Fig. 15.1

(a–e) CT scan pre- and post-contrast showing a small tumour (x) before injection (a), in arterial time (b, c) and venous time (d, e) (Courtesy of S. Novellas, Radiology, Arnault-Tzanck Institute, Saint-Laurent-du-Var and CHU Nice, Nice, France)

(a)

Solid mass: This lesion contains little or no fluid component; hence, the fluid attenuation is <20 HU. It consists of predominantly enhancing tissue. A change in attenuation of ≥15 HU is considered as enhancement and is characteristic of RCC. One should bear in mind that renal tumour do not enhance as much as the normal renal parenchyma, especially in the nephrographic phase [3]. Avid enhancement (140 HU), presence of necrosis and heterogeneity are more in favour of clear cell pathology than of chromophobe and papillary variants which are less vascular and homogenously enhancing.

(b)

Tumour size: Many small renal masses are benign, and CT cannot accurately differentiate them. Here the size is used as “an indicator” of the likelihood of malignancy. Among renal masses <1 cm, 46 % are benign. In 1–2 cm tumours, 20–22 % are benign. When size is more than 4 cm, only <10 % turn out to be benign. There is an increase in likelihood of malignancy by 16 % per cm of diameter [4, 5]. Obviously ruling out or confirming a renal tumour cannot be based solely on the initial lesion size. Therefore, when surveillance criteria apply (see later), a regular follow-up of such small lesions is necessary to detect if they are rapidly growing, i.e. more likely to be malignant and high-grade tumours, or very slowly or non-growing and mostly consistent with benign or low-grade tumours.

(c)

Evidence of fat in the mass suggests angiomyolipoma (AML). An area within the tumour of more than 20 pixels with an attenuation of <−20 HU or >5 pixels with attenuation <−30 HU is indicative of fat and consistent with the diagnosis of AML.

(d)

Oncocytoma is another benign renal tumour. It shows a characteristic central stellate scar in one third of cases (Fig. 15.2). Segmental enhancement inversion in the corticomedullary phase and early excretory phase may help to distinguish RCC from oncocytoma with 80 % sensitivity and 99 % specificity.

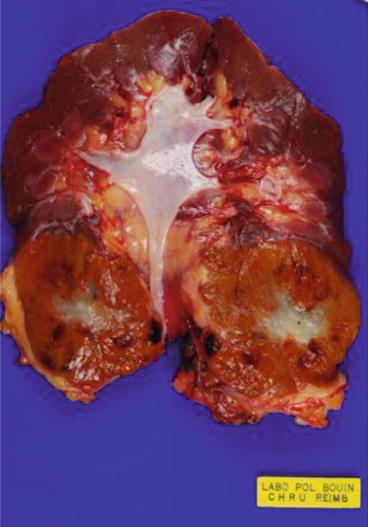

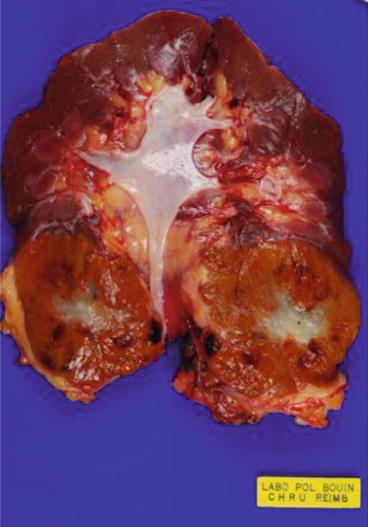

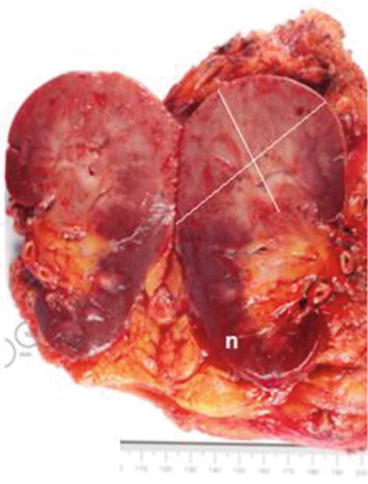

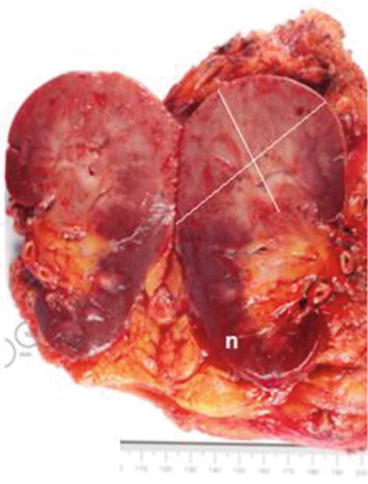

Fig. 15.2

Features of an oncocytoma. See the characteristic central stellate whitish scar (Courtesy of A. Durlach, Pol Bouin Laboratory, University Hospital of Reims, France)

(e)

Metanephric adenoma is a benign tumour indistinguishable by CT scan from RCC. It is a solitary lesion with poor vascularity similar to PRCC and may contain fine calcific foci. These lesions are treated by surgery and only histopathological studies will allow their diagnosis.

(f)

Calcifications within a solid tumour are also frequently encountered.

(g)

Perirenal fat invasion (IIIa) detected in CT scan has 98 % positive predictive value. However, the sensitivity of CT is low here since it predicts only 46 % of cases. MDCT is superior in the detection of renal vein and IVC thrombus (IIIb and IIIc).

(h)

CT scan can predict the need for adrenalectomy during nephrectomy when there is direct invasion into the adrenal gland, tumours larger than 7 cm in the upper pole, multifocal tumours or IVC tumours.

(i)

Number and size of loco-regional lymph nodes and the need for lymphadenectomy are also evaluated in preoperative CT [6].

(j)

Angiographic CT and 3D reconstruction are helpful in planning for nephron-sparing surgery by evaluating the tumour and vascular anatomy.

15.3.3 MRI

MRI is indicated when CT scan is inconclusive, in patients in whom iodinated contrast medium is contraindicated, or when more evaluation of a tumour thrombus is needed. It also avoids the hazard of ionising radiation (Fig. 15.3a–d).

Fig. 15.3

(a–d) MRI showing a cystic renal carcinoma: (a) T2-weighted, (b) T1-weighted without gadolinium, (c, d) T1-weighted with gadolinium (Courtesy of S. Novellas, Radiology, Arnault-Tzanck Institute, Saint-Laurent-du-Var and CHU Nice, Nice, France)

It is important to note that gadolinium is not always safe. It is known to cause nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients with GFR below 30 ml/min, particularly those on dialysis, post renal transplant and with acute renal failure. The nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is consistent with abnormal proliferation of fibroblasts in skin, muscles, liver, lungs and heart leading to organ dysfunctions, immobility and contractures. Strategies to overcome these complications include using low dosage, early post-MRI dialysis and avoidance of the agent during acute renal failure [7].

(a)

Solid renal masses are isointense or moderately hypointense in T1-weighted images and hyperintense in T2-weighted images. Papillary RCC is hypointense in T2-weighted image. Gadolinium is used to study the degree of enhancement which is less than 5 % in renal cysts and at least 97 % in solid masses. The degree of enhancement is often useful in subtyping, as the percentage of signal intensity change in clear cell carcinoma is significantly higher than in papillary carcinoma with chromophobe carcinoma falling intermediate [8, 9].

(b)

Macroscopic fat is well detected by MRI which suggests AML. The presence of microscopic fat is also seen in both clear cell RCC and papillary RCC.

(c)

The urologist should be aware of the MRI protocol sequences used for evaluating the renal tumour [12].

T2HASTE (half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin echo): It is done in coronal and axial planes and rapidly acquired. It provides good anatomy and overview. Fluid-containing structures appear bright.

T1-gradient echo: Fat is bright and AML and myelolipomas are conspicuous. Complex fluid (e.g. haemorrhage) is also bright. Adenopathy is easily visualised.

T1-gradient echo with fat saturation: Fat-containing structures become dark; complex fluid remains bright.

T1-gradient echo 3D dynamic sequence after IV gadolinium: Enhancement within any portions of a mass or cyst is consistent with a neoplasm. Vessels also enhance.

MR angiography and MR venography: Vessels enhance allowing for detection of renal vein and IVC involvement. Vascular anatomy can be mapped.

CT/MRI angiography is useful in selected cases to obtain information about renal vascular anatomy especially when planning for selective vessel clamping in partial nephrectomy. CTA is more accurate than MRA in detecting supernumerary vessels.

15.3.4 PET Scan

PET scan is not recommended as a standard investigation either in initial diagnosis, initial staging or follow-up of RCC. There is no advantage of PET scan over CT scan in the characterisation and initial staging. The reported sensitivity of PET in detecting primary RCC is far less (47–60 %) compared to CT (92–97 %) with comparable specificity (100 % for both) and accuracy [13, 14].

PET scan can have a role in restaging of metastatic RCC (mRCC) and is useful in characterising an anatomical lesion of unknown significance [15]. PET scan is helpful for clarifying findings on other imaging modalities suggestive of metastatic disease, bilateral disease or recurrence, particularly in settings where a positive PET will avoid an invasive biopsy. PET may be appropriate if there is suspicion of a metastatic lesion and biopsy of that lesion is considered potentially less invasive than biopsy of the kidney or performing nephrectomy. The overall PET scan sensitivity for detection of metastatic RCC lesions is inferior being 75 % in lung metastasis, 78 % in bone lesions, 64 % in soft tissue lesions and 75 % in retroperitoneal lymph nodes. In no case has PET scan detected a metastasis that had not been visualised in CT or MRI. However, the overall specificity is higher than any other tests [16, 17].

15.3.5 Categorisation of Renal Cysts

Classically ultrasound is the diagnostic tool for a simple renal cyst. Rounded, well-demarcated lesion with regular sharp borders, imperceptible wall, anechoic content and strong posterior sonic/acoustic enhancement are the features of a simple renal cyst and do not need further studies, namely, CT or MRI.

The presence of varying degrees of complexity in a cystic lesion, like internal echoes, septa, thickness of wall, calcification and mural nodularity, requires further evaluation with CT scan (Fig. 15.4a, b). Based on the CT findings, Morton Bosniak classified cystic lesions into four classes in 1986 [18] and added class 2 F later on (Table 15.1).

Fig. 15.4

(a, b) A Bosniak IV left renal cyst seen on CT scan (horizontal and sagittal plans). It was proven to be a clear cell carcinoma (Courtesy of S. Novellas, Radiology, Arnault-Tzanck Institute, Saint-Laurent-du-Var and CHU Nice, Nice, France)

Table 15.1

The Bosniak classification of renal cystic disease

Category | Features | Malignant risk | Management | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Category I | Simple renal cyst | Round or oval shape, anechoic posterior enhancement (through transmission), thin, smooth wall Homogeneous water content, sharp delineation with the renal parenchyma, no calcification, no enhancement or wall thickening | Less than 1 % | No follow-up needed |

Category II | Minimally complicated cyst | Cystic lesion with some abnormal radiological features <1 mm septations (hairline thin) Fine calcifications within the septum or wall <3 cm in diameter Hyperdense cysts (>20 Hounsfield units) | Less than 3 % | No follow-up needed |

Category IIF | Complicated cyst for follow-up | Cystic lesion with increased abnormal findings, multiple thin septum Septa thicker than hairline or slightly thick wall calcification, which may be thick intrarenal, >3 cm No contrast enhancement | 5–10 % | Follow-up recommended |

Category III | Indeterminate | More complicated uniform wall thickening/nodularity Thick/irregular calcification Thick septa Enhances with contrast | 50 % | Surgery recommended |

Category IV | Malignant | Large cystic components Irregular margins/prominent nodules Solid enhancing elements, independent of septa | 75–90 % | Surgery recommended |

Bosniak category I and II renal cysts do not require further imaging or follow-up as the malignancy risk is low. Patients in category IIF, because of the approximate 5 % malignant risk, do require periodic imaging. For category III (50 % malignant risk) and category IV (75–90 % malignant risk), surgical excision is recommended. Although MRI may add further information, it should be used as an adjunct to CT scans in difficult cases [19, 20].

15.3.6 Renal Tumour Biopsy

Percutaneous needle biopsy of the renal mass was traditionally limited by concerns about its safety, accuracy and sampling errors. Biopsy was reserved for patients suspected of having unresectable or disseminated RCC, renal metastasis, renal abscess or lymphoma [21] (Fig. 15.5). With improvement in diagnostic accuracy of biopsy, refinements in image guiding and better understanding of small renal masses, the indications for tumour biopsy have changed. The increasing incidence in the diagnosis of incidental small renal masses (SRMs), the development of conservative and minimally invasive treatments for low-risk RCCs and the discovery of novel targeted treatments for metastatic disease are now leading to wider indications for renal tumour biopsy [22].

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree