Planning Your Abdominal Training Programme

We have seen a great many exercises in this book. All are designed in some way to improve core stability, develop the condition of your abdominal muscles, and enhance the function of your trunk area. Some are basic, some more advanced. Many are used in combination with stretching or strength training, for example, to achieve core stability as part of an overall training plan. Some are worked in conjunction with postural correction. How do we put it all together to form a coherent abdominal training programme?

Your current abdominal muscle condition

Before we start to plan an abdominal training programme we must determine the current state of your abdominal muscles. To do this, we use four basic exercises as simple tests. These are designed to show not how good or bad your muscles are in terms of tone or strength, but to give you a point at which to start – your baseline abdominal condition.

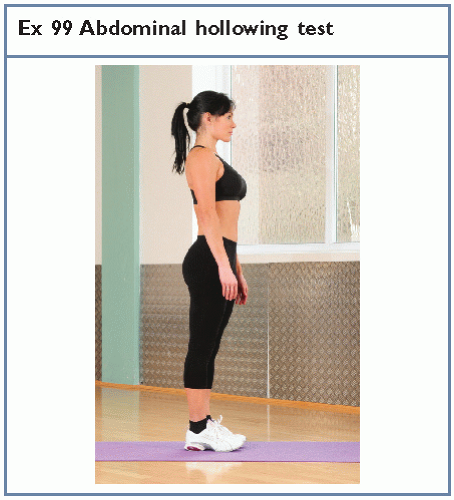

The first exercise is abdominal hollowing, as used in exercise 18 (page 95) but with some modifications. It measures your ability firstly to perform an important muscle isolation, and secondly to hold the position – a test of muscle endurance.

Starting position

Stand with your back flat against a wall and your feet forwards of the wall by 20 cm. You can place your thumbs inside the waistband of your trousers/shorts so that there is a small (1 cm) gap between your abdominal wall and the waistband.

Action

Focus your attention on your lower abdominal region. Breathe in and, as you breathe out, try to draw your abdominal wall away from your waistband. Hold this position for 10 seconds while breathing in and out normally.

Points to note

It is possible to get a false result on this test by drawing your abdominal wall in through simply taking a very big breath and lifting your ribcage. Make sure you breathe normally and keep your ribcage still through the exercise.

Training tip

If you find you are unable to hold the hollow position for 10 seconds, use the test as an exercise. Initially focus on holding for 1-2 seconds and build up the holding time. When you can hold for 10 seconds you have passed the test.

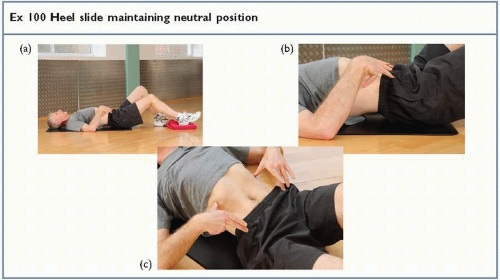

The next test measures your ability to use your core stabilising muscles to maintain the position of your spine as you move another part of your body. This is a vital function of the abdominals – to protect the spine and keep the correct alignment against forces acting on it. It is a modification of exercise 23.

Starting position

Begin lying on the floor on a mat, with your knees bent and feet flat. Place your fingers lightly on the bones at the front of your pelvis (anterior superior iliac spines).

Action

Straighten your right leg, sliding the heel out over the floor. At the same time, use your fingers to monitor pelvic movement. The aim of the test is for you to be able to straighten firstly your right leg and then the left, without the pelvis moving.

Points to note

If you are very unstable in the lumbar spine, the pelvic movement is obvious. Your pelvis will tip forwards and the pelvic bones beneath your fingers will move downwards. As this happens your spine will hollow, increasing the gap between your back and the mat (b).

Training tip

If you are unable to hold the spine still, the test is failed. Practise exercise 15 (page 92) for 2-3 days until you are able to master the movement. Then use exercise 23 (page 103) and finally exercise 28 (page 108) until you are able to pass the test.

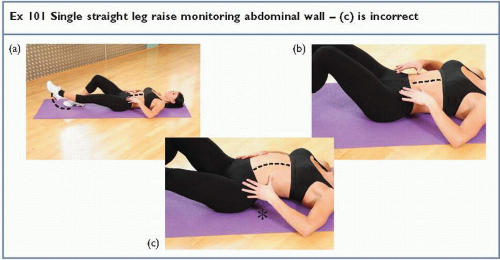

Note: The third test measures your ability to tighten your abdominal muscles and draw them in flat. We saw in chapter 2 that the transversus abdominis muscle draws the abdominal wall in while the rectus abdominis and external oblique move the spine and produce powerful actions. In chapter 17 research was highlighted which showed that the deep stabilisers should contract slightly before the superficial muscles to ‘set’ the abdomen before any movement occurs. This test is a measure of the setting function, using a modification of exercise 29 (page 109).

Starting position

Begin lying on the floor on a mat, with your legs straight. Spread your fingertips and place them about 1 cm above your abdomen.

Action

Raise and lower your right leg and then your left three times, each by 15-20 cm (a). At the same time pay attention to the contour of your abdominal wall; it should stay flat, so that it remains below your fingertips (b). If your abdominal wall bulges so that it touches your fingers, you have failed the test (c).

Points to note

This movement can be very subtle. If you find it difficult to monitor your abdominal wall, work with a partner. They can simply watch your abdomen to see if it bulges (fail) or stays flat (pass) as you lift your legs.

Training tip

If you fail this test, it means you have either weak core stabilisers, or a muscle imbalance where you surface abdominals are stronger than your deep stabilisers, particularly the transversus muscle. Practise exercise 15 (page 92) for 2-3 days until you are able to master the movement. Then use exercise 23 (page 103) for 2-3 days before retesting yourself.

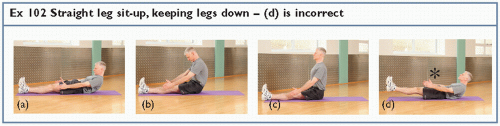

Note: The fourth test should only be attempted if you have passed tests 1-3, and if you have no history of back injury. It is a measure of both abdominal muscle strength, and your ability to shorten you rectus abdominis muscle enough to bend (flex) your spine to curl up rather than sit up straight. It is a monitored version of exercise 63 (page 145).

Starting position

Begin lying on the floor on a mat, with your legs straight and arms by your sides.

Action

Firstly bend your neck (drawing your chin inwards) to look at your feet (a). Tighten your abdominal muscles and flatten your back onto the mat and then curl (bend) your trunk (b) to sit up (c). Stop the exercise immediately if your legs begin to lift from the mat; when they lift, you have failed the test (d).

Points to note

This is a hard test for highly trained athletes who want to measure their abdominal performance. It must be performed slowly and stopped immediately if the legs lift. To continue the movement with the legs lifting or to perform the exercise quickly places an excessive stress on the lumbar spine. Some individuals naturally find this exercise difficult if they are heavy in the upper body and have lighter legs. Their body proportions are such that they cannot easily reduce the leverage action of the trunk sufficiently to perform the exercise correctly.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree