- It is important to be able to identify those with early chronic kidney disease (CKD), firstly because CKD has a very strong association with the risk of death, cardiovascular disease and hospitalization, and secondly, in order to attempt to prevent/delay the progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

- In relation to the management of CKD, important factors to consider are the rate of change of kidney function and whether there is proteinuria or haematuria. The presence of other comorbidities, current or recent drug history, family history and the age of the patient are additional factors that need to be taken into account.

- If estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the first test, retest within two weeks to exclude causes of acute deterioration of glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

- Significant progression of CKD is defined as a decline in eGFR of >5 mL/min/1.73 m2 within 1 year, or >10 mL/min/1.73 m2 within five years.

- All CKD patients should be checked for proteinuria.

- In people without diabetes, albuminuria/proteinuria is considered clinically significant when the albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR) is

30 mg/mmol.

30 mg/mmol.

- In people with diabetes, consider microalbuminuria of an ACR > 2.5 mg/mmol in men and >3.5 mg/mmol in women to be clinically significant.

- A nephrological referral should be considered (a) if there is significant proteinuria (ACR

70, or protein:creatinine ratio (PCR)

70, or protein:creatinine ratio (PCR)  100) with or without haematuria or (b) if the ACR

100) with or without haematuria or (b) if the ACR  30 or PCR

30 or PCR  50 with haematuria.

50 with haematuria.

- If a young adult has haematuria (cola-coloured!) and an intercurrent illness (usually an upper respiratory tract infection), they should be suspected of having acute glomerulonephritis.

- In general, people in stages 4 and 5 CKD, with or without diabetes, should be considered for specialist assessment. However, at an earlier stage, other factors—including proteinuria, haematuria, poorly controlled hypertension, rate of change of eGFR and consideration as to whether the rate of progression of eGFR would make renal replacement therapy likely within the person’s lifetime—would all influence the need for referral.

Introduction

Until recently, the care of kidney patients has been largely under the domain of nephrologists in secondary care. However, the increasing number of people diagnosed with chronic kidney disease (CKD), previously termed chronic renal failure, along with the more active treatment of end-stage renal disease (many more people have access to dialysis now than even a decade or so ago) means that not only has more of the care been streamlined into nurse-led clinics, but the earlier stages of renal disease are now being managed in the community by GPs.

This latter strategy means that an ever-wider group of healthcare professionals is obliged to have an understanding and basic knowledge of issues in relation to patients with CKD. The aim of this chapter is to discuss the prevalence, detection, evaluation and management of this condition.

Prevalence and Staging of Chronic Kidney Disease

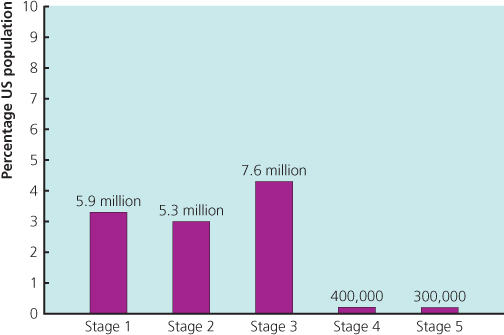

Several epidemiologic studies have indicated that there is a high prevalence of CKD in the general population. The survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States from 1999 to 2004 suggested that up to 16.8% of the adult population have CKD (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2007). Another US study, the National Health and Nutrition Survey (NHANES III), based on data from 15 635 adults and including measurements of creatinine, urine albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR) and estimate glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), estimated that the prevalence of CKD was 11% (equating in 2003 to 19.2 million adults in the United States) (Coresh et al. 2003; Figure 3.1). Data from the United Kingdom suggests a similarly high prevalence of CKD in the general adult population (Anandarajah et al. 2005).

Figure 3.1 NHANES III data showing the prevalence of CKD Stages 1 to 5 in the United States in 2003.

(Source: Coresh et al. 2003.)

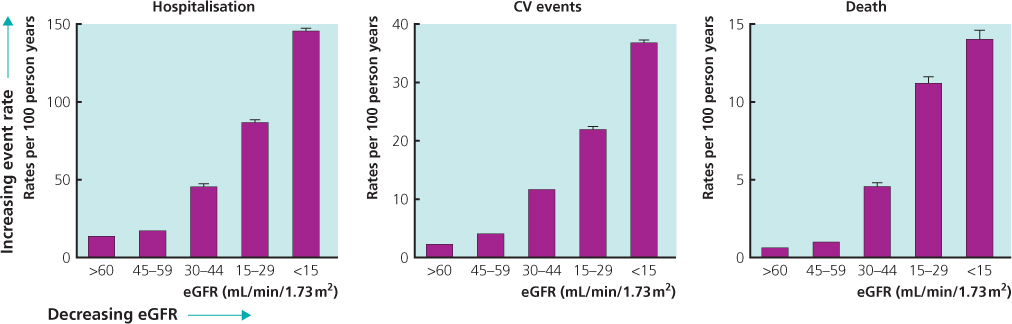

Despite the high prevalence, only a minority of those with CKD will progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (Hallen et al. 2006) and the majority of CKD patients will be identified and managed within the primary care setting. It is important to be able to identify those with early CKD, firstly because CKD has a very strong association with the risk of death, cardiovascular disease and hospitalization (Figure 3.2; Table 3.1), and secondly in order to attempt to prevent/delay the progression to ESRD, which is associated with considerable morbidity and a high mortality (UK Renal Registry 2009), as well as affecting quality of life. Furthermore, costs of ESRD are considerable. In the United Kingdom, the absolute cost per patient is around £30,000–£35,000 per year for haemodialysis patients, and around £20,000–£25,000 per year for peritoneal dialysis patients.

Figure 3.2 Risk of hospitalization, cardiovascular events and death with respect to renal function (eGFR).

(Source: Go et al. 2004.)

Table 3.1 Independent predictive variables for combined endpoints of CV death, myocardial infarction and stroke

Source: Reprinted from The Lancet, HOPE Study Investigators, 2000; 355: 253–259, with permission from Elsevier

| Variable | Hazard Ratio |

| Microalbuminuria | 1.59 |

| Creatinine >123.76 mmol/L | 1.40 |

| CAD | 1.51 |

| PVD | 1.49 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.42 |

| Male | 1.20 |

| Age | 1.03 |

| Waist:Hip ratio | 1.13 |

CAD, Coronary Artery Disease; PVD, Peripheral Vascular Disease.

Source: NICE 2008

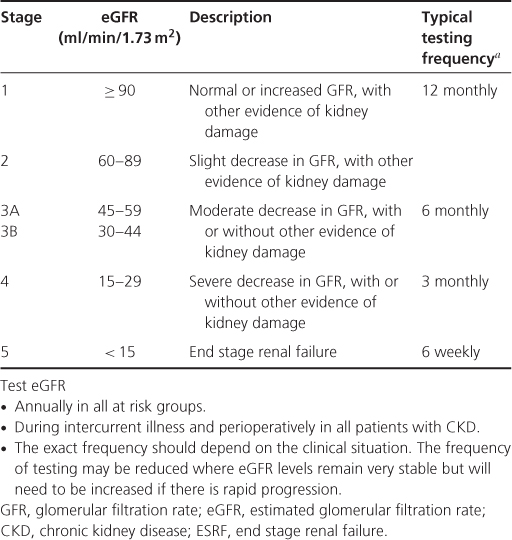

In order to help in the early identification of patients, and enable stratification of risk and management, CKD has been categorized into stages dependent on the eGFR, whether other evidence of kidney damage is present and whether or not there is proteinuria.

In September 2008, the NICE guideline on CKD (NICE 2008) updated the staging of CKD. The previous stage 3 (30–59 ml/min) was subdivided into stage 3A with an eGFR of between 45 and 59 ml/min/1.73 m2, and stage 3B with an eGFR of between 30 and 44 mL/min/1.73 m2. In addition, it is recommended that the suffix ‘p’ be placed after the stage to denote the presence of proteinuria, where proteinuria is defined as urinary ACR  30 mg/mmol or PCR

30 mg/mmol or PCR  50 mg/mmol. The rationale for these changes was an increasing realization that most of the complications associated with CKD showed a rapid increase in prevalence in patients with an eGFR of <45 ml/min, and that the prognosis for patients with proteinuria was very much worse compared to those without proteinuria (Table 3.2).

50 mg/mmol. The rationale for these changes was an increasing realization that most of the complications associated with CKD showed a rapid increase in prevalence in patients with an eGFR of <45 ml/min, and that the prognosis for patients with proteinuria was very much worse compared to those without proteinuria (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2 Stages of chronic kidney disease and frequency of estimated glomerular filtration rate testing (NICE 2008)

Detection

CKD is often asymptomatic in its early stages. Kidney disease may be detected (whether routinely or as part of an investigative procedure) by:

- blood tests for creatinine/eGFR—routine or investigative;

- urine tests for albuminuria/proteinuria/haematuria—may be routine (change of GP, insurance medical, etc.) but also investigative. All hypertensive patients should have urinary ACR checks and urinalysis for haematuria (NICE 2011), while all diabetics should have first-pass urine tests for ACR (NICE 2009);

- family history—for those who have relatives with polycystic kidney disease or other rarer causes of hereditary renal disease (such as Alport’s syndrome);

- renal imaging—in general, renal disease could be picked up by screening for other problems, e.g. coincidentally during ultrasonography for suspected gallstones. Ultrasound may also detect reflux nephropathy in babies in utero, or in the neonate.

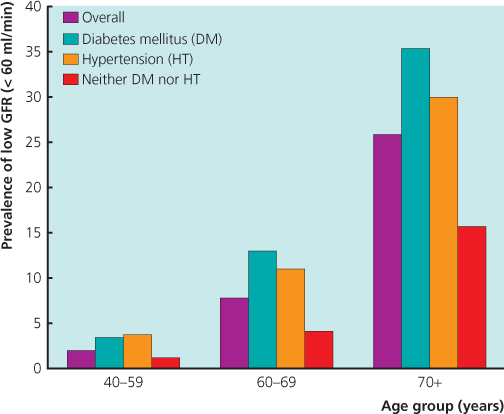

In view of the high prevalence of CKD, it is becoming increasingly necessary to find a means to develop a ‘renal risk score’ in order to help identify those at risk of progressive CKD, as well as those who would benefit from referral to a nephrologist. Unfortunately, although such scores have indeed been devised (Halbesma et al. 2011), none is robust enough to be adopted into routine clinical management (Taal 2011). This is partly because there are a large number of CKD risk factors/markers (Table 3.3), which will affect the sensitivity of a simple, universally applicable scoring system. Over 75% of CKD patients will have either diabetes, hypertension or are aged over 65 years. Data from NHANES III showed about 25% of CKD cases had diabetes, 75% had hypertension, while 11% of all patients over 65 years who did not have diabetes or hypertension had CKD (Figure 3.3). It follows that an increasing prevalence of these factors parallels a proportionate rise in CKD prevalence.

Figure 3.3 Prevalence of GFR < 60 mL/min in relation to age and the presence or absence of DM or HT.

(Source: Coresh et al. 2003.)

Table 3.3 Risk markers/factors for chronic kidney disease

| Non-modifiable | Modifiable |

| Old age (S) | Systemic hypertension (I, P) |

| Male sex (S) | Diabetes mellitus (I, P) |

| Race/ethnicity (S) | Proteinuria (P) |

| Genetic predisposition (S) | Dyslipidaemia (I, P) |

| Family history (S) | Smoking (I, P) |

| Low birth weight (S) | Obesity (I, P) |

| Alcohol consumption (I, P) | |

| Low socio-economic status (S) | |

| Infections/Infestations (I) | |

| Drugs and herbs/analgesic abuse (I) | |

| Autolmmune diseases/obstructive uropathy/stones (I) |

S, Susceptibility factor, I, Initiation factor, P, Progression factor.

According to NICE clinical guideline 73 (NICE 2008), people should be offered testing for CKD if they have any of the following risk factors:

- diabetes

- hypertension

- cardiovascular disease (ischaemic heart disease, chronic heart failure, peripheral vascular disease or cerebrovascular disease)

- structural renal tract disease, renal calculi or prostatic hypertrophy

- multisystem diseases with potential kidney involvement, e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- family history of stage 5 CKD or hereditary kidney disease

- opportunistic detection of haematuria or proteinuria.

Evaluation

For the majority of patients with CKD there is no, or very slow, progression of renal impairment, and only a small percentage reach end-stage renal disease. In relation to the management of CKD, it is first necessary to take a good history, which will include concurrent or recent drug history as well as family history (e.g. for polycystic kidney disease and Alport’s syndrome). Important factors to evaluate also include the rate of change of kidney function and whether there is proteinuria or haematuria. The presence of other comorbidities (such as diabetes, hypertension, SLE) and the age of the patient are additional factors that need to be considered. Even though a decline in GFR with age is normal, there is currently no consensus around which level of GFR is considered ‘normal’ at a certain age. The eGFR takes age into consideration, but does not fully correct for the natural ageing process.

Creatinine/Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

- When checking eGFR, bear in mind ethnicity, weight, age, muscle mass, gender, diet (protein meal) and exercise.

- NICE clinical guideline 73 (NICE 2008) advises the use of the simplified MDRD equation to estimate eGFR. Since eGFR may be less reliable in certain situations (such as acute kidney injury, pregnancy, oedematous states, muscle wasting disorders, amputees and malnutrition), the serum creatinine should be considered as well as the eGFR.

- With Afro-Caribbean or African ethnicity, the eGFR should be corrected by multiplying by 1.21. Validation of the eGFR has not been well established for those of Asian or Chinese ethnicity.

- Caution in eGFR interpretation should be used for people with extremes of muscle mass, for those who have taken creatine supplements, or if the patient performed heavy exercise before their blood test.

- Protein meals or supplements may also affect the eGFR, and meat should be avoided for at least 12 hours before an eGFR blood test.

- If eGFR is <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 in the first test, retest within two weeks to exclude causes of acute deterioration of GFR.

- To identify progressive CKD, obtain a minimum of three eGFR estimations over a period of not less than 90 days. Progressive CKD is defined as a decline in eGFR of >5 ml/min/1.73 m2 within one year, or >10 ml/min/1.73 m2 within five years.

Albuminuria/Proteinuria (also See Chapter 1)

Proteinuria can be glomerular or tubular. Glomerular protein largely consists of albumin, and levels of proteinuria greater than 1 g per day usually indicate glomerular proteinuria, which results from a breakdown in the integrity of the glomerular basement membrane and, more specifically, damage to podocytes in the membrane.

Proteinuria is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and is an independent risk factor for progression of renal disease.

All CKD patients should be checked for albuminuria/proteinuria. This may easily be detected by testing urine using reagent strips, but these are not usually as sensitive as sending the sample to the biochemistry lab for measurement of ACR (albumin:creatinine ratio) or PCR (protein:creatinine ratio). The ACR has greater sensitivity than PCR for low levels of proteinuria and is usually the preferred test, but nephrologists still tend to use PCR more than ACR. The opposite is true among diabetologists, who more commonly use ACR so that they can detect the very earliest stages of diabetic nephropathy, which may be amenable to treatment (Table 3.4).

Table 3.4 Approximate equivalent values of ACR, PCR, and urinary protein excretion

| ACR (mg/mmol) | PCR (mg/mmol) | Urinary protein excretion g/24 hr |

| 30 | 50 | 0.5 |

| 70 | 100 | 1 |

- If the initial ACR is

30 mg/mmol and <70 mg/mmol, a further early-morning sample for ACR should be sent for confirmation. If the initial sample is >70 mg/mmol, no repeat sample is necessary.

30 mg/mmol and <70 mg/mmol, a further early-morning sample for ACR should be sent for confirmation. If the initial sample is >70 mg/mmol, no repeat sample is necessary.

- In people without diabetes, proteinuria is considered clinically significant when the ACR is

30 mg/mmol.

30 mg/mmol.

- However, in people with diabetes, consider microalbuminuria with an ACR > 2.5 mg/mmol in men and >3.5 mg/mmol in women to be clinically significant.

Haematuria (also See Chapter 1)

Haematuria can either be glomerular (from the kidney) or extra-glomerular (from a urological source).

- When testing for haematuria, urinary reagent strips should be used rather than urine microscopy. This is partly because of the lack of availability of access to quality microscopic techniques with skilled operators and partly because of the need for the microscopy testing to be performed on a relatively fresh sample of urine. Dipstick urinalysis has the advantages of simplicity and accessibility.

- Microscopic haematuria is now more aptly termed non-visible haematuria (NVH). This can be subdivided into symptomatic NVH with the presence of lower urinary tract symptoms, or asymptomatic NVH.

- If there is a positive urinary reagent strip test of 1+ or more of blood, confirmation with a reagent strip (as opposed to microscopically) should be made, and further evaluation will be necessary. Trace haematuria should be considered negative.

- Any episode of visible haematuria or symptomatic NVH in the absence of a urinary tract infection (UTI) or transient cause is considered significant. Persistence of asymptomatic NVH (defined as at least two out of three positive NVH dipsticks) is also considered significant.

- Investigate symptomatic and persistent asymptomatic haematuria by (i) excluding UTIs or other transient causes; (ii) checking creatinine/eGFR; (iii) sending urine for ACR or PCR on a random sample [an approximation to the 24-hour urine albumin or protein excretion (in mg) can be obtained by multiplying the ratio (in mg/mmol) × 10]; (iv) measuring blood pressure (BP) (BAUS/RA 2008).

- All patients with significant visible or symptomatic non-visible haematuria, and patients over the age of 40 years with asymptomatic non-visible haematuria, should be considered for urological referral. An exception of referring directly to a nephrologist may be a young adult who has haematuria (cola-coloured!) and an intercurrent illness (usually an upper respiratory tract infection), and who is suspected of having acute glomerulonephritis.

- A nephrological referral should be considered (a) if there is significant proteinuria (ACR

70, or PCR

70, or PCR  100) with or without haematuria, or (b) if the ACR

100) with or without haematuria, or (b) if the ACR  30 or PCR

30 or PCR  50 with haematuria.

50 with haematuria.

- For those with haematuria but no proteinuria, there should be annual testing for haematuria, albuminuria/proteinuria, eGFR and BP monitoring, as long as the haematuria persists. An adult under the age of 40 years with hypertension and isolated haematuria (i.e. in the absence of proteinuria) should be referred to a nephrologist. The two most common causes of this scenario are hypertensive nephropathy and IgA nephropathy.

Non-visible haematuria is seen in 3–6% of the normal population. A recent 22-year retrospective study of over 1.2 million young adults found a substantially increased risk for treated ESRD attributed to primary glomerular disease in individuals with persistent asymptomatic isolated non-visible haematuria compared to those without. However, the incidence and absolute risk of ESRD remains quite low (Vivante et al. 2011).

Renal Imaging (also See Chapter 1)

Renal ultrasound should be offered to all people with CKD who (i) have progressive CKD, (ii) have visible or persistent non-visible haematuria, (iii) have symptoms of urinary tract obstruction, (iv) have a family history of polycystic kidney disease and are over 20 years old, (v) have stage 4 or 5 CKD and (vi) require a kidney biopsy.

More Specialist/Other Renal Screening Tests for Underlying Cause of Chronic Kidney Disease

- There are several complementary different ways to screen for the presence of renovascular disease (which is typically atheroscleroticin most adults)—including MR scanning, CT scanning and Doppler US screening. Check with your local radiology department to see which is favoured for screening. See Chapter 8 for more detailed information.

- Serum immunoglobulins/protein electrophoresis/serum-free light chains may be requested to screen for myeloma.

- Auto-antibodies: ANA, dsDNA, ANCA, anti-GBM antibody. ANA and dsDNA are useful screening tools for SLE and may indicate underlying lupus nephritis as the cause of CKD. Screening for possible vasculitis should include a request for antinuclear cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). Likewise, a positive anti-GBM antibody may indicate underlying Goodpasture’s disease.

- Complement levels both C3 and C4 levels are often reduced in active SLE, and low C3 levels may indicate underlying mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (MCGN).

- Virology several glomerulonephritides may be driven by viruses and other infectious agents (e.g. Hep B, Hep C, HIV). A positive HIV test may suggest underlying HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN), which presents with proteinuria +/− renal impairment and almost exclusively occurs in black people.

- Renal biopsy In patients with renal impairment and/or proteinuria of more than 1 g per day (PCR > 100), a renal biopsy may be required to elucidate the cause of underlying CKD, provided this is technically feasible. (Relative contraindications may be extreme obesity, small kidneys of less than 9 cm, etc.)

- Genetic testing Although two gene mutations (PKD1 and PKD2) have been identified in patients with polycystic kidney disease, the test is not widely available, and its utility remains questionable. There are potentially some instances when this test may be useful (e.g. in a family when the mutation is already known), but widespread adoption of this test is not considered appropriate at the present time.

Management

The management of CKD varies according to the stage of CKD (Figure 3.4) and can be divided into both general and specific measures.

General

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree