(1)

Gastroenterology and hepatology, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China, People’s Republic

Abstract

Endoscopic tunnel technique divides deliberately the wall of digestive tract into two-layer with the establishment of submucosal tunnel to ensure a safe barrier to prevent concerned serious complications in treatment of lesions from mucosa or muscularis propria. Even so, some complications might emerge inevitably. The most common complications are pneumatosis-related complications, including subcutaneous emphysema, mediastinal emphysema, pneumoperitoneum, and even pneumothorax. Mucosal perforation also happen occasionally, the incidence of which is 3.6–20 %. Hemorrhage, intraoperative or delayed, cannot be ignored in spite of its relatively low incidence. Gastroesophageal reflux is one of the most concerned complications of POEM, which influences the quality of life of the patients. Infection is one of most serious complications after operation, such as mediastinitis, peritonitis, pulmonary infection. Esophageal stricture is a major problem for patients with large esophageal mucosal lesions treated with tunnel technique, the incidence of which is closely related to length and circumferential area of lesions.

Endoscopic tunnel technique divides deliberately the wall of digestive tract into two-layer with the establishment of submucosal tunnel to ensure a safe barrier to prevent concerned serious complications in treatment of lesions from mucosa or muscularis propria. Even so, some complications might emerge inevitably.

The most common complications are pneumatosis-related complications, including subcutaneous emphysema, mediastinal emphysema, pneumoperitoneum, and even pneumothorax. Face, neck, and anterior chest wall are easier to develop subcutaneous emphysema. The incidence of pneumatosis-related complications of STER (submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection) is 6.25–50 %, among which pneumothorax accounts for 0–17 % [1–4]. The incidence of pneumatosis-related complications of POEM was 27.7–100 %, and pneumothorax accounts for up to 25.2 % [5–9]. Lack of serosa outside esophagus makes air free to flow and gather. Meantime, the boundary of esophageal circular and longitudinal layer is not clear, and the thin longitudinal muscle may be involved during circular myotomy of POEM. For en bloc resection of the tumor, full-thickness resection has to be adopted during STER, inclusive of gastric serosa. Those may be main reasons for occurrence of pneumatosis-related complications. Yet different incidences in different centers may be related to operational proficiency, CO2 gas insufflation, operation mode selection (transverse or longitudinal entry incision, complete or incomplete myotomy), and prior treatment history of patients. CO2 gas insufflation instead of air is extremely necessary to reduce the risk of pneumatosis-related complications for its rapid diffusion and absorption. The entry incision on anterior wall of the esophagus is also beneficial because the tunnel lead to the lesser curvature side at the cardia, which reduces risk of injury the longitudinal muscle layer. Additionally, transverse entry incision not only makes it easy to create and pass through the submucosal tunnel and then decrease operation duration, but also facilitates air communication between the esophageal lumen and the tunnel cavity and thus reduction of air pressure in the tunnel cavity. 9.7 % of patients (3/31) underwent POEM with transverse incision experienced pneumatosis-related complications, which was lower than that with longitudinal incision [10]. During operation, vital signs and oxygen saturation should be monitored closely, and periodically physical examination and postoperative immediate X-ray check-up should be conducted for timely detection of pneumatosis.

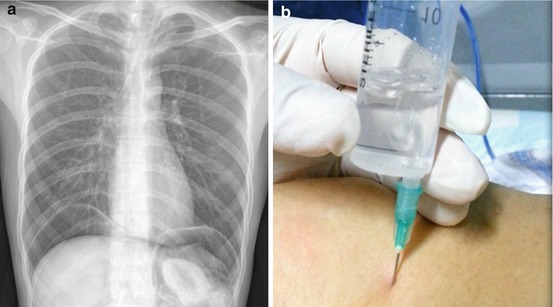

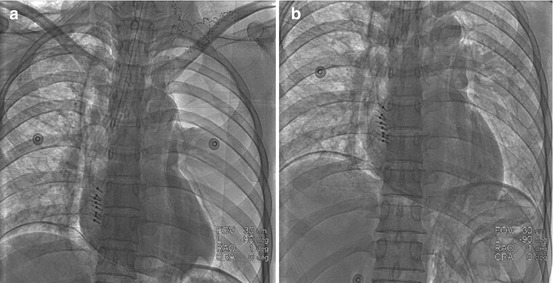

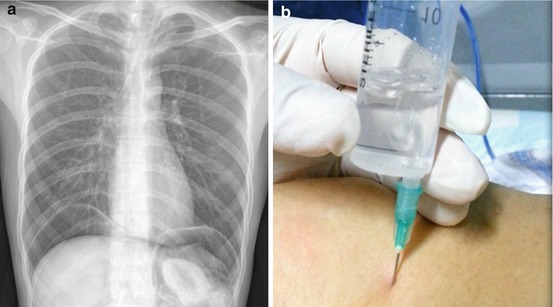

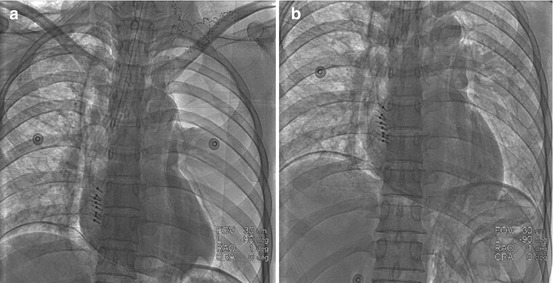

Generally, subcutaneous emphysema, mediastinal emphysema and a small amount of abdominal pneumatosis will disappear spontaneously without special treatment in 2 or 3 days. If the abdomen is obviously distended, abdomen puncture should be performed with an injection needle or a No. 8 needle to decrease abnormal pressure to prevent abdominal compartment syndrome (Fig. 9.1). With regard to a mild closed pneumothorax ( compression volume less than 20 %) without dyspnea, the gas could be absorbed spontaneously without serious adverse events by means of conservative treatment, such as stay in bed with semi-reclining position, ECG monitoring, oxygen inhalation, and administration of antibiotics and PPI inhibitors. High-flow oxygen inhalation can speed up gas absorption and lung recruitment. When the volume of closed pneumothorax is more than 20 % or patients present with obvious dyspnea, thoracocentesis for simple gas exhaust or thoracic close drainage is desperately needed (Fig. 9.2). The tube could be removed, only when there is no pneumothorax recurrence after closing drainage tube for 24 h with confirmed lung re-expansion.

Fig. 9.1

(a) Bilateral subdiaphragmatic free air was detected by X-ray examination after POEM. (b) Abdomen puncture was performed for gas exhaust with a 20 ml injector

Fig. 9.2

(a) After POEM, immediate chest X-ray indicated left pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema in right cervical region. (b) The left lung expanded well after pumping up approximate 300 ml of gas at across the point of anterior axillary line and the third intercostal space

Mucosal perforation also happen occasionally, the incidence of which is 3.6–20 % [6, 7, 10, 11]. It is most likely to occur in GEJ (gastroesophageal junction) because the small operation space and abundant submucosal vessels demanding repeated electrocoagulation make the mucosa vulnerable to excessive coagulation. It is worth noting that injured mucosa by over-coagulation, even if not penetrated, is likely to develop ulcers in case of being ignored (Fig. 9.3). Pleasantly, the mucosa injury or perforation can be easily managed by hemostatic clips or fibrin sealant [11, 12] (Figs. 9.4 and 9.5).

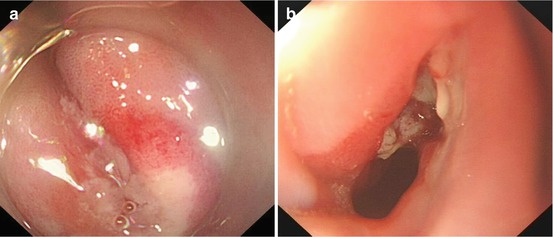

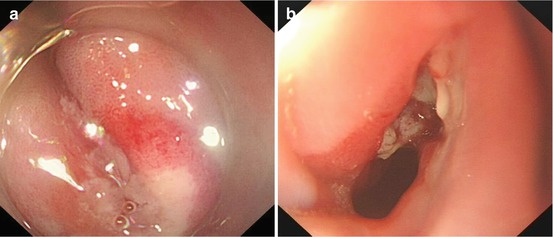

Fig. 9.3

(a) The mucosa was damaged by over-coagulation and turned pale in GEJ. (b) After 7 days, a large deep ulcer developed where the mucosa was damaged

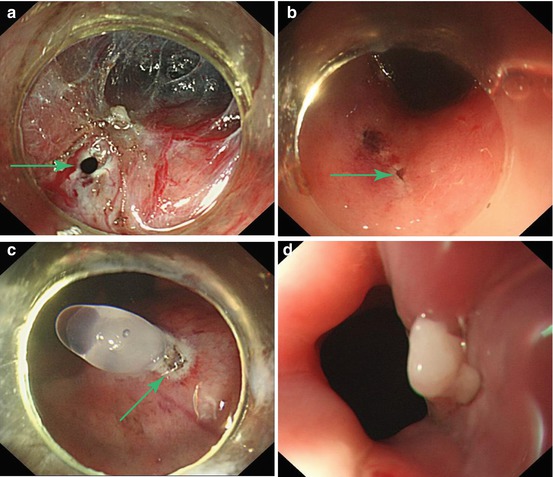

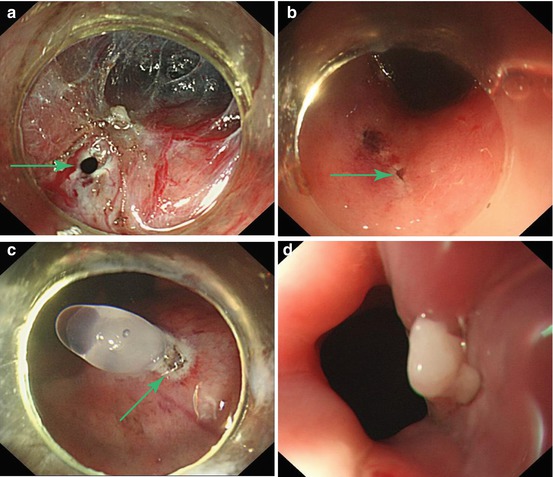

Fig. 9.4

Fibrin sealant for closure of mucosal perforation. (a) The mucosal perforation was seen inside the submucosal tunnel during POEM (arrow). (b) The mucosal perforation was seen outside the submucosal tunnel during POEM (arrow). (c) Fibrin sealant flowed outside from within the tunnel and sealed the perforation (arrow). (d) One week later, the perforation was well sealed (b and d are reproduced with permission from Li et al. [12])

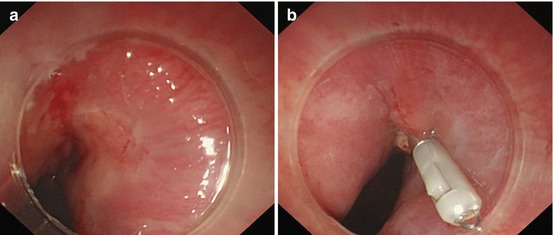

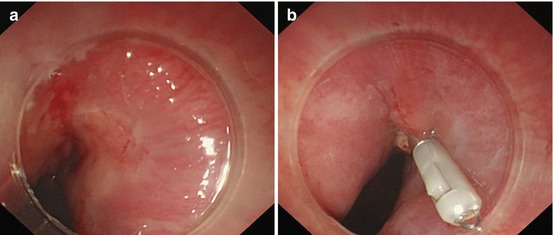

Fig. 9.5

Hemostatic clips for mucosal perforation. (a) Mucosal defect was seen at GEJ. (b) Mucosal defect was clipped successfully

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree