Peptic Ulcer Disease

The term peptic ulcer disease (PUD) refers to disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract caused by the action of acid and pepsin. These agents not only cause injury themselves, but also typically augment the injury initiated by other agents. The spectrum of peptic ulcer disease is broad, including undetectable mucosal injury, erythema, erosions, and frank ulceration. The correlation of severity of symptoms to objective evidence of disease is poor. Some patients with pain suggesting peptic ulcer disease have no diagnostic evidence of mucosal injury, whereas some patients with large ulcers are asymptomatic.

I. PATHOGENESIS.

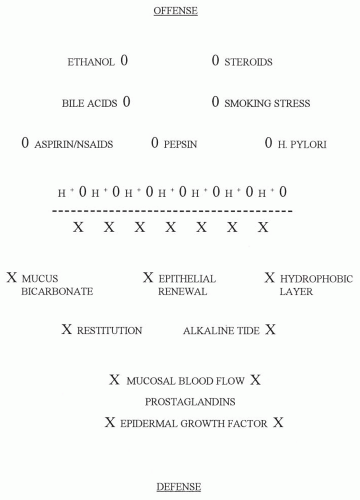

Gastroduodenal mucosal injury results from an imbalance between the factors that damage the mucosa and those that protect it (Fig. 24-1). Therefore, injurious factors may predominate and cause injury not only when they are excessive, but also when the protective mechanisms fail. Although we have learned much in recent years about the mechanisms of injury and protection of the mucosa of the upper gastrointestinal tract, we still have an imperfect understanding of why discrete ulcers develop and why peptic disease develops in one person and not in another.

A. Injurious factors.

The mucosa of the upper gastrointestinal tract is susceptible to injury from a variety of agents and conditions. Endogenous agents include acid, pepsin, bile acids, and other small-intestinal contents. Exogenous agents include ethanol, aspirin, other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and Helicobacter pylori infection.

Acid appears to be essential for benign peptic injury to occur. A pH of 1 to 2 maximizes the activity of pepsin. Furthermore, mucosal injury from aspirin, other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, and bile acids is augmented in the presence of acid. On the other hand, ethanol causes mucosal injury with or without acid. Corticosteroids, smoking, and psychological and physiologic stress appear to predispose or to exacerbate to mucosal injury in some people by mechanisms that are incompletely understood.

B. Protective factors.

A number of mechanisms work together to protect the mucosa from injury (Table 24-1).

1. Concepts

a. Gastric mucosal barrier. In the early 1960s, Horace Davenport identified the so-called gastric mucosal barrier, which describes the ability of the gastric mucosa to resist the back diffusion of hydrogen (H+) ions and thus to contain a high concentration of hydrochloric acid within the gastric lumen. When the barrier is broken by an injurious agent, such as aspirin, H+ diffuses rapidly back into the mucosa, which results in mucosal injury.

b. Cytoprotection. More recently, the concept of cytoprotection has been developed to explain further the ability of the mucosa to protect itself. The term cytoprotection is somewhat of a misnomer in that it does not refer to the protection of individual cells but rather to protection of the deeper layers of the mucosa against injury. The classic experiments of Andre Robert illustrate the phenomenon of cytoprotection. When he introduced 100% ethanol into the stomachs of rats, large hemorrhagic erosions developed. However, when he first instilled 20% ethanol, a concentration by itself that did not cause gross injury, and subsequently administered 100% ethanol, no hemorrhagic erosions developed. Clearly, some endogenous protective mechanism had been elicited by the preliminary exposure to a low concentration of the injurious agent. This protective effect was abolished by pretreatment with indomethacin at the time of instillation of 20% ethanol. Because indomethacin is a potent inhibitor of prostaglandin synthesis, this observation suggested that cytoprotection was mediated by endogenous prostaglandins. In fact, application of exogenous prostaglandins has been shown to protect the gastric mucosa. Prostaglandins do inhibit gastric acid secretion, but their cytoprotective effects can be demonstrated at doses below those necessary to inhibit acid.

Figure 24-1. Diagram of factors that promote mucosal injury (Offense) versus those that protect the mucosa (Defense). On the offensive side, hydrochloric acid (H+) is essential for the action of pepsin and many ulcerogenic factors. For example, aspirin, bile acids, and the nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs cause much more mucosal injury in an acid milieu. The roles of corticosteroids, smoking, and stress are less clear, but these factors probably contribute to mucosal injury. Alcohol can cause mucosal injury without the assistance of acid. The defense of the mucosa is a complex phenomenon that involves the interaction of a number of protective mechanisms indicated in the figure. (See Table 24-1 and text.) |

2. Mediators of mucosal protection

a. Mucus is secreted by surface epithelial cells. It forms a gel that covers the mucosal surface and physically protects the mucosa from abrasion. It also resists the passage of large molecules, such as pepsin; however, H+, other small particles, and ethanol seem to have little difficulty in penetrating mucus to reach the mucosal surface.

TABLE 24-1 Gastroduodenal Mucosal Protective Factors | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

b. Bicarbonate is produced in small amounts by surface epithelial cells and diffuses up from the mucosa to accumulate beneath the mucous layer, creating a thin (several micrometers) layer of alkalinity between the mucus and the epithelial surface.

c. The hydrophobic layer of phospholipid that coats the luminal membrane of surface epithelial cells is believed to help prevent the back diffusion of hydrophilic agents such as hydrochloric acid.

d. Mucosal blood flow is important not only in maintaining oxygenation and a supply of nutrients, but also as a means of disposing of absorbed acid and noxious agents.

e. The alkaline tide refers to the mild alkalinization of the blood and mucosa that result from the secretion of a molecule of bicarbonate (HCO3−) by the parietal cell into the adjacent mucosa for every H+ ion that is secreted into the gastric lumen. This slight alkalinity may contribute to the neutralization of acid that diffuses back into the mucosa and may augment the effects of mucosal blood flow.

f. Epithelial renewal, which involves the proliferation of new cells and subsequent differentiation and migration to replace old cells, but which requires several days, is necessary in the healing of deeper lesions, such as erosions and ulcers.

g. Restitution refers to the phenomenon of rapid migration, within minutes, of cells deep within the mucosa to cover a denuded surface epithelium. This process probably accounts for the rapid healing of small areas of superficial injury.

h. Prostaglandins, particularly of the E and I series, are synthesized abundantly in the mucosa of the stomach and duodenum. They are known to stimulate secretion of both mucus and bicarbonate and to maintain mucosal blood flow. Prostaglandins also may have beneficial protective effects directly on epithelial cells.

i. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) is secreted in saliva and by the duodenal mucosa and may exert topical protective effects on the gastroduodenal mucosa.

C. Relation of Helicobacter pylori to peptic disease.

Since 1983, evidence has accumulated to implicate a bacterium, H. pylori, in the pathogenesis of some forms of peptic disease. The organism is found adherent to the gastric mucosal surface and, when looked for, has been identified in more than 90% of patients with duodenal ulcer. Its presence has also been correlated with gastritis, gastric ulcer, and gastric erosions and with chronic infection, gastric mucosal atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and in a minority of patients, gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma. Some patients with H. pylori are asymptomatic and may even have

normal-appearing gastric mucosa by endoscopy, but identification of the organism is associated with histologic gastritis in nearly 100% of patients.

normal-appearing gastric mucosa by endoscopy, but identification of the organism is associated with histologic gastritis in nearly 100% of patients.

1.

The mechanisms by which H. pylori are involved in the pathogenesis of peptic conditions are unclear. H. pylori produce ammonia and elaborate other toxins that may directly damage the mucosa and initiate an inflammatory response. The organism can be treated by bismuth-containing compounds (e.g., bismuth subsalicylate [Pepto-Bismol]), PPI, and some antibiotics, which appear to facilitate the treatment of the associated peptic condition. For example, patients with H. pylori-associated duodenal ulcer have a longer period of remission when they receive treatment for both the ulcer and the organism than when they are treated for the ulcer alone.

2. Treatment.

Several studies have shown that duodenal ulcers may be curable by eradication of H. pylori with so-called triple therapy (e.g., bismuth subsalicylate q.i.d., tetracycline (or ampicillin) 500 mg q.i.d., and metronidazole 250 mg q.i.d. for 2 weeks, plus omeprazole (Prilosec) 20 mg b.i.d. until healing. Other studies have shown eradication rates higher than 90% with omeprazole (Prilosec) 40 mg b.i.d. or lansoprazole (Prevacid) 30 mg b.i.d. or Pantoprazole 40 mg q.d. or Esomeprazole 40 mg q.d., or Rabeprazole 20 mg b.i.d., plus amoxicllin 1 g b.i.d. and clarithromycin (Biaxin) 500 mg b.i.d. for 7 to 14 days. In penicillin-allergic patients, metronidazole (Flagyl) 500 mg b.i.d. may be used instead of Amoxicillin. H. pylori eradication clearly reduces peptic ulcer recurrence rates and is recommended for all patients with peptic ulcer disease who are infected with H. pylori.

D. Relation of aspirin and other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs to peptic disease.

Aspirin and other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) cause mucosal injury and ulceration throughout the entire gastrointestinal tract, especially in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. The mechanisms of injury are multifactorial and include both direct mucosal injury and inhibition of prostaglandins that are protective to the mucosa. The risk for mucosal damage related to aspirin and NSAID ingestion is related to a previous history of peptic ulcer disease, high and frequent doses of the drugs, and concomitant use of corticosteroids or use of more than one NSAID. The mucosal injury may be diffuse, and ulcers may be multiple. Patients may be asymptomatic or may have frank bleeding, anemia, or strictures. There is some clinical evidence that the gastric infection, H. pylori, may contribute to enhance mucosal damage from NSAIDs. Treatment is to discontinue the offending agents and, if necessary, begin histamine-2 (H2) blocker or PPI therapy. If NSAID treatment must be continued, therapy with the synthetic prostaglandin E1 derivative, misoprostol 100 to 200 µg q.i.d. or a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) (e.g., omeprazole 20-40 mg daily) has been shown to heal the mucosal lesions. Prostaglandins are produced in the gastric mucosa by the progressive enzymatic action of cycloxygeranase I and II (COX) on arachidonic acid released from membrane phospholipids. NSAIDS inhibit COX I and COX II enzymes. Specific COX II inhibitors have been developed to allow the selective inhibition of those prostaglandins that are proinflammatory (e.g., in the joints). COX II inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib [Celebrex]) inhibit prostaglandins that are effective in gastroduodenal mucosal protection to a much lesser degree, and thus are thought to be safer to use in patients with history of peptic ulcer disease.

II. COMPLICATIONS OF PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE

A. Bleeding/hemorrhage.

It is estimated that PUD is responsible for greater than 50% of all cases of UGI tract hemorrhage. Ulcers may erode into blood vessels and may result in life-threatening hemorrhage. If bleeding is slower or intermittent, iron-deficiency anemia may result. Some patients may also present with occult GI bleeding.

1. Patients with brisk bleeding from PUD

usually present with hematemesis, melena, and/or with hematochezia with clots and hypotension.

2. Risk factors for bleeding from PUD

include ingestion of aspirin, NSAIDS, platelet inhibitory drugs, coagulopathy, older age, and the presence of H. pylori infection.

B. Perforation.

Duodenal or gastric ulcers may perforate into the peritoneal cavity. In 10% of patients, perforation is accompanied by hemorrhage. Initially, patients feel an abrupt onset of intense abdominal pain which is then followed by hypotension and shock as the peritoneal cavity is flooded by gastric juice and contents and peritonitis develops. Mortality is imminent if appropriate therapy is not initiated immediately.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree