehydrogenase and the other mitochondrial antigens are aberrantly expressed on the luminal surface of biliary epithelial cells from patients with PBC but not from control subjects or patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Pyruvate dehydrogenase E2 is expressed in bile duct epithelial cells before T-lymphocyte cytotoxicity occurs.

Pyruvate dehydrogenase E2 is expressed in bile duct epithelial cells before T-lymphocyte cytotoxicity occurs. No correlation exists between the presence or titer of AMA and the severity of the course of PBC; antibody titer can fall with treatment.

No correlation exists between the presence or titer of AMA and the severity of the course of PBC; antibody titer can fall with treatment. High titers of AMA can be produced in experimental animals by immunization with pure human pyruvate dehydrogenase, but these animals do not develop liver disease; induction of autoimmune cholangitis following a chemical (2-octynoic acid) xenobiotic immunization has been reported.

High titers of AMA can be produced in experimental animals by immunization with pure human pyruvate dehydrogenase, but these animals do not develop liver disease; induction of autoimmune cholangitis following a chemical (2-octynoic acid) xenobiotic immunization has been reported.Pathogenesis

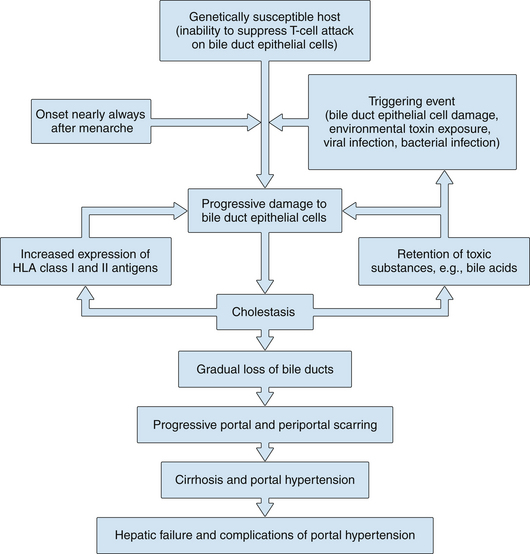

1. Chronic nonsuppurative granulomatous cholangitis is a better description of the disease than PBC, and at least two related processes appear to lead to hepatic damage (Fig. 14.1).

2. The first process is the chronic, often granulomatous, destruction of small bile ducts, presumably mediated by activated lymphocytes. It seems likely that the initial destructive bile duct lesion in PBC is caused by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. A component of autoimmune hepatitis cannot be excluded, and clinically a few patients (variably reported at 5% to 10%) have some evidence of this.

Bile duct cells in patients with PBC express increased amounts of class I HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C and class II HLA-DR antigens, in contrast to normal bile duct cells.

Bile duct cells in patients with PBC express increased amounts of class I HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C and class II HLA-DR antigens, in contrast to normal bile duct cells.

Bile duct cells in patients with PBC express increased amounts of class I HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C and class II HLA-DR antigens, in contrast to normal bile duct cells.

Bile duct cells in patients with PBC express increased amounts of class I HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C and class II HLA-DR antigens, in contrast to normal bile duct cells.3. The second process includes chemical damage to hepatocytes in areas of liver where bile drainage is impeded by the destruction of the small bile ducts.

Retention of bile acids, bilirubin, copper, and other substances that are normally secreted or excreted into bile occurs.

Retention of bile acids, bilirubin, copper, and other substances that are normally secreted or excreted into bile occurs.

The increased concentration of some of these substances, such as bile acids, may further damage liver cells.

The increased concentration of some of these substances, such as bile acids, may further damage liver cells.

Retention of bile acids, bilirubin, copper, and other substances that are normally secreted or excreted into bile occurs.

Retention of bile acids, bilirubin, copper, and other substances that are normally secreted or excreted into bile occurs. The increased concentration of some of these substances, such as bile acids, may further damage liver cells.

The increased concentration of some of these substances, such as bile acids, may further damage liver cells.Pathology

Gross Findings

2. With progression of the disease, the liver enlarges further, becoming nodular and grossly cirrhotic with bile staining.

4. An increased prevalence of nodular regenerative hyperplasia is observed in the early stage of PBC; although varices and portal hypertension are most commonly associated with cirrhosis, presinusoidal portal hypertension can be seen as a result of this nodular regenerative hyperplasia in a few patients with PBC who do not have cirrhosis.

Hepatic Histology

2. Histologic staging is less relevant than biochemical response to treatment and liver function in clinical treatment, however, and is therefore not routinely evaluated in clinical practice. Additionally, noninvasive markers of fibrosis, particular transient elastography, have potential utility.

3. Considerations in interpreting liver biopsy staging:

b. Several stages may be seen on one biopsy specimen; by convention, staging is based on the most advanced lesion seen on the biopsy specimen.

c. Given that PBC is increasingly diagnosed at an earlier stage, it is less likely that characteristic pathologic observations can be made on needle biopsy specimens.

d. Histologic stages are as follows:

Stage I

Stage I

Stage I

Stage I– Injured bile ducts are usually surrounded by a dense infiltrate of mononuclear cells, most of which are lymphocytes (Fig. 14.2).

– These florid, asymmetrical destructive lesions of interlobular bile ducts are irregularly scattered throughout the portal triads and are often seen only on large surgical biopsy specimens of the liver in which adequate representation of small bile ducts occurs.