Risk Factors

Geographic distribution: association with smoking and alcohol. There are several high-incidence regions throughout the world; however, the likely major predisposing cause varies markedly from one to the other. These areas include northwestern France, northern Italy, parts of southern and eastern Africa, and southern Brazil as well as the Asian belt stretching from Iran through Afghanistan to central China. The incidence varies from about 30 to 200/100,000 with a strong male predominance of up to 6:1.

12,

13 In these regions, esophageal cancer is usually the most prevalent cancer and results in 30% of all cancer-related deaths. The comparable figure for North America and remaining Europe does not exceed 8/100,000.

14

Smoking and alcohol drinking appear to be the major risk factors with dose-response.

15,

16,

253 Several studies have suggested that smoking increases the likelihood of developing squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus two to six times.

14,

17,

18 Chewing tobacco may well be as harmful as smoking it, and in India it seems to be associated with about a threefold increase in the disease. In Africa, North America, and the rest of Europe, it is quite unusual to encounter squamous cell carcinoma in patients who are not heavy drinkers.

17 This association is independent of tobacco use; in France, alcohol alone seems to be the major predisposing factor.

Although much work has been done on dietary factors, the major etiologic links seem to be with opium in Iran and possibly in the Transkei region of Africa. In Iran, households with a patient having esophageal cancer have much higher levels of urinary opiate metabolites than control households from the same village.

19Diet. A variety of dietary deficiencies resulting from malnutrition have been postulated as predisposing to esophageal cancer, including deficiencies in vitamins A, C, E, and riboflavin, as well as in trace elements such as zinc and molybdenum; indeed these have been postulated for the weak association with celiac disease. A low-protein or low-calorie diet is a possible risk factor. Indeed, increased consumption of meat, eggs, and increased BMI have been reported to be protective factors for squamous cell carcinoma.

20 In high-risk areas of China, drinking shallow ground water and frequent intake of pickled vegetables and fermented fish sauce are associated with the development of esophageal cancer.

16,

21 Consumption of fresh fruits and fresh vegetables may decrease the risk.

16,

20,

21 Although drinking of very hot beverages, which causes thermal injury leading to chronic esophagitis, has also been proposed, these beverages are not associated with risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma in a Western population.

22

Genetic factors. Family history of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is a risk factor for this disease.

23,

24 A meta-analysis using data from three case-control studies conducted in Italy and Switzerland shows that the alcohol- and tobacco-adjusted odds ratio for a family history of esophageal cancer was 3.2 in first-degree relatives; an odds ratio is more than 100 for subjects who currently intake both tobacco and alcohol and

also have the family history.

24 The risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is increased in subjects with a family history of cancer of the oral cavity/pharynx and stomach, but not of other cancers.

24

Human papillomavirus infection. Although human papillomavirus (HPV) is well known to be strongly associated with dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix, its role in esophageal cancer is controversial. In high-risk areas of China, the incidence rate for HPV in squamous cell carcinoma tissue is 17% by in situ hybridization and 65% by polymerase chain reaction.

25,

26 Further analysis in the latter study shows that the high-risk HPV type 16 and 18 are found in the cancer cells (43%), whereas the low-risk HPV type 6 and 11 are seen mainly in the normal mucosa (52%).

25 HPV and p16 silencing may have an etiologic role in esophageal carcinogenesis at least in the high-incidence areas such as China, Korea, Iran, and Greek.

25,

26,

27,

28,

29. The silencing of p16 was reported also from the United States.

30 However, conflicting results with the incidence rates of 0 to 5% have been reported mainly from Western countries.

31,

32

Other risk or protective factors. Free silica dust is suggested to be a possible etiologic factor of esophageal cancer. Among caisson workers who had a higher exposure to silica dust, the relative risk of esophageal cancer has been reported to be more than four and significantly high even after adjusting for the effects of smoking and alcohol drinking.

33 In contrast, chronic intake of rofecoxib and celecoxib (selective cyclooxygenase 2 [COX-2] inhibitors) and nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) appears to be associated with a decreased incidence of esophageal cancer.

34 A randomized control trial suggested that selenomethionine, a synthetic form of organic selenium, might have a protective effect.

35 Infection with

Helicobacter pylori may reduce the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma, but gastric atrophy and infection with CagA-positive strains may increase the risk for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

36

Premalignant Lesions: Dysplasia and Intraepithelial Neoplasia

In three major high-risk populations, those of Iran, China, and South Africa, the sequence of events seems to consist of basal cell hyperplasia, dysplasia, and carcinoma. Further change includes esophagitis, which tends to affect the middle and lower esophagus while sparing the gastroesophageal junction, suggesting that it may not be reflux associated, as the latter is usually in continuity with the gastroesophageal junction. Endoscopic esophagitis is seen in about 85% of all high-risk populations and is already present in some persons in their teens. However, in over half of the patients, the esophagitis is endoscopically mild, and severe changes are seen in only a small percentage. A recent study adjusting for potential confounding factors reported that esophagitis was not a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma.

43 In this study, relative risks for the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma, by initial histological diagnosis, were normal 1.0, esophagitis 0.8, basal cell hyperplasia 1.9 (95% CI 0.8-4.5), mild dysplasia 2.9 (1.6-5.2), moderate dysplasia 9.8 (5.3-18.3), severe dysplasia 28.3 (15.3-52.3), and carcinoma in situ 34.4 (16.6-71.4), during the follow-up period of 13.5 years after endoscopy. Some patients have lesser degrees of dysplasia and sometimes no evidence of dysplasia on follow-up; in these patients, it is unclear whether this

represents regression or sampling problems. Dysplasia in other sites such as uterine cervix is known to regress, and the esophagus may be no exception. Mild dysplasia appears more likely to regress than severe dysplasia, but all degrees of dysplasia may remain stable over considerable periods of time.

44It has long been recognized that the mucosa immediately adjacent to squamous cell carcinoma may show dysplasia or in situ carcinoma.

45,

46 The expression of p53 protein gradually increases from 12% in normal mucosa to 36% in low-grade dysplasia, and 100% in high-grade dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma.

47 These observations strongly suggest that dysplasia and carcinoma in situ are precursor lesions. Caspase-3, TRAIL, Fas-L, Fas, Smad 4, VHL, E-cadherin, and EGFR may be involved in the progression from dysplasia to invasive esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

48 Dysplasia is more frequently found in the mucosa adjacent to early mucosal cancer than with advanced cancer invading into the adjacent structures. This suggests that it is destroyed by the invasive component as the tumor grows. The relatively widespread nature of the dysplasia in some patients was reflected by the fact that when the tumor was limited to the muscularis propria, both proximal and distal margins were involved in 71%.

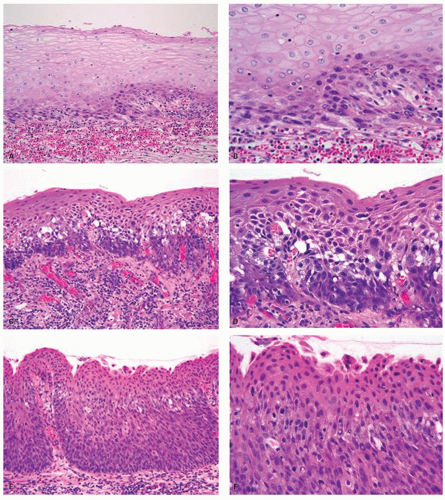

45Dysplasia is defined morphologically by the presence of atypical cells that always include the basal layer and extend throughout varying portions of the thickness of the mucosa. The atypical cells are invariably hyperchromatic with an increase in nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, but the chromatin may be chunky and distributed irregularly throughout the nucleus.

One or more nucleoli are often visible. The common form of dysplasia is composed of atypical basal-type cells that are often monomorphic and is most easily recognized in practice. Pleomorphism, loss of polarity, and sometimes atypical mitotic figures are the major features by which this type of dysplasia is distinguished from simple basal cell hyperplasia associated with reflux or other injuries. An endoscopic “front,” meaning the border between atypical and normal epithelium, is a useful endoscopic sign of dysplasia rather than reactive change. Histologically, in some biopsies, the dysplastic epithelium shows variable extent of maturation and can resemble normal squamous epithelium, except for the dysplasia in the basal layer that can be quite subtle and extremely difficult to recognize. The nuclear atypia, loss of polarity, and dyskeratosis are often subtle, but present. The presence of normal epithelium, if any, in the same slide for comparison is of great help.

Dysplasia or intraepithelial neoplasia had been graded into mild, moderate, and severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ. In this system, dysplasia affecting only the lower third of the epithelium is called

mild; dysplasia extending up to two-thirds of the epithelium is called

moderate; dysplasia reaching into the upper third of the epithelium is called

severe or

carcinoma in situ (

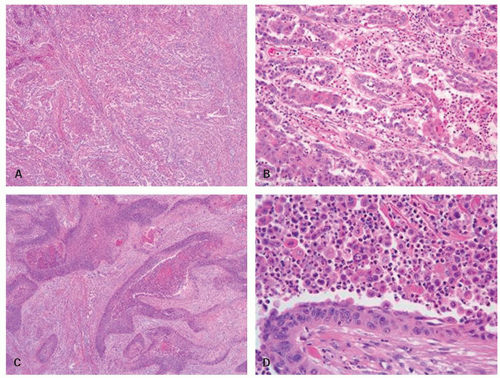

Fig. 11-1). It is interesting that in glandular mucosa the dysplasia is usually at the surface initially in most examples, with only a small proportion being “bottom up,” while in squamous mucosa the dysplasia always begins in the basal epithelium. In the esophageal squamous mucosa, some prefer not to use the term

carcinoma in situ when surface maturation is present. However, severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ have equivalent relative risks for incidence of squamous cell carcinoma, and thus they may have the same clinical implications.

43,

49 To improve the comparability of research data, it has been recommended to use the terms

low– and

high-grade dysplasia (intraepithelial neoplasia),

49,

50 and this system has been employed in the WHO classification from 2000,

51 as well as in the 2010 version. The abnormal cells in low-grade dysplasia are usually confined to the lower half of the epithelium, whereas those in high-grade dysplasia occur in the upper half of the epithelium and exhibit a greater degree of atypia. The distinction from reactive changes is discussed subsequently.

In Japan, carcinoma in situ has morphologically also been divided into two types as total-layer type or basal-layer type.

52,

53In the total-layer type, the full thickness of the epithelium is involved by atypical cells and would be called carcinoma in situ in all other classification schemes. The basal-layer type comprises atypical cells that are present only in the lower half of the epithelium, which would be classified as low-grade dysplasia by Western criteria. However, it appears that the basal-type more often shows signs of early stromal invasion and progression to invasive carcinoma compared to total-layer type.

52

Gross and Endoscopic Appearances

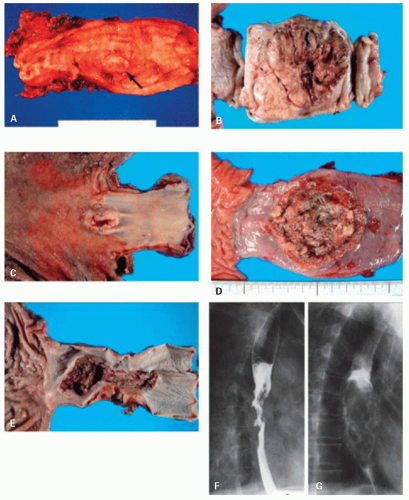

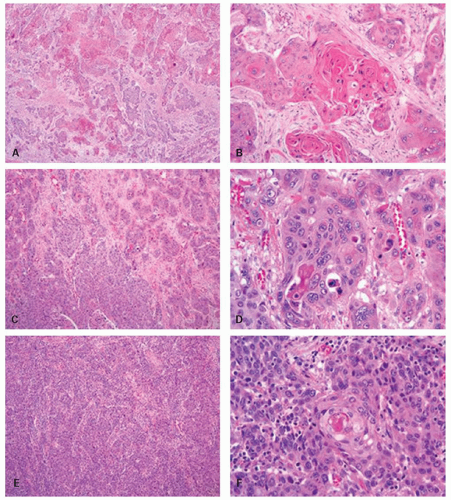

Esophageal carcinomas are typically advanced when diagnosed. Advanced cancers are macroscopically classified into three major types: fungating, ulcerative, and infiltrating. Fungating tumors are well-demarcated lesions with primarily exophytic growth and are less likely to be deeply infiltrating, at least in early stages (

Fig. 11-2). Ulcerative tumors are predominantly intramural, with a central ulceration and elevated ulcer edges. These two types are the most common, forming 60% of tumors in some series.

54 Infiltrating tumors are the least common (15%), but there is tremendous overlap between these groups of tumors. Most tumors infiltrate through the muscularis propria into the adventitia and frequently into adjacent organs, especially in the infiltrating gross variant.

54 Barium swallow may roughly predict the depth of tumor invasion. In one

series, rates of complete resection were 90% in tumors with no deviation of the axis on the barium swallow, 74% in those with deviation of the axis and with partial or complete response to chemoradiotherapy, and 51% in those with deviation of the axis and with no response to chemoradiotherapy, respectively.

55Invasive tumors limited to the mucosa or submucosa and with or without lymph node involvement were originally called superficial carcinomas by the Japanese authors,

56 and this concept is now generally accepted.

57 The definition of early esophageal carcinoma is different from that of early gastric carcinoma in Japan. The former is confined to mucosal carcinoma without lymph node metastasis, while the latter includes also submucosal carcinoma; this difference in the definition reflects a considerable prognostic difference in submucosal carcinoma.

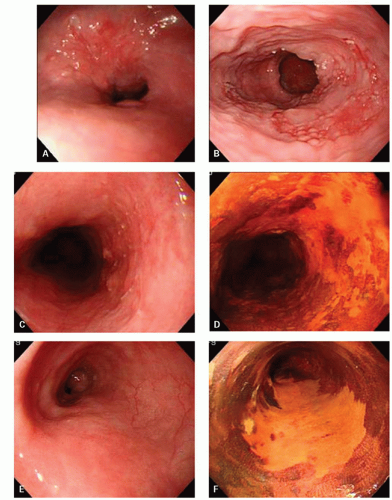

Superficial carcinomas may appear papillary, protruding, plaque-like, erosive, or ulcerated, and sometimes may be invisible (flat), grossly or endoscopically, or may appear as a mucosal granularity, with or without erosions grossly (

Fig. 11-3).

56 The detection of these lesions, as well as of carcinoma in situ, is enhanced by the use of Lugol’s dye spray chromoendoscopy; both fail to stain, in contrast to the normal mucosa, which stains strongly because of its high glycogen content.

57 In one series, standard endoscopy and chromoendoscopy detected 55% and 100% of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, respectively.

58 Confocal endomicroscopy and narrow-band imaging has also been used to facilitate the detection of early lesions.

59,

60 However, endoscopic diagnosis of submucosal invasion is not easy even if using high-resolution endosonography (EUS); sensitivity for submucosal tumors is around 50%.

61Submucosal extension of tumor may be marked in all forms of esophageal carcinoma and occurs

primarily proximal to the tumor, particularly in the submucosal esophageal lymphatics. This has particular relevance at resection because it may be detected only microscopically. Frozen section of the proximal margin is advocated in all patients in whom, should unexpected submucosal tumor spread be found, the resection can be extended proximally. If submucosal tumor extension is marked, it may fill out the submucosal lymphatics to such a degree that they may resemble varices radiologically. This appearance has been termed varicoid carcinoma.

62 Endoscopically, there is little room for confusion because the bluish hue and softness of varices are not apparent.

Multiple tumors are encountered in about 15% of patients.

40,

57 They may reflect either proximal submucosal tumor metastasis with ulceration of the overlying epithelium or truly multiple primaries. It can be argued that such metastases should lack dysplasia or carcinoma in situ in the immediately adjacent mucosa, but coincidental dysplasia or even intramucosal spread of carcinoma can never be entirely excluded, although the latter is quite rare. If small submucosal metastases are examined following radiotherapy, ulceration of the overlying epithelium may be seen. Such ulcers heal following the full course of radiotherapy, causing regression of the underlying tumor. This has been called the Ebb effect.

63When an esophageal cancer is diagnosed endoscopically unless there are known metastases and particularly if surgery is being contemplated, then the patient should undergo an EUS to stage the extent of local invasion.

Spread of Tumor, Staging, and Prognosis

Esophageal carcinoma presenting with symptoms has a very poor prognosis, because its clinicopathological characteristics include the frequent presence of intraepithelial spread, blood vessel and lymphatic permeation, and consequently intramural and lymph node metastasis. Widespread lymphatic dissemination can be present at the time of exploratory thoracoceliotomy even in individuals who do not appear to have metastatic disease clinically. In one series, all of the patients with carcinoma of the lower third of the esophagus and approximately 45% of those with carcinoma of the middle third had celiac node involvement.

66 A major factor in the high mortality of this disease is that 30% to 40% of patients have evidence of advanced local or metastatic disease at presentation; in one series the mean time from first symptoms to autopsy was 10.6 months,

67 although there are increasing data that chemoradiotherapy, particularly that includes cisplatin, can cause considerable shrinkage of tumor, and sometimes prolonged remission even in advanced tumors. The introduction of preoperative chemoradiotherapy resulted in more curative (R0—no residual disease) resections, increasing from 63% to 78% to 79% to 94% of patients.

2,

4,

7 However, a meta-analysis across six studies showed that neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery had only a small, nonstatistically significant trend toward improved survival.

6 Even after R0 resection, overall 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates are 91%, 54%, and 41%, respectively; the pattern of recurrence is local in 12%, regional in 21%, and distant in 20%.

68 The perioperative mortality for esophageal resection was on the order of 10 ± 5% in the past but is now 1.2% to 6% in many recent reports, although this does depend on patient selection.

2,

4,

7,

10,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73TNM classification. Posttherapy pathologic stage was the best available predictor of outcome for patients with esophageal carcinoma.

74 The depth of invasion and the presence of nodal or distant metastases are independent predictors of survival, and these are reflected in the recent TNM classification, being the most widely used staging system. The classification is summarized as follows:

T0 is high-grade dysplasia (see previous discussion— includes the former carcinoma in situ)

T1 invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae (T1a) or submucosa (T1b)

T2 invades the muscularis propria

T3 invades the adventitia

T4 invades adjacent structures (Pleura, pericardium or diaphragm—T4a), or other adjacent structures (e.g., aorta, vertebral bodies, trachea, etc., T4b)

Lymph nodes and distant metastases are classified as negative (0), positive (1), or inaccessible (x),

for example, NO (no regional metastases), N1 (1-2 positive nodes), N2 (3-6 positive nodes), N3 (7 or more positive nodes), MO (no distant metastases), Ml (distant metastases, or unknown NX, MX).

75Local spread and prognostic factors

T Stage The most important factor for prognosis is the histopathological extent of tumor spread. Advanced T stage is a factor predictive of recurrent disease and an independent prognostic indicator.

8,

68,

76,

77 After R0 resection with histologically node-negative (pN0), the survival for patients with T2 or T3 tumors is significantly worse than for those with Tis or T1 tumors.

8 T1 tumors with and without lymph node involvement have a 5-year survival in excess of 60% and 75%, respectively.

78,

79,

80 Intraluminal polypoid or pedunculated tumors and verrucous carcinomas are particularly likely to be in this group.

81 Lymph node metastasis is rarely found in tumors limited to the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae, but occurs in about 40% of tumors invading the submucosa.

64,

80,

82 (See also subsequent section on superficial esophageal carcinoma.) In T2 and T3 tumors, the 5-year survival rate drops to 30% and 10%, respectively

83; however, these rates are more than 50% and 30% in patients successfully undergoing R0 esophagectomy with 3-field lymphadenectomy.

69 The tumor size is an additional independent predictor of mortality when controlling for depth of invasion in patients with localized disease.

3,

84 In one series, cause-specific 5-year survival is 51% for tumors ≤3 cm in diameter, 32% for 3.1 to 4 cm, and 16% for 4.1 to 5 cm; no patient with a tumor ≥6 cm survived.

85

Lymphovascular invasion allows nodal metastasis and hematogenous dissemination and thus results in a frequent tumor relapse and a poor prognosis.

77 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-C may play a role in tumor progression via lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis.

86 Lymphatic invasion is an independent prognostic factor; in one series the 5-year survival rate in patients with lymphatic invasion is 11.1%, compared with 46.6% in those without the invasion.

87

Intramural metastases, probably via a lymphatic duct, are associated with an advanced stage of disease and with a shorter survival.

Radial margin There is some evidence that the presence of tumor within 1 mm of the circumferential margin following potentially curative resection is an important prognostic factor

88 and that a wide proximal margin of excision of at least 10 cm and extensive radical lymphadenectomy may improve survival.

89

Lymph node metastasis indicates a poor prognosis; 5-year survival is 80% and 25% for node-negative and positive patients, respectively.

69 Recent studies have also demonstrated that both the number of positive lymph nodes and the ratio of positive to negative lymph nodes have a prognostic significance.

76,

84,

90 The 2009 CAP guidelines divide these into

_____ pN1: Regional lymph node metastasis involving 1 to 2 nodes

_____ pN2: 3 to 6 nodes involved

_____ pN3: 7 or more nodes involved

In patients with T3 tumor, 5-year survival rates for those without, those with pN1 or pN2 or higher stage are approximately 50%, 30%, and 10%, respectively.

90 Because there is no significant correlation between lymph node size and the frequency of nodal metastases, evaluation of the nodal status is entirely based on histologic analysis.

91 For accurately defining pN category, it is recommended that more than 12 nodes should be examined histologically.

92 Another study from the United States suggested a minimum number of 18 lymph nodes to be examined in such cases.

93Immunohistochemical detection of lymph node micrometastasis may be an indicator of lymphatic dissemination of tumor cells, but is not associated with recurrence-free survival rate.

8,

77Effect of chemotherapy and irradiation. There is an increasing trend toward preoperative chemoradiotherapy, particularly with regimens employing cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil, since patients with squamous cell carcinoma tend to have better progression-free survival with this therapy than those with nonsquamous tumors.

94 A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed that preoperative chemoradiotherapy is associated with a lower rate of esophageal resection but a higher rate of complete resection, and that this therapy does not increase treatment-related mortality.

5 However, chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery does not significantly improve overall survival for patients with advanced esophageal cancer compared with surgery alone,

3,

5,

6,

73,

94 although patients down-staged to pathologic stage 0 or I have a longer survival than those patients who were not downstaged.

73 Note that esophageal biopsy after chemoradiation therapy is not a sensitive (sensitivity 23%) predictor of residual cancer following esophagectomy.

95 The prolonged survival in responders is evident also in chemotherapy plus surgery; 5-year survivals for complete responders, nonresponders, and patients with surgery alone are 60%, 12%, and 26%, respectively.

4 Radiation therapy is very effective for tumors limited to the mucosa and considered to be an alternative modality when endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or surgical treatment cannot be available.

96 However, chemoradiotherapy should be considered for patients with tumor invading into the submucosa, since recurrences are noted in 30% of these patients treated by irradiation alone.

96

2009 CAP guidelines suggest the following for assessment of treatment effects (http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/committees/cancer/cancer_protocols/2009/Esophagus_09protocol.pdf):

No viable cancer cells |

0 (Complete response) |

Single cells or small groups of cancer cells |

1 (Moderate response) |

Residual cancer outgrown by fibrosis |

2 (Minimal response) |

Minimal or no tumor kill; extensive residual cancer |

3 (Poor response) |

DNA ploidy. The nuclear DNA ploidy is determined by flow cytometry or image analysis. In patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, diploid DNA histogram patterns are usually observed not only in cancer cells but also in nonpathologic tissues, either distant or proximal to the lesion.

97 Aneuploidy of cancer cells is identified in 55% to 95%, but not statistically associated with the differentiation of the tumor.

97,

98 It has been suggested that early malignant changes in the esophagus are already associated with alteration in DNA content, and that aneuploidy tends to correlate with progression to invasive cancer; in one series, aneuploidy was observed in 63% of early carcinomas and 91% of advanced carcinomas.

97 However, it is unclear whether ploidy status represents an independent variable for prognosis. A prognostic impact independent of tumor stage has been shown only in a few studies,

99,

100 whereas the majority of studies have not verified this finding.

98 One study suggested that aneuploid tumors may be more sensitive to chemoradiotherapy with hyperthermia.

101

Molecular factors as prognosticator. There is growing evidence that preoperative genetic assessment of biopsy specimens provides useful information concerning selection of treatment modalities. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy is a recent trend and pathologic complete responders have a significant better 5-year survival rate compared with nonresponders. The good response to this therapy has been suggested in tumors with strong expression of 14-3-3 sigma (one of the p53 family proteins) or CDC25B, while expressions of p53, metallothionein, and COX-2 are associated with the poor response.

102 The combined evaluation of these biomarkers may therefore help to identify patients who will benefit from chemoradiotherapy.

103,

104,

105

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) such as MMP-2, MMP-7, MMP-9, stomelysin-3 (MMP-11), and MMP-13 have been thought to function in an early stage of squamous cell carcinoma.

106,

107 The expression of MMP-9 is mainly found in cancer cells at the invasive front and is positively correlated with existence of vessel permeation and lymph node metastasis.

107,

108 Regarding the prognostic impact, the coexpression of MMP-7, MMP-9, and MMP-13, and the combined phenotype of positive stomelysin-3 and negative tissue inhibitors of MMP-2 may be adverse prognosticators for relatively early stage tumors.

106,

107,

108 The diminished expression of E-cadherin correlates to poor prognosis,

109 but a Cox multivariate analysis revealed that the expression of dysadherin, which downregulates E-cadherin expression and promotes metastasis, is an independent prognostic factor.

110 Other potential indicators of poor survival include p53 null mutation, endothelin (vasoactive peptide), VEGF, fascin (actine bundling protein), PGP9.5 methylation, Mina53 (a novel Myc target gene), valosin-containing protein (VCP), survivin, and EphA2 (a receptor tyrosine kinases).

86,

111,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116,

117,

118 The reduced expressions of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) receptors, gamma-catenin, mismatch repair gene MLH1, and bcl-2 are also candidates predicting poor survival.

48,

109,

119,

120 However, the majority of these genetic factors are closely associated with pathologic stage. It is unclear, therefore, whether these factors represent independent indicators for prognosis.

Failure and causes of death. These can be divided into perioperative death within 30 days of resection and death related to the tumor growth such as local recurrence and distant metastasis. An increased risk of the perioperative death includes increasing age at diagnosis, increasing tumor size and depth of invasion, and impaired preoperative respiratory function.

72,

84 Apart from progression of the tumor, pulmonary complications and anastomotic failure are the leading causes of perioperative death; these account for about 50% and 10% of deaths, respectively.

3,

121 The pulmonary complications, which are also the most common causes of morbidity, consist of pneumonia, atelectasis, adult respiratory distress syndrome, pleural effusion, tracheal fistula, and chylothorax.

3 The perioperative mortality has decreased dramatically; it was on the order of 10% ± 5% in the past but is now 1.2% to 6% in many recent reports.

2,

4,

7,

10,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

121 This improvement might be due to exclusion of high-risk patients from surgical resection,

70 induction of preoperative chemoradiotherapy, or both.

2 The latter reason may be controversial as there are conflicting results suggesting that hospital mortality is higher in patients with chemoradiotherapy and surgery than in those undergoing surgery alone.

122 On the other hand, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed that preoperative chemoradiotherapy does not increase treatment-related mortality.

5

Metastases to other organs, particularly liver, lung, and bone occur in 25% to 30% of patients within the first 3 years, and 40% to 45% of patients develop nodal metastases in the superior mediastinum, supraclavicular fossa, or cervical lymph nodes within 5 years. Between 5 and 10 years, 30% of all deaths are due to late recurrence of tumor. At autopsy, local recurrence is prominent in 50% to 75% of patients,

with direct invasion into every conceivable adjacent structure, particularly the trachea and bronchus in about 40%, tracheoesophageal fistula being the cause of death in 10% to15%. Nodal deposits are common; the mediastinal and cervical nodes are positive in about half and the intra-abdominal nodes in a quarter of the patients. Haematogenous dissemination is also common and is present in about half of the patients, affecting the lung in 25% to 30%, the liver in 20%, the bone in 10% to15%, and the adrenal, thyroid, and other organs in 10% or less.

67,

123 Bronchopneumonia is the most common immediate cause of death and is associated with tracheoesophageal or bronchoesophageal fistulae in a high proportion of cases.

67 In rare cases aortoesophageal fistula may form leading to torrential upper GI hemorrhage and death from exsanguination.