Posture

Posture is simply the relationship or alignment between the various parts of the body. It is important from two standpoints. Firstly, good posture underlies all exercise techniques. Your posture is really your foundation for movement. In the same way that a building will fall down if its foundations are shaky, your whole body will suffer if your posture is poor. Exercises which begin from the basis of poor posture tend to be awkward and clumsy. Because of this they are less effective and, more importantly, the person using awkward, clumsy movements is likely to be injured.

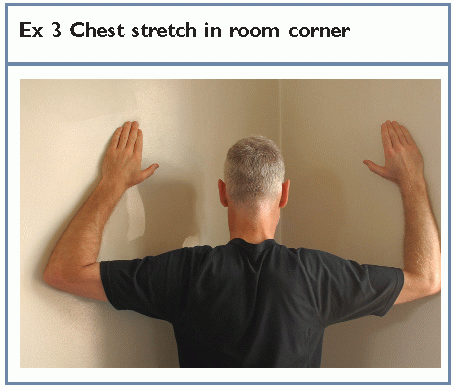

The second important point about posture is that an incorrect posture allows physical stress to build up in certain tissues, ultimately leading to pain and injury. For example, a person who is very round-shouldered may simply have started out with tightness in the chest muscles and weakness in the muscles which brace the shoulders back. If this combination had been corrected at the time, the poor posture may not have built up over the years. As a consequence of poor posture, the way that the joints move will change. Alteration in movement of this type will mean that joints can be subjected to uneven stresses. When this continues over the years, the eventual outcome can be the development of wear and tear (osteoarthritis) in later life.

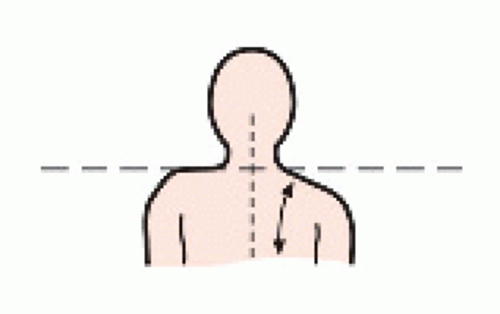

Fig. 4.1 Poor posture: increased stress on portions of the joint and muscles work harder because body segments are out of alignment (b) |

Poor posture then gives two important features. Firstly joint alignment is not optimal so bodyweight, which would normally be distributed quite evenly across the joints, is taken more by one area than another (see fig. 4.1b). This leads to increased stress on portions of the joint. Secondly, good posture is one of balance and very little muscle work is actually needed

to maintain it. With a poor posture the muscles have to work much harder because the body segments are out of alignment (see fig. 4.1b). Increased muscle work of this type often leads to aching and the development of painful trigger points within the muscles.

to maintain it. With a poor posture the muscles have to work much harder because the body segments are out of alignment (see fig. 4.1b). Increased muscle work of this type often leads to aching and the development of painful trigger points within the muscles.

Keypoint

With poor (sub-optimal) posture, stress on the joints is increased and the muscles have to work much harder.

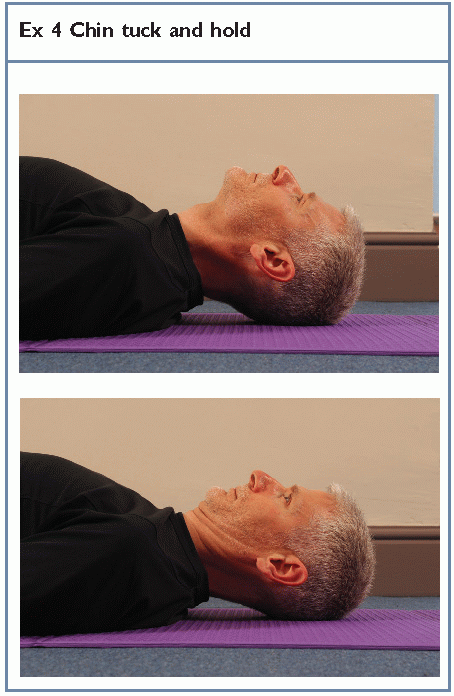

We saw earlier that fitness is really a combination of various components which we called ‘S’ factors. In relation to posture, two of the most important fitness components are flexibility and strength. Postural changes are often associated with poor muscle tone (weakness) in some muscles together with too much tone (tightening) in others. This imbalance in tone gives an uneven pull from the muscles around a joint, and causes the joint to move off-centre (see fig. 4.2). Our aim with exercise is to redress the balance in muscle tone by using stretching exercises to lengthen tight muscles, combined with strengthening exercises to increase the tone of lax muscles.

Fig. 4.2 Posture and muscle imbalance: (a) normal joint – equal muscle tone gives correct joint alignment; (b) postural imbalance – unequal muscle tone pulls joint out of alignment |

Keypoint

Your posture will affect the way you exercise, and the exercises you choose will in turn alter your posture.

Optimal posture

We cannot talk about a normal posture because very few people are ‘normal’ in the true sense of the word. Equally, if we talk about an average posture, the average may be very poor and this type of posture is far from ideal. Instead we should talk about an ‘optimal’ posture, where the various body segments are aligned correctly, and the minimum of stress is placed on the body tissues. This type of posture requires little

muscle activity to maintain it because it is essentially balanced.

muscle activity to maintain it because it is essentially balanced.

The various segments of the body work together like the links in a chain. Movement in one causes movement in the next link which is then passed on to the next, and so on. This means that a postural change in one part of the body can alter the alignment of another body part quite far away. Alterations in the feet are a good illustration of this point. Flat feet (see fig. 4.3), where the inner arch of the foot moves downwards, will in turn twist the shinbone and then the thighbone. Eventually these changes can be felt in the lower back, chest and neck. Because of this intimate link between body segments, it is important to correct any postural fault, however minor it may seem at the time.

Keypoint

In an optimal posture the body segments are correctly aligned, so very little effort is needed to maintain the position.

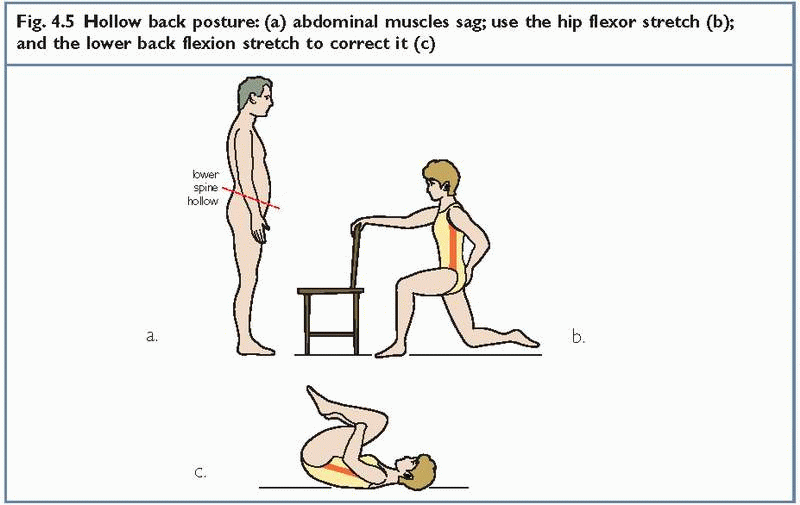

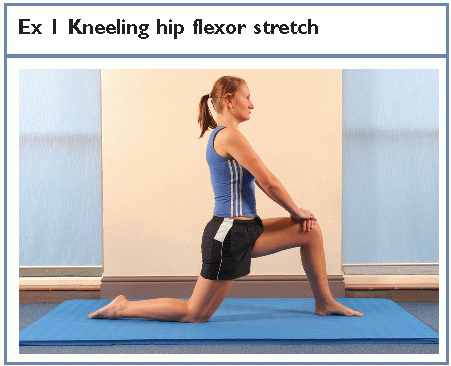

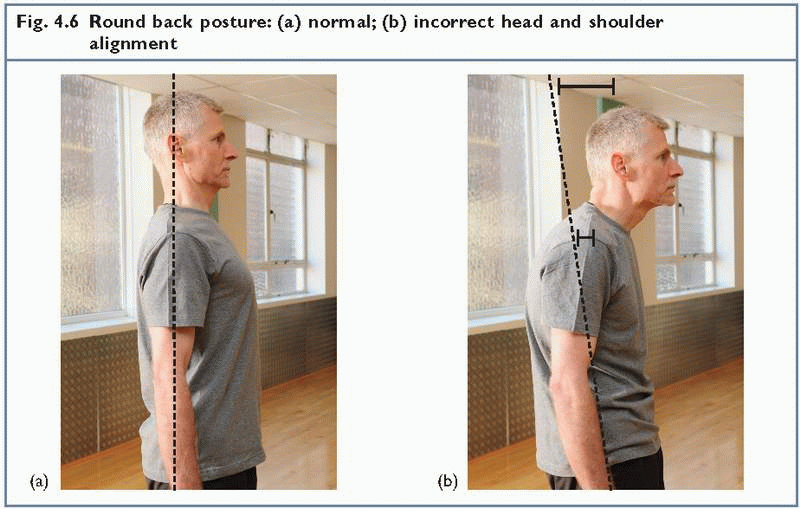

One method of looking at posture is to compare it to the posture line. In an optimal posture this line is similar to a plumb line dropped vertically downwards from the top of the head. The body should be evenly distributed along this line (see fig. 4.4), and ideally the line should pass just in front of the knee joint, travel through the hip and shoulder joints and through the ear. Looking more closely at the pelvis, optimal pelvic alignment occurs when the front lip of the pelvis (anterior superior iliac spine) is in a direct vertical line with the pubic bone in the groin. In this position there should be a gentle curve to the lumbar spine and also to the neck. However, various alterations occur from this normal posture line which we need to consider.

Assessing your own posture

Before you can correct posture using the programme in this book, you must determine your current body alignment. Discovering your personal posture acts as a baseline against which

to measure improvement as you go through the various exercises. You will need to work with a partner; they will assess your posture and you in turn will assess theirs. Ask your partner to stand against a straight vertical edge, such as a doorframe, or plumb line attached to a hook. Make sure that the edge of the line is slightly in front of their anklebone (lateral malleolus) and then compare their posture to this reference line. Fig. 4.4 shows the posture line, together with the optimal alignment. Photocopy this diagram, and then mark on the sheet the positions of their knee, hip, shoulder and ear. It is the centre point of each of these that we are interested in. The next step is to determine the position of your partner’s pelvis. Draw an imaginary line from the furthest point forwards on the rim of their pelvis (anterior superior iliac spine) to their pubic bone. Determine whether this line is vertical or positioned at an angle.

to measure improvement as you go through the various exercises. You will need to work with a partner; they will assess your posture and you in turn will assess theirs. Ask your partner to stand against a straight vertical edge, such as a doorframe, or plumb line attached to a hook. Make sure that the edge of the line is slightly in front of their anklebone (lateral malleolus) and then compare their posture to this reference line. Fig. 4.4 shows the posture line, together with the optimal alignment. Photocopy this diagram, and then mark on the sheet the positions of their knee, hip, shoulder and ear. It is the centre point of each of these that we are interested in. The next step is to determine the position of your partner’s pelvis. Draw an imaginary line from the furthest point forwards on the rim of their pelvis (anterior superior iliac spine) to their pubic bone. Determine whether this line is vertical or positioned at an angle.

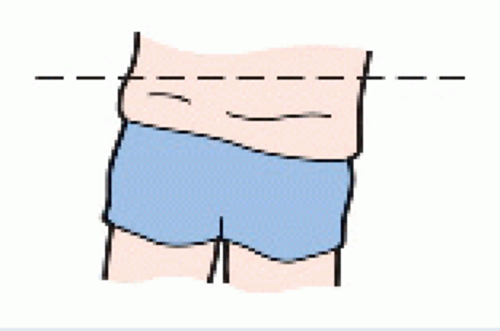

Once you have assessed your partner’s posture from the side, turn them around so that their back is towards you. Their feet should be about 10 cm (4 inches) apart. We will now continue the postural assessment using Table 4.1. Start by looking at their feet. The inner edge of the foot should have a gentle arch, and should not be flat. Moving up the leg, the Achilles tendon should be vertical and the bulk of the calf muscles (gastrocnemius and soleus) should be equal. The creases on the back of the knees (popliteal crease) and the lower edge of the buttocks (gluteal fold) should be on the same level for both sides of the body. The pelvis itself should be level horizontally and the spine aligned vertically. One of the ways that spinal alignment can be checked is to look at the skin creases on either side of the lower trunk; they should be equal in number and shape. The shoulder blades should be about three finger-breadths (6-8 cm) apart, and they should lie on the same horizontal line. The contours of the shoulders should be on the same level and they should appear similar in size and shape. Finally, the head should be level and not tilted to one side. Record any changes from the optimal posture on a photocopy of Table 4.1.

The final method of posture assessment is to establish the depth of the curve in the lower back. Ideally, the curve should be gently hollow. When it is too deep, or too flat, the alignment of the lumbar region changes, indicating that the pelvic tilt is no longer correct. Assess the depth of the lumbar curve by standing with your back up against a wall. Stand with the feet 15-20 cm (6-8 inches) from the wall and the buttocks and shoulders touching the wall. Have your partner slide their hand between the wall and the small of your back. Ideally they should be able to push the hand through the gap only as far as the fingers. If the whole hand passes through, your lumbar curve is too deep. If they can only get the tips of the fingers between your back and the wall, the lumbar curve is too flat.

Summary

In an optimal posture:

the hip, shoulder and ear lie in a vertical line;

the pelvis is level;

the lower spine should be gently hollowed;

the inner edge of the shoulder blades are 6-8 cm (3 inches) apart.

General principles of postural exercise

To modify posture using exercise therapy, we must stretch tight muscle to allow correct movement to take place. If we simply try to exercise against a tight muscle it becomes self defeating – the exercise tries to move the body in one

direction and the body simply pulls back! Once we have stretched and free movement is possible, we now shorten lax muscle. This has the effect of holding the body part in the correct position. Stretching and strengthening (muscle shortening) in this way begins to correct the muscle imbalance which is usually the key feature of postural changes. However, changing the body tissues in this way will allow us to move correctly, but we still may not choose to do so. This is because the sub-optimal posture has been present for some time so it has become familiar – a bad habit if you like – hence the term habitual posture. To modifiy this, we must continually practise correct exercise postures so that we rehearse optimal posture and break our bad habits.

direction and the body simply pulls back! Once we have stretched and free movement is possible, we now shorten lax muscle. This has the effect of holding the body part in the correct position. Stretching and strengthening (muscle shortening) in this way begins to correct the muscle imbalance which is usually the key feature of postural changes. However, changing the body tissues in this way will allow us to move correctly, but we still may not choose to do so. This is because the sub-optimal posture has been present for some time so it has become familiar – a bad habit if you like – hence the term habitual posture. To modifiy this, we must continually practise correct exercise postures so that we rehearse optimal posture and break our bad habits.

Table 4.1 Assessing standing posture from behind | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree