Pouchitis

Kim L. Isaacs

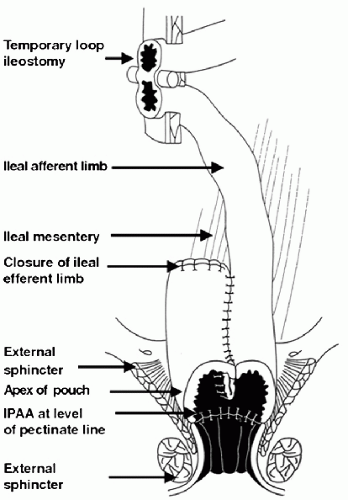

A restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis is the most common surgical procedure performed for patients with medically refractory ulcerative colitis or familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) coli. It is estimated that up to 25% of patients with ulcerative colitis will require colectomy during the course of their disease (1). There is also a population of patients with Crohn’s colitis who have had an ileal pouch inadvertently created and who have subsequently been shown to have a good functional outcome after surgery leading to consideration of this surgery in select patients with refractory Crohn’s colitis (2,3). The surgery involves a total abdominal colectomy and creation of a pelvic reservoir out of ileum that is then sutured to the anal transition zone (4). The preservation of the anal transition zone aids in maintenance of continence after the surgery. The most common type of pouch currently created is the J-pouch configuration (Fig. 16.1). The anastomosis may be a stapled anastomosis that leaves a variable amount of colonic mucosa in the area of the anal transition zone or a mucosectomy with a hand-sewn anastomosis that does not leave rectal mucosa in the area of the transition zone (4). The success of this surgery is dependent on pouch function, which can be impaired by recurrent pouch inflammation. Pouchitis may be seen in up to 60% of patients following a restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis (5). When performed in patients with FAP, pouchitis is less common, occurring in 0% to 11% of patients (6).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The etiology of idiopathic pouchitis is not entirely clear. There appears to be a strong association with bacteria in the pouch and a possible immunologic/genetic component. Pouchitis does not occur until the ileal pouch is exposed to the fecal stream, usually after closure of the loop ileostomy (5). It has been proposed that there are unique patterns of the microflora associated with pouch inflammation (7). There are differences in sulfate-reducing bacteria in pouches of patients with history of ulcerative colitis as compared to those in whom the pouch was created for FAP (8). The mainstay of therapy in the treatment of pouchitis has been the manipulation of pouch bacteria (5).

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

The bowel movement frequency after IPAA varies from person to person with a mean daytime stool frequency of 6.4 and nighttime stool frequency of 2.0 after 20 years (9). Stools tend to be formed with liquid stools described in 12% at 20 years post surgery (9). Approximately 75% of patients will be able to distinguish stool from gas and 70% will not experience any daytime incontinence. Symptoms commonly seen in pouchitis include an increase in stool frequency and liquidity (4). Patients may experience low-grade fever, abdominal cramping, lower back pain, and rectal bleeding. Incontinences both day and night increase during an episode of pouchitis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Patients presenting with disorders of the ileal pouch may not all have pouchitis (Table 16.1). There is a group of patients who will have symptoms suggestive of pouchitis but endoscopically and histologically have no demonstrable inflammation. This disorder has been referred to as irritable pouch syndrome and is likely a motility disorder of the pouch (10). Crohn’s disease of the pouch has been described in up to 13% of patients following IPAA (11). Most of these patients do not have known Crohn’s disease prior to surgery and present with symptoms suggestive of pouchitis. The diagnosis is made endoscopically. There likely is overlap of this entity with pouchitis; however, long-segment inflammation of the neoterminal ileum above the pouch, granulomatous inflammation, and recurrent fistulizing disease would all be suggestive of a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease of the ileoanal pouch (12). Cuffitis is defined as inflammation of the rectal cuff. This is the area of remaining rectal mucosa in the anal transition zone. The inflammatory changes in this area relate to the original disease process. Inflammation in this area may lead to a stricture of the ileoanal anastomosis. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDS) may also contribute to inflammation in the ileoanal pouch. It is unclear if they directly cause pouch inflammation or they exacerbate an underlying pouchitis (13).

TABLE 16.1 Differential Diagnosis of Pouchitis Symptoms | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Withdrawal of NSAIDs in patients with disorders of the ileoanal pouch leads to a marked improvement in overall quality of life and pouchitis disease activity scores (13). Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea has become much more prevalent in the IBD population. Although C. difficile is typically associated with a toxin-induced colitis, it may also affect the ileoanal pouch. Shen and colleagues found that 18.3% of patients undergoing pouch endoscopy had stool aspirates positive for C. difficile toxin (14). Patients with medically refractory ulcerative colitis are receiving a greater degree of immunosuppression prior to colectomy, which raises the potential issue of CMV infection of the pouch post surgery. Primary CMV infection of the pouch has been described and should be considered in patients with refractory pouchitis (15).

ENDOSCOPY

Endoscopic assessment of the pouch with biopsy is indispensable in differentiating the different potential cause of pouchitis symptoms (16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree